Nestled beneath the jagged desert terrain of the Karkas Mountains sits the crown jewel of Iran’s nuclear program. Natanz facility, home to the Islamic Republic’s largest known uranium enrichment center, enjoyed renewed national praise when President Hassan Rouhani visited the site Saturday to mark the country’s 16th annual National Nuclear Day. As envoys from the United States, Iran, and mediatory countries prepared for the upcoming week’s negotiations in Vienna—aimed at curbing Tehran’s atomic ambitions—Rouhani christened an army of advanced IR-6 centrifuges capable of yielding “10 times more product” in celebration of the holiday.

The next day, an explosion of unknown origins brought down the enrichment site’s primary and backup electrical grids. Among the blast’s casualties were “several thousand centrifuges” but no civilians.

Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization spokesperson, Behrouz Kamalvandi, initially attributed the loss of power to an “accident,” but later reporting out of Israel and Iran pointed to sabotage by Jerusalem. By Tuesday, a several high-profile Iranian officials—including Rouhani, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, and nuclear chief Ali Akbar Salehi—had assigned blame for the “nuclear terrorism” to their “Zionist” rivals in a government-wide call for retaliation.

“A large portion of the enemy’s sabotage can be restored, and this train cannot be stopped,” Salehi insisted after the infiltration. Iran’s state media adopted a similar narrative, reporting the impact to be minimal and concentrated to the plant’s antiquated IR-1 centrifuges.

While the full extent of the damage to Iran’s nuclear program remains unknown, Israeli and American intel leaked to Israel-based outlets and the New York Times paints a different picture. The power outage, reports found, resulted from a large explosion 165 feet underground and beneath more than 20 feet of reinforced concrete. A device was smuggled into the site in advance and detonated remotely, taking out the power supply fueling chains of centrifuges.

Kamalvandi, speaking from his hospital bed after falling 23 feet into a hole caused by the blast, dismissed the incident as a “little explosion” but vowed “revenge on the Zionist regime.” Given the clear and credible attribution to Israeli forces in sources close to the horse’s mouth, some experts fear the Islamic Republic might be cornered into retaliation in the absence of Jerusalem’s plausible deniability. Others point out that in the earliest stages of the Vienna negotiations, such a move would derail Tehran’s efforts to secure desperately needed sanctions relief.

Also in response to the attack—and in a potentially miscalculated diplomatic tactic ahead of this week’s talks—Rouhani announced plans to enrich uranium at 60 percent purity as leverage over his Western counterparts. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which is responsible for overseeing the country’s nuclear program confirmed that Iran has “almost completed preparations” to do so at Natanz.

“If the aim was to limit Iran’s nuclear capability, I have to say that on the contrary, all the centrifuges that went out of order due to the incident were of the IR-1 type, and they are being replaced with more advanced ones,” Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman Saeed Khatibzadeh said Monday.

But blanket promises to restore the nuclear cache to its former glory may be in vain while unresolved breaches cripple Iran’s security apparatus. “Tehran will respond with rhetorical bluster, but it is likely that it has also initiated a frenzied security review to determine which external actors have obtained this access,” Norman Roule, former U.S. national intelligence manager for Iran, told The Dispatch. “Unless they can resolve their security concerns, they cannot be sure they will be able to protect their personnel or sensitive facilities from future attacks.”

The timing by Mossad, Israel’s spy agency and the suspected culprit, was no coincidence. Former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert speculated Wednesday that the explosives were planted at the facility well in advance, “maybe 10 years ago or 15 years ago,” before being triggered remotely.

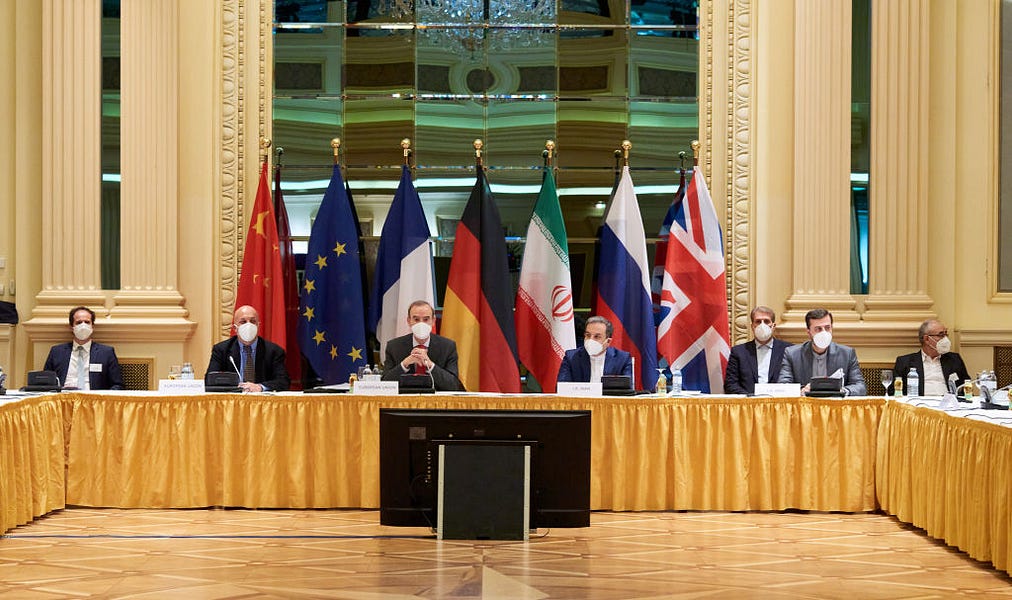

As the U.S. and other vested parties kicked off indirect talks with Iran in an effort to reinstate the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—which in its original iteration was vehemently opposed by Israeli leaders—Jerusalem’s objective was two-fold. “The first is a message from Israel to the United States and the EU three that: ‘We have a vote on the nuclear deal as well and we’re not going to sit idly by while an agreement is negotiated in a European capital that directly affects our security,’” Jason Brodsky, a senior analyst at Iran International, told The Dispatch. “The second message is of course to the Iranians: ‘We’re watching you and we’re not bound by the nuclear deal.’”

Jerusalem’s shadow war with Tehran spans back some four decades, with particular attention paid to Iran’s nuclear and military infrastructure in recent years. Last June and July, a mysterious string of explosions and fires broke out in and around factories across the country, including Natanz’s centrifuge plant. Another strike targeted eastern Tehran’s Khojir missile production complex.

In November 2020, a satellite-controlled machine gun shot and killed Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, a nuclear scientist and brigadier general in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), in a strike widely attributed to the Israelis. The attack was carried out on Iranian soil.

Perhaps the most high-profile of these covert efforts was devised under the Bush administration and implemented under the Obama administration, when the U.S. and Israel teamed up to install the Stuxnet worm in the computer system of Iran’s Bushehr nuclear power plant. The virus permanently destroyed one-fifth of the country’s centrifuges. Beginning in 2006, the two countries also coordinated a series of cyberattacks on Natanz known as Operation Olympic Games.

“It is clear that at least one external actor—and likely more—has an extraordinary ability to monitor Iran’s most sensitive facilities and personnel,” Roule said. “Operations against these targets have involved no civilian casualties and focused on personnel and architecture Iran would use in lethal actions against its neighbors.”

Gen. Mohsen Rezaei, former IRGC commander-in-chief and current secretary of Iran’s expediency council, tweeted that the attack was indicative of a larger “infiltration phenomenon” and called on the government to make security improvements. And although the Biden administration has unequivocally denied involvement or advance knowledge of the operation, Iran typically associates covert action by Israel with its American allies.

“‘Those who live in glass houses should not throw stones’, says an old English proverb, as a warning to arrogantly ignorant idiots whose provocations bring swift self-destruction,” a newspaper backed by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei wrote on its front page. “All fingers point towards the archenemies of Iran and the Iranian people, including those trying to dupe the Islamic Republic again by dangling the bait of ‘indirect’ talks to rejoin the JCPOA.”

Implicating the administration further, at least from the Iranian point-of-view, was U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s visit to Jerusalem at the time of the attack. During a joint press conference Monday with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Austin steered clear of mentioning Iran altogether while Netanyahu pledged to thwart its rival’s “genocidal goal of eliminating Israel” via nuclear weapon.

The weekend’s events reportedly produced political tumult within Tehran, as some politicians urged foreign ministry leadership to pull out of the Vienna talks altogether. But Zarif said Monday that Iran remains undeterred in its quest for sanctions relief, insisting that the “desperate act” improved his envoy’s standing and calling on the Biden administration to “remove all sanctions imposed, re-imposed, or relabeled since the adoption of the JCPOA.”

According to Brodsky, this demand is a “nonstarter,” regardless of the administration. Under the 2015 agreement, the U.S. retains the right to impose sanctions on Iran for a wide array of non-nuclear behavior—including its domestic human rights abuses, regional sponsorship of terrorism, and extensive ballistic missile program.

Some of the non-nuclear sanctions imposed under the Trump administration target the same entities promised relief from nuclear sanctions under the deal, which affords Iran space to deem them illegitimate and request their removal as a condition of the negotiations. But it has been the consensus among American officials, dating back to the Obama administration, that sanctions targeting non-nuclear transgressions are consistent with the text of the agreement.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken said as much during his Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing in January, when asked by Sen. Ted Cruz if it would be in America’s national security interests to lift terrorism sanctions on Iran. “I do not, and I think that there is nothing—as I see it—inconsistent with making sure that we are doing everything possible, including the toughest possible sanctions to deal with Iranian support for terrorism, its own engagement in that, and the nuclear agreement,” Blinken responded.

“Fast forward a couple of months to Vienna: those sanctions are on the table,” Richard Goldberg, senior adviser at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and former member of the U.S. National Security Council, told The Dispatch. “The Biden administration is making an argument that it is still in our national interests to knowingly give money for terrorism if it gets us strict limits on the nuclear program,” he added, pointing to vague language from State Department spokesperson Ned Price and others as evidence that the U.S. is at least considering Tehran’s steep demand in exchange for a better deal.

That tradeoff might be a compelling one, were its underlying facts true. But the JCPOA has an expiration date of 2030, at which point Iran may be on the precipice of weaponization given its current enrichment level, undeclared nuclear activities, and aggressive nuclear research—the last of which began well before the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the agreement in 2018.

On top of that, “parts of the broader architecture surrounding the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action have already expired,” Brodsky explained. The conventional weapons embargo under U.N. Resolution 2231—a Security Council measure tied to the JCPOA and topic frequently dodged during the Biden administration’s press briefings—ended last year.

In a letter to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in May 2020, a bipartisan group of 387 House members called on the administration to extend the ban past its expiration date in October through “robust diplomacy.” President Trump opted instead to trigger snapback, a provision of the Resolution 2231 allowing a participant state to terminate the sunset on the arms embargo in the event of Iranian noncompliance.

When the bid fell through, Trump issued an executive order threatening sanctions on any entities transferring arms—defensive or offensive—to or from the Islamic Republic. Biden has since notified the Security Council of the U.S.’s reversed position on snapback, but the executive order stands. Whether the administration would enforce it remains to be seen, but there still exists overwhelming congressional consensus that some version of the expired embargo is an urgent necessity.

“Tehran’s aggressive regional activity in recent years argues for a long-term and comprehensive arms embargo against Iran. Iran’s regional actions pose a routine and lethal threat to the men, women, and children of the region, which includes citizens of dozens of countries,” Roule explained. “In this sense, Iran has declared war against the world, to include Americans. However, the international community has done little to punish Iran for a campaign that is unique in modern history.”

The second component of the U.N. arms embargo, set to expire in October 2023, bans entities from supplying Iran with the equipment and technology required to develop a nuclear-capable ballistic missile. It also orders Iran to refrain from producing and testing missiles suited to the delivery of nuclear weapons. The United States called for snapback on the grounds that Iran was violating the latter requirement, but the international community diverges in its definitions of “nuclear-capable.” Either way, Tehran’s rapidly expanding arsenal of missiles—nuclear-capable or not—pose a serious threat to surrounding countries.

“Iran’s missile program is the largest and most diverse in the region. The size of this program exceeds Tehran’s defensive requirements and represents a tool of power projections as much as defense. Tehran has also been increasingly bold in its willingness to share this technology with proxies in Yemen, Syria, Lebanon, and perhaps even Iraq,” Roule said. “No country in history has been so aggressive in its violation of international proliferation norms and laws.”

As the primary targets of Tehran’s multifront proxy war, the U.S.’s Gulf state partners have a vested interest in the outcome at Vienna. But they’ve largely been left out of the negotiating process. While Iran’s missile program isn’t a talking point, for example, sanctions relief and cash reparations that could go directly to funding regional terrorism are. “I think that some of it will end up in the hands of the IRGC or other entities, some of which are labeled terrorists,” then-Secretary of State John Kerry conceded of the first deal, which Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and others were critical of from the time of its conception.

Their concerns are now compounded by a recent spike in missile and armed drone attacks aimed at Saudi Arabia by Iranian-backed groups, even as its foreign ministry extends a ceasefire to Yemen’s Houthis. Days after a barrage of rockets were intercepted over Riyadh in January, Biden temporarily halted arms sales to Saudi Arabia. A couple of weeks later, the State Department revoked the Houthis’ designation as a foreign terrorist organization.

“In the wake of the international community’s weak response to Iran’s use of proxies to attack regional countries with missiles and drones, one cannot blame regional capitals if they doubt the U.S. and international community will adopt a tough line against Tehran’s regional aggression or missile programs following any new nuclear deal,” Roule said.

Far from deterring the Islamic Republic’s hostilities in the region, the JCPOA “ushered in the most aggressive escalation of Iranian foreign policy in decades,” the American Enterprise Institute’s Danielle Pletka wrote in a recent story for The Dispatch.

Going into Vienna, the Biden administration’s first priority is to restore the existing deal before following-on with additional negotiations to make it “stronger and longer” to avoid the repetition of past mistakes. But critics argue that their logic is seriously flawed. “Once they have sanctions relief, why would they negotiate further?” Brodsky asked. “Number one, I’ve yet to see any evidence that the administration has a plan as to how that’s going to happen. Number two, why would Iran ever agree to do so in the first place?”

While economic pressure and covert operations alone may not be sufficient to eliminate Iranian proliferation, they certainly up the costs. A May 2019 Washington Post report found that under the Trump administration’s rigid sanctions regime, Iran’s strapped cash flow to Lebanese Hezbollah forced the terrorist organization to fire or furlough large swaths of its fighters. And domestic anxiety over a contracting economy and surging poverty rate—in part the work of sanctions and in part the work of COVID-19—squeezes the ayatollahs on their home turf.

Under the “maximum pressure” campaign, Goldberg argues, “there was an egg timer on how long this regime was going to be able to hold out on whatever terms the American administration put forward. Otherwise it would likely manage its own collapse.”

While the language of “multilateralism” and “diplomacy” is pleasing to Western ears, the United States and allies must remember who’s seated at the other end of the negotiation table. Tehran has long extorted its nuclear program to push for concessions in other arenas, exerting its malign influence across the Middle East and beyond with near-impunity.

To that end, a singular focus on reviving the expiring JCPOA undermines the U.S.’s ability to look beyond the silo of Iran’s nuclear program to create a lasting, bipartisan strategy.

“I think the obsession with this deal among Europeans, and among some in the United States, has really been a detriment to a broader conversation on the Iran challenge,” Brodsky explained.

“The JCPOA is not the end: The end is durable policy for the United States as it relates to Iran. And when I say durable—I mean bipartisan—because as the Trump administration has shown, you cannot bind the United States to an agreement that lacks the support of the totality of a major political party in this country.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.