It is an age-old mantra of American politics that the middle class are uniquely virtuous, and that their interests have a first claim on Washington’s attention. Bill Clinton said that “the country works better with a strong middle class, with real opportunities for poor folks to work their way into it.” Joe Biden declared that “the middle class built this country,” insisting that “When the middle class does well, everybody does well.” And Marco Rubio has claimed that “If we lose the middle class … we will lose one of the things that makes us different and, in my humble opinion, better than any other land that’s ever existed.”

There are, of course, sound electoral reasons for pitching praise at the middle class. A majority of Americans think themselves middle class, so pitches aimed above or below them risk alienating the largest bloc of voters. But it is worth considering seriously whether there might actually be deeper and more principled reasons for tending to the fears and aspirations of the middle class—rather than, say, those of the deserving poor or job-creating rich. Could Clinton, Biden, and Rubio be right—and not just pandering for votes?

No less a timeless authority on political philosophy than Aristotle would, in fact, say that their paeans to the great middle class were spot on.

In Book IV, Chapter 11 of his great work Politics, Aristotle argued that “the best political community is formed by citizens of the middle class.” More specifically, he claimed,“Those states are likely to be well-administered in which the middle class is large, and stronger if possible than the other two classes”—that is, stronger than the rich and the poor.

The rich, who jealously guard their privileges, tended to be arrogant and oppressive. The poor, wholly displeased with their lot, tended to be covetous and subversive. And so in an oligarchy, where the rich rule, the poor were more likely to rise up and undermine the governance of the polity.

A thriving middle class, therefore, comprising as large as possible a majority of the population, is essential to political stability. “A city ought to be composed, as far as possible, of equals and similars,” Aristotle wrote, “and these are generally found in the middle class.” As a body, the middle class had the temperament and capacity to restrain the domineering tendencies of the rich and the reckless passions of the poor. But they needed numbers to do this. And so “where the middle class is large,” he concluded, “there are least likely to be factions and dissensions.”

The American Founding Fathers echoed this thought. Whereas James Madison did not invoke Aristotle, he had certainly read him. In his Federalist No. 10, he identifies the divide between rich and poor as “the most common and durable source of factions.” And it was therefore essential to keep that divide within bounds.

Were the two men right?

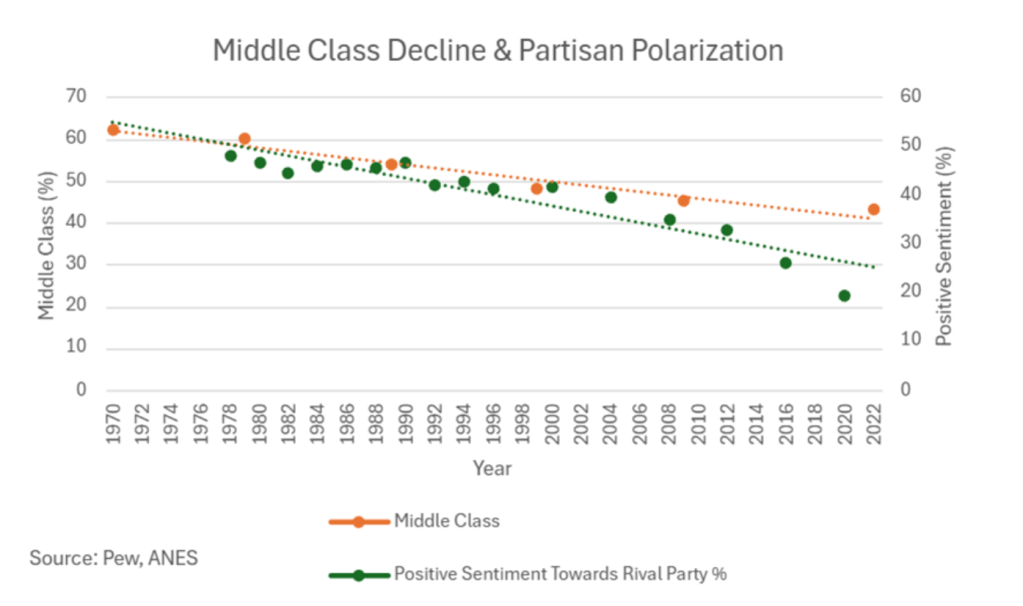

To test Aristotle’s thesis, I plot below, going back to 1970, Pew Research time-series data on the size of the middle class against American National Election Studies data on political polarization. “Middle class” is here defined as living in a household with annual income two-thirds to double the national median (adjusted for household size). Political polarization is measured in terms of the degree of positive feeling toward one’s rival party.

What we find here is a remarkably high degree of correlation between the decline in the percentage of households considered middle class and the rise in political polarization. While the number of data points is not large, and definitions of class and polarization certainly subject to challenge, the exercise would appear strongly to validate Aristotle and Madison. Rising wealth inequality, as defined in terms of middle class shrinkage, gives rise to greater factionalism and, therefore, greater political instability.

The causes of middle class shrinkage are many and varied. They include technological change, globalization of trade and investment, labor market trends, tax policy, increasing education costs, rising housing and health care costs, and changing family structures and demographics. Each interacts with others in complex ways, making the determination of optimal policy fixes tricky. And the debate is perennial over whether we should, as a society, be aiming to maximize the size of the total wealth pie or to focus more on how it is divided.

But we cannot escape the challenge posed by each of the two main political parties treating the other, ever increasingly, as a threat to internal security and traditional values. This bitter and growing division is not amenable to reasoned debate, as each side has solidified myths that do not allow for factual disproof. On the right, there is the charge that America is being destroyed from within by wokeism and the Deep State; on the left, that the culprits are capitalism and racism. If one argues that one or both purported causes are unpersuasive or overwrought, one is labeled either willfully ignorant or complicit. Indeed, “centrism,” as personified by the likes of a Jonathan Haidt or an Andrew Sullivan or a Roland Fryer, has hardened into its own intellectual armed camp.

Aristotle, interestingly, held that “The middle class is best suited to obey reason.” And so if reason no longer governs our political life, perhaps it is because the class most open to it has been quietly shrinking.

To the extent, then, that the republic’s woes owe to the relentless decline of the middle class, what are the cures that don’t worsen the pains of the disease?

We can first say what they are not. They are not a revival of Smoot-Hawley-level tariffs and global trade barriers. Any manufacturing jobs that might be created by raising the price of imports will not resemble the middle-class ones that left 10 or 20 years ago. Automation has seen to that. Even China has lost an eye-popping 7.4 million manufacturing jobs since 2011. Destroying our elite universities, turning away foreign students, deporting farm workers, or setting interest rates by executive order are certainly not helpful either.

But there is some low-hanging fruit in the policy space that would foster growth in the middle class: examples include slashing housing costs through nationwide zoning liberalization, boosting mobility through the repeal of pernicious local licensing, and expanding opportunity by banning non-compete clauses in middle-class occupations. Such reforms have been called “predistributive,” as opposed to redistributive, in that they aim not to compensate for loss but to make the market work better for the non-rich. We should, further, expand support for vocational training in lucrative service professions (like plumbing, carpentry, and HVAC maintenance) and for high-school age local apprenticeships. Not everyone needs a college degree, and certainly not the debt trap that too often comes with it.

The elected class will no doubt keep composing its hymns to the blessed middle class. But if we let it continue to shrink, we will dissolve the glue that’s helped bond the republic for a quarter-millennium.

Editor’s Note, August 1: A previous version of the illustration accompanying this article incorrectly showed Plato instead of Aristotle.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.