Recently, liberal Democratic candidate Kamala Harris received an enthusiastic endorsement from someone very far from her ideologically: former Rep. Liz Cheney. “We may disagree on some things,” said Cheney, “but we are bound together by the one thing that matters to us as Americans more than any other. And that’s our duty to our Constitution and our belief in the miracle and the blessing of this incredible nation.” The support from Cheney (and her father) were not the only surprise support in this cycle—Donald Trump has been receiving increasing support from black and Latino men, as well as Muslim voters in Michigan.

Which all raises the key question: Are we seeing something like a “realignment”? What would that mean, and does it indicate major changes in the electorate coming soon?

Although the concept of a “realignment” is important in American politics, it’s also controversial and contested. A realignment occurs when the parties substantially change their issue priorities, or when blocs of voters switch their loyalty from one party to another. Importantly, a realignment refers to much more than a good election year for a party. The Reagan landslide of 1984 and the Democratic takeover of Congress in 2018 were both consequential, but they did not constitute realignments. They did not fundamentally change the makeup of the two major parties or what those parties stood for.

A seismic exception to a steady trend.

If you’re looking for an actual realignment, the middle of the 19th century is a good place to start. The U.S. had two major political parties in the early 1850s: the Democrats and the Whigs. Though the existing parties were largely polarized on economic issues, they were notably not polarized over the institution of slavery. Both parties had a substantial presence in the North and South, and counted considerable numbers of pro- and anti-slavery voters among their ranks.

But as slavery became more and more central to national politics throughout the ensuing decade, the parties quickly realigned. Democrats emerged as decidedly pro-slavery, while the Whigs were unable to fully pivot to becoming an anti-slavery party. That ultimately proved the party’s demise, as most of its Northern supporters joined the newly formed Republican Party. By 1860, all the Republican electoral strength was located in the North and West, while Democrats solidly won the South.

That election of 1860 is a pretty clear example of a realignment—the emergence of a salient issue in the 1850s triggered shifts that would guide U.S. politics for decades to come—but such elections are exceedingly rare.

Even consequential elections do not necessarily result in such a sudden and stark realignment. The election of 1896, for example, established the Republicans as the party of northeastern industry and the Democrats as the party of the agrarian South and West. A few decades later, the election of 1932 established the New Deal coalition that would guide Democratic policy leadership throughout the mid-20th century. These realigning elections certainly mattered at the time, but as political scientist David Mayhew argued in his thorough book on the topic, these elections also illustrate an important fact about parties and realignments in U.S. history: Their story is not one of occasional seismic shifts, but rather of mostly gradual change.

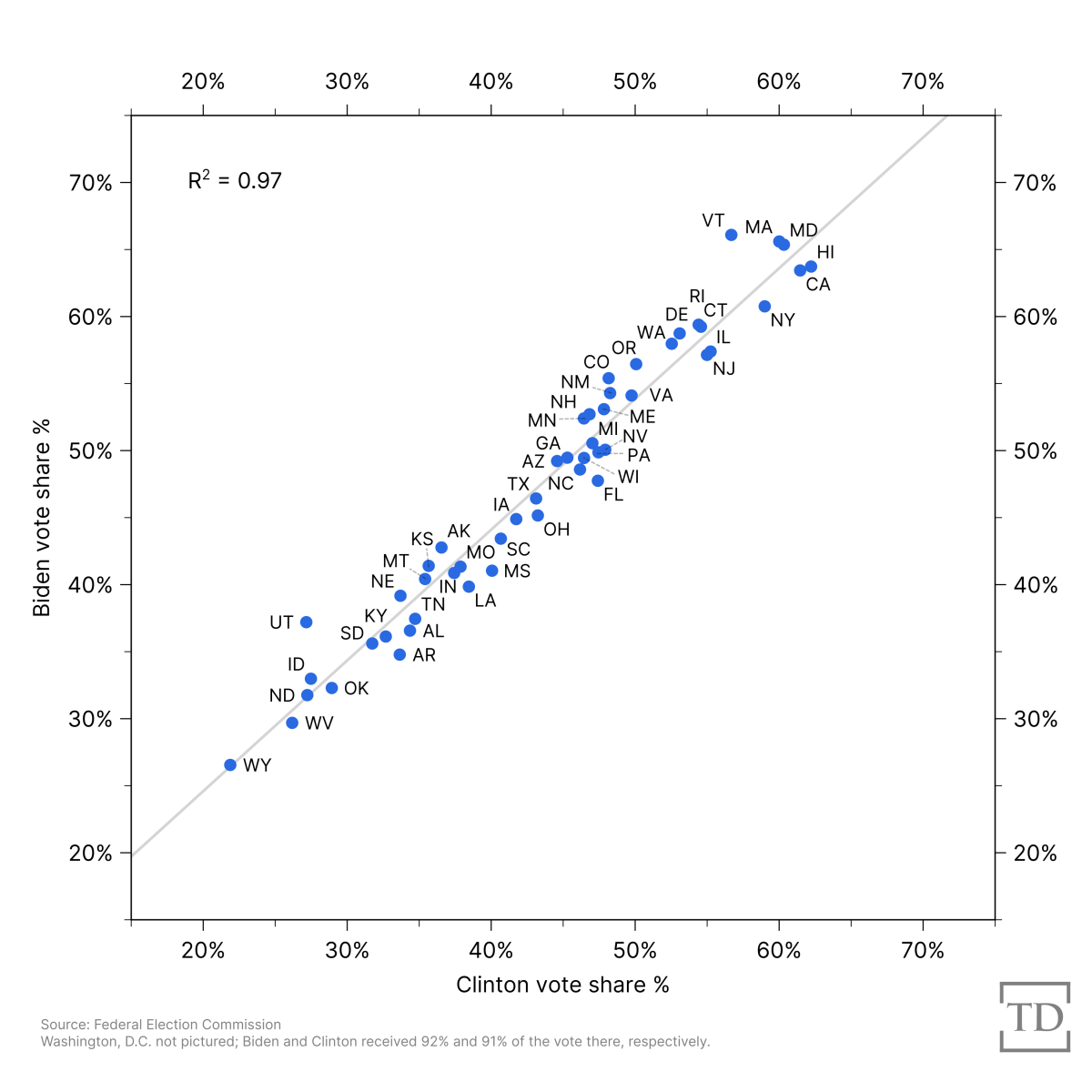

The parties are always realigning a little bit from election to election, but rarely enough to be perceptible in state-level voting data. Take the correlation of vote share for Hillary Clinton in 2016 and Joe Biden in 2020, for example:

That’s a correlation of 0.97—meaning the relationship between the two variables is remarkably strong. How Clinton performed in a state in 2016 was highly predictive of how Biden performed in that same state four years later. The polling for 2024 so far suggests that Harris’ performance in 2024 will be similarly highly correlated with Biden’s performance in 2020.

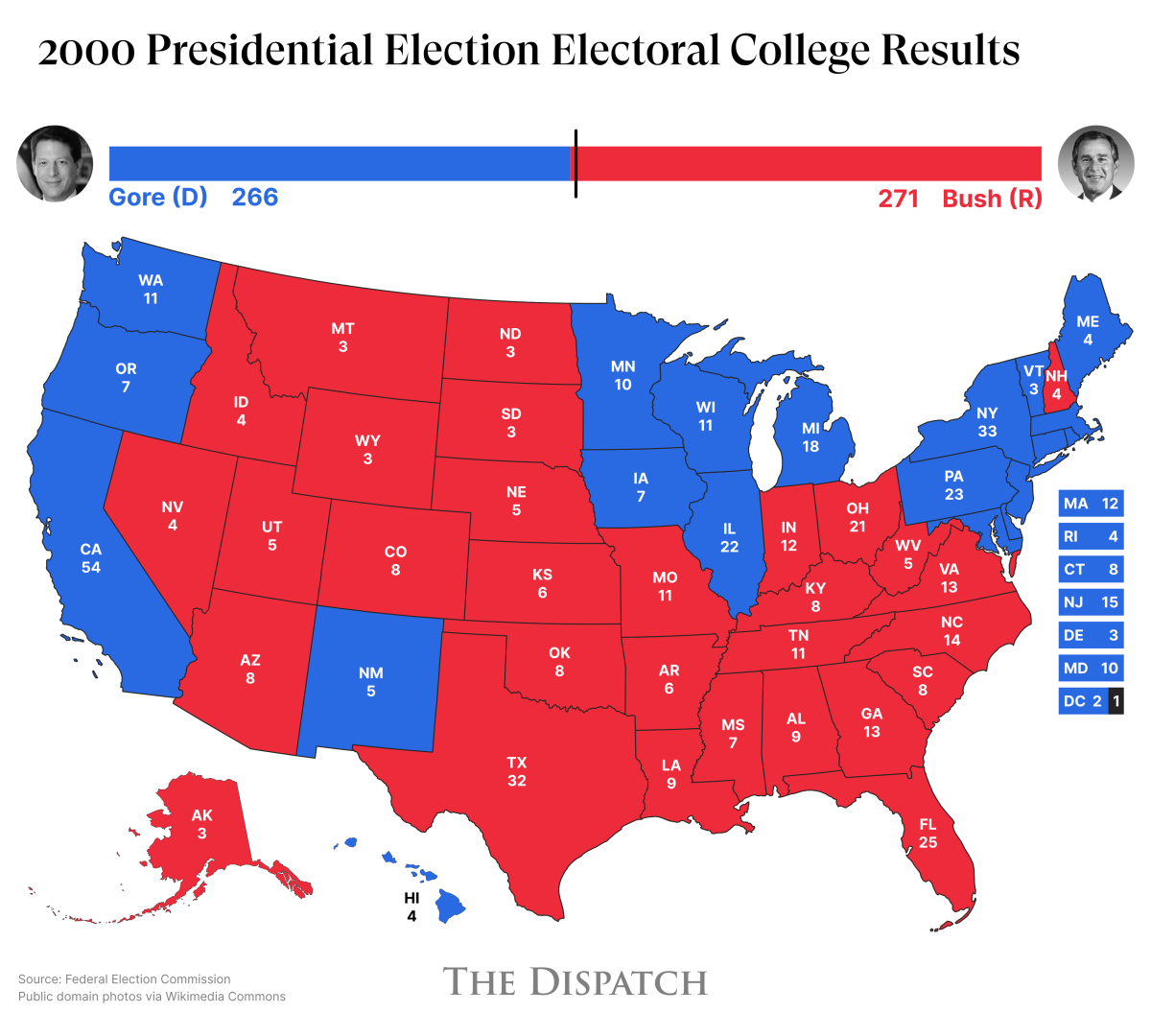

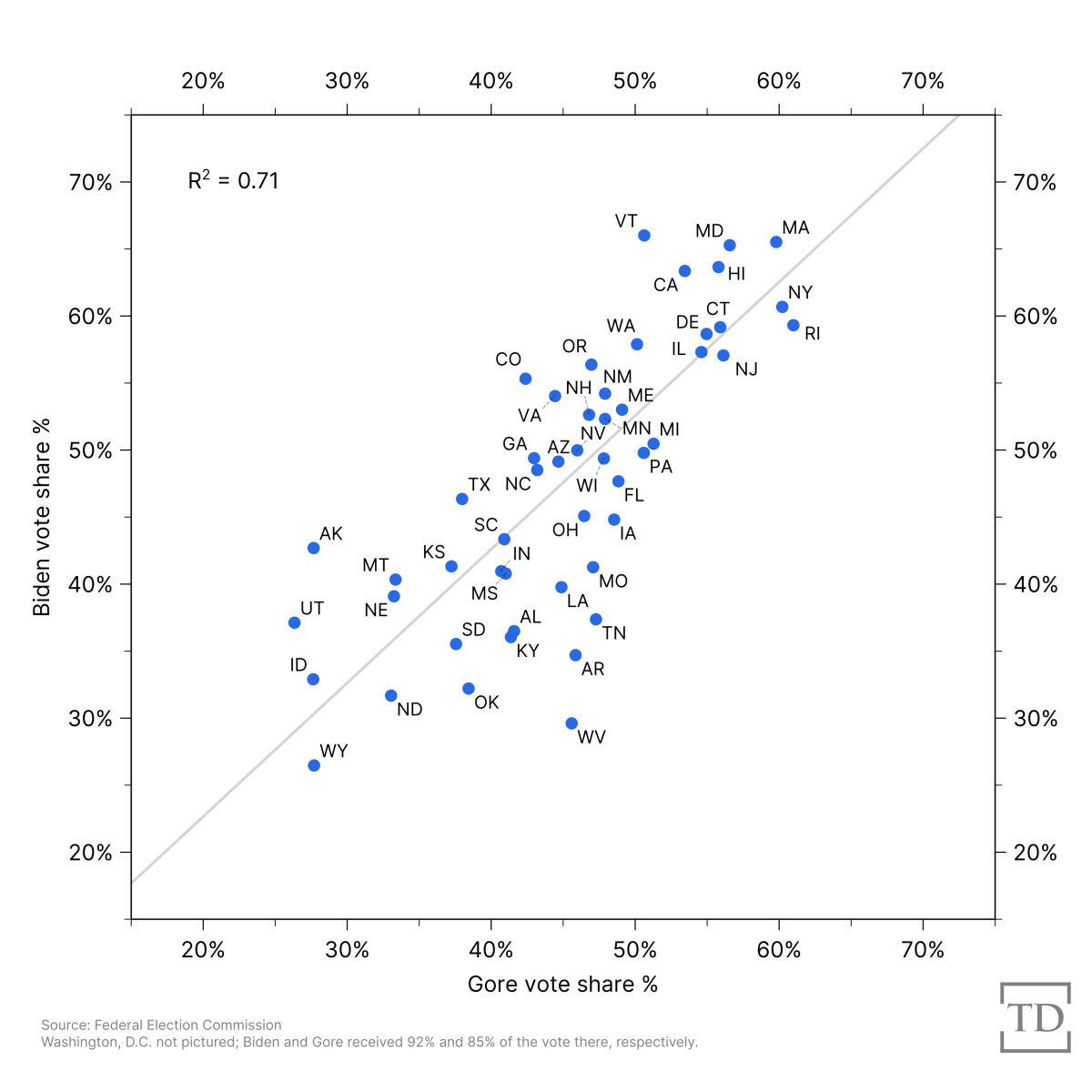

Expand the time horizon, however, and partisan shifts—while still subtle—become more visible. The Electoral College maps of 2000 and 2020 look broadly similar, with New England, the West Coast, and the Upper Midwest all leaning Democratic while much of the South and Mountain West leans Republican. But with a correlation of 0.71, the nature of the electorate clearly changed over the course of five presidential cycles. The odds of Harris winning Iowa next month are about the same as Trump winning Colorado: close to zero.

That reality is the result of a steady trend that began in the 1970s and has resulted in one of the longest competitive periods in national politics in U.S. history, with southern and rural whites shifting over time to become more Republican while nonwhite and urban Americans continue to vote in greater numbers—generally with the Democrats. In 1992, there were still enough southern white Democrats for Bill Clinton to win Arkansas, Georgia, Tennessee, and Louisiana. Georgia flipped to the Republicans four years later, and by 2000, George W. Bush won all four.

Realignment today.

The electorate has continued to evolve in the ensuing decades. One of the most notable shifts has been among non-college-educated voters in the Upper Midwest, who caught political observers by surprise in 2016 by breaking significantly with college-educated whites and voting more Republican. Biden was able to win some of those votes back in 2020—flipping Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania back into the Democrats’ column—but the steady decline of unions in the Rust Belt, along with Trump’s particularly racialized campaign appeals, has seemed to help the Republican woo some of these voters to his side in recent years.

But again, this trend didn’t begin with Donald Trump’s descent down an escalator in Manhattan almost a decade ago. Indeed, political scientist Thomas Frank outlined such shifts in his 2004 book, What’s the Matter With Kansas? Barack Obama won 60 percent of Wisconsin voters without a college education in 2008, but only 54 percent in 2012. Similarly, he won 54 percent of Wisconsin’s white voters in 2008, but only 47 percent four years later.

What Trump may have done, however, is accelerate these trends by leaning into the populist messages underpinning them. This approach is not without tradeoffs, of course, but it has essentially moved historical swing states like Ohio and Florida into the GOP’s column, made traditionally Democratic states in the Rust Belt and Upper Midwest competitive, and started to cleave off chunks of some reliable Democratic constituencies.

In fact, although a recent NAACP survey found Trump receiving a similar percentage of the black vote as he won in 2020, he’s performing particularly well this cycle with younger black men. Surveys earlier this year found Trump gaining ground among Latino voters as well, although his support there may have softened some since Biden dropped out and Harris became the Democratic nominee.

As research by political scientists Ismail White and Chryl Laird described it, community ties and social pressures have kept most black voters (around 90 percent) voting Democratic since the 1970s, with even the vast majority of self-described conservative black voters supporting Democrats during this time. But this cohesiveness may not last in perpetuity. Class could certainly overtake race as a central political identity, with less-educated voters of various races continuing to shift toward the Republican Party and Democrats becoming the party of the college-educated.

To be clear, this shift is not yet entirely complete. Non-college voters were split between the parties in 2020, with Trump pulling 50 percent of this demographic and Biden getting 48 percent. Moreover, wealthier voters continue to skew more Republican. Trump defeated Biden 54 percent to 42 percent among voters making more than $100,000 per year, while Biden beat Trump 55-44 among those making less than $50,000. This sort of split doesn’t seem likely to wash away overnight. Nevertheless, subtle realignments are always occurring, and we could see more development along these lines.

Another area where we’re seeing at least the potential for some subtle realignment is over the Israel-Gaza War. Roughly two-thirds to three-quarters of Jews have voted for Democratic presidential candidates for the past four decades or so, and that hasn’t shifted much. But in part due to recent waves of immigration, the Democratic coalition now includes more Muslims who, in general, have less favorable views toward Israel. Moreover, liberal American Jews have remained strongly Democratic while becoming more vocal critics of Israel as that nation has become more outwardly militant. Even if elected officials of both parties continue to support Israel rhetorically, the Democratic Party is increasingly the home to both Israel’s critics and to most American Jews, creating a tension that could result in further shifts.

There’s another subtle area of realignment that, while harder to measure, seems to be important: populism. To be sure, there are both left-wing and right-wing populists. The former generally sees banks and billionaires as the problem. The latter generally blames “cultural elites”—whether entertainment moguls, government bureaucrats, or Ivy League professors. But they agree that today, “regular Americans” are getting screwed.

During the Biden administration and in the transition to Harris’ candidacy, left populists (Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, etc.) have been able to work well with their establishment co-partisans. Right populists, by contrast, have fundamentally taken over the Republican Party and largely purged those who weren’t on board. Thus conspiratorial thinking, government distrust, and resistance to things like vaccines and product safety laws and governing institutions themselves—while once fringe views in both parties—have become largely the province of the GOP. This is part of the reason why a longstanding conspiracy theorist like Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., who grew up on the Democratic left, now finds common cause with Donald Trump.

The coming realignment?

For all the talk over the past few years about a coming realignment, the fact remains that it is very hard to see one approaching. Not only are realigning elections very rare, but we’re also amid an era of very close national elections with just subtle shifting between parties.

That said, put yourself in the position of a political pundit in September of 1929. Noting decades of Republican dominance in national politics, you would have had little reason to believe that an economic cataclysm was just weeks away. Yet those events would lead to a tectonic shift in the electorate and half a century of Democratic control.

What we’ve seen so far this year suggests that the electorate is breaking down in similar ways to how it did in 2016 and 2020, and specific swing states are not much of a surprise. But the potential for Donald Trump’s political career to end one way or another in the next few years, or the potential for the nation to elect a black woman as president, each have the power to cause some important shifts in how the parties line up and how they view themselves.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.