Russell Moore’s new book asks all the right questions, and it calls evangelicals to ask all the right questions too: about our own institutions, our own personal integrity, and about a culture largely down on evangelicals.

Losing Our Religion: An Altar Call for Evangelical America isn’t the hand-wringing screed some of Moore’s harshest critics—of whom there are plenty—probably think it is. Still, he doesn’t pull any punches, whether in diagnosing problems within American evangelicalism or in offering pastoral prescriptions at the end of each chapter. Before becoming editor-in-chief at Christianity Today, Moore spent decades as a pastor, seminary professor, and leader in the Southern Baptist Convention. He left his post at the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission—the SBC’s public policy arm—in 2021, and later the denomination itself after it bungled a number of sex scandals. Perhaps most notably, Moore became something of a whipping boy for many in the denomination—and in broader evangelicalism—during the Trump era, because of his vocal derision of the former president and his criticism of how evangelical churches have approached issues like race and politics.

Moore focuses Losing Our Religion on a handful of wider issues in which he sees American evangelicals largely failing to live up to their own theology: credibility, authority, identity, integrity, and stability. He’s at his best when he turns particular shibboleths in on themselves, highlighting how they are not only wrong in themselves but also fail to achieve their desired ends.

Take Christian nationalism, which Moore defines as “the use of Christian words, symbols, or rituals as a means to the end of shoring up an ethnic or national identity.” Those who carry its banner—such as some January 6 insurrectionists—and back a “politically enthusiastic version of Christianity” or a “religiously informed patriotism” may think they are doing their Christian duty by baptizing the law of the land. But Moore argues they’re actually imitating the enemy they seek to fight: “Christian nationalism cannot turn back secularism, because it is just another form of it.”

Through these critiques, Moore implicitly asks whether Christians believe what they say they believe—that the good news of Jesus Christ’s death and resurrection that they preach on Sundays is sufficient to change individual hearts—even in what they’d call a wayward culture.

Christian nationalisms and civil religions are a kind of Great Commission in the reverse, in which the nations seek to make disciples of themselves, using the authority of Jesus to baptize their national identity in the name of the blood and of the soil and of the political order. The gospel is not a means to any end, except for the end of union with the crucified and resurrected Christ who transcends, and stands in judgment over, every group, every identity, every nationality, every culture. Christian nationalism might well “work” in the short term in cementing bonds of cultural solidarity according the flesh. But apart from the shedding of blood there can be no forgiveness of sins.

Moore later points to Ireland as an example of how cultural Christianity—albeit of a much different sort than what evangelicals would profess—can undermine itself. The once thoroughly Catholic Ireland, particularly on abortion and divorce, has now swung the other way. The blame, Moore argues, doesn’t fall on liberal boogeymen. “Did these massive and unpredictably sudden changes happen because of dramatically improved mobilization or messaging tactics by the (to use an American framing) ‘cultural Left?’” No, he answers. They happened because of the moral failures of the scandal-plagued Catholic Church itself. “It was because people who once revered the church came to believe that the church did not itself believe what it taught.”

Moore peppers the book with personal experiences of how fellow church leaders, largely within the SBC, attacked him for criticizing Trump or the SBC’s response to various scandals. Many of those interactions, as Moore relates them, reflect what you expect of leaders who want to maintain their own influence. “This is not how you play the game,” Moore says one such leader told him. “You give them the 90 percent of the red meat they expect, and then you can do the 10 percent of side stuff that you want to do, on immigrants or whatever.”

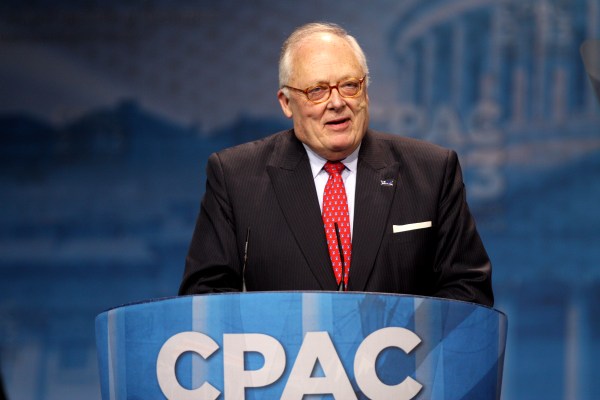

Such failures of personal integrity take the brunt of Moore’s criticism. He’s especially critical of a tendency to forgo the right conduct or peddle lies due to ambition, influence, or plain old convenience. That’s why someone like the seemingly shameless Jerry Falwell Jr. went so long without real accountability from Liberty University’s board of trustees. (Thanks to Moore for reminding us that Jerry Falwell Sr. said both Bill Clinton and then-New York City Mayor Rudy Giuiliani should resign from their respective offices since lack of personal integrity matters for public servants—seems fairly prescient given current events.) Or why men like Paige Patterson and Ravi Zacharias got away with sexual abuse for years while overseeing ministries that, from the outside, appeared to be thriving.

What we have seen, often, whether publicly or sometimes secretly by boards to whom some Christian leaders are accountable, is the disconnection of personal virtue or character from achieving the goals of “winning” in the social arena, whether in politics or in the corporate mission of a church or a ministry.

While Moore’s diagnoses of American evangelicalism are profound, much of his advice to evangelicals boils down to elemental theological tenets like trusting God and doing the right thing even when tempted otherwise. But here’s where Losing Our Religion could be stronger: Moore could have directly addressed those evangelicals who now support more authoritarian regimes (either ecclesiastical or political) not out of selfish ambition to maintain their own cultural influence, but out of sincere concerns about a rapidly secularizing culture.

“Some would suggest that the grievances were specifically theological or ideological—and yet survey after survey show that the issues assumed to be of most importance to evangelical Christian culture-warriors—abortion or marriage, for instance—are of much lower priority than issues that are far more “secular” and yet far more emotionally visceral: namely, immigration and race.”

You can take Moore’s point even without spending too much time in an evangelical church and notice that many of the evangelicals he writes about weren’t at the Capitol on January 6 or in Charlottesville in August 2017. Many are repulsed by those events, but they are also convinced they have no other option besides the authoritarian right. Losing Our Religion makes reference to “lesser of two evils” arguments, but at times Moore seems to talk past them.

Since Moore has become such a divisive figure within evangelicalism—a fact damning in itself—I fear not enough evangelical churchgoers who would learn from or be encouraged by Losing Our Religion will bother to pick it up. He need not waste ink in trying to address his Very Online and curiously obsessive critics. But instances like his discussion of immigration and race above, or about which doctrinal issues rise to the level of leaving a particular church or denomination, as Moore did, provided opportunities for Moore to do more persuading than he does.

Still, despite the fractured moment we Christians find ourselves in, for those with ears to hear, Moore offers help and hope: “As we will see time and time again, both in Scripture and in the history since, God often tears apart the unity of the people … in order to form a unified people. After all, unity around the wrong things is no real unity at all.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.