Lorne Michaels once said that the best cast of NBC’s Saturday Night Live was the one from when you, the viewer, were in high school.

At the risk of contradicting the man who created and has helmed the show for most of its 50-year history, I’ll note this is plainly incorrect. The show was uneven during my high-school tenure, beginning with the departure of SNL all-timer Will Ferrell and ending just as the Lonely Island was catapulting SNL into the digital video era. It wasn’t always bad, but it wasn’t nearly as great as the show had been or would be again.

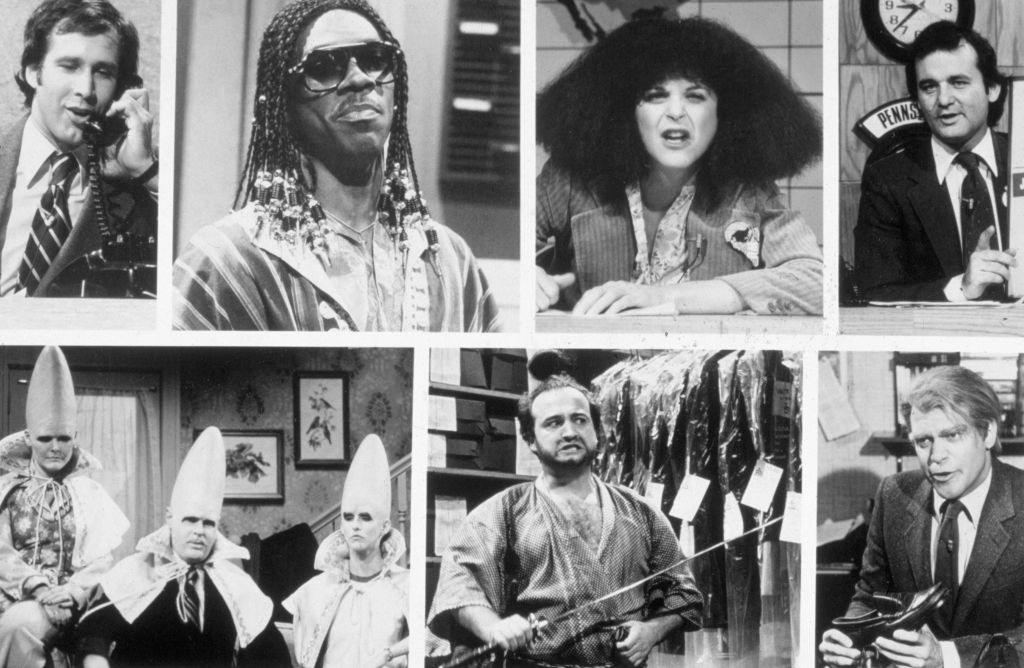

Not only was I not in high school during the greatest cast, I was not quite yet born when the show’s golden era began. The single best run for SNL—and this is indisputable scientific fact—was from 1986 to 1993. This just so happens to coincide with the tenure of Dana Carvey, and in his host monologue back in 2011, Carvey said so directly, his tongue making only the slightest gesture toward his cheek: “’86 to ’93 was the beeeest.”

He was right. That time was the closest the show came to fully realizing Michaels’ vision for SNL: as a proving ground for unknown but brilliant comedic talent to deliver a live comedy show for and about television.

From ’86 to ’93, all the pieces were there. Michaels had near-total creative control, an absolute murderer’s row of comedy writers, and a cast of professional comic performers that included Phil Hartman, Jan Hooks, and, later, Mike Myers, and Chris Farley. And it was a time when television had matured into a medium ripe for parody. More than any other period, the show’s writers and stars were tuned into what all of America was watching. That meant, for SNL, network news and MTV, aging late-night talk shows and cheesy daytime talk shows, game shows and soap operas and local-access and mail-order advertising and public television and sports talk and holiday specials and much, much more.

This era wasn’t anti-establishment and revolutionary like the original Not Ready for Prime Time Players. It created no singular stars like Eddie Murphy or Will Ferrell. But more than any other time in the show’s history, it consistently delivered the thrill of live comedy to a TV audience watching comfortably at home.

This was made more clear to me after watching the final episode of Peacock’s new four-part docuseries, SNL50: Beyond Saturday Night, just one of the many parts of NBC’s PR apparatus promoting the 50th anniversary of SNL in 2025. This episode focuses on the weird, interesting failure of the show’s 11th season, the year before Carvey and company began. It is almost as if the show, and Lorne Michaels, needed a season where most things crashed and burned to be reminded of how SNL could shine.

Michaels, having left the show after the 1979-1980 season along with the remainder of the original cast for a mixture of creative and business reasons, came back in 1985 to an SNL that had been under the dominion of executive producer Dick Ebersol since 1981. Ebersol had seen ratings success, anchored first by Eddie Murphy and later by Billy Crystal, Martin Short, and Christopher Guest. But upon his return, Michaels revamped the entire cast and brought back writers from the original era like Jim Downey, Al Franken, and Tom Davis to run the day-to-day of SNL.

It was a disaster. The cast was a bad mishmash of established actors with little experience in live comedy and up-and-coming comedians. The writers had little rapport with the cast members, which made it difficult to fully harness their comedic talent. Sketches were sometimes tonally dark or cruel, often overly complicated and dull, and rarely ever, you know, funny. It’s no surprise that the few bright spots—Jon Lovitz’s and Nora Dunn’s fully realized characters, or Dennis Miller’s smartass takes on the news for the “Weekend Update” segment—came from the cast’s actual professional comedians. Those three were also the only survivors of the post-season purge, after which Michaels got his second second chance to build his version of SNL.

The new cast in 1986 were all pros, veterans of either the booming stand-up circuit or the L.A. sketch-comedy outfit the Groundlings. The writers—including all-time great Robert Smigel, George Meyer, Bonnie and Terry Turner, and Christine Zander—now had reliable partners with whom to build characters and performance on top of the written sketch. And for Michaels, it was a rediscovery of what had made the first five years of SNL such a special, lightning-in-a-bottle experience. And now, he was professionalizing it.

The first sketch of the first show of the 12th season demonstrates how much Michaels had figured out the puzzle. Carvey and Hooks played contestants on a game show called “Quiz Masters” with Hartman as the host. The actors look at ease as they embody their very specific characters: Hartman as the smarmy TV emcee, Hooks as her dowdy midwesterner Marge Keister, and Carvey as an excitable nerd. All the character details are already getting warm, hearty laughs from in the studio before the comedic premise is revealed: Carvey is a professional psychic and is answering the questions before an increasingly amazed Hartman can even ask them. The biggest laugh, however, goes to the straight woman Hooks, who deadpans, “I don’t think this is fair, he’s a psychic.”

The story goes that in the middle of the sketch, Jim Downey, the longtime writer and producer for the show, turned to Smigel as they watched offstage and gave his relieved assessment: “The audience feels safe.”

SNL succeeds when the audience at home experiences something both familiar and unpredictable. Broadcast television is supposed to be safe—after all, we allow it into our homes, we watch it with our families. We expect it to be there when we need it, like water at the sink or the light switch, and simple to stop when we’re done. But comedy can and should feel dangerous. It defies our conventions and tears apart our order and exposes something we all know but don’t feel brave enough to talk about. Live comedy is messy, full of tension and chaotic release. We laugh as a physical response to something that’s funny, but it’s not that far from screaming.

That contradiction is what fueled Michaels and the original SNL team 50 years ago: a new generation of comics who grew up knowing television and tapping into the revolutionary impulse to blow it all up. It’s perceived as a crutch that to this day the show so often returns to the wells of game shows and talk shows for its sketches, but lampooning TV is in the DNA of SNL. You can see that in the commercial parodies and the mainstay “Weekend Update” segment that parodies the self-serious news broadcast. The audience is laughing at the absurdity of blue jeans with a third leg. This comedic idea is packaged in a recognizable TV commercial format, which is itself funny because we’ve all noticed all those silly things they do in ads these days. It’s a funny-familiar feedback loop.

It’s true that there were plenty of duds, misfires, and just-plain-bad sketches during this time—just watch anything from the 1991 Steven Seagal-hosted episode. And despite the unending stream of classic characters and sketches—the Church Lady, Master Thespian, Wayne’s World, Opera Man, Hans and Franz, the Richmeister, the McLaughlin Group, Pat, the Chippendale’s dancers, Bill Swerski’s Super Fans, Mr. Subliminal, the Sweeney Sisters, Toonces the Driving Cat, the Hollywood Minute, Sprockets—there are 43 additional seasons of the show that all have more than their share of brilliance.

But what about going forward? The show is as much a relic as it is an institution for a country that has abandoned live TV for everything but sports. I can’t recall the last time I tuned in on a Saturday night to catch the show, and I’m likely to see SNL the next morning through clips on YouTube, selecting the ones that look appealing and worth my time.

It’s unclear what catchphrases or characters are really breaking through to the broader culture the way the show once defined young Americans’ comedy language. It’s not impossible—my kids were in tears watching last year’s sketch about getting “Jumanji-ed” and still quote from it today—but with the audience for new comedy much more likely to find it on social media, a slickly produced network show’s attempts to reflect this new medium always seem to fall short, coming across as a clunky parody or pastiche. Simply put, TikTok doesn’t directly translate to television.

We’re losing our shared experience of TV and, with it, the reason for Saturday Night Live to really exist. There was once a thrill at the idea that on any Saturday night, a hilarious, outlandish, unpredictable moment might happen in real time, broadcast to the entire country, watchable on the same TV set on which your parents watched the weather report. But anyone with a phone and an internet connection can go live at any time, or post short-form comedy videos as quickly as they can make them on platforms over which the creators have much more control. Can SNL, the expensive product of a major media company with 50 years of legacy behind it, keep adapting to this world?

Even if it doesn’t, we’ll always have ’86 to ’93.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.