Decades ago, my parents were subscribed to an increasingly endangered item: a print newspaper. Seemingly every other day in the pages of this dying phenomenon was a new and brief item about how eating food X causes cancer. I was no science expert as a kid reading this (I’m still not), but I eventually concluded that all these foods may give me cancer, but not eating at all guaranteed I would die. So I would take my chances.

Jesse Singal’s new book The Quick Fix discusses the dangers of popularized social science in the press, not the “harder” science claiming everything causes cancer, but I could not help but feel that the two are linked, part of a broader problem in which the complicated, contingent, and sometimes contradictory science we produce is packaged and “sold” in the media, to the public, or presented to decision makers in government.

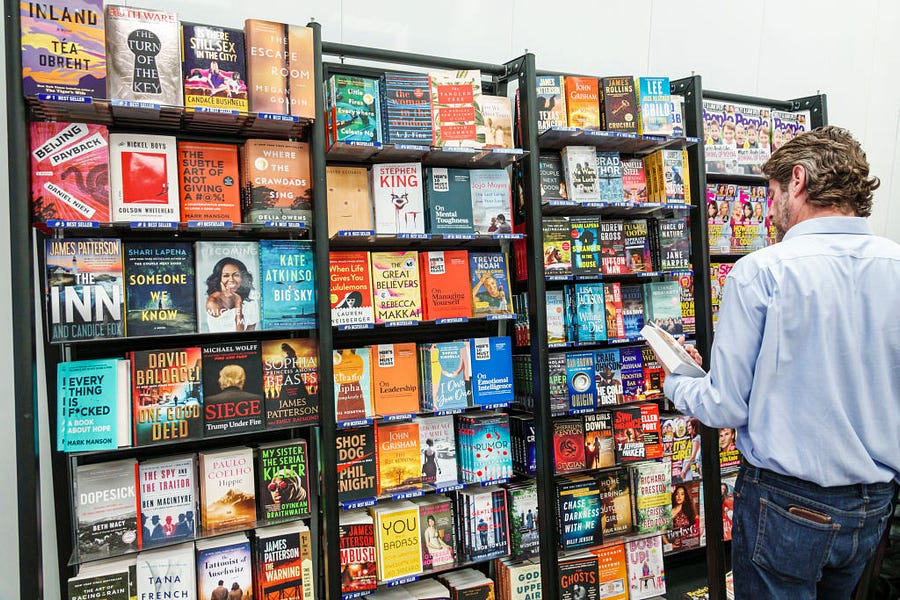

Singal, a veteran journalist with many positions under his belt, uses his experience as editor of New York Magazine’s online social science edition, Science of Us, to warn us of how all those flashy clickbait articles and airport books telling us about how we can change life and society with “this one trick” are either false or at the very least grossly exaggerated, often causing more harm than good.

Not one to shy away from controversial topics, Singal focuses on some of the biggest and most widespread of these fads—the idea of improving self-esteem as a way to improve school grades, the criminal “superpredator” as an “inevitable” result of American demographics, grit and positive thinking as ways to succeed and overcome severe trauma, “bias tests” to reveal bigoted thinking, and “nudging” as a governing midpoint between the overbearing social engineering of the post-WWII era and the ostensible “do nothing” approaches of the right.

Chapter by chapter, Singal illustrates how the American public repeatedly convinced itself that a given tactic was not only part of a problem or the solution to it but the key to fixing the social universe.

It is amazing how similar these stories sound: Someone, usually an expert with elite credentials and often working at one of the country’s top schools, proposes an idea that sounds intuitive and appears to have empirical backing. The concept is then made famous by a viral TED talk or bestselling book. The media, the public, the government, and establishment scientists either fall in line and run with that ball or are ignored when they have doubts. Only after a few years or perhaps a decade, after the initial enthusiasm has died down, do experts finally give the idea a thorough testing. More often than not, they find it wanting or even entirely useless.

The “superpredator” story in particular is one which everyone on the right concerned with criminal justice issues should read carefully, no matter where they stand. In the early 1990s, against a background of genuinely shocking violent crime rates, particularly among youth, an aspiring political scientist named John J. DiIulio published a theory arguing that the worst was yet to come.

Based on demographic extrapolations and what seemed at the time like “common sense” beliefs about growing up in poor and socially dysfunctional neighborhoods, DiIulio argued in a seminal article in The Weekly Standard and a book published with William Bennet that a wave of sociopathic monsters straight of A Clockwork Orange was about to hit America’s streets. Given the already charged atmosphere in the country over crime, and especially minority crime, DiIulio struck a nerve. Soon, public leaders and politicians on all sides were clamoring for ever tougher laws for all these would-be Jokers.

Except, for reasons still debated today, the wave never happened. At least until very recently, the crime rate in America has gone steadily downward, especially violent crime. The result, then, was a massive campaign of increasing incarceration to head off a nightmare of murder and mayhem that never happened.

DiIulio himself and others who had initially supported the “superpredator” idea repudiated it. Meanwhile, a simple look at his arguments showed gaping holes—such as equating “encounters with the police” with commission of serious crimes. Some quick fixes were at least subjected to a degree of scientific scrutiny. This idea never was—and it didn’t matter. Except, of course, for the many young people who were treated particularly harshly in criminal courts for fear they were potential barbarians.

How does this keep happening?

In Singal’s telling, this isn’t some conspiracy by grifting or manipulative scientists or power-hungry government officials. Barring hard evidence to the contrary, he assumes the good intentions of those proposing these “quick fixes.” He also notes how many of them are intuitive and are often grounded in at least some well-established research. Even if they do not tell us everything, some of the ideas do tell us something about the human condition, especially within American society, and provide useful tools for further research.

Singal tries to place, and I think usually succeeds in placing, American willingness to believe in “quick fixes” within general American cultural traditions and ways of thinking. As the late thinker Peter Lawler noted, Americans have always been Cartesians of a sort—they believe things can be solved with the right mindset, the right tools, the right equations. The idea of the “quick fix” to improve virtue or achievement easily plays on this deeply rooted belief, whether it comes in the form of prosperity Gospels or the secularized corporate “evangelism.” But the result, as Singal painstakingly documents, is harmful. It leads to Americans expecting too much from what usually amounts to minor tweaks in a flawed system and a vicious cycle of wasted resources chasing one pointless fad after another.

Singal sees these efforts at “quick fixes” as attempts to dodge the deeper structural problems of American society. Instead of solving problems of societal inequality and want which leave many Americans without the needed resources to succeed, we give them advice on working hard and “grit.” Instead of solving the housing and schooling inequalities which severely hamper black Americans, we engage in self-flagellation and identify “biases” everywhere—all without actually helping a single black American citizen get ahead.

While I sympathize with these arguments, I find them overstretched. Singal, a liberal, admits that in at least a few cases, trying to solve deeper inequality was no more successful than his “quick fixes”—“blind interviews” being one of these. Nor does he really contend with the efforts and failures of massive redistributive government efforts in the time of, say, Lyndon Johnson, or indeed similar efforts in other advanced countries. It’s not enough to just say “try harder”—we have decades of experience in these matters, and the record is at best mixed.

Indeed, the complete absence of conservative or at least libertarian thinking on top-down or institutionally driven efforts to improve society or at least its weakest members is stark. Singal doesn’t have to agree with any of it, of course, but the right has accumulated a veritable mountain of theoretical and empirical work arguing against the kind of social engineering mindset he thinks is superior to quick fixes. The arguments of Hayek, Burke, Sowell, or Murray may not be to Singal’s liking, but they deserve more than brief mentions.

Any reader of the center-right science magazine The New Atlantis would be thoroughly familiar with informed and well-argued pleas for more humility and humanity in science and scientific discourse, arguing that we cease to view scientists as demigods capable of caring for all our needs, and that we stop asking people to do the impossible in general.

Nor are conservatives bereft of ideas on how to change at least some of the “structural” problems Singal describes. Ideas such as zoning reform, school choice, removing or reforming occupational licensing so that poor people have more options —these are surely deserving of mention. They are not complete panaceas—but then, neither are any of the ideas the book mentions in their stead.

But even setting all this aside, and even if elites in science and culture become both more intellectually broad-minded and humble, I honestly wonder if that is enough. This is because the book focuses very heavily on one side of the equation—the scientists whose work is either corrupted or watered down into nothing—and not nearly enough on the other side, this being the American public.

The same American public that demands quick fixes in social science also demands the same in pretty much everything—politics, medicine, law, culture. It sets the tone when it comes to money for research, book sales, and prestige for scientists. It demands its scientific priests also somehow be prophets, despite the absolutely abysmal record of such efforts.

The question is therefore not just whether scientists can force themselves to be humbler and avoid the temptations and demands made on them by the populace, restricting themselves only to what science will allow. The real question is whether Americans will let them.

Jesse Singal’s book is a good step in the right direction for a more chastened but also more accurate and useful science for American social policy and thinking. But we still have a long way to go before we break our addiction to easy answers and quick fixes—if we ever do.

Avi Woolf is an editor and translator. He has been published in Arc Digital, National Review, and Commentary.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.