The coronavirus has hit Iran harder than most other countries so far: 1,812 Iranians have reportedly died from COVID-19; 23,049 are afflicted. Gravesites are so large they can be seen from space. For anyone who knows and cares about the Iranian people, this is a tragedy of massive proportions. So perhaps it’s not surprising that there have been growing demands for sanctions relief. But there is a difference between caring about the Iranian people and caring about the regime, and lifting sanctions will serve only to prop up the system that continues to tyrannize the Iranian people.

Last week, Bernie Sanders called for the United States to lift sanctions on the Islamic Republic, writing, “As a caring nation, we must lift any sanctions hurting Iran’s ability to address this crisis, including financial sanctions.” Sanders’s message echoed a tweet by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which likewise noted that continued U.S. sanctions are “against humanitarianism” and “hamper Iran’s epidemic response.” Joining the chorus, a group of 25 organizations led by the pro-regime National Iranian American Council also urged the immediate lifting of sanctions. The clamor falls into the now-familiar category of advocating for policies embraced pre-virus, now spiced with a COVID-19 rationale. But it is still worth unpacking the question of Iran sanctions, regime management of the virus threat, and the Islamic Republic’s overall economic policies.

Let’s start at the beginning: In 1979, Iranian GDP per capita was $2,427. Ten years into the new regime’s reign of terror, it was $2,197. Twenty years into the regime, it was down to $1,757. Forty years after the revolution, what was once one of the region’s most advanced economies, is plagued by inflation, government mismanagement, and corruption, making basics such as rent and food unaffordable. Even absent the draining Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s, the regime’s stewardship of the economy was based on a set of bowdlerized “Islamic” economic principles that, coupled with endemic corruption, destined the nation for economic disaster. “Economics,” Iran’s first Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini infamously intoned, “is for donkeys.”

Sanctions began early after the revolution, a product of the hostage crisis and Iran’s global assassination campaign that saw the murder of regime opponents and defectors across Europe, the Middle East and even into the United States. But the sanctions in place were limited in nature, focused on trade and assistance until as late as the mid 1990s. Even then, major U.S. businesses were either directly or through subsidiaries doing business with the regime, not to speak of the land-office subsidized trade between European nations and the Islamic Republic.

In short, those sanctions were far from “crippling,” and as in most sanctioned economies, Iranians learned to work their way around difficulties with help from much of Europe, Asia, and neighbors in the Middle East. It was not sanctions that cost the famously entrepreneurial Iranian people their riches; it was the regime and its disastrous stewardship of the economy. There are, however, two exceptions.

After President Barack Obama famously extended a hand toward Iran after his election—a gesture promptly rejected—Congress imposed the severest sanctions to date. The Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act hit the Iranian economy hard, along with the imposition of banking sanctions that got to the heart of Iran’s ability to trade with the rest of the world. Those sanctions were largely lifted after the signing of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the Iran deal. The Trump administration’s withdrawal from the JCPOA led to a new round of sanctions that have all but cordoned off Iran from international financial institutions, precluded the legal sale of oil and otherwise closed loopholes that, for example, allowed other states to bypass U.S. Iran sanctions unscathed.

Under the Trump sanctions, the Iranian economy has cratered. Official unemployment rose from 14.5 percent in 2018 to 16.8 percent in 2019, and unofficial employment rates are far higher. GDP has plummeted. The cost of basic goods has doubled since 2016. Two years ago Iran was exporting 2 million barrels of crude a day. It’s now down to around 300,000. The IMF was forecasting zero growth in 2020 even before coronavirus hit. As a result, the regime has needed to respond to increasing economy-driven unrest at home. Demonstrations starting in November elicited a major crackdown, with at least 1,000 killed and many more imprisoned.

Do the Iranian people blame the United States for their economic hardship? Despite shifting attitudes toward the United States (which has generally enjoyed substantial popularity with the Iranian people), polling shows the public places fault squarely at the regime’s feet. Why? Because they aren’t fools. They are well aware what their government is up to, both at home and abroad. Abroad, Iran’s costly commitment to Syria’s Bashar al-Assad has exhausted resources. The war in Syria is estimated to have cost the regime from $30 billion to $100 billion. Then there’s Iran’s arming, payment, and sustenance of Hezbollah, which costs an estimated $700 million a year. Iran also transfers cash to Palestinian terrorist group Hamas to the tune of $100 million per annum. And don’t forget Iran’s arming and support for Yemen’s Houthis, another several million dollars a year. Finally, there are Iran’s costly adventures in Iraq, the scope of which was revealed in a series of leaked intelligence reports published by the New York Times and The Intercept last fall. (Indeed, the Islamic Republic is so committed to its anti-Western agenda in Iraq that on March 12—in the midst of its coronavirus crisis— it allowed its proxies to launch an attack on Camp Taji, north of Baghdad, resulting in the death of two U.S. and one British servicemen.)

At home, another persistent fly in the Iranian economic ointment is outright theft. In this, the regime’s mullahs resemble the run-of-the-mill regional kleptocrat. It’s not just that current Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s holdings alone are estimated at $200 billion: Food and medicine budgets—for goods which are exempt from sanction—have been plundered by the regime. In 2012, the then (and promptly sacked) health minister complained that of $2.4 billion allocated for medicine imports, only a quarter had been delivered, while subsidized dollars had been used to import luxury cars.

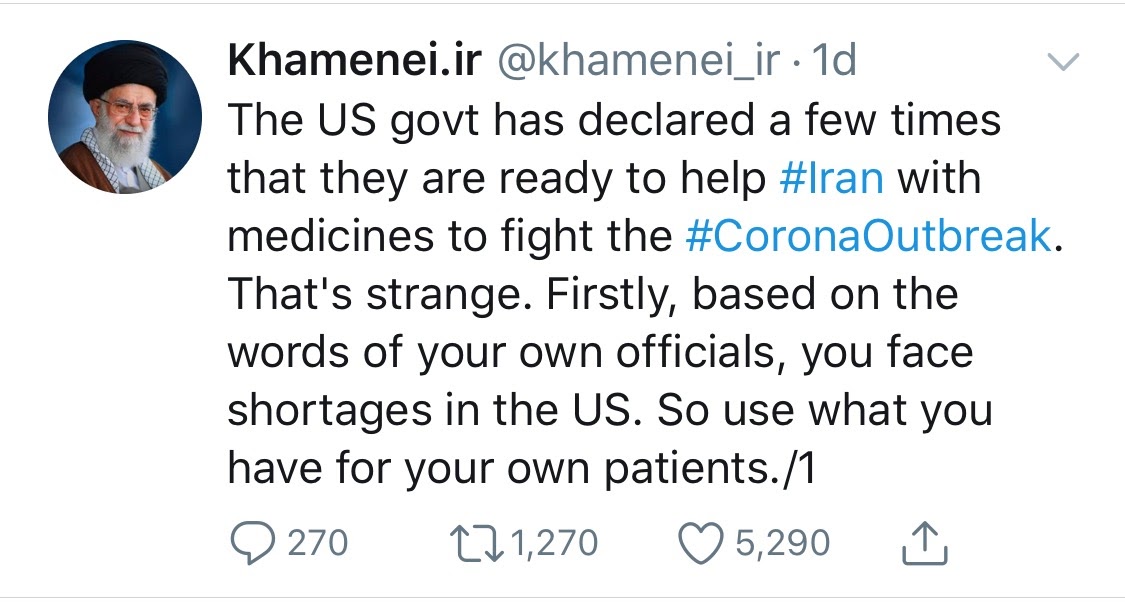

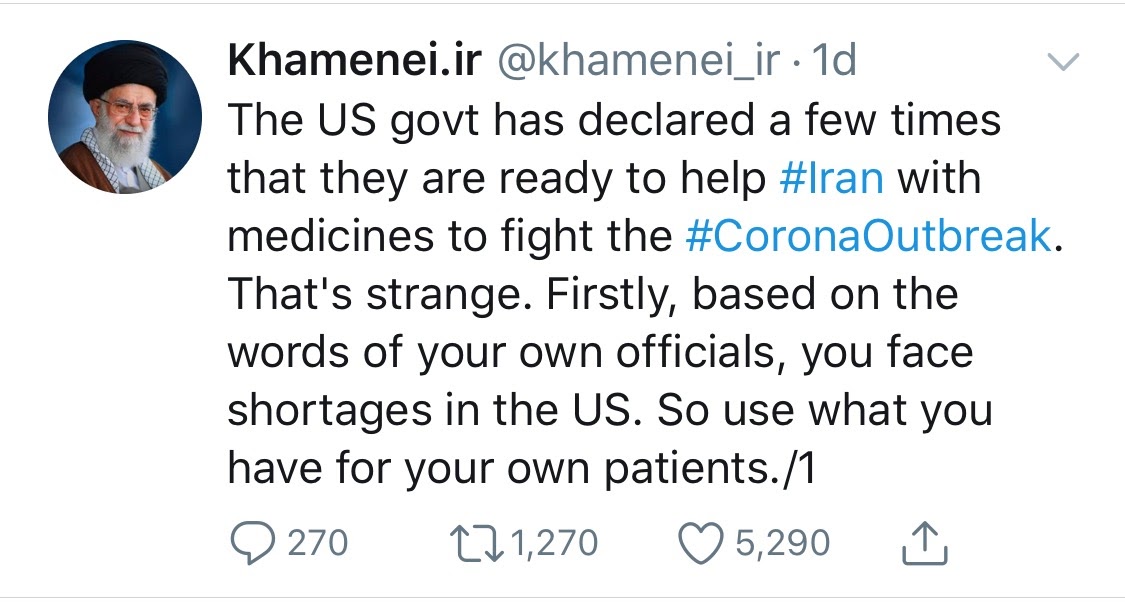

Then there’s the Cuba-style scandal of stockpiling key medicines for regime friends and officials. And the false stories blaming sanctions for deaths. Not to speak of the rejection of an offer of U.S. assistance during the coronavirus crisis. And finally, in reaction to an aggressive campaign of disinformation from the supreme leader himself, yesterday Secretary of State Mike Pompeo alleged that the regime has plundered over a billion euros slated for food and medical assistance.

Of course, it is possible that there are genuine shortages of medicine in Iran despite their availability on the global market and despite, again, the fact that medicines are not subject to sanctions. The goal of the Trump administration’s policy, it insists, is not to punish the Iranian people for the sins of their leaders. When the moment finally comes that the Tehran regime ends its costly support for the Syria war, Hezbollah, Hamas, Iraqi proxies, and others, it may be necessary to further alleviate pressure by sending food and medicine directly to Iran that it cannot secure the credit to buy. But as of now, that moment looks as remote as ever. As always, the regime prioritizes its campaign of regional terror above the lives of the Iranian people.

Handout photograph of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani making a statement about coronavirus on March 24, 2020, by Anadolu Agency/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.