Since March, millions of students have been out of school. Nearly half of the nation’s 50 largest school districts haven’t yet reopened or are only now planning to do so. Hybrid reopening plans have been a start-and-stop, hit-and-miss endeavor. Given the mounting evidence that the public health risks of reopening schools are modest and manageable, it’s no surprise that parents are growing more supportive of in-person schooling.

Here is a moment for educators to rise to the challenge: to insist that schools safeguard the well-being of staff but also that they find ways to serve their charges. Unfortunately, a rather different narrative has taken hold. Indeed, last week, El Paso teacher Lyn Peticolas took to Education Week—K-12 education’s newspaper of record—to publish an op-ed titled “What Demands to ‘Open Schools Now!’ Sound Like to a Teacher” in which she ardently denounced the “coronavirus-deniers” who hurl “vitriol” at school districts for not reopening.

Utterly ignoring that thousands of private schools have reopened without incident, that many thousands of public schools have safely opened their doors, or the grave concerns about remote learning, Peticolas waxes enthusiastic about the miracles of virtual teaching before declaring that the “sole aim” of those seeking to reopen schools “seems to be to cause strife and unrest.” She goes on, at great length, to explain how overburdened and underappreciated teachers are.

Indeed, the notion that only the callous and the cruel would ask teachers to return to school has become something of a meme in the edusphere. As an CNN op-ed by teacher Elana Rabinowitz proclaimed, “I teach public school. I love my students. I don’t want to die.” In a tack that must surely have prompted an eye-roll or two among some of the nurses or first responders busy working a second shift as homeschool parents, Rabinowitz thundered, “We want to be there for the kids, especially now. But who will be there for us—the educators? The ones who ... are literally being asked to risk our lives so the economy could go back to normal?”

Other educators have weighed in to insist that demanding “teachers return to in-person schooling shows a callous disregard for teachers, their families and the communities they serve.” They’ve said that they “want to serve the students, but it’s hard to say you’re going to sacrifice all of the teachers, paraprofessionals, cafeteria workers and bus drivers.”

This would all be more credible if the teachers who said this were signaling a willingness to do everything possible to serve their students remotely. Instead, districts across the land have reduced the hours teachers are expected to work and reduced expectations regarding teacher accountability. Meanwhile, millions of vulnerable students have fallen off the grid. The Dispatch reported on the problems documented in the Los Angeles Unified school district in September; the situation is regrettably proceeding pretty much as we feared.

There are, of course, real challenges when it comes to reopening schools safely and responsibly amid COVID. Teachers and staff have a right to expect that schools will protect their physical well-being, with appropriate practices and precautions. As we’ve argued since May, reopening needs to be pursued consistent with the dictates of public health. But it’s also true that a raft of research has now made clear that schools are surprisingly safe and that reasonable precautions should suffice in all but exceptionally hard-hit communities.

The problem is not with an educator’s desire for appropriate precautions, but with the purple prose, the reluctance to acknowledge the devastating consequences of extended closure, and the intimation that asking schools to do their job constitutes an attack on educators. While we should heed the dictates of public health, especially amid the latest COVID surge, the fact remains that teachers (and the rest of us) are riding buses, playing ball, and visiting barbershops across the land, even as public schools stay closed. If we expect shop clerks and sanitation workers to show up and do their jobs in person, it’s hardly outlandish for parents to ask that educators make every possible effort to do likewise.

Peticolas is simply the latest to give a public face to a drumbeat of demands expressed by teachers and union leaders. Indeed, unions have been calling to keep schools closed through next year and asking members to strike if asked to come into work.

Which makes it odd that teachers have seemingly concluded that this is an opportune moment to demand more funds. Without a hint of irony, Peticolas declares, “Every year, we ask public schools and teachers to do more, to be more” but that “we have failed to fund and staff them as such.” Of course, she could simply be cribbing from the American Federation of Teachers, which has claimed that schools need “at least $116.5 billion” to reopen and whose president, Randi Weingarten, has explained, “If schools can’t get the money they need to safely reopen, then they won’t reopen, period.”

The problem with the insistence that schools have been starved for funds is that it’s simply not so. Between 2000 and 2016, the National Center for Education Statistics reports that after-inflation, per-pupil spending increased by 20 percent. The U.S. spends $14,000 per pupil each year, is among the world’s highest-spending nations when it comes to K-12 education, and significantly outspends a number of nations that have reopened schools. Yet, even before COVID struck this spring, we were treated to New York City Chancellor Richard Carranza insisting “we are cutting the bone. There is no fat to cut, no meat to cut” even as his schools were spending $28,900 per student (and after he’d added hundreds of positions to his district bureaucracy in 2019).

Peticolas could’ve said, “Teachers have a critical job to do and we want to do it. But we need to be confident that our schools have secured protective equipment, a testing plan, social distancing, and have strong guidelines for reopening. That requires more than vague promises—it requires clear action on the part of school boards and superintendents.” That would be a winning message.

Safe to say that teachers chanting “Keep schools closed” is not. And educators clamoring for big new public outlays would do well to keep that in mind.

Frederick M. Hess is director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute. Hayley Sanon is a research assistant at AEI.

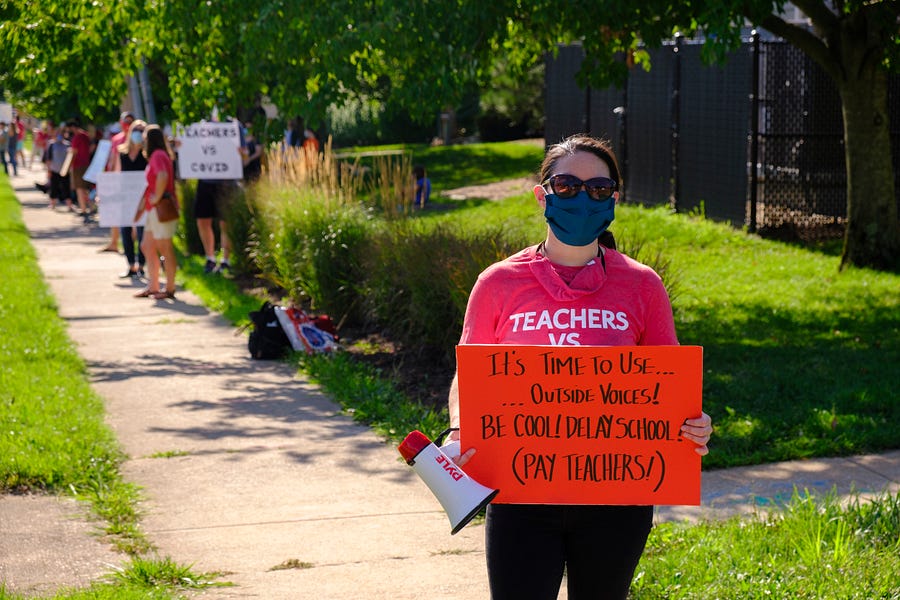

Photograph by Jeremy Hogan/SOPA Images/LightRocket/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.