People have been saying “We need to run government like a business!”—and trying to do so—for 200 years. The project always fails. The question isn’t whether it is going to fail again this time around, with the Silicon Valley tech mafia leading the way—the question is whether Elon Musk is smart enough to understand why it is going to fail.

OpenAI, the firm that owns ChatGPT, reportedly loses about $150 … a second. Serious people value the firm at $300 billion. And that comes after DeepSeek, the Chinese open-source competitor, came out blazing. People who follow OpenAI closely argue that the firm’s business model has some pretty steep challenges: For anyone other than hobbyists, its tools are not actually all that cheap to use. So, it is losing money at a relatively high price point while facing competition from an open-source competitor, which is bound to put downward pressure on prices.

In the frothy days of the 1990s dot-com bubble, companies without a real business model and not much in the way of customers or revenue saw—for a time—sky-high market valuations based solely on the fact that they were positioning themselves to be part of the coming digital revolution. That worked out great for a few firms and not at all for a lot more. The tech sector is a little more buttoned-down these days, but the distance between big idea and big profit remains considerable, and there is a kind of cultural aspect to it as well, as in Silicon Valley’s eternal founder-vs.-manager discourse. And even in today’s more conservative business climate, tech firms are not in the main famous for being beady-eyed stewards of cashflow—they are epic pissers-away of money, but the upsides to startup success are so rich that they can maintain a pretty high burn rate. What’s $150 a second among friends?

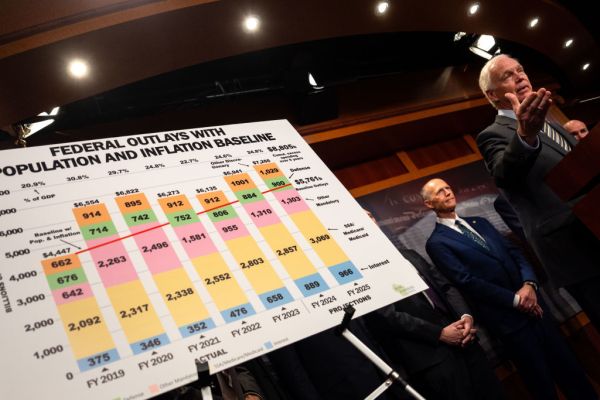

The federal government currently spends a little more than $200,000 a second. And the big idea from Donald Trump and Elon Musk is to lower that number by bringing in the sort of people who are currently overseeing that $150/second loss at OpenAI.

Musk, like many of his Silicon Valley colleagues, has made a great fortune for himself, great fortunes for many investors, and more modest fortunes for any number of employees and business partners. Our nation’s high-tech economy is a national treasure, albeit one that is driven in large part by factors that Trumpism sneers at: higher education, high finance, immigration, and globalization. It is the envy of the world, but it is based on talents and capabilities that are not necessarily well-suited to the pursuit of efficiency in government—even efficiency per se—or to the grunt work of cutting spending. In fact, the gigantic revenue gushers and sky-high market valuations that characterize successful startups have created a Silicon Valley management model that is (with important exceptions) relatively lax when it comes to spending discipline.

Even successful firms such as Apple and Alphabet have long maintained large divisions that lose piles of money while offering no obvious path toward the creation of a profitable product. In theory, a lot of that is portfolio-building, a quest for “moonshot” ideas that could—someday—become big businesses. But as businesses mature, continuing to lose tens of billions of dollars on such projects becomes untenable. That’s why the big idea in the trenches over at Google these days isn’t artificial intelligence—it is job security.

Musk is probably not the best guy to run an efficiency project. It is true that since taking over the firm formerly known as Twitter, Musk, by his own account, cut about 80 percent of its work force—which very neatly mirrors the roughly 80 percent decline in the firm’s value. That isn’t efficiency—it is taking a big thing and making it a small thing. (Musk says the company is “barely breaking even.”) Jeff Bezos of Amazon, a relatively aggressive cost-manager, might have been a better choice.

But Amazon, in spite of its reputation, isn’t exactly a model of ruthless efficiency, either. Its profit margins have historically been pretty modest, in the 4 to 6 percent range, less than half of what’s recently been typical of, say, Exxon. But when you have the kind of income and growth Amazon enjoys (it lately has been the world’s second-largest firm by revenue), there isn’t a lot of pressure to switch to cheaper coffee in the break room or count paperclips. If you can find business leaders and entrepreneurs who can deliver Silicon Valley-style explosive growth, you don’t keep them on a short leash or nickel-and-dime them. You just enjoy your dividend. OpenAI is losing a ton of money right now—but it is not right now that most investors are thinking about. Initial losses are part of the natural order of things in that kind of business.

The big tech startups have not been successful because they are themselves efficiently run businesses—they have been successful because they provide tools to achieve efficiency in other businesses, and throughout other industries. That is what drives their revenue and share prices. Facebook provides a way to circulate information (and disinformation!) much more cheaply than you could with a 20th-century-style daily print newspaper—and it does so irrespective of whether Facebook itself is efficiently run. People who earn money through Substack or Etsy or Instagram don’t necessarily need those businesses to be efficiently managed—in fact, they may benefit from inefficiencies in the management of those businesses. They just need them to provide efficiency for their own purposes. Unless YouTube is so badly run that it ceases to operate, Mr. Beast is going to be just fine.

And, for their part, successful new entrants to the tech-startup hall of fame will probably in most cases follow roughly the same pattern as their predecessors: burning through money with relatively little discipline during an initial stage of dramatic growth before either settling into corporate maturity or burning out. There are not a lot of lessons in any of that for achieving fiscal stability in government.

Washington’s problem isn’t that it lacks bold new ideas—it is that people who have to run for election every few years are disinclined to do hard, unpopular things. If straightening out the federal books were mainly a matter of boosting revenue or coming up with big, profitable new ideas, then looking to the tech sector for advice and inspiration would be the most natural thing. But what Washington mainly requires is the old-fashioned bean-counting stuff, and the tools that will get the job done have been with us since Luca Pacioli invented modern accounting in the 15th century.

There is one very good reason smart businessmen fail when they try to run government like a business: Government is not a business.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.