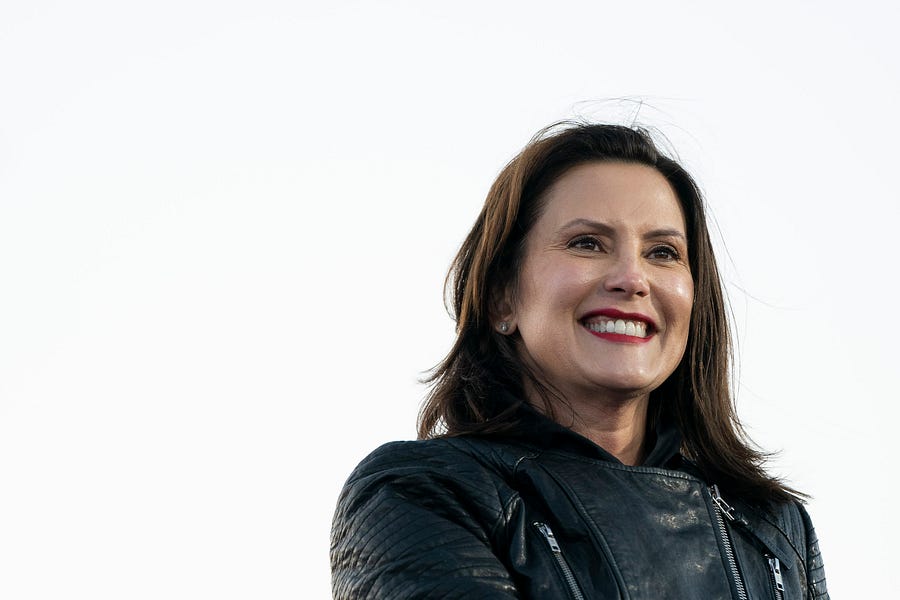

Last October, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled that Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer “lacked the authority to declare a ‘state of emergency’ or a ‘state of disaster’” under the Emergency Powers of the Governor Act (EPGA). The EPGA was further ruled to be in violation of the Michigan State Constitution because it “unlawfully delegates legislative power to the executive branch,” and “cannot continue to provide a basis for the Governor to exercise emergency powers.”

In short, all of the executive orders Gretchen Whitmer had ordered in response to the COVID-19 pandemic were unconstitutional, null, and void. Whitmer issued a scathing response, stating “I vehemently disagree with the court’s interpretation” and closing with a pledge: “I want the people of Michigan to know that no matter what happens, I will never stop fighting to keep you and your families safe from this deadly virus.”

Days after the ruling, Whitmer issued new policies governing public gatherings and mask requirements through the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS). Since then, Whitmer has adjusted these MDHHS mandates periodically.

MDHHS was not alone, as the Michigan Occupational Safety and Health Administration (MIOSHA) began drafting new, non-emergency regulations. Among them were mask mandates and social distancing requirements impacting a broad swath of businesses, including gyms, bowling alleys, restaurants, bars, health care providers, and all sport and entertainment facilities, for employees and customers alike.

The rules also prescribe onerous disinfection requirements and prohibit workers from sharing “phones, desks, offices, or other work tools and equipment.”

In the early days of the pandemic, many, including Whitmer, feared surface-to-surface transmission of COVID-19. Today, CDC guidelines identify the risk of surface transmission as “generally considered to be low.” In light of this, the decision of MIOSHA to permanently mandate strict cleaning guidelines is puzzling.

Over the past year, Whitmer relied heavily on CDC guidelines as the basis for executive orders and health policies in Michigan. But in the wake of another COVID-19 outbreak sweeping Michigan, Whitmer is charting another course. Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the CDC, recently advised Michigan “to really close things down, to go back to basics, to go back to where we were last spring, last summer, and to shut things down,” when Michigan was under some of the strictest lockdowns in the country.

Defying Walensky’s guidance, Whitmer has not renewed these stringent lockdowns as she did last spring. Speaking on Meet the Press, Whitmer explained the change by saying “I have been sued by my legislature, I have lost in a Republican-controlled Supreme Court, and I don’t have all of the exact same tools. … So we’re still doing what we can.”

In lieu of new and expanded lockdowns, Whitmer called for a voluntary two-week pause on in-person high school education, sports, and indoor dining, later expanding the MDHHS mask mandate to cover children as young as 2.

While she lacks constitutional authority under the EPGA to issue similar executive orders, Whitmer has not been shy about using other means to enforce public health mandates. Indeed, her statements last October, the sweeping regulations issued through MDHHS, and the efforts to solidify these rules permanently through MIOSHA suggest her administration remains active and powerful. As such, Whitmer’s claim that her hands are tied from taking stricter measures seems dubious at best.

What’s going on? Why is a governor who implemented some of the strictest lockdowns a year ago now hedging amid an alarming outbreak? At first glance, Whitmer’s reticence flies in the face of her often repeated refrain to enact policies “based on science and data.” She is now asserting independence from CDC guidelines, even in the face of an abundance of data on the rise of COVID-19 in Michigan. However, Whitmer, above all else, is still beholden to political science and polling data.

Walking an unsteady tightrope balancing electoral viability and political power, Whitmer must maintain that the pandemic is sufficiently dire to warrant sweeping emergency powers, but not bad enough that it requires a full-fledged lockdown like last year, even with comparable case and fatality numbers.

Whitmer’s motivations are best understood through the lens of public choice theory, which Nobel-winning economist James Buchanan famously dubbed “politics without romance.”

Fundamentally, public choice theory posits that politicians, just like consumers and firms, are primarily self-interested, and they act accordingly. Whitmer, like all politicians, prioritizes maintaining her own power, especially by winning re-election. And she is on the ballot in 2022.

Last year, Whitmer’s aggressive lockdown policies and her public, heated confrontations with then-President Donald Trump advanced her national profile. Her name appeared on the shortlist to be Joe Biden’s running mate, and she even traveled to Delaware to meet face-to-face with Biden before he ultimately selected Kamala Harris.

Today, as Michigan faces thousands of new cases of COVID-19 daily, at a similar level as the second wave last fall, Whitmer has shifted both policy and rhetoric. Admittedly, the situations are not identical, with more than 6 million COVID-19 vaccination doses administered in Michigan to date. Still, her hesitance to renew lockdowns is directly at odds with official CDC advice, which has long served as a lodestar for her administration, and her former positions.

The latest polling data may hold the answer. As the heat from the presidential election started to fade, so did Whitmer’s popularity. According to a poll conducted by EPIC MRA, 49 percent of Michiganders had a favorable opinion of Whitmer in March 2021, a drop from 56 percent favorability last September. Likewise, her unfavorability sat at 44 percent, a slight bump from 41 percent last year.

As her favorability erodes both among Republicans and a growing number of independents and Democrats, Whitmer is making a simple political calculus. With Michigan entering 14 months since her first lockdown order, fatigue is setting in, and political goodwill is starting to run out.

Renewing some of the more divisive and controversial policies would lose her even more political support. While at odds with her full-throated defense of vaguely defined “science” and “data” as the sole guide to public policy last year, the shift is a predictable one.

This isn’t the only inconsistency in Whitmer’s administration, particularly throughout the pandemic. For example, after discouraging Michigan residents from traveling for spring break, two of Whitmer’s top aides (including Elizabeth Hertel, current director of MDHHS) came under fire for leaving the state on vacation. Whitmer waved off the controversy, claiming complaints were “partisan hit jobs on my team,” and that “there have never been travel restrictions in Michigan. There just haven’t been.”

Executive Order 2020-42, a since-rescinded executive order issued by Gov. Whitmer a year before on April 9, 2020, had explicitly banned “travel between two residences,” “all travel to vacation rentals,” and, barring a few exceptions laid out in the order, prohibited “all other travel.”

A year later, Whitmer is lying about her record and this controversial order, which was partially responsible for widespread protests against her last April. At the same time, she insists past strategies were successful, calling the stark rise in cases over the past few weeks evidence of Michigan’s early success.

Whitmer’s confused messaging on her own record presents a quandary: She must tout the past year as a success while burying the political fallout, which is only growing with time.

Whitmer is also trying to preserve her political power, even as she exhausted much of her political capital last spring. Besides her ongoing power struggle over COVID-19, she is working toward other political goals, including a whopping $67 billion proposed budget for the next fiscal year.

Her scathing condemnation of Michigan’s Supreme Court in October and her protracted power struggles with the Republican-led legislature she intentionally worked around last year have very little to do with genuine public health concerns. Instead, they were both means to maintain the massive executive power she had accumulated, through the EPGA and other measures, since the onset of COVID-19.

Whitmer’s desire to maintain a firm grip on power is evident in her messaging on the COVID-19 vaccine. Early last year, the vaccine was the key to resuming normal life, with her initial reopening plan (unveiled in May 2020) identifying the “post pandemic” phase as “when we have a vaccine.”

Slowly, but surely, she shifted the goalposts further. Last August, she acknowledged that simply having a successful COVID-19 vaccine was insufficient, saying “it’s going to take some time to produce it en masse so that there are quantities available for people.” By October, Michigan would have to wait “until there is a vaccine that is widely available and has efficacy and is safe.”

By December 7, barely a week before the first person received a COVID-19 vaccine in the United States, Whitmer went as far as possible, saying “Until we eliminate COVID-19 once and for all, we must continue to wear masks, practice safe social distancing, and wash hands frequently.” This is an incredibly lofty goal, as only two diseases (smallpox and rinderpest) have ever been officially eradicated in recorded history.

Perhaps sensing the sheer impracticality of her own rhetoric, Whitmer later walked it back, but not by much. A week later, she would call for the legislature to formalize “a mandate that we wear masks until the majority of us have had this vaccine,” later clarifying that a “vast majority” of people would have to be vaccinated before any restrictions were relaxed.

By this spring, Whitmer had identified a concrete, explicit goal (a rarity for her) for vaccination: 70 percent of Michigan residents ages 16 or older. In the span of a year, Whitmer went from “until there’s a vaccine,” to “until there’s a vaccine that is widely available,” to full vaccination of more than 5 million people before she would voluntarily relinquish her powers.

With vaccination rates starting to stall in Michigan, Gretchen Whitmer may be caught in a quagmire of her own creation. Unwilling to enact the same lockdown policies as she did in 2020, and explicitly tying reopening to a specific vaccination percentage, she may be forced to tread water in the middle ground of quasi-lockdown. In the process, she may anger both those calling for renewed lockdowns and those eager to resume life free from state public health mandates, like a growing number of Americans in other states.

After spending months building a brand on “following the science” through aggressive lockdown policies, Whitmer’s attempt to rebrand as a sensible moderate and run away from her own record risks alienate her earlier supporters, demonstrate her hypocrisy, and potentially sink her chances for re-election.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.