Maria Ressa remembers her arrest and detention by Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte’s government on February 13, 2019, “the day before Valentine’s Day,” as a moment of clarity. When agents of the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) unceremoniously entered the Rappler newsroom around 5 p.m., Ressa had been preparing for her upcoming seminar on press freedom at the University of the Philippines. “We’ll go to the NBI. It’s a shock—it’s a shock, but we’re going,” she said to cameras as the group pushed through a crowd of colleagues and reporters. Denied bail, Ressa spent the night in police custody.

The hours of forced reflection proved to be enlightening for Ressa. “When they did that they unshackled me, because I could see firsthand their abuse of power. I realized that I’m going to have to fight for my rights,” she told me. “I’m also a citizen … that’s asymmetrical power.”

It’s the kind of event that might inspire one to become a politician, to improve the system from within. But after 35 years covering Southeast Asia’s ruling elites, journalist and author Ressa has no political ambitions of her own. I broached the question well into our hour-long conversation hoping to unearth a fresh development in her career trajectory. Instead I got a modest laugh and a curt head shake.

“I’m a journalist. And I think people forget that journalists originally fight power, they hold power to account. That’s always been the case,” Ressa told me. “So why did I become a journalist? And I’ve thought about this a lot—it’s because I care about justice.”

Surrounded by the many aspiring authoritarians and corrupt bureaucrats governing the emerging democracies where she lives and works, Ressa finds her usefulness in reporting. She and the news site she helped found in 2012, Rappler, “hold the line” in the Philippines, acting as a grounding force for moderates, defenders of democracy, and future generations amid Duterte’s strongman takeover of the archipelago.

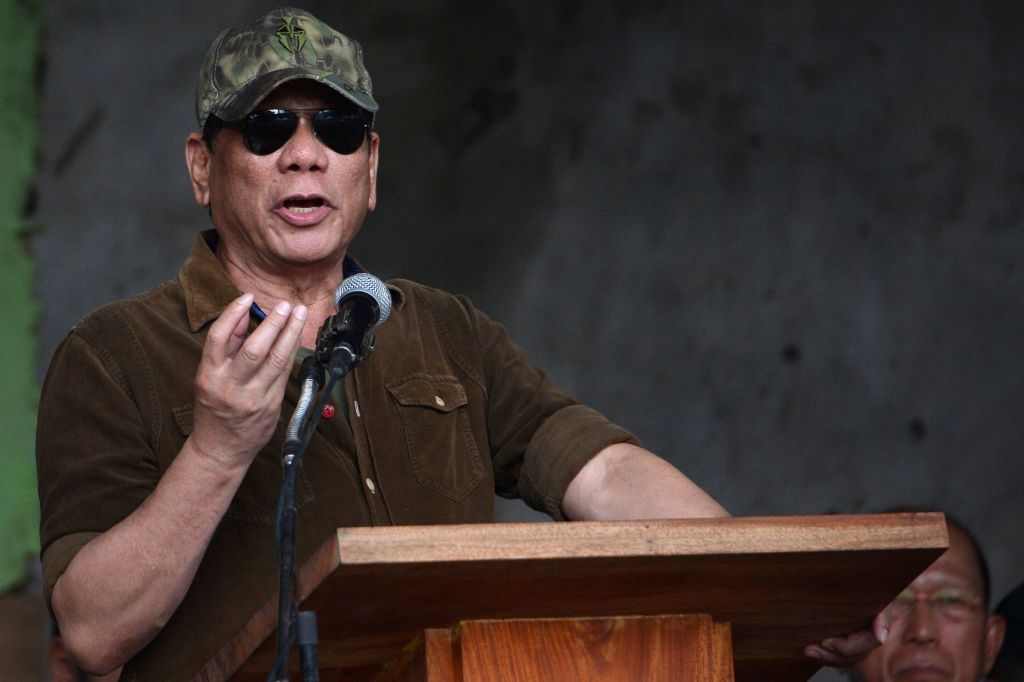

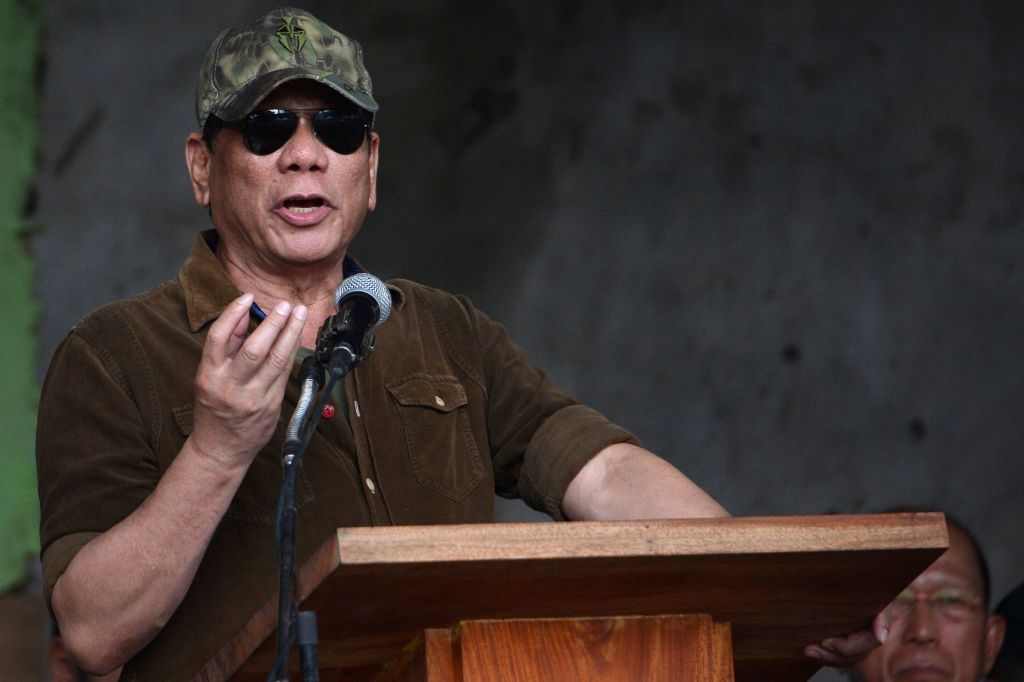

In many ways, Ressa and Duterte’s public personas have intertwined in the kind of warped symbiotic relationship reserved for the staunchest enemies. New York Times bestselling author Joshua Hammer titled his 2019 feature on Ressa accordingly: “The Journalist vs. the President, With Life on the Line.” As Ressa grows in international prominence, the president mobilizes bad-faith attacks against her to score cheap political points with his base.

With more than 427,000 Twitter followers, a documentary on her advocacy, and a string of prestigious awards under her belt—including being named Time’s Person of the Year in 2018 and nominated for the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize—there’s a case to be made that Ressa has outpaced her presidential rival in popularity, at least globally. And as Duterte ratchets up his campaign of suppression and intimidation targeting Ressa and other Filipino journalists seeking to cover his administration candidly, her name recognition—and her resolve—only grows.

But to Ressa, the rivalry is one she inadvertently stumbled into for doing her job and doing it well. The Filipino-American journalist worked for CNN during the height of its influence, covering Southeast Asia at a critical moment in its political history. As the spirit of the People Power Revolution spread from the Philippines to surrounding post-colonial states in the late ‘80s, Ressa traveled far and wide to capture it all.

“Most of my career has been about these shifts from authoritarian, one-man rule in Southeast Asia to democracy,” she said. Ressa spent the first 10 years of her life in the Philippines, but moved to the United States in 1973, one year after then-President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law. “I didn’t know where home was, because I never went back to the U.S. after the Fulbright. The Philippines was just so exciting. After I graduated, I tried to put everything on hold in the States, but my boxes from college are still in my parents’ house and I’m now 57 years old.”

In 1987, Ressa began her almost-20 year career with CNN, where she headed the Manila and Jakarta bureaus at a time when the Philippines and Indonesia struggled to find their footing in the world order, confronting issues like political instability and Islamic extremism.

The latter topic was central to Ressa’s early coverage and later the focus of her two books. In them, she charts the rise of terrorist cells in Southeast Asia in the post-9/11 period—directly linking extremist groups in Indonesia and surrounding countries to sprawling mujahideen training camps in Afghanistan.

“Islam here is a work in progress, and as such has responded often successfully to the challenges of the modern world. The growth and appeal of radical Islam in the region is not only part of a global trend; it is also part of the march of progress. The war on terrorism here is a struggle for the soul of Islam,” Ressa wrote in her 2003 book, Seeds of Terror: An Eyewitness Account of Al-Qaeda’s Newest Center.

Ressa remembers the exact date her career took a turn away from CNN: December 26, 2004, when a tsunami from the Indian Ocean hit Indonesia and killed an estimated 227,000 people. CNN wanted Ressa to cover it. She knew if she left, she might never return to the Philippines—the country Ressa had staked out as her home. “I keep coming back because I made the choice when it was easy to make the choice. I chose the Philippines,” she said.

Ressa worked out the remainder of her time at CNN in Manila before leaving to lead the news division of ABS-CBN, the country’s largest broadcaster and another target of Duterte’s ire. In January 2012, Ressa and a small group of Filipino journalists launched Rappler, which from its infancy sat on the cutting edge of investigative journalism in the Philippines, exposing the political corruption tearing at the roots of her home country’s democracy.

“We could fly in and out of all of our countries. There were times when I would get a call at 2 in the morning and I’d have to be in Pakistan when Pakistan wakes up,” she said of her time heading CNN coverage for the region. “That’s not what you do when you live in the country you report from. The reason I chose the Philippines is because I wanted to help build institutions bottom up. That was the goal of Rappler. We wanted to use social media for social good.”

The tactic, unsurprisingly, didn’t win Ressa or her colleagues many friends within the Philippine government. Although Ressa’s investigative reporting long predated Duterte’s rise to national political prominence, the president took her coverage of his administration personally.

In his 2017 state of the nation address, one year after he took office, Duterte attacked Rappler by name for its alleged violations of foreign equity restrictions in the Philippine Constitution.

“Have you tried to pierce your identity and it will lead you to America? Do you know that? And yet the Constitution requires you to be 100 percent—media—Filipino,” he said. “Rappler, try to pierce the identity and you will end up American ownership.” Ressa took to Twitter to contest the claims in real time.

Duterte’s conspiracies targeting his country’s independent media didn’t stop there. In 2019, the president’s spokesperson pushed “The Matrix,” an “exposé” published by the Manila Times identifying journalists, publications, and lawyers allegedly involved in a plot to oust the sitting government. Central to the network are Ressa and Rappler.

“The playbook is all too familiar: Utilize the media, plant fake news, distribute them to the friendly media outlets, whet the people’s appetite, arouse their anger, manipulate public emotion, touch base with the Leftist organization, enlist the support of the police and the military, then go for the ‘kill,’” the Manila Times wrote.

Enmity toward the press in the Philippines can be traced back to well before Duterte took office. Under President Marcos’ 20-year reign, the government implemented a series of crackdowns on free press to prevent the publication of content that could “undermine integrity of the government.” On November 23, 2009, 32 journalists were among the 58 violently killed amid clan warfare in the southern province of Maguindanao.

But Duterte’s leadership ushered in an entirely new beast: the large-scale dispatch of technology to target media entities deemed a threat. As “social media president” of the Philippines, Duterte—along with his supporters, abettors, and fake accounts—wage virtual war against Ressa and other outspoken members of the media.

He also uses his platform to exploit populism to its fullest, crafting a relatable online persona in an appeal to a country disillusioned by what it views as an ineffectual and dishonest ruling class. Under the Duterte regime, politicians do stand-up comedy, sing karaoke, and fill stadiums. Mocha Uson—an entertainer turned administration official—performed several sold-out shows with her “Mocha Girls” as part of Duterte’s 2016 presidential campaign. The events were planned, popularized, and streamed via social media.

By marketing himself as outside of Manila’s political elite, and capitalizing on Filipinos’ outsize time spent online, Duterte rose to power within the electoral system. But he has thumbed his nose at the country’s burgeoning democracy ever since. Extrajudicial killings by the government and its vigilante supporters—the hallmark of Duterte’s mayorship in Davao City—have taken hold nationwide, ostensibly to facilitate the Philippines’ “war on drugs.”

During a 1980s interview with Ressa in the fledgling stages of his political career, Duterte confessed to killing suspected criminals in cold blood while in office. “Davao was exactly what he’s made the Philippines, which is kind of like Wild West justice,” Ressa told me. “Because justice is slow, he takes justice into his own hands. But it’s really a pact with the devil, it’s a Faustian bargain.”

Thirty years later, as president, Duterte has been equally upfront about his government’s crude drug war tactics. “And here’s the shocker: I will kill you. I will really kill you,” he said, addressing drug users the same day a U.N. special rapporteur arrived in the Philippines to investigate the extrajudicial executions. “Your concern is human rights. Mine is human lives,” he declared during his third state of the nation address a year later.

Rappler put names to the faces of those murdered by Duterte’s regime, intimately detailing the lives and families of people found dead in the streets beginning in 2016. This diligence and compassion, perhaps more than any other component of Rappler’s coverage, has attracted the unrelenting wrath of the president.

The state keeps its own logs of individuals killed during anti-drug operations, but most international organizations don’t take them at face value. The official record reports about 6,069 deaths between July 2016 and February 28, 2021. “However, Amnesty and other civil society organizations believe these official figures are an inaccurate reflection of the true picture and that the true number of killings are in the tens of thousands,” a researcher at Amnesty International told The Dispatch.

A recent report by Dahas, an independent research body tracking Duterte’s drug war, found that at least 186 people were killed between January and March of this year.

“People will care about the death of one person who they know much more than the deaths of thousands they don’t know. And that’s in our biology, that helps normalize the violence,” Ressa said of Rappler’s quest to humanize the masses. “When tens of thousands have been killed, silence is complicit.”

But silence is also a safer space to inhabit than candor: Duterte’s death threats aren’t reserved for the nation’s drug users. “Just because you’re a journalist you are not exempted from assassination,” the president said when asked about the Philippines’ disproportionate press death toll.

To combat such threats, Rappler instituted a series of intricate disaster plans attuned to every worst case-scenario. The staff of about 100 people—63 percent women and with a median age of 23—conducts frequent drills in preparation for various shutdowns and live threats. But even steps as simple as programming reporters’ phones to go live on social media with the touch of a button can offer protection. “You have no weapons. The only defense you have is to shine a light,” Ressa explained. “Courage comes from being prepared. It’s not a pill you take, it’s from knowing exactly what you’re facing.”

When Duterte failed to subdue Ressa through traditional methods of intimidation, he turned to the most powerful tool at any authoritarian’s disposal: the weaponization of the judicial system.

Ressa was first convicted in June 2020 in connection with a May 2012 investigative story on former Chief Justice Renato Corona’s apparent ties to corrupt businessman Wilfredo Keng. During numerous hearings, the prosecution retroactively applied the contentious Philippine Cybercrime Prevention Act to try Ressa (the legislation didn’t take effect until several months after the story was published). The Manila Regional Trial Court eventually sentenced her to up to six years in prison.

Ressa returns to court today, where she’ll face her 10th criminal case and third case related to the cyber libel. Taken together, the numerous trumped-up charges against Ressa could land her nearly 100 years in prison.

The legal action against Ressa is broadly regarded as politically motivated, as activists and politicians worldwide extend their support. “It is the latest step in the Philippine government’s increasingly transparent campaign to silence her and shut down her news site, just as they shut down the leading broadcaster in the country,” said human rights lawyer Amal Clooney, an ally and friend of Ressa’s, of her most recent arrest warrant.

American lawmakers have also spoken out on behalf of Ressa, urging the government to “drop all politically motivated charges” in a joint statement following her conviction last year.

“Maria Ressa is a champion for democracy and freedom of speech. Despite the ongoing legal persecution and constant online harassment Maria faces under Duterte’s regime, she continues to work to bring truth in journalism to the people of the Philippines,” Sen. Marsha Blackburn, one of the statement’s authors, told The Dispatch. “Her work exposing Duterte’s corrupt judicial system to the world is courageous, and I am honored to have met and worked with Maria.”

“Maria Ressa’s only crime was doing her job and reporting the truth,” Sen. Marco Rubio, another co-author, told The Dispatch.

But Ressa’s battle against Duterte’s abuse isn’t relegated to the courtrooms. It has entered her home turf, the internet, where the president’s online army of bots and supporters barrage her with upward of 90 hate messages per hour. The campaign began in earnest in 2016, after Rappler published a three-part series on the weaponization of the internet. Slurs aimed at Ressa—like “Queen of Fake News,” “LIAR,” and “Presstitute,”—originated from fake accounts and spread quickly through cyberspace. They are still in use today.

According to a data analysis by the International Center for Journalists, about 60 percent of the attacks went after Ressa’s professional credibility, accusing Rappler of circulating “fake news” for profit. The other 40 percent consisted of sexist, misogynist, and dehumanizing insults. “I have eczema, really dry skin triggered by stress. I’m a journalist,” she laughed—stress is unavoidable in the line of work. “So they called me things like scrotum face. Imagine waking up to that stuff.”

“There were two goals,” Ressa added. “The first was to pound me to silence. And the second was to create a bandwagon effect, so others begin to believe a meta-narrative.”

When she began to meticulously track and record the messages, Ressa discovered that Duterte had succeeded at least in his latter goal. According to research by Rappler, 26 fake accounts on Facebook can influence at least 3 million others, and those peddling hate and anger spread their ideas faster and further. “Emotions are fantastic drivers, and they’re being manipulated,” Ressa said.

State-run influence campaigns, whether they’re targeting their own populace or that of a geopolitical rival, capitalize on pre-existing societal fault lines like identity, class, gender, and generation. While leaders have always sought to persuade and control their citizenry, the advent of social media as the world’s largest distributor of news has produced the ideal environment for government lies and deceit to thrive.

“How have facts become debatable? How is it that when I say this is a cell phone,” Ressa asked, holding up her iPhone, “to someone else who has been pounded with messages that ‘this is a cup,’ could actually believe it’s a cup? … In the age when social media has become a behavior modification system, we the users have now become Pavlov’s dogs.”

This phenomenon is the product of algorithms designed in a way that inadvertently favors the spread of lies over facts. Sites like Twitter and Facebook have a vested interest in keeping users on their sites, and reaffirming noxious world views with suggestions for like-minded people and posts is a good way to do it. But the shift away from traditional media to social media as information gatekeepers is another fundamental flaw, because, as Ressa argues, “they’ve largely abdicated responsibility.”

In many instances, social media’s failure—or unwillingness—to curb Duterte’s leverage in the cyberworld has materialized as very tangible threats to Ressa’s safety in the real world. Credible messages from internet foes vowing to kill or rape her are now commonplace for Ressa, who doesn’t entrust the local police with her safety and instead hires a private security detail.

Two Duterte loyalists live streamed their break-in at Rappler’s Manila headquarters in February 2019, a week after Ressa’s overnight detention. The men donned signs that read: “As a Filipino, I am going to hold Maria Ressa and Rappler accountable for destroying the image of my country” and “I am not a Filipino troll acting on anyone’s marching orders. I am 100 percent Filipino who can love this country more than an American will ever do.”

But despite charges by the president and his henchmen of her divided allegiance, Ressa stays put. And even with family, acclaim, and refuge in the United States, Ressa always returns to the home and career she hand-selected to be in the Philippines long before Duterte positioned her in his crosshairs. “What we do matters, you know, and I don’t want to be bullied by a bully. And I don’t want to make everything else I have done a lie, because that’s what would happen if I chose any differently from what I am doing today.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.