As a child, I would wake to the scent of rice porridge and the soft hiss of static giving way to a familiar jingle—the theme song of Voice of America. In the kitchen, my grandmother sat beside a battered radio, its bent antenna jutting upward like a crooked finger reaching for the sky. Every morning, with the solemnity of a parishioner at prayer, she tuned in to VOA Khmer and Radio Free Asia. The broadcasts came through in a haunted crackle, their voices urgent, truthful, and distant—like hope being whispered across a border.

That sound is now gone—or soon will be.

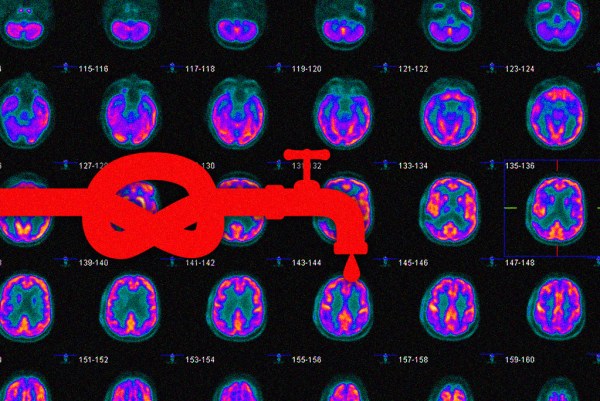

On March 14, President Donald Trump signed an executive order slashing funding to the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM), the parent organization of both Voice of America and Radio Free Asia. The directive forced RFA to furlough hundreds of staff, while VOA braces for crippling cutbacks that threaten the very core of its mission. Though legal challenges are pending, damage is already being done: VOA Khmer has not broadcast since March 18, and VOA Burmese in Myanmar last aired on March 15.

In nations like China, North Korea, Vietnam, Laos—and my native Cambodia—where local journalists are censored, imprisoned, or co-opted, these services became the last honest voices, delivering unfiltered, factual news to the most repressive corners of the world. Their broadcasts reached villagers without internet access, activists who risked everything to circulate truth, and entire generations seeking clarity beyond carefully curated mirages. For many in the diaspora, they were lifelines, windows into a homeland obscured by propaganda.

“Even if one concedes that VOA and RFA have shown signs of ideological drift, gutting their funding is not a course correction. It is a demolition.”

Following Trump’s executive order, the administration published an article on the White House website titled: “The Voice of Radical America.” It leaned heavily on the testimony of Dan Robinson, a 34-year veteran of VOA and former White House correspondent, who had written the year prior: “I have monitored the agency’s bureaucracy along with many of its reporters and concluded that it has essentially become a hubris-filled rogue operation often reflecting a leftist bias aligned with partisan national media. It has sought to avoid accountability for violations of journalistic standards and mismanagement.”

Trump’s criticisms may hold a kernel of truth—media bias, after all, is not the sole province of any one side—but the remedy he prescribed is deeply flawed. Even if one concedes that VOA and RFA have shown signs of ideological drift, gutting their funding is not a course correction. It is a demolition.

In the United States, where podcasts flourish, streaming platforms compete for attention, and independent journalism ekes out new ground each day, the information ecosystem—though chaotic—is pluralistic. Authoritarian regimes offer no such latitude. There, media is not a marketplace but a mechanism of control. The rare independent voices that persist do so in exile, in secrecy, or in fear.

For millions across Southeast Asia, VOA and RFA were neither progressive nor conservative—they were simply audible. Their role wasn’t to echo Washington’s views but to offer another view—a view unsanctioned by the regimes that dominate local airwaves.

Take Cambodia. Since the early 1990s, the country has witnessed the gradual erosion of democratic institutions under Prime Minister Hun Sen, who has ruled since 1985. Subsequent to the fall of the Khmer Rouge and the signing of the 1991 Paris Peace Accords, Cambodia briefly appeared to be on a democratic path. Yet that trajectory was slowly reversed through electoral manipulation, suppression of the political opposition, and increasing control over the domestic media landscape.

In this shrinking civic space, VOA Khmer and RFA Khmer emerged as essential sources of independent journalism. In their earlier years, they depended extensively on partnerships with local affiliates—among them the Women’s Media Center’s FM 102, Beehive FM 105, Angkor Ratha FM 95.5, and numerous other stations—to rebroadcast their Khmer-language programs, reaching audiences even in remote provinces with limited internet connectivity. Over time, as technology evolved, they broadened their distribution channels to include shortwave radio, satellite transmissions, and digital platforms such as YouTube and Facebook, ensuring their reporting remained widely accessible across both rural and urban landscapes. During elections, protests, and political crises, Cambodians turned to these outlets for uncensored information: coverage of opposition parties; investigations into corruption, land grabbing, and illegal logging; and interviews with civil society leaders and activists who had been smothered by state-aligned media.

RFA and VOA played a crucial role in informing the electorate during Cambodia’s 2013 national election—arguably one of the most fiercely contested in recent history. The Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP) won 55 of 123 seats—the closest electoral challenge to Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) in years. The CPP retained a majority with 68 seats, but suffered its steepest parliamentary losses since 1998—a setback many attributed, at least in part, to the heightened public awareness fostered by social media and these foreign broadcasts.

“For millions across Southeast Asia, VOA and RFA were neither progressive nor conservative—they were simply audible. Their role wasn’t to echo Washington’s views but to offer another view—a view unsanctioned by the regimes that dominate local airwaves.”

RFA documented mass protests over alleged electoral fraud, police crackdowns on demonstrators, and the growing unrest among garment workers over wages and labor conditions. In a country where truth had become a casualty of authoritarian consolidation, RFA and VOA offered something rare and increasingly subversive: a glimpse of reality.

By 2017, the CNRP had grown into the most formidable political threat Hun Sen had faced in decades. Fueled by mounting public discontent over systemic corruption, land dispossession, and deepening economic inequality, the CNRP again performed strongly in local commune elections, unnerving the regime and exposing its vulnerabilities. Determined to neutralize the threat ahead of the 2018 national election, Hun Sen initiated a sweeping crackdown: Kem Sokha, the CNRP’s president, was arrested on dubious charges of treason, accused of conspiring with the United States to orchestrate regime change. Two months later, a pliant Supreme Court dissolved the CNRP entirely and barred 118 senior party officials from political activity for five years.

This purge extended beyond political figures. The government shuttered RFA’s Phnom Penh bureau, revoked VOA’s local broadcasting licenses, and targeted journalists affiliated with both organizations. Two former RFA reporters, Uon Chhin and Yeang Sothearin, were arrested on spurious charges of espionage—a euphemism for continuing to report independently. More than 30 radio frequencies nationwide were shut down by authorities for airing programming from Voice of America and Radio Free Asia.

RFA Khmer’s YouTube channel became a digital refuge in exile—a vital platform for voices stifled at home. It featured human rights advocates, dissident monks urging nonviolent resistance, and young activists working to bridge the generational and geographic divides between the diaspora and domestic civil society.

Yet, as these platforms clung to life in digital form for years, the very institutions sustaining them were being choked at the source. And in fact, Hun Sen—who stepped down in 2023 to make way for his son—publicly lauded Donald Trump in March for defunding U.S.-backed media outlets.

“We should highly appreciate President Donald Trump for his courage to lead the world in combating fake news,” Hun Sen posted on Facebook. “This is a major contribution to eliminating fake news, disinformation, lies, distortions, incitement, and chaos around the world, coming from the propaganda machine that President Trump has stopped funding.”

In authoritarian states, it is not uncommon for tyrants to lash out at the press. What is less common—what ought to give us pause—is when a tyrant applauds an American president for doing the same.

What does it say when a despot finds common cause with the leader of the free world?

Indeed, the story is not Cambodia’s alone.

Across Southeast Asia, a parallel struggle persists in Myanmar, where the fight for democracy has long been waged in part over the airwaves. In the wake of Trump’s funding cuts, VOA Burmese was forced to halt operations on March 16, and RFA Burmese announced it would suspend most of its broadcasts amid the escalating financial crisis.

No one received this news more warmly than the generals in the capital of Naypyidaw. A major Myanmar military propaganda account on X posted an image declaring: “Myanmar citizens welcome the shutdown of VOA and RFA, ending years of divisive foreign propaganda that fueled unrest and weakened national unity. Ending their influence paves the way for stability, cohesion, and stronger domestic media in Myanmar.”

The military regime’s animus toward foreign broadcasters stretches back to the previous junta, which ruled from 1988 to 2011, during which time it targeted journalists with rhetorical attacks and denied most foreign journalists entry visas.

Nevertheless, millions in Myanmar tuned in religiously to the Burmese-language services of VOA, RFA, the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), BBC, and All India Radio (AIR). In fact, a 2010 report by Reporters Without Borders found that 66.5 percent of respondents listened “every day” or “often” to at least one of these international stations.

In March 2011, Myanmar’s military junta formally dissolved, ceding authority to a quasi-civilian government headed by former Gen. Thein Sein. He soon initiated political and economic reforms that included the release of political prisoners and the easing of press censorship. But even during this brief democratic thaw, when local media blossomed, Voice of America Burmese and Radio Free Asia Burmese served as the connective tissue between the diaspora, civil society, and opposition networks.

In November 2015, Myanmar held its first openly contested general election in decades. The National League for Democracy (NLD), led by Aung San Suu Kyi, won a landslide victory and assumed control of the civilian government in March 2016. However, under the 2008 constitution, the military retained substantial power: One-fourth of parliamentary seats were reserved for unelected military officials, and the armed forces continued to control the key ministries of defense, home affairs, and border affairs—along with an effective veto over any constitutional amendments.

It was a fledgling democracy, but it held on—for nearly a decade.

In the 2020 general election, the NLD once again triumphed in a landslide, further marginalizing the military’s proxy, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP). Military leaders alleged widespread electoral fraud without evidence, and on February 1, 2021, just hours before the newly elected parliament was set to convene, the military staged a coup, detaining Aung San Suu Kyi and other NLD leaders. The regime quickly reignited its war on the free press, ushering in a new era of repression. Dozens of independent outlets, including Myanmar Now and Mizzima, had their licenses revoked and were forcibly shut down. Journalists were arrested, tortured, and in some cases, killed. Internet blackouts became routine. Facebook—used by half the population—was banned.

Yet RFA and VOA did not go dark.

“What the Trump administration failed to grasp—and what many culture warriors immersed in America’s internal skirmishes continue to miss—is that this is not a culture war. It is a civilizational one.”

Consider the case of Aye Aye Mon, a journalist with RFA Burmese. In the wake of the 2021 military coup, she was compelled to flee Myanmar—but she has since returned, at immense personal risk, to bear witness to the ongoing civil war and its toll on Burmese society. “It’s an honor to provide a voice for those who need it most,” she said.

Aye Aye Mon is just one among many correspondents in the network RFA Burmese maintains inside the country, continuing to file dispatches under perilous conditions. Their reporting has exposed the military’s aerial bombings of civilian enclaves, live-fire assaults on peaceful demonstrators, and the rise of the civil disobedience movement—a grassroots uprising led by teachers, engineers, health care workers, and students who refuse to serve the regime.

Even as the regime hunted down reporters, broadcasters with VOA Burmese stitched together a fragmented resistance. Their coverage was relayed through community networks, Telegram channels, and ethnic media outlets, often translated into local dialects. Burmese exiles across Thailand, Malaysia, and the United States depended on RFA and VOA to track developments and coordinate advocacy. For ordinary citizens trapped under military rule and facing internet outages, these broadcasts—accessed via shortwave radio or smuggled satellite dishes—offered a fragile but defiant connection to the truth.

To decommission these platforms now is to achieve what the military could not: sever the cords of communication that, for decades, have sustained Myanmar’s long and unfinished march toward freedom.

What the Trump administration failed to grasp—and what many culture warriors immersed in America’s internal skirmishes continue to miss—is that this is not a culture war. It is a civilizational one. The battle is not between progressive and conservative, but between two fundamentally irreconcilable visions of power: one rooted in the dignity of liberal democratic governance, and the other in the brutish doctrine that might makes right.

In places like Cambodia and Myanmar, there is no left versus right. There is only repression and resistance. There is only the grinding machinery of authoritarian control pitted against the faint voices that dare to speak out. To frame the issue through the narrow lens of American partisanship is not only myopic—it is morally unserious.

America, insulated by affluence and fragmented by spectacle, has drifted so far from the world of flesh and blood that it struggles to name the very values it claims to uphold. When foreign autocrats cheer the muting of American-funded media, we should not mistake it for coincidence. We should recognize it for what it is: a victory for tyranny, made possible by our forgetfulness.

Liberty does not die with a bang. It dies in budget cuts and bureaucratic indifference—and in the quiet dismantling of a signal that once transmitted hope across oceans.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.