Over the past two years, an increasingly confident and belligerent China has thrust its South China Sea aggression into overdrive, fixating on the Philippines as its primary target. Manila now faces what amounts to a large-scale maritime occupation of its internationally recognized exclusive economic zone by a hostile imperial power.

China has repeatedly swarmed, blocked, and rammed Philippine ships while also deploying nonlethal but dangerous weapons such as lasers, water cannons, and long-range acoustic devices in a brazen attempt to stamp out Manila’s spirited resistance.

While China has become more obviously belligerent over the past two years, the roots of its ambition date back more than a century. Chinese maritime capabilities have improved to the point that pushing the U.S. out of the strategically important “first island chain”—the strategic line of islands stretching from the Japanese archipelago through Taiwan, the Philippines, and Borneo, serving as a natural barrier between the East Asian mainland and the Pacific Ocean—is no longer just the fever dream of People’s Liberation Army (PLA) blowhards, but an ominously plausible outcome.

Why is this coming to a head now and what can an incoming Trump administration do about it?

Obscure maps and excessive claims.

Beijing’s claim to nearly all of the South China Sea extends back to the 1930s, when its official cartographers drew ambitious maps purporting to represent the Middle Kingdom’s broad conception of its “territory.” Because China had few seagoing vessels at the time, these maps relied on old British nautical charts and a national mythology that postulated a once-great maritime superpower.

Its incredible claim—which would evolve into what became the infamous nine-dash line encompassing nearly the entire South China Sea—was so factually specious that its southernmost point was drawn around the completely submerged James Shoal, which at 22 meters below the surface would earn no territorial rights whatsoever under the 1983 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) treaty.

Even so, these audacious maps went largely unnoticed outside of China, as the country possessed no capability to project maritime power beyond its borders. For the few who paid attention, the claim was treated as bizarre and almost laughable.

Nobody’s laughing now.

The reef-grab years.

The first real indication that China was preparing to lean harder into its claims came in 1974 when it staged a brief and opportunistic naval battle to evict South Vietnam from the Paracel Island group. China was still a weak naval power, but South Vietnam’s collapsing regime was an easy mark. America, eager to extract itself from an unpopular war while courting Beijing’s realignment against the Soviet Union, had no appetite for this fight. The Paracels fell with barely a whimper.

As suggestions of oil and gas deposits beneath the seabed began to proliferate, China turned its attention even further south, joining its neighbors in a chaotic reef-grab across the larger Spratly Island group that would extend through the end of the next decade. With six different countries claiming some part of the archipelago, the potential for conflict escalated until a 1988 dispute over Johnson South Reef ended in the massacre of 64 Vietnamese soldiers in a short and lopsided battle with the PLA Navy.

After this, the contest over South China Sea “features”—the various islands, reefs, and shoals of uneven legal status—subsided for a time, as all parties seemed content to assert their claims in less bloody fashion.

While China gradually expanded its naval capabilities, however, it found innovative ways to press its expansionist agenda by exploiting the “gray zone”—that murky space short of war where an aggressor seizes the advantage over its adversaries while avoiding the costs of its aggression.

Opacity and deniability are the coin of the gray-zone realm, as they paralyze the adherents to the U.S.-championed “international rules-based order” by sowing uncertainty and discord among its risk-averse, consensus-seeking rules followers.

Such was the case for China’s next big move—its 1994 placement of “fishing shelters” upon Mischief Reef, which went unnoticed for months. The UNCLOS treaty defines a country’s exclusive economic zone as extending 200 nautical miles from its shores, and Mischief Reef is a little more than 150 nautical miles from the Philippines. It was the first time a claimant country had put structures in another’s exclusive economic zone.

Caught off guard, the Philippines’ only available counter was to run a U.S.-donated World War II-era Navy ship, the BRP Sierra Madre, aground at nearby Second Thomas Shoal in 1999. As we will see below, this makeshift military outpost would become a key flashpoint in the years to come.

Having recently abandoned its huge Philippine military bases following years of contentious negotiations with its former colony, the U.S. did little in response. A few fishing shelters on lonely reefs hardly seemed worth the price of aggravating an emerging economic partner with a billion potential consumers on the verge of World Trade Organization integration.

The only remaining check on China’s aggression remained its self-perception that it was not yet ready to directly challenge U.S. primacy. This reticence found voice in Deng Xiaoping’s “24-character strategy,” which cautioned: “Observe calmly; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide our time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership.”

The end of ‘hide and bide.’

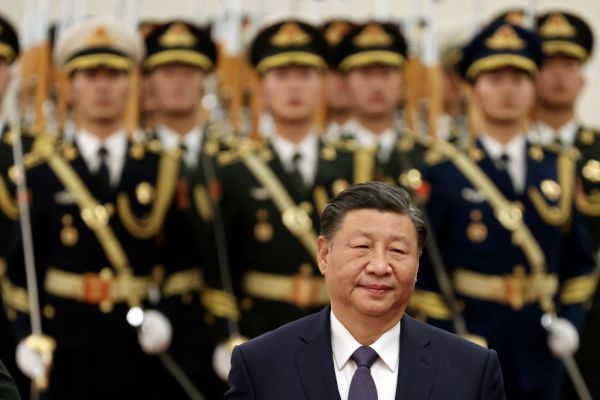

This restrained approach largely prevailed until early last decade, with the rise of Xi Jinping. That was also when a dispute over fishing rights set off a flurry of events that would reset the South China Sea board in Beijing’s favor.

China’s 2012 seizure of Scarborough Shoal, which lies just 150 miles from Manila, was unexpected, highly consequential—and a loss the Philippines could not ignore. The shoal is vital to the economic livelihood of its northern fishing communities.

When the U.S. attempted to negotiate a fair settlement only to get played by Beijing, an aggrieved and embittered Philippine government turned to the UNCLOS treaty and international law for a solution. President Benigno Aquino’s administration filed the meticulously researched Philippines v. China case at the Hague in 2013, taking aim not only at Scarborough Shoal but at Beijing’s entire South China Sea claim.

Having neither the facts nor the law on its side, China elected to reject the proceedings as “null and void.” Instead, it reasserted its position that “historic rights” give it “indisputable sovereignty” over all its South China Sea claims, and are thus beyond the reach of UNCLOS and its tribunals.

While Manila was busy with lawfare, Beijing decided to change the facts on the ground. It deployed scores of dredgers and engineers into the Spratlys to pile 4,600 acres of sand, coral, and rock atop of its occupied coral reefs, completely transforming its small outposts into large artificial islands hosting military strongholds.

By 2016, even as Manila celebrated a sweeping legal victory in Philippines v. China (though in muted fashion due to the pro-China President Rodrigo Duterte’s untimely ascent to power), Beijing had already tipped the hard-power balance. Its three new naval and air bases at Subi Reef, Fiery Cross Reef, and (adding injury to Philippine insult) Mischief Reef underscored the new reality.

While some U.S. military planners initially dismissed these bases as easy targets in any hot war, they are highly effective as power-projection platforms for China’s gray-zone operations. This campaign has included developing a huge paramilitary force—centered around a huge, purpose-built coast guard and shadowy maritime militia. It now forward-stages these forces at these bases to overwhelm smaller adversaries, occupy ever-larger spans of ocean and control access to key features, all while taking advantage of their gray-zone, non-military veneer as “law enforcement” or “fishing” vessels, respectively.

While Duterte intentionally downplayed the West Philippine Sea security dilemma in exchange for promises of economic inducements, Beijing took full advantage and consolidated its position. By the time he was succeeded by Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos in 2022, Manila’s practical options were far more limited.

Maritime occupation.

Marcos proved willing to push back, however, and this renewed Philippine feistiness has brought us to the most recent cycle of escalation. Beginning in early 2023 Manila adopted a novel new strategy—the first significant counter gray-zone innovation since its arbitration case.

This remarkable tactic of assertive transparency, led by the small but plucky Philippine Coast Guard and Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, adopted a seek-and-photograph approach that broadcast Beijing’s mendacity in vivid color for all to see. The Philippine media, kept in the dark for six years under Duterte’s policy, leapt at the chance to come along and embed on their patrols.

Initially staggered by this new approach, China reacted by dispersing its forces to make them harder to catch on camera, while trying to coax and coerce Marcos back on side. By summer 2023, however, Beijing changed tack. It pushed even more ships down to Mischief Reef and dug in for the Battle of the West Philippine Sea, Gray-Zone Edition.

Made-for-TV blockade running.

That brings us back to the beleaguered BRP Sierra Madre.

In the quarter-century since its grounding, little had been done to shore up the ship, to the extent that many wondered whether the next large storm might simply send its rusting hulk sliding into the deep. This was certainly China’s hope, as any direct assault against the still-commissioned (but utterly unseaworthy) naval vessel would necessitate U.S. involvement under its 1951 mutual defense treaty with the Philippines.

Therefore, Beijing adopted a modified blockade strategy, allowing only small, wooden resupply vessels to approach the grounded ship so that the Philippines could not bring out “construction materials” to improve the outpost—or worse, ground a second ship.

By mid-2023, the Philippines—armed with small coast guard cutters and lots of cameras—was ready to push the envelope to challenge China’s blockade.

This led to a year of increasingly alarming dramatics around Second Thomas Shoal, with growing numbers of Chinese ships intercepting every Philippine resupply mission on the high seas. Water cannons and rammings became standard fare, until a dramatic hand-to-hand confrontation took place on June 17, 2024, in which the Chinese coast guard brandished bladed weapons and a Philippine sailor lost a thumb. The following month a rickety truce was reached between the two exhausted parties, the terms of which have never been made fully public but seem to be holding up (for now).

This truce did not, however, extend to the rest of the West Philippine Sea, where clashes elsewhere began to take center stage. Repeatedly blaming U.S. instigation and Philippine provocation as pretext to escalate, China has since tightened its grip on Scarborough Shoal, clamped down for the first time on Sabina Shoal, and begun harassing fishermen around Iroquois Reef.

The strength imperative.

The incoming Trump administration will need to recognize that the perception of weakness is catnip to an expansionist power, and China has proved itself no exception to this rule. The president-elect will need to decide how to support America’s treaty ally against what has become a full-scale maritime occupation by a hostile imperial power.

Here are a few practical moves the new administration should consider to regain the long-lost initiative:

First, the new administration should announce early its intent to partner with the Philippines to jointly explore Reed Bank, where 55 trillion cubic feet of natural gas are believed to lie but which Beijing’s threats have dissuaded Manila from exploiting. The Duterte administration’s joint development project with China failed when it became clear that Beijing’s price was the weakening of Manila’s legal rights to its own resources. The U.S. has no such designs, and can make that position explicit from the beginning.

The U.S. should also make it clear that it rejects any assertion by Beijing that American movements through international waters in the South China Sea are subject to China’s veto, and that this right extends beyond its established freedom of navigation operations (FONOPS) program to include U.S. Navy and Coast Guard visits to Philippine-held outposts. Where else on the planet do we let another country tell us we can’t go visit our friends?

Specifically, the Philippines maintains a small civilian population at Thitu Island, whose beleaguered residents wake up regularly to harassing swarms of coast guard, militia, and fishing ships asserting China’s sovereignty over the island. The Trump administration can send an early signal of its support and resolve by deploying a joint U.S.-Philippine military and civic-action mission to aid Thitu’s citizens and upgrade the island’s infrastructure. Beijing can then twist itself into knots explaining how a planeload of doctors and civil engineers somehow represents a threat to peace and stability, while America makes it clear that it’s serious about protecting its investment in its treaty ally.

The U.S. should also explore adding one or two West Philippine Sea outposts to the list of nine Enhanced Defense Cooperation Activity sites we are already now jointly building out with Manila, making it clear that our mutual defense treaty extends to wherever we see a need and our ally requires our aid.

These recommendations will doubtless cause distress in Beijing as well as many regional capitals, both because they fear escalation and because some have their own competing claims. These are not risk-free moves for the U.S., but caution in the South China Sea has thus far yielded nothing but a gradual slouch toward defeat.

The U.S. has consistently arrived late to brushups in a gray-zone conflict that has been underway for decades. We have for too long clung to a paradigm that our role is merely to voice our opposition to changing the status quo and peacefully resolve disputes. Beijing has stolen several marches on us by employing a gray zone strategy for which we have had no response.

When in 2020 President Trump announced he would move America’s embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, he knew there would be hand-wringing and pearl-clutching from all the familiar places. That’s what made it a bold move, and ultimately a successful one.

The South China Sea demands no less resolve and decisiveness, before China completes its campaign of maritime occupation and area denial, and the window of opportunity for new approaches slams shut.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.