Known as one of the most prescient observers of American democracy, Alexis de Tocqueville was also keenly interested in the country’s potential devolution into tyranny. In his magnum opus Democracy in America, the 19th-century French diplomat made an important proposition: The best defense against tyranny could be found “in the circumstances and the manners of the country more than in its laws.”

By “manners” Tocqueville did not just mean social politeness, but rather the “whole moral and intellectual” attitude of the country embodied in public practice. He had in mind, in other words, virtue. Without virtuous norms people turn inward, focusing on the preservation of their own private interests. The public square grows vacant, and the state steps in to claim more and more power over our daily life. Eventually, this loss of public virtue leaves the nation a mass of atomized individuals before an all-powerful, corrupted sovereign.

If Tocqueville is right, then rebuilding public virtue is an essential work in our time, even more imperative than any transient political victories. We are becoming too comfortably cynical about politics, willing to accept that our leaders are people of weak moral fiber, and we ourselves are withdrawing from community life amid growing perceptions of disorder and insecurity. This type of moral reform, though, is far more difficult than political maneuvering. After all, moral reform is not about the exertion of power, but rather about the hard work of forming relationships and developing human souls. How do we do that?

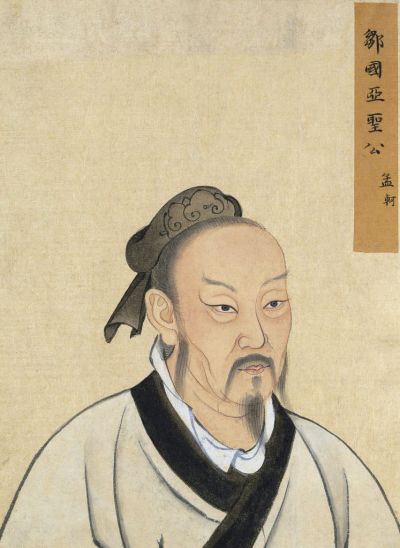

Though not as well known in the West as Tocqueville, a Chinese philosopher and public official from the fourth century B.C. might help us answer the question.

That philosopher was named Mengzi, and he lived during a crisis of public norms in his own society. Neighboring lords fought one another in constant wars of conquest and recrimination. People were engaged in violent competition for scarce goods. Historians now refer to this era, 475-221 B.C., as the Warring States period.

Known as the Second Sage, Mengzi’s influence as a thinker in Chinese history is second only to Confucius himself. As a scholar and public official, he was famous for traveling through China, attempting to persuade its lords to follow the path of benevolent government. Although largely unsuccessful in this pursuit, Mengzi gained a following in his home state of Zou, and his students compiled a book of his sayings and stories, which is known in the West today as The Mencius. Beyond these few details, little of his biography, like that of Plato in our own tradition, is certain.

But we do know that Mengzi was preoccupied with questions of virtue and moral reform. These terms might sound vague and platitudinous. It’s easy to understand winning elections and passing laws, but what would it mean to “build virtue?” Isn’t virtue just a subjective matter anyway?

Not for Mengzi, who argued that virtue had an objective grounding in human nature. All human beings, he thought, had the seeds of virtue within them: our basic moral feelings of compassion, shame, respect, and a sense of right and wrong. It is up to us to develop or negate those feelings, but all of us experience them in some way. These feelings are grounded in truths about our nature and our place in the world. There is, then, a common ground to which we can return and from which we can reason with one another.

But suppose that we really can find some common ground about virtue. Even if we could agree that honesty, integrity, fair dealing, and mutual respect are human goods, how would we go about spreading them in a society that has started to lose them? Aristotle, the great virtue-thinker of the West, thought that moral formation had to begin in childhood, that we have to be raised with the right habits in order to be virtuous as adults. But what if members of our community were not raised that way? What if virtue has decayed in parents themselves? Are we out of luck?

Mengzi didn’t think so. Why? Because the seeds of goodness remain, even if covered in bad habits. He made an effort to approach influential people and, by helping them notice their own goodness, convert them to virtue. His first method was to present to a leader the places where their moral instincts were still operative, and then to demonstrate how their other public actions contradicted their best impulses.

One famous story has Mengzi approaching one of the corrupt warrior kings of his time. He points out that the king had once taken pity on a suffering ox being led to slaughter, and set it free. Why, then, does the king nonetheless lead his people to death in senseless war? The king protests that war is a necessary evil required to expand his territory. Mengzi responded, “When a person cannot lift a feather, he is not using his strength. When someone does not rule well, he is not using his compassion.” To Mengzi, the king clearly had the resources within him to do good—if he would only notice and act consistently with them.

This, however, was not the most meaningful way by which Mengzi changed Chinese society. (Most of the rulers refused to budge.) He eventually took a different route, retiring from political life and returning home, teaching the young people there to honor and follow what was called the Way (the path of moral living in harmony with the will of Heaven). Those who were not already married to power, apparently, were easier to persuade.

Here he had much more success. With due humility, he said that a man cannot hope to solve all of the problems in his lifetime; he can only try to leave behind a good tradition. So he started one. He did this through teaching, but also through the work of expounding on the public rites of virtue. These rites were something like what Tocqueville called manners, namely, the cultural practices whereby a community expresses its moral identity to itself. Rites are practices that institute norms of what good citizenship looks like.

Passing on a tradition meant cultivating, by example and instruction, norms and practices that communicated virtue. Among these were norms about public service, which stated that, for example, if a man needs to commit even the smallest wrong for the sake of political advancement, it is better that he retire.

These norms, in time, became embodied in the Civil Service Exam, a test that any citizen pursuing public service needed to pass, which held sway for hundreds of years across all China. This was not a political science test; it was an examination of the applicant’s knowledge of the shape of a virtuous life. Of course, this did not work flawlessly, but it was a standard that held sway for centuries, and one to which people could point when their leaders fell short or violated the public trust. The tradition Mengzi affirmed became the “immutable standard” of good government against which centuries of future leaders would be judged.

The introduction of this “immutable” law did not banish tyranny and injustice from Chinese history, but it proved a resource for reform down the ages. Emperor Wang Mang cited it in the first century A.D., when he abolished slavery in all of China and redistributed land to the peasants. Scholars and philosophers frequently used it as a means of criticizing unjust power in the following centuries. In the second century A.D., Dong Zhongshu, a scholar and adviser to emperor Wu, drew from this tradition as a means of checking the king’s unlimited power, advancing the establishment of Confucian colleges that would train civic leaders in virtue. In the Middle Ages, the philosopher Zhu Xi famously took up the banner of Mengzi, criticizing a corrupt ruling class and seeking reform, even sacrificing his life for this cause. These are but a few instances of the thread of reform and virtuous influence flowing down from Mengzi through Chinese history.

Promoting public virtue will never bring about utopia, but neither is it a waste of time. The aim is not perfection; the aim is peace and the common good, and Mengzi’s example shows that virtue can go a lot farther than we think.

“Vice will always be with us. But we can choose whether vice merely haunts around the edges of our commonwealth or occupies its very heart.”

These ideas are not foreign to our own tradition. “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People,” John Adams once said in a speech to the Massachusetts militia in tones echoed by his fellow founders. “It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” In the 1840s, Abraham Lincoln, in his first-ever public speech, argued that America could not be killed from the outside, but could only “die by suicide.” Speaking against the lynching laws and rampant crime that were common at the time, Lincoln reminded the people of Illinois that if their morals were such that they no longer respected true justice and the rule of law, our nation would fall into chaos and disaster.

So, where does moral formation begin? We need to be creative about developing those public rites, those manners that Tocqueville wrote so persuasively about, those practices of public life that embody honesty, faithfulness, fairness, and integrity. In the institutions we belong to, we must be examples of these qualities. If we are in leadership, we must assert these qualities as norms. If we are not in leadership, we must hold our leaders to account. We cannot be willing to sacrifice virtue in pursuit of temporary political wins; in the long run, this poisons the soil of our common life.

All of this work begins in the heart of the citizen. Han Yu, a poet and follower of Mengzi’s Way in terms that echoed Confucius’s The Great Learning, wrote this when describing the practice of virtuous leaders:

In order to govern their country

They first rectified their own family.

To rectify their own family,

They first took heed of their own conduct.

In order to straighten their conduct,

They looked to better their hearts.

In order to better their hearts,They made straight their intentions.

By beginning with ourselves, we have the potential to initiate what Mengzi called the brilliant, transformative influence of morality. This is never a battle that is finally won. Vice will always be with us. But we can choose whether vice merely haunts around the edges of our commonwealth or occupies its very heart. So then, it is a charge given to each citizen, not to solve the world’s problems, but, where he is, simply to leave behind a good tradition.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.