Largely unnoticed by the general public on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean is a particular way America has pulled away from Europe: The average American is now vastly more affluent than the average European. The difference is not only reflected in the overall sizes of their respective economies but by the much more practical metrics of disposable income, living space, and accessibility to basic services.

Despite the overwhelming evidence, though, the idea that Americans are better off than their European counterparts is an unpopular sentiment. I casually mentioned on a recent episode of Paul Krugman’s interview show that, whereas both continents were similarly affluent a few decades ago, America is now nearly twice as rich as Europe. Cue a flood of outraged emails.

The strength of this reaction may have had something to do with Krugman’s audience, which skews progressive and American. But I’ve had similar reactions from very different audiences in the past. When I cited the same stat to a center-right member of the European Parliament a few months ago, he insisted that such stats just weren’t meaningful; in all of the metrics of life quality that truly mattered, such as disposable income and access to good housing, Europeans were surely doing at least as well as Americans. But they are not.

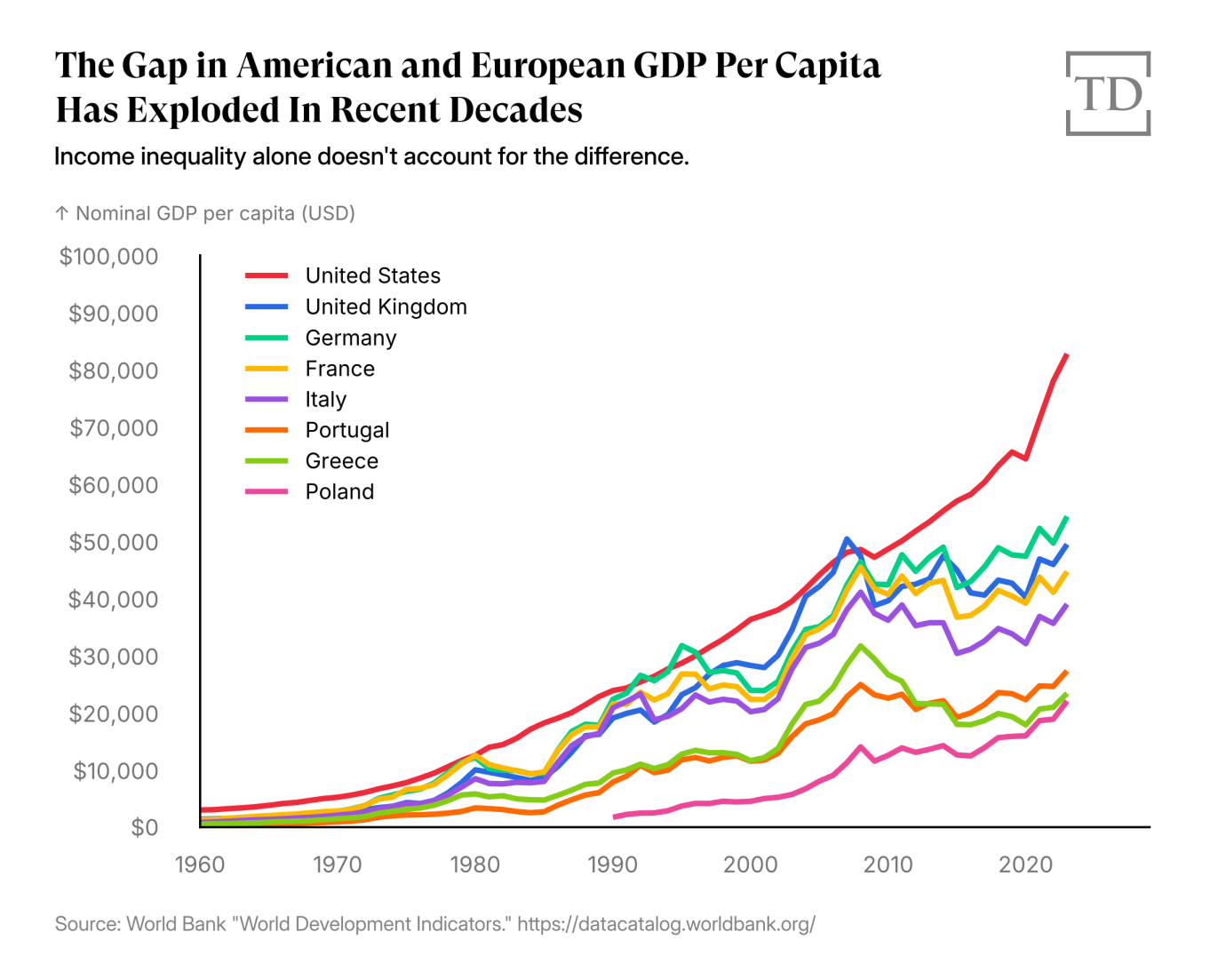

In the decades immediately before and after the turn of the millennium, the United States and the richest large countries in Europe, such as Germany and the United Kingdom, were similarly affluent. In 1995, Germany’s GDP per capita was a little higher ($32,000) than that of the United States ($29,000), with the United Kingdom lagging behind at a noticeable distance ($23,000). By 2007, at the cusp of the Great Recession, the order had slightly changed: Britain was now in the lead ($50,000), with the United States ($48,000) and Germany ($42,000) following closely behind.

Today, to an extent that few people on either continent have fully internalized, a significant economic gulf separates America and Europe. On average, Americans are now nearly twice as rich as Europeans. According to the latest available data for GDP per capita, for example, the United States now stands at $83,000, with Germany at $54,000 and the United Kingdom at $50,000, enjoying a markedly smaller income.

The contrast to less affluent European countries is even more striking. The GDPs per capita of France ($45,000), and Italy ($39,000) have fallen to about half that of the United States. Portugal ($27,000), Greece ($23,000), and Poland ($22,000) are less than one-third that of the United States.

GDP per capita is, of course, vulnerable to many of the critiques made by those who are skeptical of the great economic divergence. If America is vastly less equal than Germany or the United Kingdom, then it is indeed possible that the lion’s share of that economic pie is captured by a very small number of people; in that case, America’s greater GDP simply wouldn’t translate into notably more affluence for the average person.

The problem with this seemingly plausible explanation is that it doesn’t hold up to empirical scrutiny. America is indeed somewhat more unequal than Europe. But the difference is not nearly as stark as some people on both sides of the continent seem to assume. Indeed, the GINI coefficient (a standard metric economists use to measure inequality) for the United States, at 0.39, is only modestly higher than that of Britain, at 0.36, and only moderately higher than that of Germany, at 0.29. As a result, metrics that aren’t skewed by outsized wealth at the top, like household income at the median, still show a vast divergence between the two continents.

According to official figures for median disposable income, for example, the continents remain quite far apart. These figures aren’t influenced by outliers at the top; colloquially, we might therefore say that they represent a typical income. They also account for both the taxes that citizens pay and the transfer payments they receive from the state; they thus reflect the fact that European countries tend to redistribute more between their citizens. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the median disposable income in 2023 was $51,000 in the United States, $39,000 in Germany, and $33,000 in the United Kingdom.

That’s a lot of numbers about income. And that makes it easy to imagine, as I think a lot of skeptics about the great divergence do, that they somehow don’t translate into things that are actually important for people’s everyday lives.

Sure, this argument goes, if you make a lot less money, you might find it hard to compete for certain goods whose prices are indexed to a global market. If your heart is set on a vintage Rolex or a Ferrari supercar, much richer buyers from the United States or China might be able to price you out of the market. But when it comes to living in a nice apartment or going out to a delicious restaurant, the comparison between your wage and that of people in faraway countries matters much less; so perhaps Europeans are just as able to afford those crucial amenities.

To test this hypothesis, I tried to compile a lot of data about day-to-day material amenities. How spacious are the houses and apartments of people on each side of the Atlantic? How often can they afford to eat out or to order takeout? And what kind of digital goods can they afford to access?

Let’s start with housing. Since home prices are very expensive in the United States, many Americans might imagine that Europeans can afford to live in nicer apartments despite their nominally lower incomes. But the figures paint a different picture. The average home size in the United States is about 2,200 square feet. In Germany, it is 1,200 square feet. In the United Kingdom, it is 800 square feet. This extra space translates into all kinds of everyday amenities: Americans, for example, have about double the number of bathrooms per resident, enjoy much bigger refrigerators, and are much more likely than Europeans to have a dryer or a dishwasher in their home.

Dining out tells a similar story. The numbers are a little less exact, but estimates suggest that Americans eat out at a restaurant, have food delivered to their home, or order takeout about twice a week on average. According to a 2022 Gallup poll focusing exclusively on takeout food, for example, about 3 in 5 Americans say that they order food for pickup at least several times a month. Eating out is far less common in Europe, where there is a smaller number of restaurants per capita, and the percentage of income people are able to devote to eating out is significantly lower.

These differences in standard of living are even evident in many aspects of the digital economy. The United States and the United Kingdom both have about 80 personal computers per 100 people, for example (making this one of the rare metrics on which Britain has kept up with its former colony). But Germany has only 66 computers per 100 people, with countries like Italy (37) and Poland (17) even further behind.* The discrepancy is even more striking regarding the most basic currency of the digital age: access to the internet. According to Data Pandas, the median speed of a broadband connection in the United States is currently estimated at 280 Mbps. In Britain, it is 136 Mbps. In Germany, it is 96 Mbps.

Of course, there’s more to life than being materially rich.

Europe is a beautiful continent. Most Europeans make a perfectly comfortable living. Many are deeply embedded in thick networks of community, which benefit from a high level of mutual trust. They live in vibrant cities with beautiful buildings and a strong sense of history. There is a reason social media posts that highlight the appeal of a European lifestyle regularly go mega-viral.

Indeed, to most people—including me—many other things are far more important. As someone who grew up in Europe, I myself feel the continent’s pull. I have happily lived in England in the past, love Paris, and at least once a week fantasize about permanently moving to Italy.

It is also true that America’s economic model has significant drawbacks. Thanks to a more generous welfare state and stronger community ties, the poorest Europeans probably fare better than do the poorest Americans. And of course, there are unique annoyances and indignities that even comparatively affluent Americans suffer. For the most part, for example, I receive much better medical care in the United States than I ever have in Europe—but every time I have to deal with the insurance industry, I wonder whether the increase in quality is worth the increase in stress.

Americans have some good reasons to keep indulging their fantasies of living Under the Tuscan Sun or following in the footsteps of Emily in Paris. And Europeans can rightfully remain proud of the unique beauty found in places like Berlin or Lisbon or Siena as compared to a typical American suburb.

But it is possible to maintain this preference without denying the reality that Europe has suffered significant economic decline relative to the United States, and that this is now having serious consequences for ordinary people. Indeed, it is striking that my American friends who dream of moving to Europe usually do so because they can telework for U.S. companies or are about to retire; my European friends who dream of moving to the United States, by contrast, do so because they are frustrated by a lack of economic opportunities and recognize that they don’t have an adequate outlet for their talents.

When a development as striking as the economic divergence between Europe and America is so little known or discussed by the broader public, the reason is usually that it discomfits all kinds of other narratives. That is clearly true in this case: Europeans and Americans, the left and the right, each have reasons of their own to ignore or downplay this fact.

Europeans don’t like to recognize how far they have fallen behind the globe’s economic leaders. Meanwhile, Americans on all sides of the political spectrum have become so consumed with the negativity bias of social media that they don’t want to see any good news about their own country.

The American left is an obvious example, as it is more singularly focused on the inadequacies of the welfare state and the legacy of “structural racism.” Acknowledging that, wealth inequality and the disparity between different ethnic groups notwithstanding, the average African-American is now richer than the average European would seem like sacrilege to many progressives.

But even on the American right, many have now become convinced that the global system built by America has turned to its disadvantage. They see the country, as President Donald Trump did in his first inaugural address, as the land of American carnage, with “mothers and children trapped in poverty in our inner cities [and] rusted-out factories scattered like tombstones across the landscape of our nation.”

But for all of America’s problems, what’s truly striking about the last decades is just how successful the United States has been. As China rose and Europe’s share of global GDP cratered, America’s share held up astonishingly well. As a result, two regions that were once similarly affluent have undergone a remarkable divergence: gradually but seemingly inexorably, America has become vastly richer than Europe.

Correction, May 14, 2025: The United States and the United Kingdom both have about 80 personal computers per 100 people, not per capita as this article originally stated.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.