Economists still don’t know the full consequences of failing to raise the debt ceiling before the U.S. Treasury’s “extraordinary measures” are exhausted this summer. Though most broadly agree with Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, who said this week that defaulting on the national debt would be a “catastrophe.”

Not raising the debt ceiling also means the federal government will have to break the law somehow: Borrowing beyond the limit set by Congress (most recently in 2021) is blatantly illegal—but so is refusing to spend money Congress has appropriated.

What are other consequences of failing to raise the debt ceiling?

Less money in means less money going out.

Taxing, spending, borrowing, and paying the debt fall to Congress under Article I of the Constitution. But over the course of the 20th century, the legislative branch chose to delegate much of the power to manage the debt to the U.S. Treasury.

“Prior to World War I, debt issues were tied to particular spending,” explained George Hall, an economist at Brandeis University in Boston. “Now, there’s no connection. When the government issues a bond—is it paying for the military? Is it paying for Medicare? Is it paying for judges? It all just goes into one pot.”

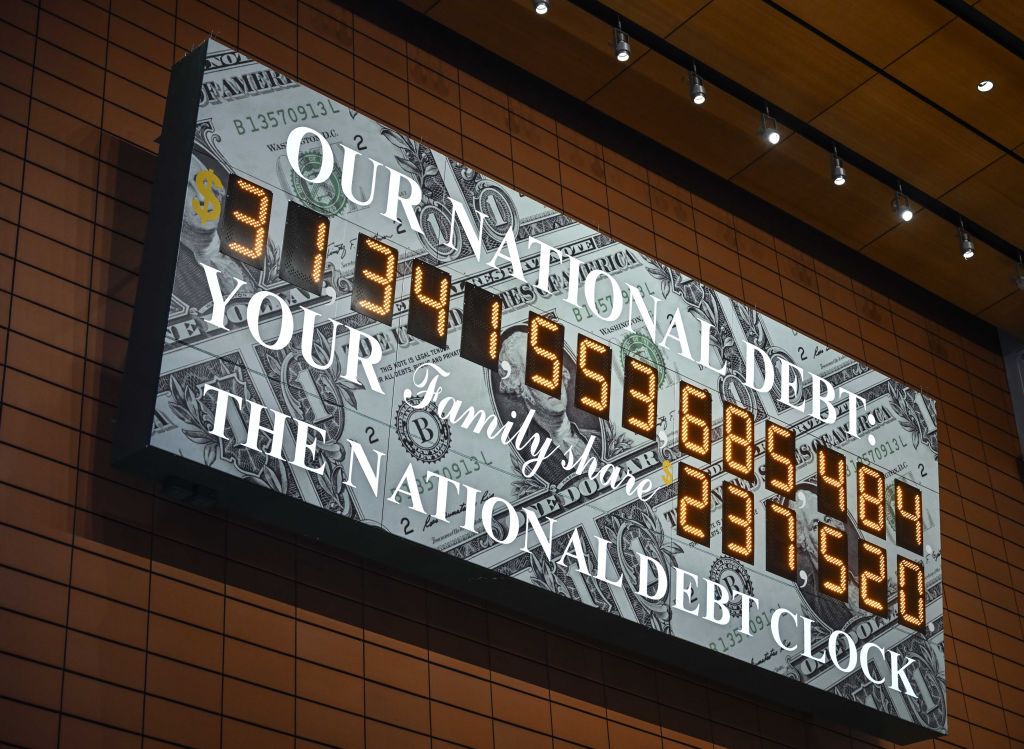

In fiscal year 2022, the federal government spent $6.27 trillion while only bringing in $4.90 trillion in revenue—a deficit of about 20 percent. The Treasury typically finances such deficit spending by going into debt, issuing bonds and other Treasury securities to the broader public (including foreign governments) and to other government agencies (such as the trust funds for Social Security, Medicare, and Transportation).

A default would cut off that borrowing spigot, forcing the executive branch to eliminate any spending that exceeds tax revenues and “balance the budget immediately,” said Brian Riedl, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

Although news coverage of government spending often focuses on annual figures reaching into the trillions, the Treasury receives deposits and withdrawals on a daily basis. If a default occurred, tax revenue would become the only source from which the Treasury could draw to pay that day’s invoices.

But the logistics for such a scenario are opaque, and Riedl noted that the “lumpy,” uneven nature of both revenue and spending could cause chaos.

“Some days you’ll have more than enough revenues come in, and other days you won’t,” said Susan Irving, a senior advisor to the comptroller general at the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

No one’s quite sure how all this could unfold, but it could create a cascade of backlogged payments.

A 2012 letter from the inspector general of the Treasury Department to the Senate Finance Committee reported on the Treasury’s contingency plans during the 2011 debt ceiling standoff.

“Treasury officials told us that it was the Department’s organizational view that the least harmful option … was to implement a delayed payment regime,” the Office of the Inspector General wrote. “In other words, no payments would be made until they could all be made on a day-by-day basis. … [P]ayment delays under such a regime would have quickly worsened each day the debt limit remained at its limit.”

Payments to individual citizens would just be the beginning since government spending is deeply enmeshed in the broader economy.

“The federal government pays hospitals and physicians for seeing Medicare and Medicaid patients,” Riedl pointed out. “They buy weapons from defense contractors; they buy office supplies from small businesses; they hire contractors to build highways. These aren’t grants. These are federal contracts where these people are legally owed money for goods and services.” Under the Prompt Payment Act, any of those parties could sue for (and likely win) the money they’re owed—plus interest, generating even more government spending. Depending on how long the crisis lasts, thousands of businesses could go bankrupt, Riedl said.

Default would roil financial markets.

A default on the government’s debt would reach further still. When the U.S. came close to the limit in 2011, financial markets were spooked, resulting in higher interest rates in the market for Treasury securities, which in turn increased the Treasury’s borrowing costs by approximately $1.3 billion for fiscal year 2011, according to GAO. That episode prompted the credit rating agency Standard and Poor’s to downgrade its rating of long-term U.S. debt.

To avoid a similar or worse scenario this year, Republicans in Congress and investors on Wall Street are pushing the idea of the Treasury prioritizing certain payments over others in the case of a default, but it’s far from clear whether such a plan is even technically feasible.

It’s possible to separate out interest payments on most Treasury securities from the rest of government spending, Irving said. “Prioritization beyond that—that is, to try and pick and choose what to pay—would require a complete reprogramming of the Treasury computers,” she said.

While some on Wall Street hope keeping interest payments flowing to bondholders would stave off a resulting financial crisis, Riedl isn’t quite convinced.

“You’re not going to fool the bond market,” he said. “They’re gonna panic just as if you had defaulted on their debt. … We don’t know what the broader macroeconomic effects are going to be in that situation, but they won’t be pretty.”

Biden’s options.

For now, President Joe Biden has said he wants a “clean” debt ceiling increase and won’t negotiate with congressional Republicans over spending cuts, and Yellen has dismissed rumblings about gimmicks—such as minting a $1 trillion coin—meant to get around the limit.

But if Congress can’t get a deal done in time, Biden could attempt to ignore the debt ceiling and keep borrowing to pay the government’s already-appropriated bills—even though the Constitution gives borrowing power to Congress, not the president. By the time any legal challenges to such a move would have wrapped up in the courts, Congress may have done its duty. Biden could even claim the 14th Amendment as justification, which states “the validity of the public debt of the United States … shall not be questioned.” (The amendment was ratified after the Civil War to ensure the reconstituted United States would shoulder the Union’s debts rather than those “incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion” by the Confederacy.)

Riedl pointed out that in 1985, then-Treasury Secretary James Baker dipped into the Social Security Trust Fund as one of his department’s “extraordinary measures” while Congress was debating the debt ceiling. Even though that action was deemed illegal after the fact, Baker didn’t face much resistance. Biden could similarly cross his fingers and hope for the best.

For now, there’s still time for Congress to come to an agreement. But complacency would be a mistake, Riedl said. “This is the main must-pass bill of 2022.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.