I was an early and enthusiastic adopter of the work-from-home lifestyle.

In 2012, my wife and I were living in a tiny one-bedroom in New York City, but we’d reached the time in our lives when we wanted to start having kids. The solution was to move to Northern Virginia, where a single-family home was in reach if we went deep enough into Fairfax County. I could work from home entirely, and we could both still access our employers’ D.C. offices. The ensuing years saw my wife increasingly work from home as well. Ultimately, we returned to our natural habitat—the Midwest—to work fully remotely, with three kids in tow.

As everyone knows, life imposes some tough trade-offs between work and one’s personal business, especially one’s family responsibilities. Working from home has made those trade-offs a lot easier, for me and many others.

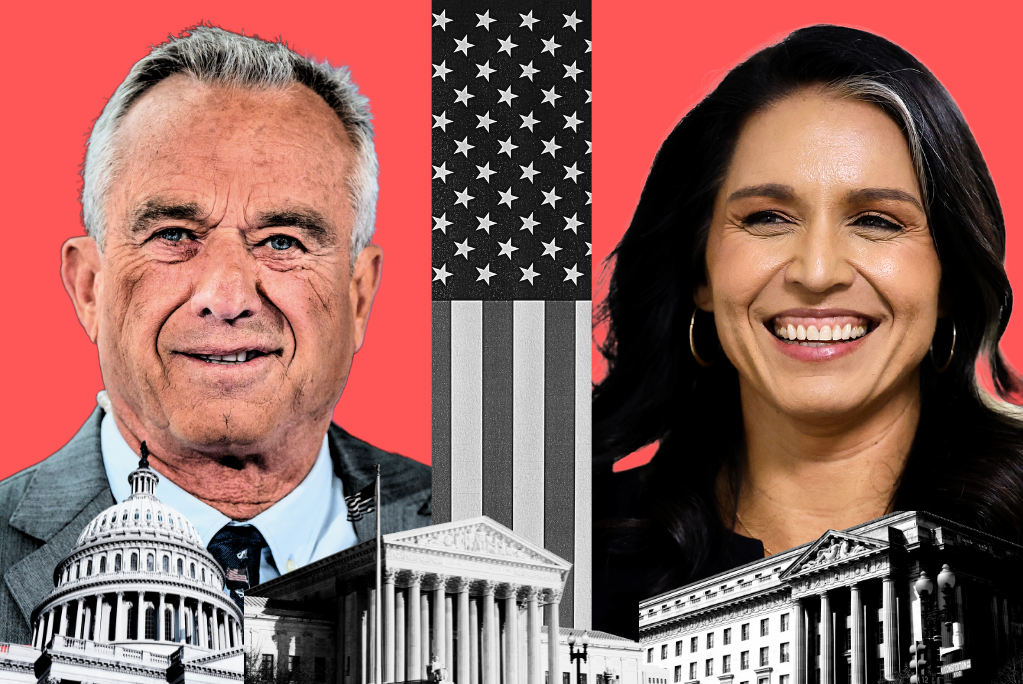

Robert VerBruggenAs everyone knows, life imposes some tough trade-offs between work and one’s personal business, especially one’s family responsibilities. Working from home has made those trade-offs a lot easier, for me and many others. … It’s little surprise that about half of parents want to work from home at least some of the time, and that parents work from home more than non-parents.

Christine RosenMore Americans report having fewer social connections, spending more time alone, and reporting higher rates of loneliness than in earlier eras. However annoying one’s colleagues can be, social interaction is good for us, and it builds camaraderie and collaboration in the context of the workplace.

America’s big cities have refused to build housing, causing prices to skyrocket—but a fully remote worker isn’t forced to buy a home in a specific place, and a hybrid worker can live farther out from the core city. In addition to bedrooms, kids require a lot of time and attention, inevitably conflicting with work priorities—but remote workers at least get to avoid the commute, which adds nearly an hour to the average work day, and we can live closer to extended family and keep working while a kid is home sick. It’s little surprise that about half of parents want to work from home at least some of the time, and that parents work from home more than non-parents.

Working from home is not the right fit for every job or every worker. But it’s an enormous boon to many, and its rise deserves to be accepted and even celebrated.

Let me be clear about two things up front.

First: I love working from home, but I don’t want the government to force the issue. I think these arrangements will flourish just fine without help from the state, and if they can’t, they should disappear.

In a free market, employers can decide whether they need workers physically present—or whether those who work from the office should be paid more—while employees can decide what jobs they are willing to take and on what terms. Government policy should allow that process to play out, although some policy decisions are unavoidable, such as government agencies’ own work-from-home rules and the question of which state(s) get to tax remote workers.

Second: There are real trade-offs involved here, as Christine Rosen ably demonstrates in her piece taking the opposing view. Like anything else in life, these arrangements are not all upside. Remote workers miss networking opportunities and in-person socialization events. Younger in-person workers can struggle to gain a foothold if their companies’ offices are desolate (or nonexistent!). The overall impact of remote work on productivity is uncertain—some analyses find a reduction in productivity, especially for fully remote workers; some say it doesn’t really matter; some even suggest it could help—but a given individual might well find he can’t focus at home or that he loses out on too many beneficial interactions with colleagues. Or, if he’s less antisocial than yours truly, he might simply get lonely.

On balance, though, the evidence suggests it’s a viable and beneficial arrangement for a healthy minority of the workforce, and particularly valuable to families.

Start with the broad trends in work-from-home, namely a gradual long-term increase that was significantly (and not just temporarily) boosted by the pandemic. Drawing on two different surveys, a recent study estimated that “the share of days worked from home rose from 5% prepandemic to 60% in the summer of 2020, fell throughout 2021 and 2022, but then stabilized at nearly 30% of days in 2023 and 2024.” A 2024 Owl Labs report found that 62 percent of U.S. workers were full-time in-office, while 11 percent were fully remote.

Clearly, a whole lot of employees, and crucially, employers as well, are finding that this arrangement makes sense for them. If people’s choices are a good measure of what they value, this is a very strong point in work-from-home’s favor.

The benefits for employees are obvious enough, including the end of commuting and an increase in autonomy. But what’s in it for employers? Well, even if there is some decline in productivity, other savings and benefits can make up for the employer’s loss. Hiring a remote worker saves on office space, allows the employer to recruit far more broadly, and may improve employee retention.

Further, the benefits to employees can redound to the benefit of employers. Working from home is a valuable thing to offer: Studies indicate a willingness to take a pay cut of up to 25 percent to work from home, so these positions can give companies the opportunity to offer or negotiate lower pay, or to attract candidates who otherwise would think the pay is too low. Speaking personally, I am most certainly not taking my kids out of their schools to buy overpriced real estate in a big city to take a new job, and I’m willing to accept that means some limits on the positions and salaries available to me.

Remote work has broader societal impacts as well, which are worth discussing even if I ultimately believe that individual, free-market decision-making should decide the issue. The biggest potential upsides, in my view, could be an increase in our floundering fertility rate, coupled with parents spending more time with their kids.

As for a fertility boost, the commonsense mechanism is that by giving parents more time and more freedom in where to live, working from home could make it easier for workers to have more kids. Research on this effect is preliminary and a little conflicting, but generally supportive, at this point. A study from the Economic Innovation Group (EIG) suggests that remote workers are more likely to marry, and that working from home appears correlated with pregnancy intentions and, for some subsets of women, fertility as well. Further, a German study found that the rollout of broadband internet led to an increase in women working part-time or from home, and in turn to an increase in fertility.

Even if parents don’t have more kids, they will likely spend more time with the ones they have if they’re commuting less. One study found that work-from-home employees spend about a tenth of the time they save on caregiving, with parents, naturally, spending more than that. EIG’s research similarly found an increase in child care among those who work from home.

The ongoing popularity of working from home can also reshape big cities. Trade-offs being inevitable, the downsides of these shifts could include less in-person interaction and a decline in business in dense downtown areas.

The big benefits, though, include reducing housing pressure on those extremely expensive areas, both by dispersing population outward a little and by encouraging the conversion of office space to housing. One study found that while city cores lost significant population in the years following the pandemic, folks generally went to the city fringes or suburbs—a pattern experts call a “donut” effect, to the consternation of copyeditors—rather than leaving the area entirely. Those who did leave generally went to smaller cities rather than rural areas, so we’re not talking about the demise of urban America, just a gentle shift away from places that have refused to build enough housing to meet demand. Reduced commuting can also bring down traffic congestion at peak times.

Opposing Debate

Further, increased telework could help the environment. Yes, pushing people toward the suburbs can lead to increased non-commute driving in some cases—heck, if I still lived in Manhattan, I might not even own a car. But most teleworkers don’t make such drastic location shifts, and the reduction in commuting, combined with the reduced need for office space, is enormous. A 2023 study finds that “switching from working onsite to working from home can reduce up to 58% of work’s carbon footprint.”

Looking to the future, one last point is worth making: It’s not clear how the rise of AI will affect working from home, and I view this new technology as one of the biggest risks. On the one hand, workers who use AI as a tool can certainly do so from home. On the other, jobs that can be done remotely are often those where a worker sits at a computer and carries out tasks in the digital realm, which are precisely the types of jobs AI can increasingly do by itself. In the viral story “AI 2027,” a sci-fi-style prediction from a group of AI forecasters, “25% of remote-work jobs that existed in 2024 are done by AI” in October of 2027, “but AI has also created some new jobs, and economists remain split on its effects.”

AI could replace these jobs even if the current workers were still in the office, of course. But if the more aggressive predictions pan out, those thrown out of work may regret moving away from dense city cores with lots of other opportunities. If AI starts writing think-tank reports and articles like this one, perhaps I’ll soon wish I’d never left Northern Virginia, or even New York.

We’ll deal with that in 2027 if it happens, I guess. But for the time being, countless remote workers have found this arrangement a fitting solution for so many of life’s problems, from lengthy commutes, to high housing prices, to family obligations that conflict with work. It’s a positive development and an enormous help to parents in particular.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.