Yesterday a passage in Niall Ferguson’s new column brought me up short. Ferguson was ruminating on the causes of America’s mental health crisis and found himself unsatisfied with the usual explanations—pandemic isolation, substance abuse, despair at the culture’s recurring failure to solve problems like mass shootings that everyone agrees are horrific. Bad vibes aren’t a simple case of individuals reacting similarly yet independently to different stressors, Ferguson reasoned. They’re infectious.

It’s a contagion.

Contagion is the key concept if we are to understand our modern malaise, and you cannot understand contagion until you understand the structure of networks. In my 2017 book The Square and the Tower, I quoted Stanford University biology professor Deborah M. Gordon’s argument that online social networks were replicating on a vast scale many of the more insidious features of friendship circles among girls in a middle school. Malicious gossip spreads far faster and further on Facebook than it ever did in the schoolyard.

…

[The theory that social media makes you feel worse] has since been reinforced by studies such as Allcott et al. (2020), which concluded that using social media was a form of addictive behavior. The issue remains a battleground for social scientists, but I remain firmly persuaded that the creation of vast online networks greatly increased our vulnerability to contagions of the mind, including conspiracy theories and “mind viruses” of all kinds.

“Contagions of the mind.” I read those words and thought, naturally, of Dilbert.

If you’re not Very Online, you know Scott Adams as the creator of the popular comic strip about office culture. It’s been syndicated for more than 30 years and has made him a rich man. If you are Very Online, you know Adams as a red-pilled influencer who’s grown prominent in right-wing social media since Donald Trump entered politics in 2015. Last week, during a YouTube livestream, he mused about the findings of a (questionable) Rasmussen poll on race relations in which only a slim majority of black Americans agreed with the sentiment “It’s okay to be white.” At long last, the Very Online version of himself caught up to the not Very Online one.

“If nearly half of all blacks are not okay with white people … that’s a hate group,” he told his YouTube audience. “I don’t want to have anything to do with them. And I would say, based on the current way things are going, the best advice I would give to white people is to get the hell away from black people … because there is no fixing this.” You can guess what happened next. He was duly defended by certain other red-pilled influencers better known for their not Very Online successes, replete with grumbling about “cancel culture,” but the writer Thomas Chatterton Williams dealt with that complaint elegantly. When we think of “cancel culture,” he said, we think of people being ostracized for violating social norms that haven’t been broadly agreed upon. That’s not what Adams did. Advising white people to “get the hell away from black people” has been pretty well settled as Bad for, oh, 50 to 60 years.

His lapse in judgment was so glaring, and the financial consequences so dire, that I think his rant can be explained only as a form of the “contagion” Ferguson described. Removed from the online feedback loop in which he’s immersed himself, Scott Adams likely wouldn’t have been caught dead riffing in public on the virtues of voluntary racial segregation. But once he was conditioned by his social-media subculture to normalize red-pilled “truths” that the wider culture disdains, he lost perspective. The mentality of the edgelord network he cultivates on Twitter brought him to ruin.

It may be the single most self-destructive case of Internet brain-poisoning I’ve ever seen. Wait, no: the second-most.

There are many such “mind viruses” circulating nowadays that impair otherwise rational people’s better judgment, not just the “woke” strain that the world’s richest troll likes to complain about. As with biological viruses, it must be the case that some people are more vulnerable to contagions than others. A new post by Matt Yglesias that’s circulating today wonders whether entire ideologies—or at least the way they’re currently practiced—might be more susceptible to unhealthy modes of thinking.

Twenty years ago, when America was consumed by the threat from terrorism, “indoctrination” and “radicalization” were the terms of choice to describe how toxic online networks attracted recruits and influenced their thinking. Nowadays, post-COVID, we tend to favor the language of contagion. When the Center for Strategic and International Studies published its report on QAnon in 2020, for instance, it borrowed terms from infectious disease (“no one is immune”) to describe the movement’s “spread.”

Yglesias’ post is about an especially dangerous contagion. Depression keeps rising among American teenagers, particularly teenage girls, and the trend has been in motion for roughly a decade. A popular theory as to why comes from Jonathan Haidt, who points the finger at social media. As teenagers’ social lives moved from the real world onto online platforms, Haidt reasons, their mental health began to suffer. They grew more isolated; they were exposed relentlessly to unrealistic beauty and lifestyle standards; the petty snubs and name-calling that otherwise wouldn’t escape a school hallway now go live to the whole world on Snapchat and Instagram, where they’ll remain for eternity.

Haidt’s thesis is compelling, but Yglesias notes a study that complicates it. When you measure kids for “depressive affect,” it turns out that liberals of both genders score higher than conservatives of both genders. Liberal boys are much more likely to present a “depressive affect” than conservative girls are, in fact. His theory is that adult leftists have gone too far in treating despair as evidence of one’s progressive bona fides and that their attitude has begun to, well, infect younger leftists.

Some of it might be selection effect, with progressive politics becoming a more congenial home for people who are miserable. But I think some of it is poor behavior by adult progressives, many of whom now valorize depressive affect as a sign of political commitment.

…

For a very wide range of problems, part of helping people get out of their trap is teaching them not to catastrophize. People who are paralyzed by anxiety or depression or who are lashing out with rage aren’t usually totally untethered from reality. They are worried or sad or angry about real things. But instead of changing the things they can change and seeking the grace to accept the things they can’t, they’re dwelling unproductively as problems fester.

If you’re not chronically glum and borderline suicidal about the lack of progress on climate change and gun control and abortion rights and ending the damned filibuster, can you truly say that you care?

There may be something to that—emphasis on “may.” If it turns out for whatever reason that liberal teens are more likely to use social media than conservative ones are, and if Haidt is right that social media is driving teen depression, we’d expect to see more “depressive affect” in left-leaning kids even if adult progressives weren’t treating depression as some kind of virtue.

It could also be that the content on social media is more tailored to exacerbating left-wing fears than right-wing ones. I don’t use TikTok, but it wouldn’t surprise me if conscientious teen content-makers are more prone to worrying that climate change or school shootings will kill us all than that, say, Antifa will. Your average conservative teen will roll their eyes at catastrophism in that vein, but a more progressive teen will take it to heart.

Or, perhaps, social conservatives are right that the wellness gap between liberal and conservative kids is real but that Yglesias has misdiagnosed the cause. Young conservatives are more likely to live in religious households and therefore to have an identity and social network distinct from what Instagram provides them. Liberal teens, by contrast, are encouraged to fashion their identities whole cloth, up to and including their genders. That’s a heavy burden to carry in one’s formative years.

Still, there are some curious elements to liberal doomsaying that support Yglesias’ idea about “depressive affect” being incentivized.

For instance, I can’t count the number of news stories I’ve read in the past five years quoting liberals who believe it’s irresponsible to have children in a world where the planet continues to warm inexorably. Yglesias is right too to point out how often progressives resort to therapy-speak about “harm,” “danger,” and “violence” when confronted by certain perspectives that offend them. In his column, Ferguson recalls that the daughter of a friend felt obliged to transfer out of a prestigious U.S. university because she couldn’t take the psychobabble about victimization from her peers anymore. When she told them that she felt well-adjusted, they replied, “Ah, your trauma must be really deeply buried.”

If you’re encouraged to feel wounded or traumatized not just by your own personal misfortunes but by all the world’s injustices, I dare say your mood might suffer for it. Yglesias’ advice to liberals: Stop catastrophizing! You’re making yourself sick.

It’s good advice. But conservatives do plenty of catastrophizing too.

They catastrophize about different things. Many are convinced that America’s elections are rigged and that the country is being run by a hostile, unelected “deep state.” Most believe crime is out of control (despite the fact that violent crime hasn’t risen since the start of the pandemic) and that one-world liberals in the Democratic Party have made a deliberate shambles of the border in hopes of replacing America’s population with Mexico’s. They know that the media is biased against them and routinely connives to suppress the truth, never mind what the right’s own media does. And they’re sure that the country was victimized by a Chinese bioweapon—which they also claim was “just the flu,” oddly—and that the bioweapon was later used as a pretext by evil bureaucrats to inject an unsuspecting population with a vaccine containing God knows what.

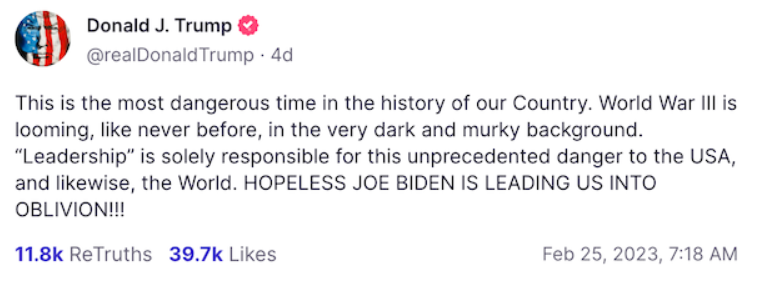

On her worst, gloomiest day, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has never expressed thoughts about America and the future as dire as those routinely expressed by the alarmist, power-hungry psycho that leads the American right:

Nationalist retail politics is little more than absurd catastrophism about being “attacked” on all fronts paired with the promise that all can magically be made right by electing a sufficiently ruthless messianic nationalist. Another recent Trump post distilled the pitch to its essence: “Our Country is under attack by the Fake News Media, CRIME, and an INVASION at our Southern Border. WE MUST TAKE BACK THE WHITE HOUSE IN 2024, AND MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN!”

The Victim Olympics between left and right is plenty competitive.

None of which contradicts Yglesias, though. He didn’t claim that Democrats do more catastrophizing than Republicans, just that they’re conditioned to react to catastrophe in a particular way, by evincing depression and paralysis. But assuming he’s right, one wonders: Given that rage and combativeness rather than depressive affect are valorized by right-wing populists as the proper response to catastrophe, how are young right-wingers being conditioned to behave as adults when they feel frustrated by setbacks to their agenda?

What sort of contagion might color the next generation of American politics?

One thing that fascinates me about the idea of a paralyzed, depressive left and an angry, aggressive right is how it confounds traditional stereotypes about liberals and conservatives. Liberals are proactive utopian social engineers convinced they’ll achieve capital-P Progress incrementally over time; from FDR to LBJ to the DSA, the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward the Green New Deal or whatever. Conservatives fear that each lurch toward “Progress” brings new difficulties and unintended consequences and view their mission as fundamentally reactive, to block the left’s ill-advised tinkering. They stand athwart history yelling “stop,” to borrow a phrase.

Liberals believe they can change the world and human nature, conservatives are resigned to the fact that those things are what they are. But if Yglesias is right, young left-wingers are being conditioned by their elders to treat gloomy resignation as a sort of political virtue—and meanwhile, young right-wingers are being conditioned by the likes of Ron DeSantis and the U.S. Supreme Court to believe that previously unthinkable culture-war gains are possible if you take the initiative and refuse to back down. A lot more goes into political outcomes than having the “right attitude,” of course, but attitude must count for something. A depressive left and a proactive right seems like a recipe for right-wing victories.

It might also be a recipe over time for a turnabout on which party is more patriotic. Because the left traditionally has concerned itself with addressing America’s injustices, real and perceived, while the right has concerned itself with resisting left-wing social engineering, patriotism has come more easily to the latter. Republicans love the country as-is, Democrats love what the country might be if they get their way. In a country where the left is depressive and reactive and the right is proactive and nationalist, that could shift. Once liberals are maneuvered into defending the status quo from nationalist social engineering, the former will feel more inclined to celebrate the America that exists and the latter more inclined to celebrate the America of their imaginations.

Perhaps that shift has begun already. It was a Democratic president, not a Republican one, who declared in the thick of the 2016 campaign that “America is already great.” It’s a Republican congresswoman, not a Democratic one, who’s lately taken up “national divorce” as her pet cause, blamed America for Russia’s misfortunes abroad, and called for a “safe space” for her ideology.

The guy responsible for the tweet below sits on the board of trustees of a public university. If you didn’t know his politics, would you guess that he’s of the left or right based on his ambitions to cultivate a student body that’s more aligned with his “mission”?

A lot of realignment will happen in the years ahead if the right becomes the faction of can-do social engineers and the left becomes the faction of cautious preservationists. It might even generate a vicious circle for progressives in which, as the nationalist agenda advances, they become more depressed and resign themselves to an agenda that seeks merely to limit Republican gains instead of achieving Democratic ones. Take it from a conservative: Once you adopt the mindset that policy initiatives are the province of the other side, that there’s a “one-way ratchet” and your highest ambition is simply to slow its turning, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Then again, if the left was as passive and paralyzed as all that, the post-Roe 2022 midterms would have gone a bit differently, no?

The realignment should be fascinating, if nothing else. Case in point: At last check, Scott Adams was reassuring fans on Twitter that he’s been discriminated against by whites and that he, er, identified as black for several years. “White people suck,” he apparently told his audience on his latest YouTube livestream, leaving one to wonder if maybe white people should get the hell away from Scott Adams. As both sides of the American political spectrum continue to immiserate themselves in catastrophism, the contagions are going to get very, very weird. I’m excited to be trapped in this pandemic with you!

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.