Dear Capitolisters,

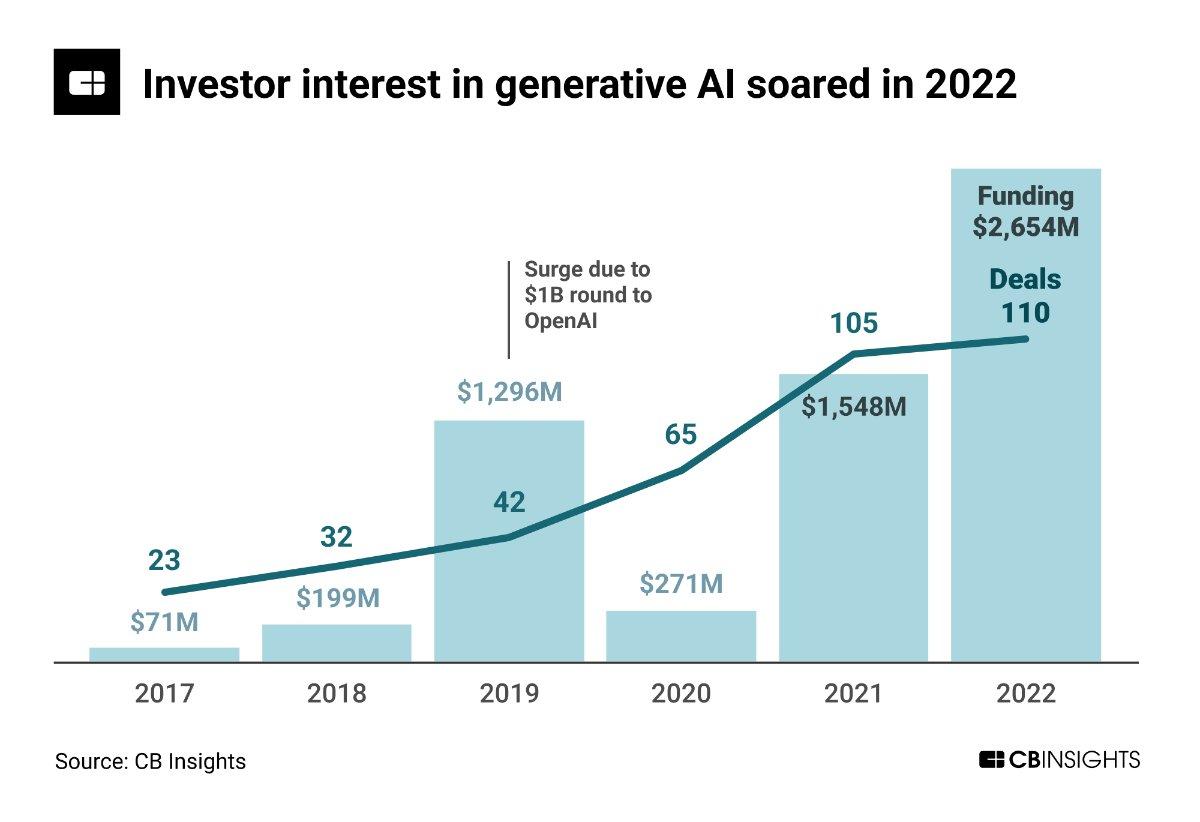

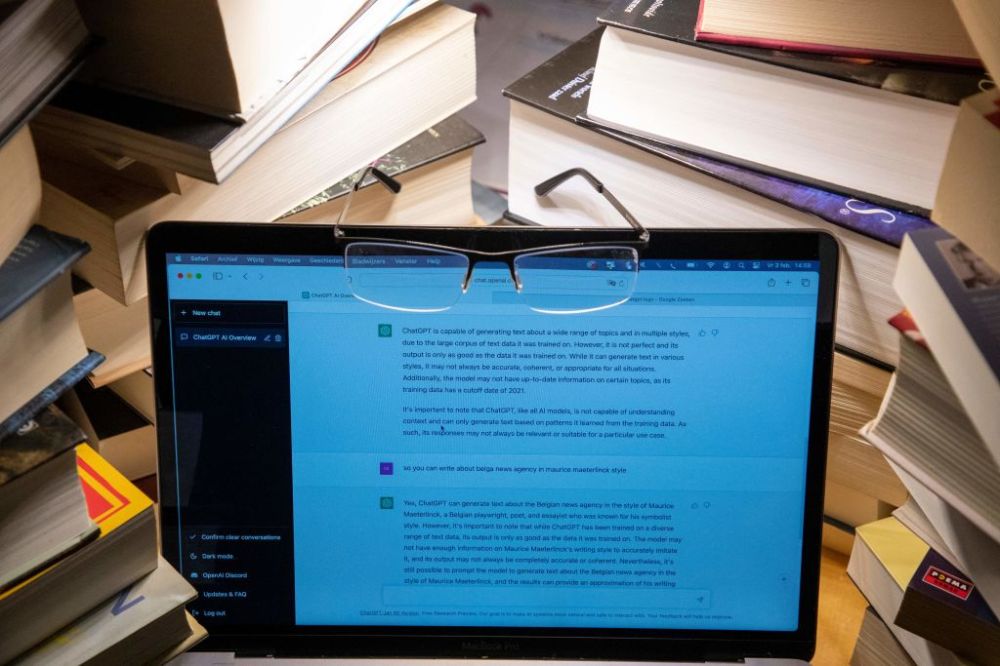

For a few minutes every Friday, I’ve been playing around with ChatGPT, the widely discussed “generative artificial intelligence” chatbot that can—after a few good human prompts—produce some pretty impressive writing about almost anything. If you haven’t tried ChatGPT yet, I highly recommend that you do; it’s easy and fun. My initial impressions of it and the other new AI products I’ve seen—for writing, art, coding, and other tasks—are that they’re still quite raw but clearly hold tremendous long-term potential for improving, if not revolutionizing, many aspects of our lives. And, judging by the explosion of investor interest in generative AI, including Microsoft’s massive bet on ChatGPT and the multitude of similar products coming down the pipe (here’s Google’s), I’m definitely not alone.

Accompanying this techno-optimism, however, has been a litany of concerns about the job-destroying potential of ChatGPT and other generative AIs. CBS News, for example, provides a handy list of the jobs “most likely to be replaced by chatbots like ChatGPT.” Others are worried about “mass unemployment,” “destabilizing white collar jobs,” or even a global AI “MegaThreat.” One recent columnist warned that “Artificial intelligence is not only coming for your job but will have a hand in laying you off, too.” And even more level-headed commenters, while recognizing the current technology’s limitations, warn that it will evolve rapidly and thus displace millions—just not today.

Tomorrow, on the other hand…

As you can probably guess, I’m more sanguine about the job-destroying effects of ChatGPT and its AI brethren—not because I doubt the tech or its potential, but instead because of humanity’s and the U.S. economy’s long history of overcoming disruptive technologies that were supposedly going to put us all out of work.

Endless (and Fruitless) Worries About Techno-Unemployment

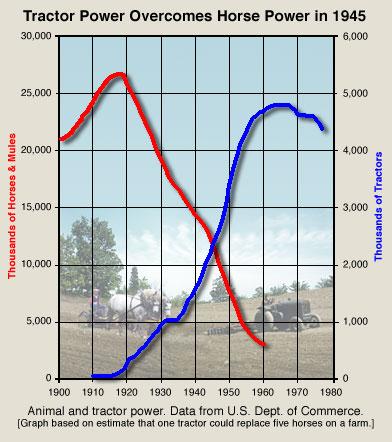

There’s little doubt that new technologies can and have displaced certain work tasks in the past. Consider, for example, this great chart from UC-Davis’ Aaron Smith showing how tractors caused an 85 percent reduction in farm horses between 1920 and 1960:

As cars, trucks, and other mechanized contraptions replaced workhorses in other parts of the U.S. economy, almost all of them moved out of the workforce and on to greener pastures (ha), never to work again.

Humans, on the other hand, are still working—even as the endless march of disruptive technology has destroyed all sorts of occupations, horse-related or otherwise, over the centuries. (Here’s a short list.) That’s because, as Smith notes, “[u]nlike draft horses, people are adaptable.”

This adaptation lies at the core of a classic economic fallacy called the “Lump of Labor,” which the St. Louis Fed’s Scott Wolla describes and debunks in a recent essay (emphasis mine):

The lump of labor fallacy is the assumption that there is a fixed amount of work to be done. If this were true, new jobs could not be generated, just redistributed. Those who believe the fallacy have often felt threatened by new technology or the entrance of new people into the labor force. These fears are rooted in a mistaken zero-sum view of the economy, which holds that when someone gains in a transaction, someone else loses. It's a tempting idea to some because it seems to be true. For example, jobs can be lost to automation and immigration. However, that is not the full story. In reality, the demand for labor is not fixed. Changes in one industry can be offset, or overshadowed, by growth in another. And as the labor force grows, total employment increases too.

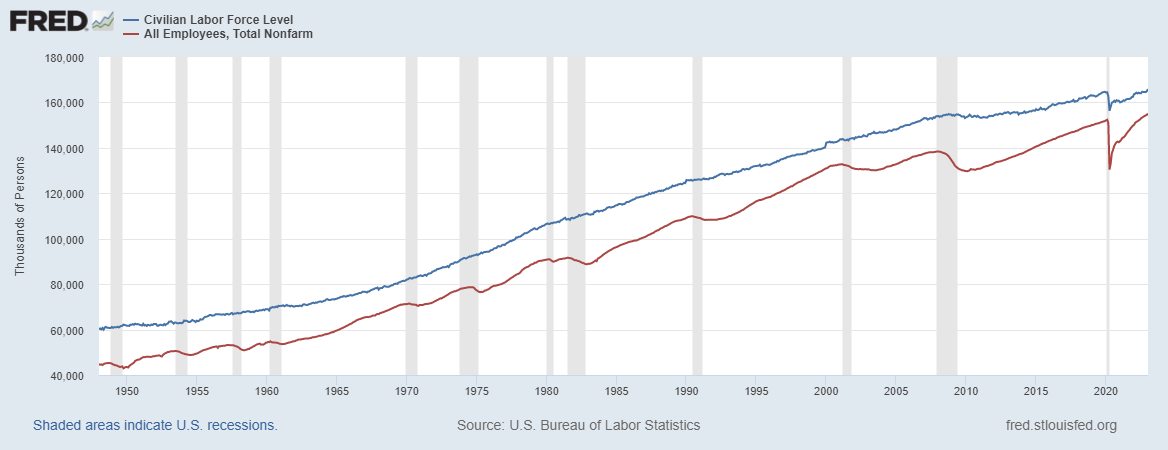

As Wolla then shows, the U.S. workforce and total number of jobs have consistently expanded over decades, despite numerous economic shocks—a testament to humans’ ability to adapt over time to whatever comes our way.

This includes radical changes in technology that at the time raised widespread fears of mass unemployment. Such fears, of course, date back centuries, even earlier than the famous Luddite weavers destroying the early 19th century textile machines (and whole factories) that threatened their jobs and lifestyles. Yet research consistently shows that, while technology can and does displace some types of jobs, as well as some tasks at the jobs that aren’t destroyed entirely, fears of jobless hordes simply haven’t materialized.

Instead, humans—and markets—adjust in two ways.

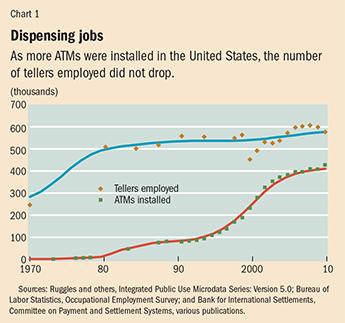

First, we learn to use whatever new technology comes along, so that it complements our work instead of consuming it. One of the more famous and commonly cited examples of this phenomenon is ATMs, which many predicted would make bank tellers obsolete. Yet, as Boston University’s James Bessen showed in a great 2015 paper, the rapid deployment of ATMs in the 1980s and 90s actually coincided with a small increase in U.S. bank teller employment over the same period:

He cites two reasons for this surprising result, each of which shows how humans and markets react to new technologies in unexpected ways:

First, ATMs increased the demand for tellers because they reduced the cost of operating a bank branch. Thanks to the ATM, the number of tellers required to operate a branch office in the average urban market fell from 20 to 13 between 1988 and 2004. But banks responded by opening more branches to compete for greater market share. Bank branches in urban areas increased 43 percent. Fewer tellers were required for each branch, but more branches meant that teller jobs did not disappear.

Second, while ATMs automated some tasks, the remaining tasks that were not automated became more valuable. As banks pushed to increase their market shares, tellers became an important part of the “relationship banking team.” Many bank customers’ needs cannot be handled by machines—particularly small business customers’. Tellers who form a personal relationship with these customers can help sell them on high-margin financial services and products. The skills of the teller changed: cash handling became less important and human interaction more important.

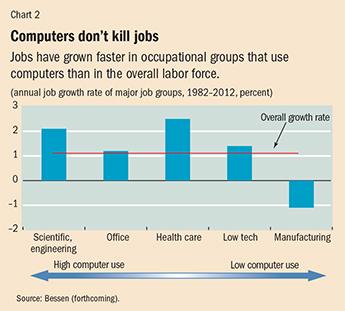

In a subsequent paper, Bessen looked at the proliferation of computers since the 1980s and found similar effects. In fact, employment in occupations that used computers grew faster, not slower, than ones “protected” from this supposedly job-killing technology. Even highly routine and middle-wage occupations—jobs more likely to be destroyed—increased in these industries. It was only the lowest-skill jobs that shrunk.

Again, adaptation is key here: Bessen finds that computer automation of an occupation likely increased demand for that occupation; thus, even as computers allowed more work to be done with fewer workers, there was even more work to be done so overall employment modestly expanded in the industries examined. He also finds evidence of job-churn, as workers in a certain occupation gained new computer-related skills (or were replaced by ones with those skills). He importantly adds that, “If labor markets were not flexible, [then] the implied job transitions might indeed create unemployment. But that is not what appears to be happening in the US at least.” Huzzah.

Other research shows that this adaptation isn’t isolated to the United States. Economist Ian Stewart and his colleagues, for example, looked at centuries of U.K. census data and found that “many of the fields most transformed by technology have produced the biggest increases in employment, from medicine to management consulting,” because “machines and people were highly complementary,” with the latter learning to use the former (and thus remain employed).

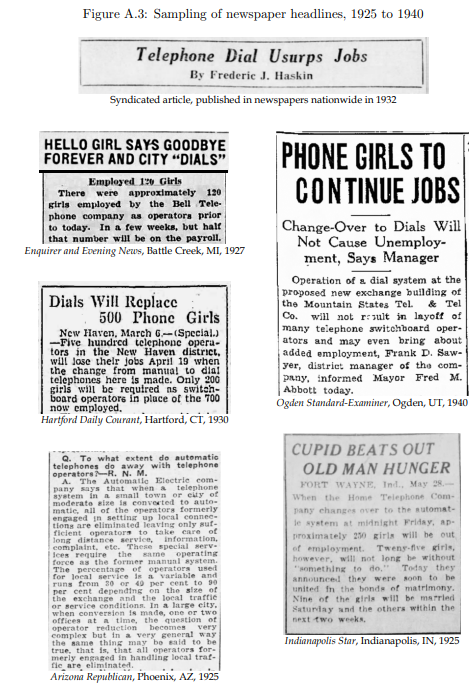

Of course, not every occupation survives the proliferation of a new technology, but this gets to the second reason why mass unemployment never arrives: Workers adjust by moving into other occupations and industries that are more in demand. One of my favorite recent papers on this phenomenon looks at telephone operators, who represented a significant chunk of the female workforce in the 1920s (2 percent, which would be around 1.5 million women today) and experienced arguably the biggest automation shock in U.S. history when machines quickly took over their duties in the 1930s and 40s. In fact, “telephone operator” was the fifth largest occupation in the country for young American women back then, and its numbers permanently declined by as much as 80 percent immediately after a town was “cut over” to mechanical switching. Thus, people back then were very concerned about the sudden unemployment of tens of thousands of young women because of those newfangled rotary dial phones:

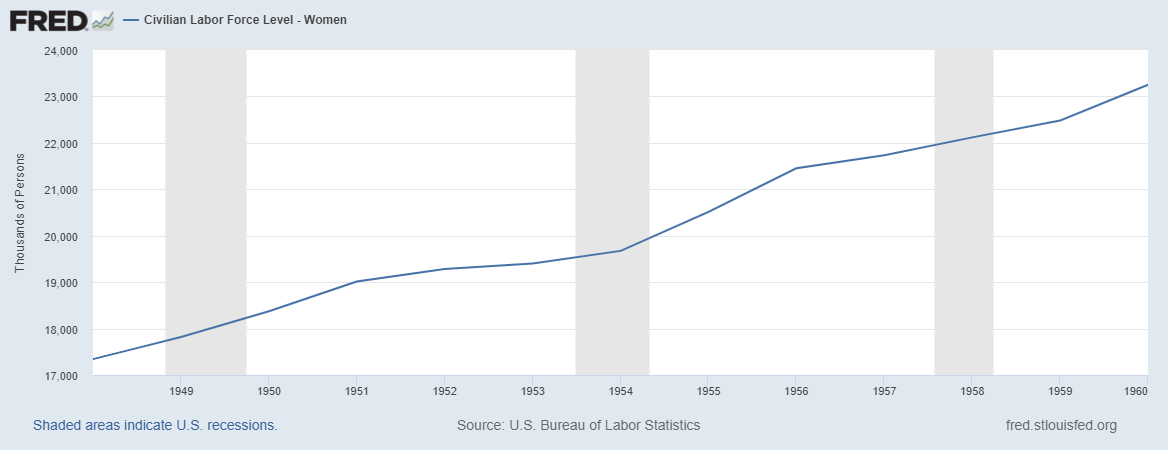

Once again, however, this massive and rapid “telephone shock” didn’t cause widespread unemployment among young women because they, and the market, adjusted: “The negative shock to telephone operator demand was instead counteracted by growth in other occupations, especially secretarial work and restaurant work, which absorbed the women who might have otherwise been telephone operators.” In other words, young women who would’ve become telephone operators got other jobs, and female employment continued to rise throughout the period:

As with computers, not everyone came out ahead from telephone modernization. In particular, the authors show that some incumbent telephone operators—especially older ones with more invested in their current occupation—did drop out of the workforce or find work at lower pay. Overall, however, the relatively massive “telephone shock” barely registered a blip in the U.S. economy. The authors thus conclude:

Local economies can adjust to large automation shocks over relatively short horizons and continue to absorb the steady stream of young workers entering the labor market, when countervailing labor demand develops to take advantage of the newly abundant factor, in activities where that labor has comparative advantage. In the 1920s and 1930s, much like now, contemporaries feared these opportunities were gone and never coming back—but those fears proved to be misplaced, as other jobs grew to take their place.

The reallocation of labor—a scarce resource—from one industry or occupation to another can surely be disruptive for some, but it’s good and important for the economy over the long term: As we’ve seen in agriculture, manufacturing, and some services, workers whose jobs have been “taken” by tractors, industrial robots, rotary phones, computers, and other technologies move into other occupations or industries that need previously unavailable workers. So, we end up getting the mechanized output and the displaced workers’ new output, and we thus end up richer than before that technology existed (i.e., back when we had to choose between the two products).

We’ll (Probably) Adjust Here, Too

We see both types of adaptation in (admittedly) early assessments of generative AI. As Noah Smith and pseudonymous AI researcher “roon” detail in a recent article, for most jobs and workers the current technology will likely complement our work, rather than replace it (and us). They run through several examples of how this could work in practice—for writing, law, art, industrial design, and so on—and in each case explain how workers will learn to use generative AI and adopt a “sandwich” workflow:

This is a three-step process. First, a human has a creative impulse, and gives the AI a prompt. The AI then generates a menu of options. The human then chooses an option, edits it, and adds any touches they like.

This is basically the workflow I’ve stumbled into when playing with ChatGPT for the last few weeks: I have an idea for an essay; I ask it to write a first draft, with specific instructions regarding style and content; I ask it to refine that draft to correct, remove, or supplement the findings or to add things like citations and numbers; I do this a couple more times; and it ends up producing a sorta-useable first draft of something I might eventually be able to turn into a Cato blog post (though I haven’t actually gotten to that final stage—yet). I expect that, eventually, this will be a common workflow for writers and wonks, but certainly not yet and certainly not for relatively novel issues that lack an already-developed base of scholarly research and writing. And, to the extent that this technology does end up producing decent blog content, it’ll free up more time for me to do things like podcasts and speaking events, for which there is no robotic equivalent.

So, my job is probably safe—for now—but I’m going to need to adapt. And plenty of others will too. But, assuming AI doesn’t evolve far more quickly than most expect, we’ll generally be fine (though work will be different than it is today).

Other jobs, however, probably won’t be so lucky. It’s almost certainly true, for example, that generative AI will soon eliminate lower-skill “knowledge” jobs that entail little more than creating basic digital goods and services (e.g., customer service, newswire summaries, or clipart). As anyone who’s recently complained to an online customer service chat, this displacement has already been happening, and AI will surely accelerate the trend. Workers performing the remaining tasks will thus need to upskill to more creative work or to look for work in other, lower-skill industries where generative AI isn’t a capable replacement.

Changing jobs is never easy, but, as Wolla notes, the changers should eventually find new and different “jobs” because, in a free economy, new occupations and industries always emerge when others disappear:

So, what guarantees that if one industry declines, others will grow? The answer is human wants—which are infinite. Indeed, many of the goods that we spend our money on now did not exist a century or even a few decades ago. And, many of the industries in which many people work today didn't exist a century ago.

As long as this process continues, mass unemployment isn’t on the horizon. Humans aren’t horses; we can and will change—and the market will too.

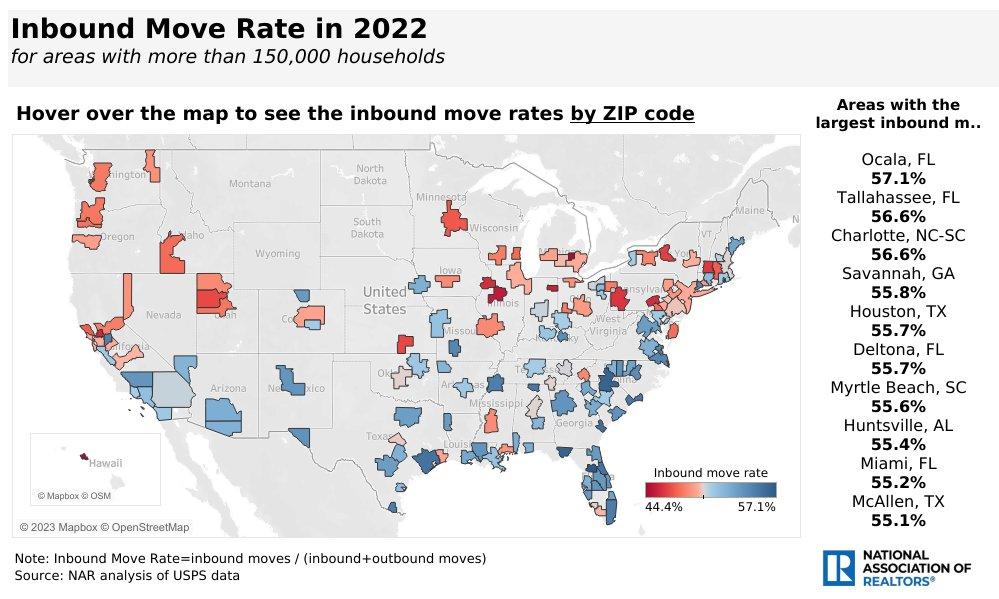

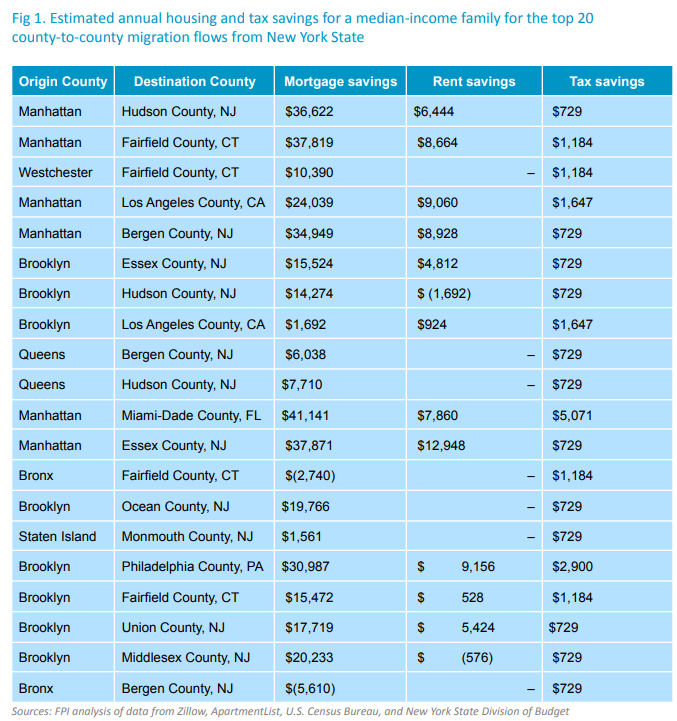

That said, there are things that policy can do to ensure that this process isn’t more painful than it needs to be. First, it’s essential that we have a strong and growing economy and labor market generally, as opposed to trying to pick winners in a particular industry or sector. Workers can and do move to other industries when shocks inevitably arise, but that process is much easier and more fruitful when labor market conditions are strong. Brand new research from the Cleveland Fed, in fact, shows that the hot U.S. labor market of 2021-22 was a big reason why American workers displaced during the pandemic had a better job-rebound experience than those displaced in previous recessions. Anecdotal evidence backs this up: Tech layoffs have swept across Silicon Valley and Big Tech, for example, but affected workers aren’t just sitting there waiting to be reemployed at the same firm or even in the same industry. They’re moving into other industries, such banking or health care, where the same general skills are needed (just in a different way) and where, because the economy is still pretty strong, demand for labor still exists. Predicting displaced workers’ optimal job or destination is a fool’s errand, but keeping the economy strong can help ensure that they find their way relatively quickly. In other words, contrary to what you might hear from your favorite populist, economic growth—fueled by pro-growth tax, trade, immigration, investment, regulatory, and other policies—remains vitally important.

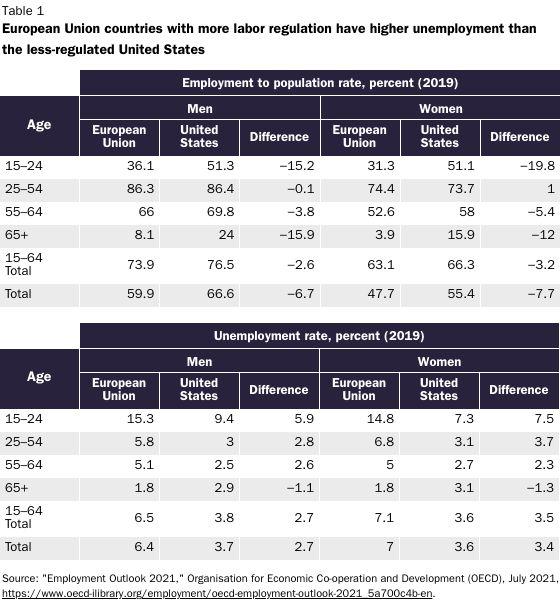

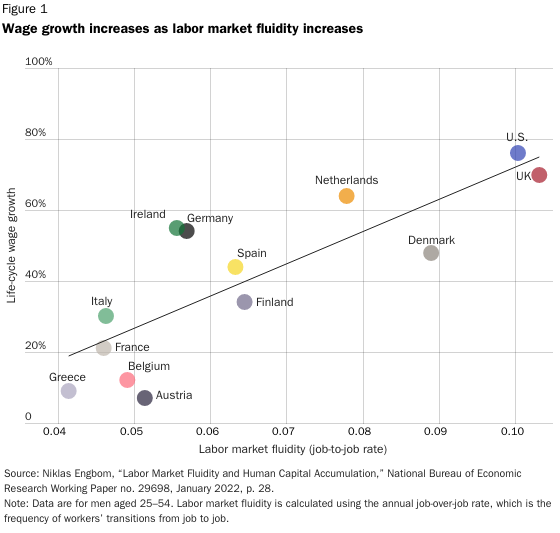

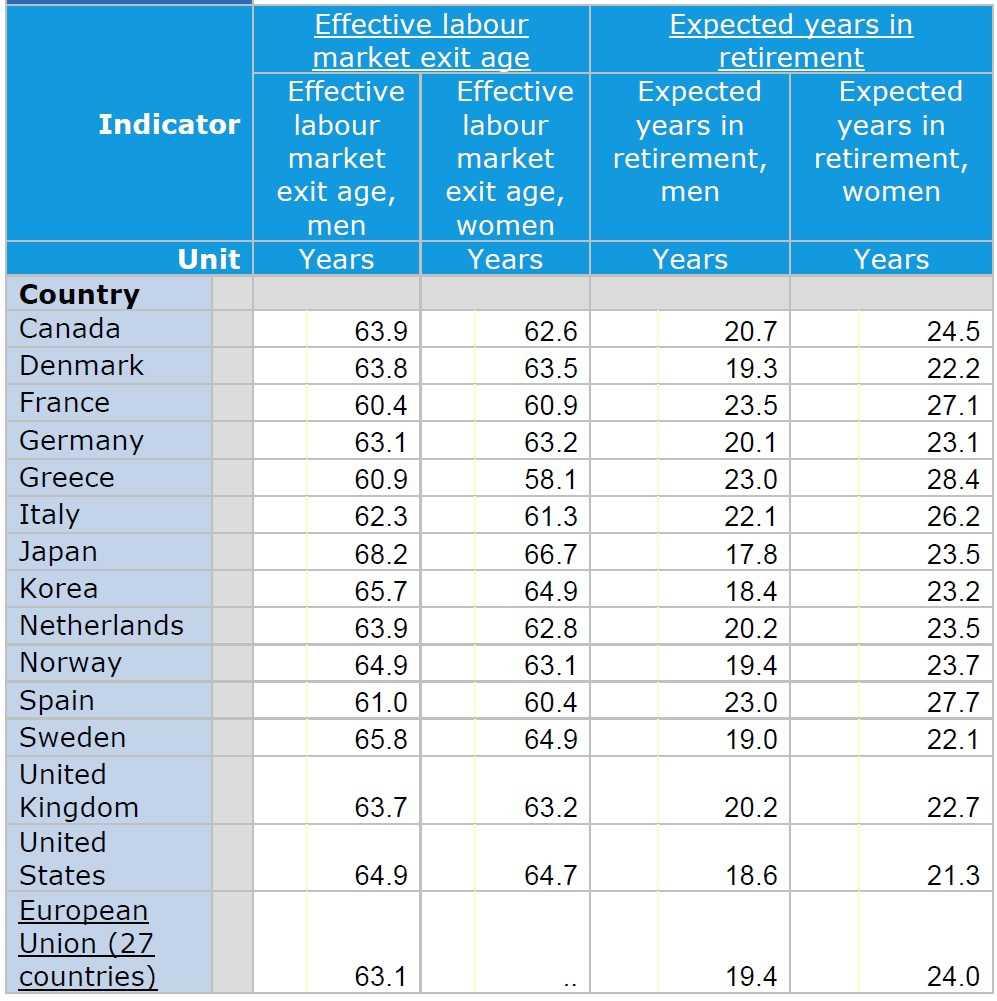

Second, the research above shows why U.S. policy at all levels should better emphasize worker autonomy and mobility—including via the many policy reforms proposed in my new Cato book (which you should review on Amazon if you’ve already been through it). As Bessen notes, for example, it was the United States’ relatively flexible labor market that allowed American workers displaced by computers to find new jobs in different occupations or industries. And, as noted in my book, research shows that more fluid labor markets tend to boost workers’ employment and lifetime earnings more than static, “European-style” ones with lots of labor regulation:

Policies that “protect” workers by tying them to certain jobs might sound like a good, “pro-worker” plan, but it can actually make them worse off in the long run. (Maybe someone can tell our political class.)

Similarly, the telephone operator paper shows why we need to reform or (even better) eliminate government policies that prevent or discourage workers from moving from job to job or place to place—before or after a shock hits. There, the authors note that newly unemployed phone operators were more likely to exit the workforce because “telephone operation—despite high turnover—was one of the few opportunities for women with the potential to be a career.” In other words, they may have had no other place to go. Fortunately, far fewer of those occupational barriers exist today for young women, but workers of all ages still face all sorts of laws and regulations—on employee benefits, licensing, housing, criminal justice, and so on—that make it harder for them to adjust when a shock occurs. Reforming those laws, as well as fixing our K-12 and higher education systems that remain wedded to a costly, archaic “one size fits some” system, should be a priority.

As I said in the book’s conclusion, we’ve repeatedly seen, including during the pandemic, that “American workers can, through their own initiatives, not merely survive our disruptive and messy modern world but eventually thrive therein.” History shows that we can survive the coming AI wave too—if bad policy doesn’t screw it all up.

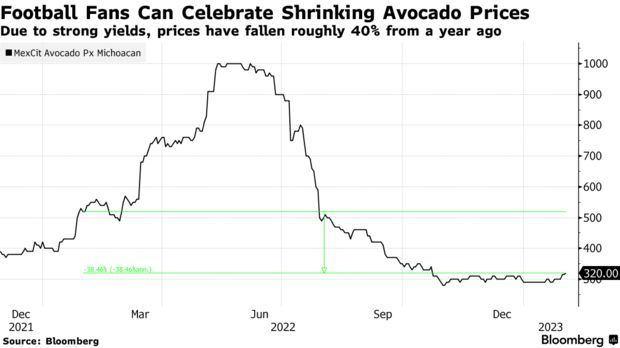

Chart of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.