Hang around the trade game long enough and you’ll frequently encounter examples of how bad law, policy, and politics hurt American businesses in infuriatingly dumb ways. What’s going on right now in the U.S. aluminum market ranks up there with some of the dumbest.

I found myself deep in this particular rabbit hole thanks to Magnitude 7 Metals, a Missouri-based primary aluminum smelter whose sudden closure last month pushed Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley to demand that President Joe Biden use the wartime Defense Production Act to magically save the factory. As Reason’s Eric Boehm patiently explained shortly thereafter, the senator’s demand—in somewhat typical fashion—never made much sense because the DPA isn’t some sort of magic “get out of economics free” card that can fix whatever market event politicians don’t like. For Hawley to pretend otherwise is pretty ridiculous stuff.

Dig a little deeper, however, and this is more than just another case of a politician screaming “DEFENSE PRODUCTION ACT” out a Capitol Hill window like Michael Scott declaring bankruptcy. Instead, it’s another teachable lesson regarding the sordid reality of modern U.S. tariff policy, and the high costs, unintended consequences, gratuitous system-gaming, and failed objectives that too often accompanies it.

Imports Aren’t U.S. Factories’ Primary (Get It?) Problem

Let’s start with the failed objectives. As frequent Capitolism readers are surely aware, reviving the U.S. primary aluminum (i.e., aluminum produced directly from mined ore) industry has been a central plank of recent U.S. tariff policy, most notably the “national security” tariffs that the Trump administration imposed in 2018 and that the Biden administration has since maintained. Among those lobbying for these tariffs was Magnitude 7, which said at the time that only tariffs could break America’s “dangerous dependence” on foreign aluminum and thereby revive U.S. primary aluminum production—including the idled Missouri plant that M7 had recently purchased on the cheap via bankruptcy proceedings.

Shortly after those tariffs were imposed, M7’s Swiss (yes, Swiss) owner reopened the Missouri smelter to much nationalist fanfare: Trump’s now-infamous trade adviser Peter Navarro cited it (and an Illinois steel factory that also recently ceased production) among the many tariff “success stories” that he claimed were spreading across the country. Trump himself—at a rally in Missouri with then-candidate Hawley—credited his “beautifully placed tariffs and very tough trade policies” (lol) for M7 opening. The union-friendly, tariff-loving Economic Policy Institute did much the same, albeit with less Trumpian flourishes. They certainly weren’t alone. As Reuters columnist Andy Home recently put it, the M7 factory was the “poster child for the Trump administration’s import tariffs.”

How right they all are.

Mere months after the plant reopened, warning signs emerged. By early 2020 (before the pandemic hit), Reuters reported that the company was “losing money at such a rapid clip that it could close within 60 days.” Its management again blamed imports for “undercutting the company’s position.” This time M7’s alleged problem was that Trump’s original tariffs didn’t cover stuff made mainly from aluminum (aka “downstream” products). Because overseas manufacturers of these goods weren’t saddled with the higher, tariff-driven aluminum costs their American competitors faced, they were able to offer lower prices in the United States, and their U.S. sales (imports) predictably surged.

So, we got more tariffs—lots more tariffs. First, Trump in 2020 extended his security tariffs to cover “derivative” products made mostly from aluminum and then reapplied them to Canadian primary aluminum (only to later relent on the tariffs while jawboning imports down to politically acceptable levels). Next came the “trade remedies” actions, which the Congressional Research Service summarized in a 2022 report:

Separately, there are numerous antidumping (AD) and countervailing duty (CVD) orders imposing punitive duties on aluminum and aluminum products. Most of these orders were put into place after the Trump Administration’s imposition of Section 232 duties. … As of September 2022, 34 AD or CVD orders concerning aluminum were in force, including many on semi-finished aluminum products imposed under the Biden Administration in 2021. In June 2021, the International Trade Administration in the Department of Commerce implemented the aluminum import monitoring and analysis system to track imports of aluminum products and provide an early warning of import surges.

The biggest of those AD/CVD cases was undoubtedly the one on aluminum sheet, which in 2021 imposed duties ranging from 5 to 242(!) percent on billions of dollars’ worth of annual imports from a whopping 18 different countries. (Numerous other tariffs had effectively shut major producers China and Russia out of the market, too.)

As we now know, none of this “cascading protectionism”—following tariffs on upstream inputs with tariffs on downstream products—saved M7. And that’s because, as is so often the case, the mill’s problems had little to do with allegedly “unfair” imports and almost everything to do with its own specific challenges.

As Reuters’ Home informs us, the plant suffered from two huge flaws. First, it “was built in 1971 and had the dubious distinction of producing the worst quality air in the United States in 2019.” As a result, the plant was under a state consent decree for sulfur dioxide pollution and had recently lost out on a state subsidy that would’ve financed a $7 million emissions reduction system to fix the problem. Second, the M7 factory was powered mostly by coal, which is not just dirtier than modern aluminum smelters but also more costly. Because energy is critical to primary aluminum production, the M7 facility just wasn’t competitive. Being dirtier and more expensive than the competition is not a recipe for success.

As Home notes, these types of problems were not unique to M7. Since 2021, in fact, the biggest players in the U.S. primary aluminum market, Alcoa and Century Aluminum, have quietly cut old, inefficient domestic operations by shutting down plants and reducing others’ capacity. That wasn’t because of China or Russia or whatever, but because these old facilities simply lacked easy access to the cheap, clean electricity that modern aluminum smelting needs. Fortunately, Home notes, there’s a place that enjoys such access, is officially part of the U.S. defense industrial base, and is a large and reliable supplier of primary aluminum to the U.S. market: Canada. In fact, because of abundant, green hydroelectric power up there, metals giant Rio Tinto is investing heavily in new Canadian smelters and continuously upgrading its older ones there.

Buying Canadian is thus an easy win—no “national security” tariffs, downstream protectionism, or magical invocations of the Defense Production Act (on behalf of a Swiss metals trading company!) needed.

But Wait, There’s More

We find even more absurdity down the supply chain via yet another AD/CVD case against an imported aluminum product, lithographic printing plates (used to make newspapers, magazines, books, and other printed materials) from China and Japan. Here, the lone U.S. producer Kodak (yes, that Kodak) has asked for tariffs of 23 to 108 percent on imported printing plates. The company alleges that its main global rival, Japan-based Fujifilm, is a) selling them in the United States at unfairly low or subsidized prices and b) thereby causing significant financial harm (aka “material injury”) to the U.S. printing plate industry, which today consists of only Kodak. (Refresher: U.S. AD/CVD cases require findings of both dumping/subsidization, determined by the Commerce Department, and injury, determined by the International Trade Commission (ITC). Duties are imposed if both agencies make such findings in a process that takes about a year to complete.)

Those allegations, however, fall apart under scrutiny. First, according to the public documents now on file with the ITC, the main evidence of “material injury” in this case appears to rest not with Kodak’s own operations or financial performance but with a now-closed plant in Greenwood, South Carolina, that was owned by … wait for it … Fujifilm. (In the interest of full disclosure, I did some legal work for Fujifilm before I left the law and went to Cato in mid-2020, but I have no inside knowledge of this stuff—only general familiarity with the current situation based on the case docs.) The Japanese company decided in 2021 to wind down the South Carolina facility and use its factories abroad to service the shrinking U.S. market for printed materials. That consolidation process, which concluded in mid-2022, meant gradual increases in Fujifilm imports into the U.S. to offset gradual reductions in the South Carolina factory’s output, employment, and everything else that accompanies a plant shutdown. Those events might appear grim when assessing the U.S. printing plate market from 50,000 feet, but they have absolutely nothing to do with the market today or the only remaining domestic producer, Kodak.

Yet, thanks to the bizarre and often-ridiculous world of U.S. trade law, the ITC preliminarily ruled that Fujifilm’s South Carolina facility counted as part of the domestic printing plate industry (and would thus be included in its analysis of whether imports—mainly from Fujifilm!—were harming that industry). In short, the ITC just found that future U.S. tariffs on Fujifilm’s imports might be warranted because Fujifilm—Kodak’s main competitor—was injuring itself more than two years ago. You can’t make this stuff up.

Second, Kodak’s own actions strongly indicate that, to the extent injury actually has been occurring in the U.S. printing plate market, it’s because of U.S. aluminum tariffs, not printing plate imports. Aluminum sheet constitutes printing plates’ single largest raw material cost, and there’s no longer a domestic producer of the highly technical “lithographic” sheet product that U.S. printing plate producers need. (Alcoa exited this niche market in 2017.) Imports, meanwhile, have recently faced three different types of tariffs: global “national security” tariffs, China-specific tariffs, and all those AD/CVDs. And, unsurprisingly, aluminum sheet prices increased between 2020 and 2022, as did the raw materials’ share of domestic producers’ total costs. (See the ITC prelim report at pages 26-27.)

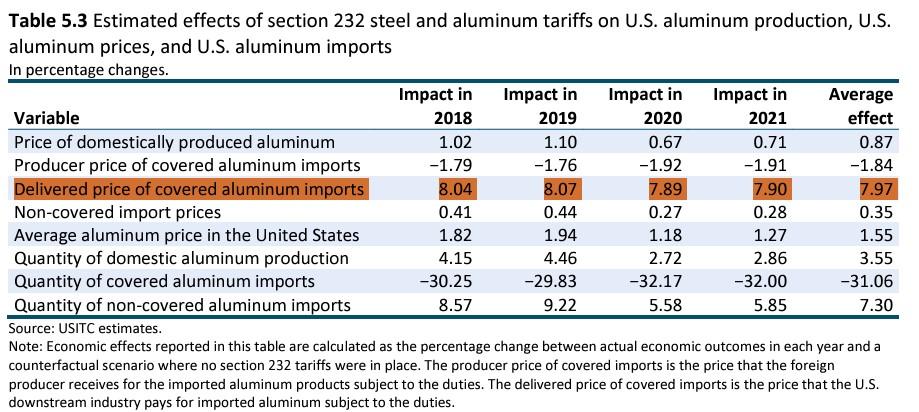

Proving the U.S. tariffs actually caused the price pressures that the ITC observed is a complicated affair, particularly during the pandemic, but tariffs surely deserve some of the blame. For starters, a separate ITC report found that the 10 percent national security tariffs by themselves increased aluminum import prices by about 8 percent:

Furthermore, both Fujiflim and Kodak agree that U.S. trade policy is causing problems for their U.S. operations. The former explained to the ITC that “continuing production at Greenwood was hamstrung by unreliability in the supply of competitively priced aluminum sheet” because of both Alcoa’s 2017 exit and various U.S. tariff actions. After the 2021 AD/CVD case, in fact, there was only one raw material supplier in the entire world, in the United Kingdom, that wasn’t subject to U.S. trade remedy duties. Even that supplier faced the “national security” tariffs (yes, even though the U.K. is one of our closest allies).

Kodak’s actions speak even louder. The company has spent the last couple years avoiding any and all tariffs that might affect its bottom line—including, believe it or not, the ones on printing plates that it’s now requesting:

- First, starting in 2019 Kodak successfully petitioned for an exclusion from the national security tariffs because the needed raw material wasn’t available in the United States—a process it has to repeat every year. In the 2023 petition, Kodak explained how these tariffs would affect its operations: It needed an exclusion because “the additional tariffs proposed on imported aluminum will have a grave effect on Kodak’s printing business, its printing plate manufacturing within the United States, and ultimately, on its mostly small to medium-sized customers in the print industry.”

- Kodak has since worked to avoid the AD/CVDs on aluminum sheet via a “changed circumstances review” that has asked the Commerce Department to exclude lithographic sheet from Germany, which Kodak buys (plus 16 percent duties). Just last week the Commerce Department preliminarily approved that request and is mulling Kodak’s request to make that decision retroactive to 2020 (meaning big duty refunds for Kodak). That result, however, is pending.

- Finally, Kodak has excepted its own foreign production from the current AD/CVD case on printing plates. According to the ITC case documents, Kodak has a manufacturing facility in Germany that makes printing plates and ships them to the United States. Naturally, Kodak’s new AD/CVD case excludes Europe (even though another producer, Eco3, also ships to the United States from there too) and instead focuses on only where Fujifilm, Kodak’s biggest rival, has facilities.

So, to recap: Kodak today is the only U.S. printing plate producer because its main U.S. competitor shut down its South Carolina factory years ago. Kodak wants to use that closure to justify new tariffs on imports from that same competitor, while carving out both its own imports from those tariffs and from tariffs on its main raw material—tariffs that probably helped put the South Carolina facility out of business in the first place.

Like I said, you can’t make it up.

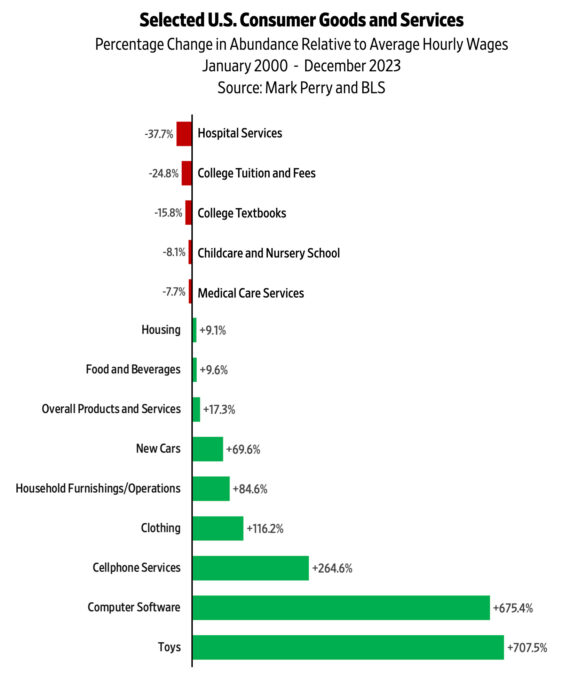

There are, of course, other reasons for the South Carolina factory closure. Most obviously, digital media and dirt-cheap screens (thanks, globalization!) have collapsed U.S. and global demand for printed materials and the things that make them, including lithographic printing plates. Because demand remains strongest in Asia, it makes sense for Fujifilm to maintain factories closest to those consumers (and its headquarters) and simply export to dwindling markets abroad. By being headquartered in the United States and closer to U.S. customers, Kodak benefits from such consolidation, which it’s undertaken in recent years, too.

However, shifting demand isn’t unique to printing, and the companies’ own words and (especially) deeds show that U.S. tariff policy made Fujifilm’s closure decision easier. Just think of it this way: If you’re a giant multinational corporation that needs to consolidate global operations and has headquarters and facilities in Asia, and only your U.S. facility faces significantly higher raw materials costs and constant market uncertainty—not to mention pricey lawyer bills for things like tariff exclusions and AD/CVD cases—deciding which facility to close isn’t exactly a tough call. For the company’s main competitor to then use that closure to justify even more tariffs is just icing on the cake.

Summing It All Up

Tariffs on upstream aluminum products spawned tariffs on downstream aluminum products which have now spawned requests for even more tariffs on aluminum products from a politically connected company that, naturally, wants tariff exemptions for itself. At least one downstream factory in the United States is closed, while several upstream plants are too. Judging from the thousands of desperate requests from U.S. manufacturers for tariff relief, surely others are in trouble too.

But instead of blaming the tariffs for this giant mess (and, heaven forbid, simply letting American companies buy aluminum from companies in Canada, the U.K., Japan, and other nations), the tariff-loving senior senator from Missouri wants the president to save his state’s factory by magical government fiat. It’s almost all too crazy to believe … unless, of course, you’ve actually been paying attention.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.