Dear Capitolisters,

Early in 2022, I wrote how President Biden’s first year guiding U.S. trade policy was a mostly expected mix of good (better than Trump), bad (Trump 2.0), and ugly (actually worse). Recent events require me to update to those conclusions, and—spoiler alert—things have deteriorated significantly. In fact, it’s not hyperbole to say that Biden’s latest trade moves might pull the plug on the multilateral trading system as we know it.

(Insert ominous music here.)

A Brief History of the WTO

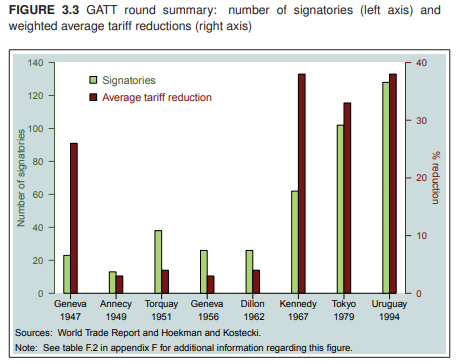

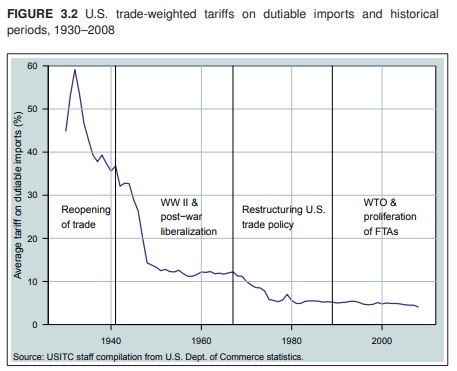

Before we get to that, some quick background. In response to multiple world wars caused in part by trade frictions, officials from several governments, led by the United States, created the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947. That agreement did two main things: 1) created a baseline set of multilateral (global) rules for member countries to voluntarily follow; and 2) established an impartial process for resolving government-to-government disputes related to those rules. In some ways, the GATT was pretty successful: Participating governments agreed to channel most trade restrictions into tariffs (the most transparent/predictable, and thus least distortive, barrier), to cap those tariffs at certain levels (incrementally lowered via subsequent negotiating rounds), and to not discriminate in favor of certain other members (aka “most-favored nation” treatment or “MFN”) or their domestic industries (aka “national treatment” or “NT”). Over time, the combination of declining tariff levels, transparency/predictability, and non-discrimination—along with non-trade things like containerized shipping and information technology—caused world trade to increase significantly. Cross-border armed conflict also declined, which many experts attribute (at least in part) to trade integration. And, seeing these benefits, many non-member nations sought to join the party.

The GATT, however, was also flawed in important ways. Most notably, its rules didn’t cover important and growing trade areas (e.g., services and investment) and had big loopholes for certain non-tariff barriers. And its dispute settlement system was a mess. A single member could block a panel decision from entering into force, there was no coherent appeals process or standing appellate body, leading to incomplete and inconsistent rulings, and member nations frequently ignored implemented rulings.

Governments spent years negotiating to fix many of the GATT’s major flaws while maintaining the agreement’s core principles of non-discrimination and national sovereignty. The GATT’s successor, the World Trade Organization, came online in 1995 and—while not perfect—was a clear improvement over the old system: New agreements extended nondiscrimination policies to other areas of trade, more nations committed to follow these rules, and the dispute settlement system was overhauled. Now, panel decisions could be appealed to a new and permanent Appellate Body, and final rulings could no longer be blocked or ignored. Being sovereign nations, WTO members that lost a case could choose not to implement a given panel/AB decision (for political or other reasons). But noncompliance—following a lengthy appeals and compliance process—meant that a winning member could retaliate in kind (primarily by withdrawing trade benefits, such as lower tariffs, that it had previously granted the losing party via the WTO agreements). Contrary to conventional wisdom, the WTO wasn’t a “trade cop” or anything like that; everything—new rules, new disputes, new enforcement, etc.—was driven by the members themselves, with the WTO being simply an independent arbiter of the rules to which everyone agreed.

For all its warts, the WTO system proved to be successful both in helping to liberalize trade via a baseline set of core rules and principles and in providing a mechanism for members to settle disagreements without resorting to self-defeating, ever-increasing protectionism or, even worse, shooting at each other. As I co-wrote a couple years ago:

Through numerous multilateral negotiating rounds and the resolution of hundreds of disputes, the WTO and its predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), have been remarkably successful. When the United States and its allies began negotiating the GATT shortly after World War II, the average tariff of participating countries was 22 percent. In 2018, the world’s applied tariff was just 9 percent. Though declining slightly this year due to a number of factors, including trade tensions between Washington and Beijing, trade volumes have grown by over 4 percent annually (on average) since the WTO was first established in 1995. Likewise, the United States has effectively used the WTO’s dispute settlement system to hold countries accountable for violating their binding commitments. The president’s own Council of Economic Advisers acknowledged that the United States wins more than 85 percent of the cases it brings to the organization.

Research also shows that members—yes, even China after it acceded to the WTO in 2001—usually agreed (again, voluntarily) to comply with WTO rulings they lost, and that this compliance, while surely not universal or perfect, produced far better economic and geopolitical outcomes than the previous GATT approach of nations taking matters into their own hands via tariffs or other protectionist measures. In short, the now 164 participating member governments so valued the WTO system and its trade and geopolitical benefits that they were willing to occasionally take their dispute lumps—whether through eliminating their protectionist measures or just agreeing to accept the WTO-authorized retaliation when the political cost of compliance proved too high.

Then Came Trump

As I’ve written repeatedly, the WTO has suffered from various problems for years—disputes took too long to resolve, certain rules needed updating, consensus among 160-plus members proved increasingly difficult, and so on. But the baseline rules and dispute settlement system continued to function reasonably well … until Donald Trump came along. In particular, the United States:

- Blocked the seating of new WTO Appellate Body members and pledged to do so until the organization undertook major “reforms” (which were never really pursued in earnest, especially given the need for everyone to agree to them). As a result, the WTO’s dispute settlement system ceased to function properly: Panels could still issue a decision, but a member could block its implementation by appealing it “into the void” (because there was no AB). So why even bother?

- Implemented global steel and aluminum tariffs on obviously bogus “national security” grounds. (Briefly: Even if one were to ignore the U.S. steel industry’s financial health, stable output, and high domestic market share, Trump’s own Defense Department said it needed only 3 percent of U.S. production and didn’t support tariffs on imports from allies.) As Trump himself occasionally admitted, these tariffs had little to do with actual national security and were thus a flagrant abuse of the WTO’s ambiguous and highly deferential exception for measures taken to protect members’ “essential security interests.” For more than six decades, GATT/WTO members had mostly avoided invoking this loophole for illegitimate (protectionist) purposes out of fear that doing so would spark copycat “national security” protectionism, put dispute panels in an unwinnable position of having to debate members’ invocation of “national security,” and thus imperil the WTO system altogether. It was the “third rail” of international trade law, and President Trump grabbed it with both hands and then held a big photo-op with the U.S. steelworkers union to celebrate.

Combined, these two policies inflicted severe damage on the WTO system. Under the “Trump Doctrine,” the invocation of “national security” was a get-out-of-trade-free card, regardless of how absurd and blatantly protectionist the measures at issue were, and the AB-less WTO couldn’t effectively adjudicate any such moves. It’s a protectionist loophole you could drive an (American-made) tank through.

Will Biden Finish the Job?

Most WTO members, to their credit, did not hop on the Trump Doctrine bandwagon. “National security” measures have proliferated a bit, but mainly against just one nation (China) and usually in relation to goods that—unlike most grades of still-tariffed steel (e.g., rebar)—have at least some plausible national security nexus. The WTO has thus continued to limp along, patiently waiting for some sort of negotiating breakthrough.

The Biden administration’s latest moves, however, may cause nations to reconsider this approach.

First, the Biden administration has surprisingly doubled down on the United States’ neutering of the WTO dispute settlement system. Thus, the Appellate Body remains in stasis; WTO members are increasingly appealing unfavorable panel decisions “into the void”; and—unsurprisingly—they’re also bringing fewer cases as compared to the historical averages. As trade lawyer Simon Lester laid out in March, the Biden administration’s position here is, just like Trump’s, indefensible—the U.S. is not only blocking AB appointments, but also has proposed zero actual, concrete reforms that would, if enacted, clear the logjam.

Second, the Biden administration has doubled down on not only Trump’s metals tariffs (which mostly remain in force, including against friendly nations), but also his harmful, nonsensical “national security” defense. In particular, after several WTO members predictably challenged the tariffs in dispute settlement, Biden’s U.S. trade representative continued her predecessor’s vigorous insistence that the WTO’s “national security exception” (in GATT Article XXI for trade in goods) prevented a panel from even considering the issue. As my Cato colleague (and former congressman and WTO Appellate Body chair) James Bacchus detailed in a new paper last month, the U.S. position here is, like its position on the AB, indefensible: Not only does a basic review of the multi-paragraph text (and longstanding principles of treaty interpretation) show that a WTO panel could properly examine member’s invocation of the national security defense, but it was the United States itself that pushed for this wording and vigorously promoted the obvious interpretation in the early GATT days. Per Bacchus: “It is clear from the negotiating history that, at the time, the United States did not view the Article XXI exception as a mechanism to excuse all restrictions on trade that might be labeled by the country imposing them as national security measures. Quite the opposite.”

In short, if GATT Article XXI and the other WTO national security exceptions were truly as broad as the U.S. now (conveniently) claims, it’d permit any and all protectionism and block members’ recourse to dispute settlement to adjudicate it—thus defeating the entire purpose of having not just detailed security exceptions in the agreement, but any agreement at all. Perhaps tellingly, Bacchus notes that the only WTO members who’ve pulled similar stuff are Russia and Saudi Arabia. Huh.

Anyway, last Friday a WTO panel finally admitted the obvious: The U.S. steel and aluminum tariffs clearly violate various rules disciplining tariff levels and discrimination, and the U.S. invocation of “national security” was bogus because, while nations can freely determine their own “security interests,” they still need to abide by Article XXI’s express conditions about when and where security-related protectionism wouldn’t run afoul of the rules (wonky details here). Instead of accepting the decision, the Biden administration threw a fit and immediately responded that the United States:

- “strongly rejects the flawed interpretation and conclusions” in the panel reports;

- “has held the clear and unequivocal position, for over 70 years, that issues of national security cannot be reviewed in WTO dispute settlement and the WTO has no authority to second-guess the ability of a WTO Member to respond to a wide-range of threats to its security” [ed. note: this is false];

- “will not cede decision-making over its essential security to WTO panels” [ed. note: the panel didn’t say this]; and

- “do[es] not intend to remove the Section 232 duties as a result of these disputes.”

You couldn’t capture the Trump Doctrine any better if you tried.

In a new and scathing blog post, Bacchus corrects the USTR’s legal and historical mistakes and suggests that the United States will appeal the decision “into the void” to ensure that the complaining members—including notorious trade villains and U.S. adversaries Switzerland and Norway (ha)—can’t avail themselves of the WTO’s traditional retaliatory response, further undermining the system. He also (and rightly) finds politics—not law—motivating the dangerous Biden administration moves:

Acceptance by WTO jurists of the contemporary and bipartisan U.S. view that the WTO has no jurisdiction on such matters, would open up a black hole of national security in which professed national security measures of all kinds could swallow up the entirety of all WTO obligations—something the United States itself warned against when the national security exception was written at the creation of the multilateral trading system in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War. This would be the end of the multilateral trading system. The Biden administration, however, seems not to be interested in this possible disastrous outcome of its intransigent position.

Instead, the president and his trade team are, in this as in most other aspects of their trade policymaking, looking only to the near political term in the runup to the next presidential election in 2024. Hypocritically, the Biden administration has pretended for nearly two years that, unlike the previous Trump administration, it wishes to restore the full functioning of the WTO dispute settlement system. USTR Katherine Tai has whispered sweet trade nothings into the ears of WTO members and WTO supporters in Geneva and elsewhere, and, as people sometimes tend to do, they have heard what they wanted to hear.

For those wondering, Bacchus is a Democrat.

So Now What?

Contrary to what you might hear on Twitter or the New York Times’ opinion page, the issues before us today—on China, Russia, climate change, and so on—are neither unique to our age nor unaddressed by global trade rules. As I taught college students years before Trump became president, nations and the WTO’s adjudicators have long grappled with how to balance open and non-discriminatory trade with national sovereignty and security, domestic regulation, cultural differences, foreign policy, and—yes—even domestic politics. The GATT and now WTO agreements deal with these very things in nuanced ways, and members occasionally renegotiate their terms or even refuse to comply with discrete rulings. Throughout it all, however, they’ve recognized the overall economic and geopolitical value of the system, publicly vowed to maintain it, and accepted the costs of their occasional disagreement (see, e.g., past U.S. noncompliance on cotton subsidies or internet gambling).

The United States no longer does.

To be clear, this does not mean I’m revising my optimistic conclusions about the overhyped “death of globalization”—there remain plenty of reasons to believe that world trade will continue apace (albeit differently). But I do increasingly worry that the future of globalization, for the next several years at least, could be lacking two of its longstanding pillars—the WTO and the United States. Indeed, it’s not as if the Biden administration’s disregard for trade rules is limited to steel tariffs. Just last week, for example, we learned that an independent panel composed under a different trade agreement (the NAFTA-replacing U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement) had ruled against the Biden administration’s protectionist interpretation of already-protectionist “rules of origin” governing North American automotive trade. And as I and many others have noted (and much to the chagrin of Europe, Japan, South Korea, and other U.S. allies), the Inflation Reduction Act contains all sorts of discriminatory industrial subsidies that clearly violate WTO rules. Biden’s U.S. trade representative lauds this as a feature, not an unwelcome-but-necessary side effect, of Biden economic policy (other Biden officials do too), and it’s something U.S. protectionists have cheered as a “knife” to the multilateral trading system. Last week, the administration twisted that knife.

Whether other countries follow the U.S. lead remains to be seen. But the odds are higher today than they were six months or even a week ago.

There’s also the risk that Biden’s isolationist approach will extend beyond discrete policies like steel tariffs or EV subsidies to bigger and more important international initiatives that the United States is trying to spearhead, including on China and Russia. As Tufts University’s Dan Drezner noted a couple days ago:

The Biden administration simultaneously wants to claim that “America is back” from the bad old days of the Trump administration while implementing an awful lot of trade restrictions that target U.S. allies. The inherent tension between these two aims is not going to go away — which means that, from time to time, I will have to remind readers about the logical hole at the center of Biden’s grand strategy. Or as Brad DeLong recently explained to the Financial Times, “The U.S. is now an anti-globalization outlier.'”

Being that outlier means not just losing out on trade’s proven economic benefits, but also being a non-participant or backbencher in whatever spaghetti bowl of new international agreements that supplements or supplants the WTO. (Much to China’s pleasure.) As foreign policy expert W.R. Mead noted back in May, moreover, “the promotion of free trade has been the most powerful tool for American diplomacy since World War II.” And since then, the WTO has been at the center of that approach.

Maybe abandoning it makes for good politics in the Rust Belt, but at what cost?

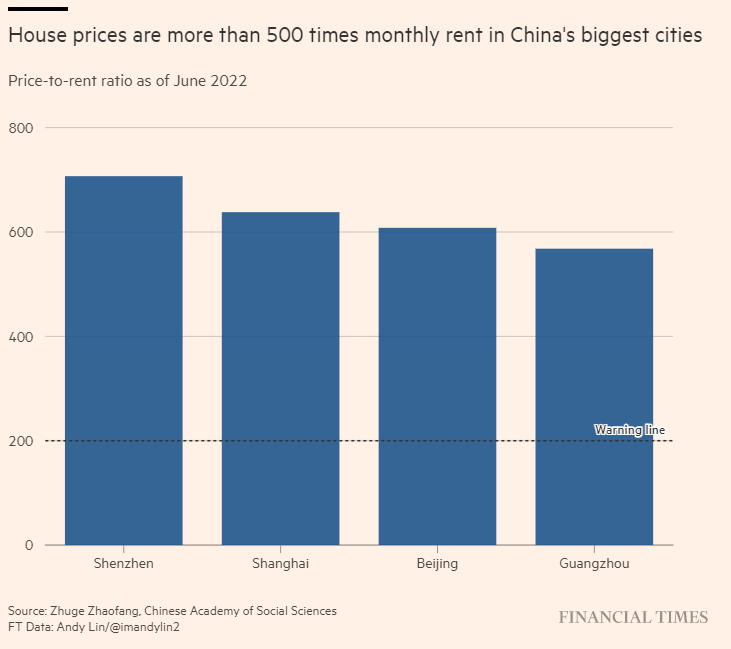

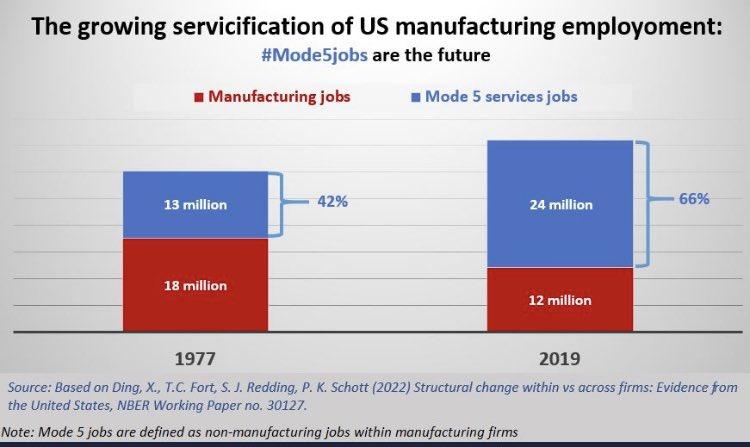

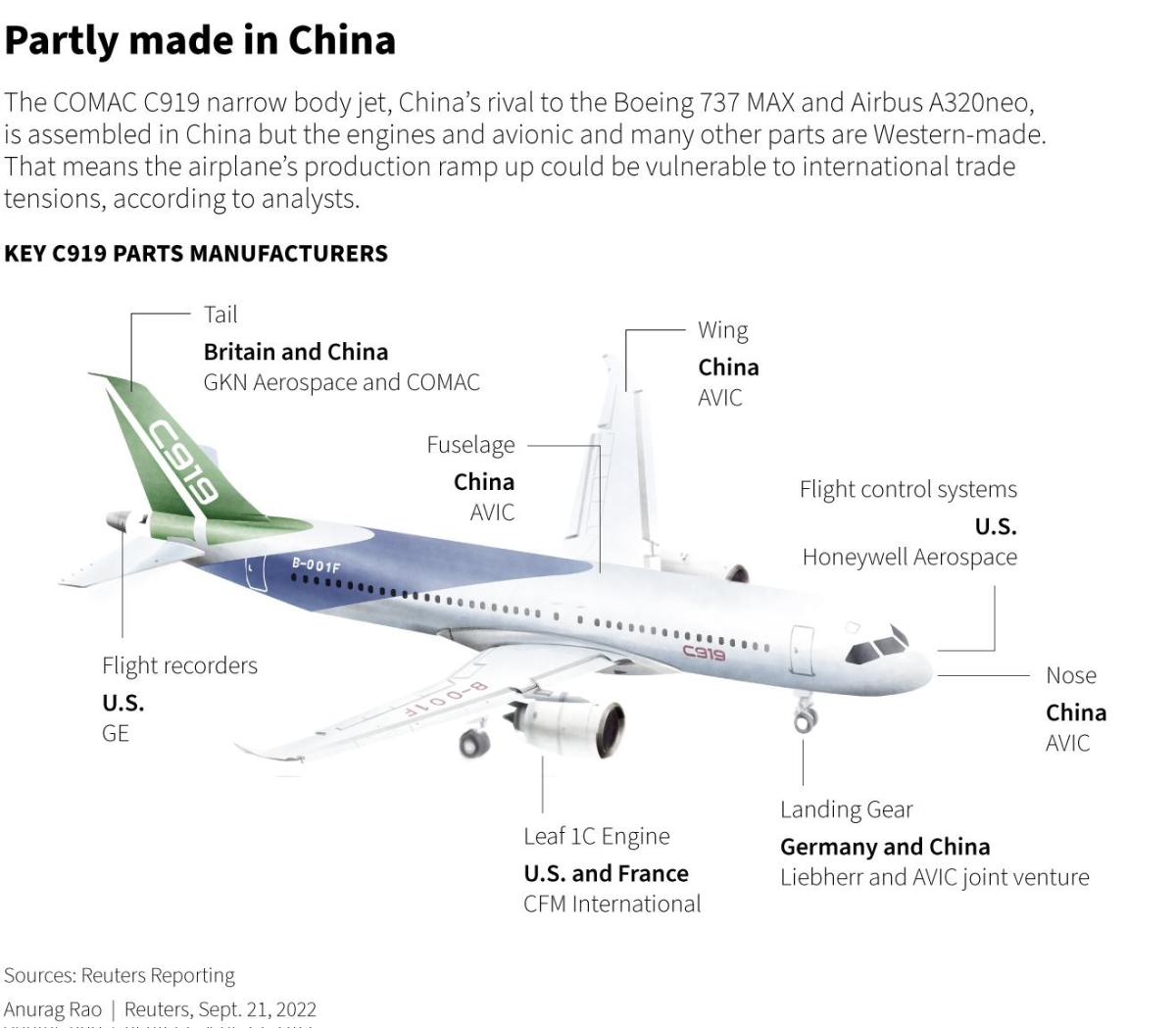

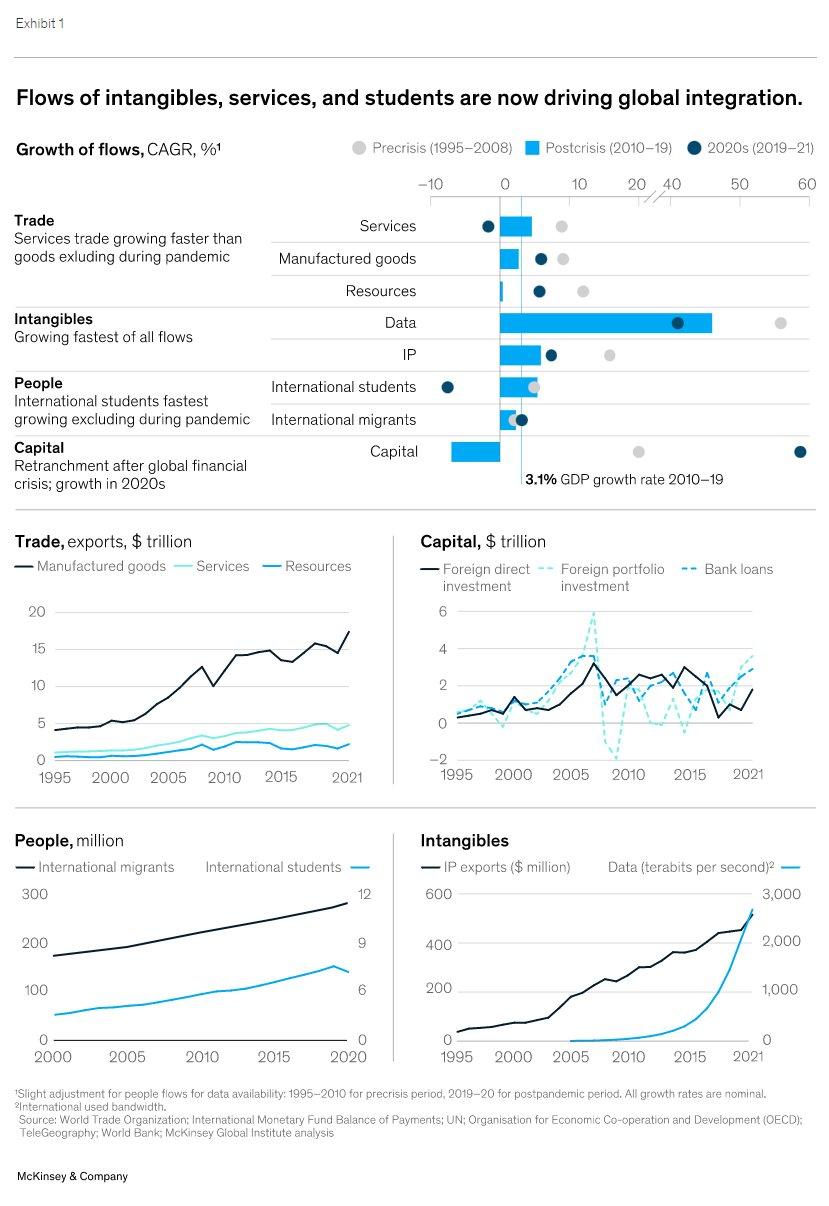

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.