When it became clear in late 2023 that Javier Milei would become the next president of Argentina, the response from many economists and analysts was borderline apoplectic. They warned that the profane self-described libertarian—who looks more like a still-touring ’80s rockabilly singer than the classically trained economist he actually is—would inflict on Argentina’s already-beleaguered economy “deep recession,” “devastation,” “economic collapse,” and all sorts of other economic horribles. I, on the other hand, was cautiously optimistic—liking Milei’s initial moves but still worried that Argentina’s problems would prove insurmountable for a dog-cloning, chainsaw-wielding political neophyte facing serious opposition at home and serious skepticism abroad.

Then, a funny thing happened as Milei worked to enact his slash-and-burn agenda: Things in Argentina got better, and the doomsayers went quiet. A few brave souls, to their credit, have since issued mea culpas, but most of them haven’t. That’s probably because doing so would acknowledge the success of not only Milei, but also the libertarian ideas they so disdain.

What Milei Did (and Why)

To understand just how daunting a task Milei has faced, it’s important to first reiterate just how bad things had gotten in Argentina before he took office. Thanks to decades of Peronist mismanagement and corruption, an Argentinian economy that once paralleled those of the world’s wealthiest countries had become a global laughingstock with skyrocketing inflation, routine fiscal crises, and crippling poverty. As my Cato Institute colleague Ian Vásquez summarized in January, “Milei inherited a country suffering from more than 200% inflation in 2023, 40% poverty, a fiscal and quasi-fiscal deficit of 15% of GDP, a huge and growing public debt, a bankrupt central bank, and a shrinking economy”—brutal conditions that undoubtedly helped propel Milei into office.

Inaugurated in December 2023, Milei immediately set about to reverse these and other trends by shrinking the bloated Argentine bureaucracy, slashing government spending, and in turn getting inflation under control. Within the first month, he’d cut the number of government ministries in half—from 18 to nine—and cut spending by 30 percent, thus producing Argentina’s first monthly budget surplus in more than a decade.

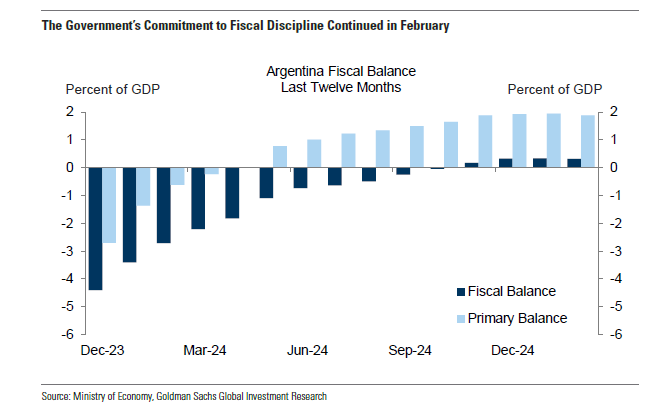

He then moved to enact an aggressive “omnibus” reform bill, which included vast and structural spending and regulatory reforms but was substantially scaled back because of a still-adversarial legislature. Nevertheless, these and other fiscal reforms achieved what economists Sebastian Galiani and Santiago Afonso called in a November paper “the most aggressive one-year fiscal consolidation ever recorded,” with greater spending cuts in just six months than Argentina’s last right-leaning president, Mauricio Macri, did in four years. Just as importantly, Milei “demonstrated an unprecedented commitment to maintaining” the cuts, as evidenced by “the vetoes President Milei issued against laws approved by Congress that would increase public spending”—moves that “have served to enhance his credibility regarding the future sustainability” of the nation’s new “fiscal equilibrium.”

As shown in a new chart from Goldman Sachs, such credibility is well-deserved:

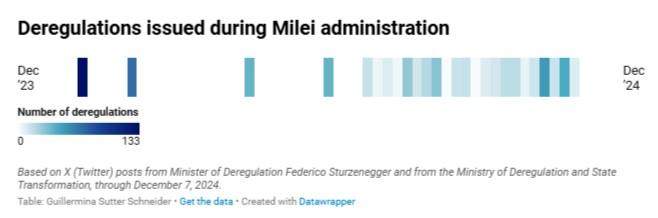

As Vásquez documents, however, it may be Milei’s deregulatory work that’s even more impressive—and important for Argentina’s future. In a new piece this week, he explains how the Peronists’ power is entrenched in the bloated Argentine bureaucracy, and that Argentina’s regulatory state is simply massive. Thanks to 300,000 different laws, decrees, and resolutions, the Human Freedom Index finds Argentina to be “one of the most regulated countries in the world,” with a regulatory burden ranking 146th out of just 165 countries.

This is where Milei’s chainsaw has been directed. Along with the ministry consolidation (now down to eight), Milei in his first year in office “fired 37,000 public employees and abolished about 100 secretariats and subsecretariats in addition to more than 200 lower-level bureaucratic departments.” He’s also rapidly deregulated across the economy, starting with the broad Decree 70/2023—the so-called Megadecreto (Megadecree!)—and then continuing unabated for the next year. In a December blog post, in fact, Vásquez and colleague Guillermina Sutter Schneider calculated that in Milei’s first year in office, his administration had implemented 672 regulatory reforms (331 eliminated and 341 modified), or around two per day for an entire year.

Perhaps most famous of these moves was in housing, with the Megadecreto’s quick repeal of Argentina’s onerous rent controls and mandatory minimum tenancy requirements to boost an Argentine housing market suffering from real rents that had actually grown faster than the nation’s sky-high inflation. But Argentina’s deregulation efforts hit many other sectors, including pharmaceuticals, technology, transportation, tourism, energy, and agriculture. Milei’s administration also improved regulatory procedures—inspections, testing, permits, licenses, warehousing, personnel, etc.—to reduce burdens on new and existing businesses and to improve enforcement.

Under Milei, Argentina also has liberalized trade. The government has reduced or eliminated various trade regulations, such as import licenses for appliances and clothing, “Buy Argentina” mandates and nationalist shelf-stocking requirements, commercial airline restrictions, and strict limits on imports intended for personal use. The administration also recently announced a “revolutionary deregulation” allowing unencumbered import and export of food that’s already been approved by a competent regulator abroad. It has unilaterally cut tariffs on consumer goods, nixed a blanket tax on all imports (and one on overseas debit/credit card purchases), and reduced export taxes on agriculture. And, while much of the world is embracing (or terrified of) populism, Milei is out there making big speeches on the benefits (and moral imperative) of free trade and the evils of protectionism.

In these and other moves, Vásquez explains, Milei’s team of legal experts and economists have pursued a clear mission: “to increase freedom rather than make the government more efficient.” And they’re still going: “According to [Argentina’s minister of deregulation and state transformation Federico Sturzenegger], the government has cut or modified 20 percent of the country’s laws; his goal is to reach 70 percent.”

Giddyup.

That said, my Cato colleagues and other free marketers aren’t thrilled with everything Millei has done, and many of his reforms—whether due to a lack of legislative support or simply caution—are modest and incomplete. As Galiani and Afonso show, for example, Milei’s spending moves have haven’t come via permanent, structural reforms, meaning that “sustainability is highly dependent on continued public support for the administration.” They add that consumer energy subsidies remain high and “excessively cautious,” while Vasquez notes that “Argentina still has a closed economy with barriers to trade and tight capital and exchange controls” that Milei says he’ll liberalize only once the economy further stabilizes. My Cato colleagues lament, moreover, that Milei has neither embraced “dollarization” (adopting the U.S. dollar as the national currency) nor shut down Argentina’s central bank, both of which are seen as ways to prevent a return to the government’s disastrous history of excessively printing money to finance profligate public spending. (Milei says he is still committed to abolishing the central bank eventually.) Given just how hyperregulated Argentina’s economy was before Milei took over, there’s also plenty more to be done on the regulatory front—something his team openly acknowledges.

With legislative elections in October of this year and polls currently tight, more caution is expected in the coming months—even if the still-closed nation could use much more economic radicalism.

The Results So Far

Nevertheless, it’s increasingly clear that Milei’s reforms have thus far achieved good results that few non-libertarians expected. Most notably, monthly inflation has fallen from a crippling 25 percent in late 2023 to a still-bad-but-undeniably-better 2.4 percent as of February, and experts expect the country’s annual inflation rate to “plunge” to 23 percent in 2025. Along with the budget surpluses, moreover, Vásquez documented in December that the nation’s fiscal position has been much improved:

Central bank debt was transferred to the Treasury, where it is being managed more transparently and on better terms. Thus, Argentina has not only avoided default but has also generated growing confidence in its economy. Its country risk declined from over 2,100 points in January to around 735 points now. The economy has begun to recover, especially in certain sectors such as agriculture and energy.

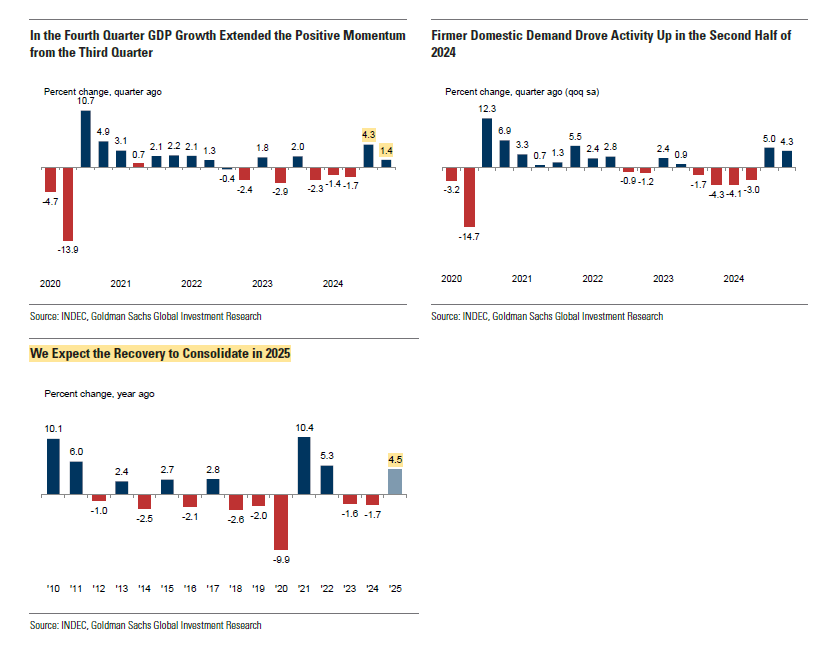

The overall economic picture is also undeniably brighter. Fueled by strong domestic demand, Argentina escaped recession in mid-2024, has now had two quarters of solidly positive, expectations-beating GDP growth, and is widely expected to do even better in 2025:

The unemployment rate is trending down; labor force participation is trending up, and real wages have strongly rebounded:

Bloomberg adds that, “With wages picking up, private estimates monitored closely by the government indicate poverty declined below 37% by the end of 2024 after surpassing 54% at the start of the year.” Other surveys have shown even bigger declines.

Meanwhile, the trade and regulatory efforts are also bearing fruit. Per Goldman Sachs, fourth quarter exports increased by more than 27 percent versus 2023, while imports increased by almost 10 percent over the same period. As Cato’s Ryan Bourne documented over at Reason, mere months after Milei ended rent controls, rental housing supply in Buenos Aires was 212 percent higher than in December 2023; and “the real price of renting fell almost 27 percent in the first seven months after deregulation occurred.” Here’s the killer chart from the Wall Street Journal:

Vásquez gives other examples of where deregulation is working, beyond housing.

- A new “open-skies” policy and other moves have “led to an increase in the number of airline services and routes operating within (and to and from) the country.”

- Deregulating satellite internet services “has given connectivity to large swaths of Argentina that had no such connection previously,” with one remote town seeing “a 90 percent drop in the price of connectivity.”

- Allowing non-pharmacies to sell over-the-counter medicines “has resulted in online sales and price drops.”

- Import-licensing liberalization “has led to a 20 percent drop in the price of clothing items and a 35 percent drop in the price of home appliances.”

Be still, my beating heart.

That said, Milei still faces big hurdles—economically and politically. As already noted in the stats above, for example, inflation and poverty in Argentina remain too high, and employment and wage growth are too low. In housing, meanwhile, Bourne notes that evictions are still too difficult—“the process requires a judge’s order following a lengthy trial, which … can drag on for up to 18 months”—and thus many potential landlords remain on the sidelines. The Financial Times adds that domestic manufacturing continues to struggle, which local companies attribute to taxes that are still too high and labor markets still too rigid. Even with a much needed International Monetary Fund loan on the horizon, there’s still plenty in Argentina that can go wrong.

That’s especially true given the politics and the caution that Milei thinks they demand. As noted, one of the biggest reasons why Milei’s Year 1 reforms weren’t more dramatic is that he’s been hamstrung by left-wing political opposition—both labor and student protests in the streets and a Peronist movement that still holds almost half of the senate. That won’t change until at least this fall, and big risks remain in the meantime.

Summing It All Up

In a little over a year, Javier Milei and his ragtag team of budget-cutters and deregulators have put one of the world’s true economic basket cases on the path toward fiscal sustainability and economic growth. Through a long series of piecemeal reforms—some painful “shock therapy,” yes, but also a lot of pragmatic (and incomplete) stuff too—they’ve gotten inflation, poverty, and unemployment down; growth, wages, and trade up; and trends for this year looking even better. And they did it all with limited legislative representation and support.

As a result, the goofy-looking guy who last January was shunned by the proverbial global elites in Davos was being feted there just 12 months later.

There are, of course, many hurdles left for Milei and Argentina to clear in the months ahead. Not even a popular, chainsaw-wielding economist can wipe away decades of terrible economic policy—and epic political mismanagement and corruption—overnight, especially when large swaths of the government are enriched by the status quo and dead-set against reform. Additional cutting—of spending/debt, domestic regulation, capital controls, trade restrictions, state-owned enterprises, and more—is needed. And Argentina’s brittle economy might still break before market-oriented reinforcements take hold, thus ensuring that much-needed legislative support never arrives.

In the meantime, however, one thing is clear: Milei has demonstrated the legitimacy of not just his work in Argentina but of real-world libertarianism more broadly. On the economics, Argentina provides fresh proof that “radical” efforts to shrink the state and liberate markets can be strategic, intellectually serious, pragmatic when needed, and remarkably effective in a short period of time. The efforts can turn skeptics who once predicted economic collapse, as GZero’s Ian Bremmer famously did back in 2023, into reluctant believers (“It’s quite possible we’ll be looking at an even more triumphant Milei at Davos 2026.”) And they can provide a template for real reform—not just slogans and memes—in developing and developed countries alike. (DOGE, please take note.)

The political success of “The Madman” might be even more consequential. Even after all the deep cuts, anti-government rants, and longwinded economics lessons (no, really!), Milei’s approval rating has remained high, and his new Libertad party has consistently led in legislative polls. Per Gallup, Argentines—rich and poor—now report being more optimistic about their economic future and living standards and more confident in their government and president. And after spending some time in Argentina recently, Vásquez notes a clear cultural shift “away from the socialist and statist ideals that created the Argentine crisis and toward one that is supportive of civil society and the principles on which it relies.” Just as remarkably, he told me last week, this shift is happening elsewhere in Latin America, with similar candidates popping up in several countries and promising real free-market reforms.

These trends run starkly against the conventional wisdom that openly libertarian policies succeed only in college textbooks, or—even worse—that they’re found today only in failed states. That stuff always rang hollow, given the veins of free market thought running through economic policies around the world, but Milei’s frontal assault is fundamentally different in size, scope, and volume—and thus more important. As I wrote in early 2024, Milei’s ideas and challenges made his policy work “some of the most relevant—for better or worse—reforms undertaken anywhere in the world.” So far, it’s been undeniably for the better for Argentina and free marketers everywhere.

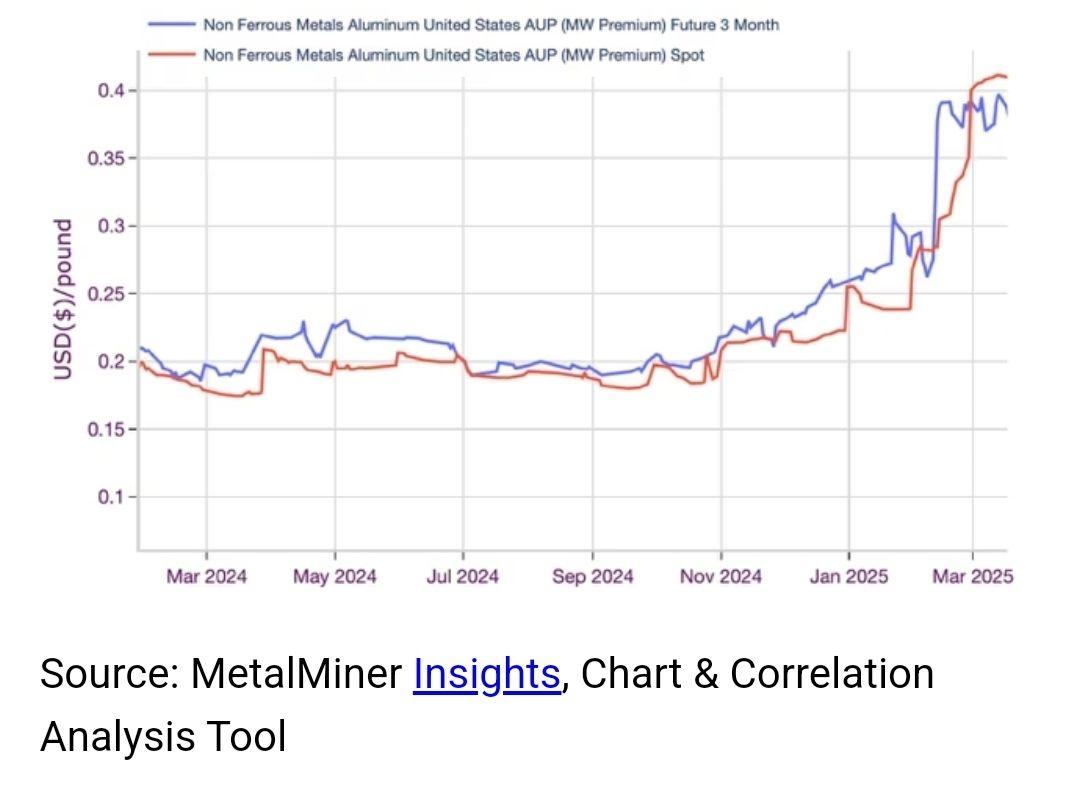

UPDATE, March 27, 2025: Shortly after this piece was published, Capitolism HQ received perhaps the most important and relevant news out of Argentina yet:

I’m not saying correlation is causation here, but—given the timing—I’m also not saying it’s not.

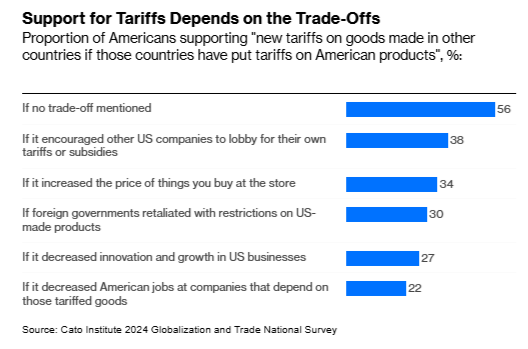

Chart(s) of the Week

The Links

“Proposed US port fees on China-built ships begin choking [US] coal, agriculture exports” (new study)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.