As fire still rages in the Los Angeles area, I’ve been torn about whether to write about it. Beyond the very real tragedies and my general rule against public dunking, a lot of what’s going on out there has nothing to do with policy. As our friends at The Morning Dispatch explained, for example, national experts and folks on the ground seem to agree that the unfortunate and freakish confluence of several meteorological phenomena—especially the hurricane-force winds and recent lack of rain—made much of the damage in and around L.A. unavoidable regardless of the policies in place or the people in charge. And much of the knee-jerk, partisan hysteria surrounding the fires has proven to be premature, half-baked, or just plain wrong—not to mention distasteful.

On the other hand, there do appear to be several policies that, while they didn’t cause the fires, probably made things in L.A. today worse than they’d otherwise be—perhaps by a significant margin. They fit squarely within the stuff we talk about all the time here at Capitolism and provide lessons about not only the L.A. fires but also how (ostensibly) good policy intentions can generate really bad outcomes, thanks in large part to some equally bad incentives for all the people involved.

Insurance Regulation and the Distortion of Risk

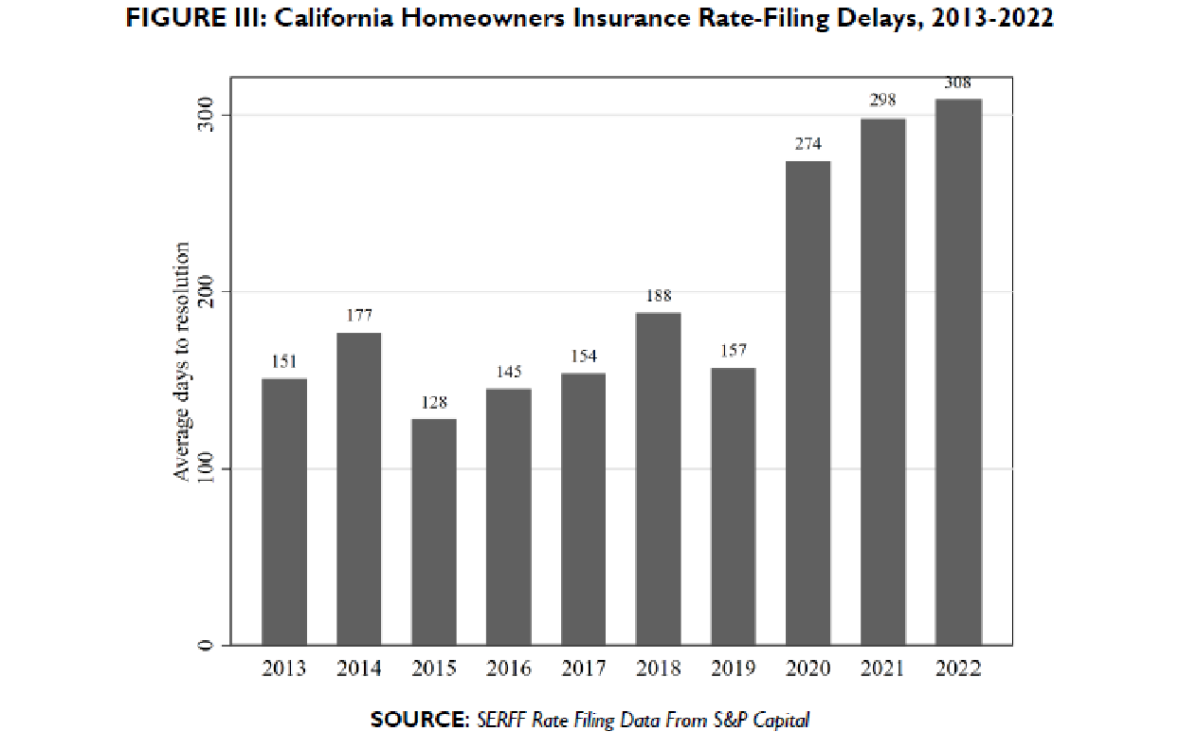

The place to start is California’s onerous regulation of homeowners insurance, which has probably encouraged many Angelenos to live in more fire-prone areas and has kept many of them underinsured or without insurance entirely. As economist Brian Albrecht detailed last week, citing a deep dive paper from his colleagues at the International Center for Law and Economics (ICLE), California’s Proposition 103 forces private insurers to price their products not just below hypothetical market rates but well below their cost—creating “the biggest gap between rates and risk in the nation.” Albrecht adds that the system is also highly inflexible and insanely slow: California’s speed of rate approvals ranked second-to-last among the 50 states (and D.C.) over the last five years, with an average of 236 days for homeowners insurance. And it’s been getting worse:

As my Cato Institute colleague Ryan Bourne detailed on Friday, this system creates two big and all-too-common problems accompanying price controls. First, it encouraged Californians to live in dangerous areas and to do so without adequate protection:

Market prices … serve as signals, telling homeowners, policymakers, and developers about the true costs of building and living in wildfire-prone areas. By capping insurance rates below what market conditions demanded, California muted these warning signals for some homeowners, forcing companies to price below expected cost and making consumers feel safer than they were. This encouraged development in fire-prone areas and reduced the incentive for homeowners to, say, purchase supplementary private fire insurance services.

Per M. Nolan Gray, in fact, “From 1990 to 2020, California built nearly 1.5 million homes in the wildlife-urban interface [WUI], putting millions of residents in the path of wildfires.” (Prop 103 passed in 1988.) James Meigs adds that “more than a quarter of the state’s residents—roughly 11.2 million people—live in fire-prone WUI regions,” and “the explosion in WUI construction has dramatically expanded the scale of economic losses—the disaster ‘bullseye’—when wildfires ravage those areas.” Surely, many Californians would live in these places regardless of their insurance rates—but, if required to pay the WUIs’ real risk premium, many others probably wouldn’t.

For homeowners who still would choose to live in these places, moreover, exposure to the actual level of risk there might encourage them to deploy other measures to protect their property (and maybe enjoy savings on market-priced insurance in the process). They might, as the Los Angeles Times recently documented, employ private firefighting companies that have long operated in California to effectively put fires out or prevent them from ever starting—a “win-win” scenario for their clients because “the homeowner keeps their home and the insurance company doesn’t have to make a hefty payout to rebuild.” Homeowners in risk-prone areas might also be more inclined to pay for fire-resistant construction materials, designs, and landscaping—preventative measures, Bloomberg reports, that have saved many homes in the L.A. area this past week. (Commercial ones too.)

In this light, Prop 103 operates a lot like our totally screwed-up system of flood insurance on the East and Gulf coasts, which both encourages Americans to build and live in coastal areas frequently ravaged by hurricanes and inflates the damage tally when storms hit. As National Review’s Dominic Pino puts it, California’s regulations have given Angelenos a short-term win in the form of cheaper insurance, but at a potentially huge—fatal, even—long-term cost “by destroying the signals that prices are supposed to convey, especially the price signals about wildfire risk, it has placed more property in harm’s way than would otherwise be the case.” Indeed.

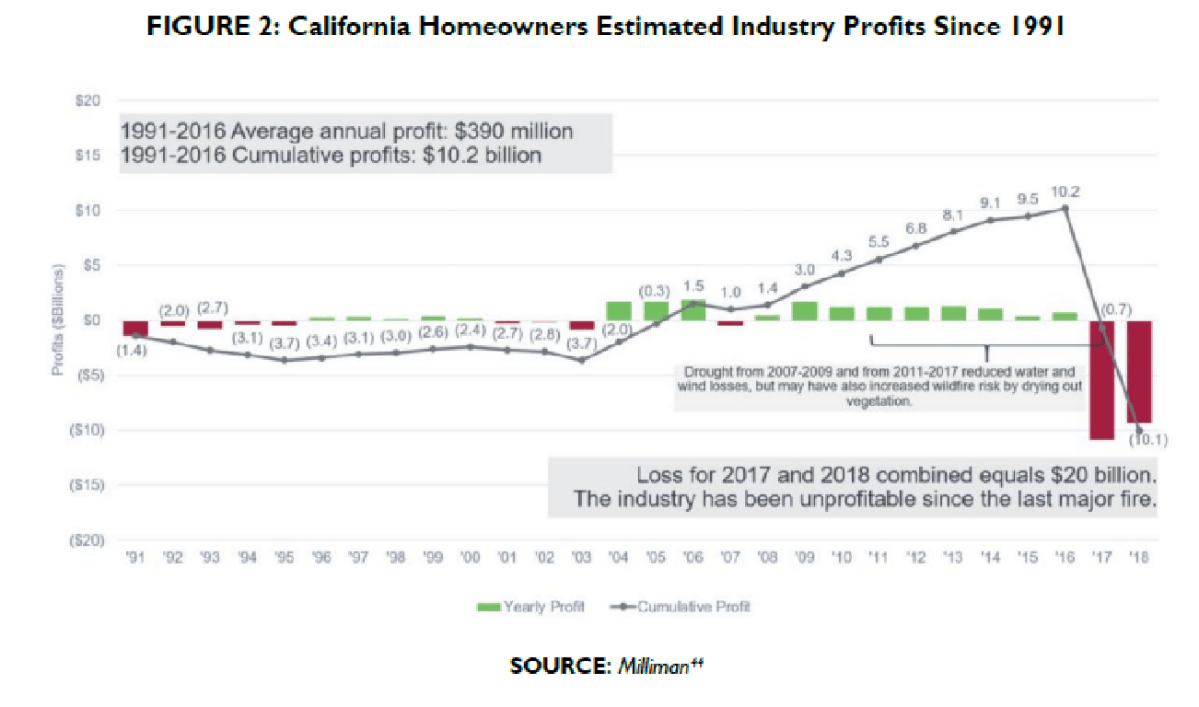

The second big problem is that—by barring private insurers from charging market rates and adjusting quickly to new market conditions—California’s insurance regulations have pushed private insurers out of high-risk areas or out of the market entirely. Citing the ICLE’s data, for example, Pino notes that California home insurers lost more in 2017 and 2018 ($20 billion) than their total for the previous 15 years combined:

With no way to recoup these losses or better hedge against future ones, many private insurers have left the California market or refused to issue or renew policies there—including for people hit by the L.A. fires. As Bourne notes, for example, “State Farm announced plans to non-renew tens of thousands of policies in high-risk areas like Pacific Palisades, where 69 percent of properties were dropped.”

With no standard private insurance available, millions of California homeowners have turned to alternative insurers or the state’s bare-bones, last-resort FAIR plan. But this raises further problems. The former is typically available to only the wealthy, while the latter caps losses at $3 million—a relatively low amount for this part of California (sigh). The FAIR plan also is now exposed to massive fiscal losses—-almost $500 billion statewide and tens of billions for the L.A. fires alone—that the state might have to recoup from private insurers. That, in turn, would penalize low-risk customers (via higher rates) and further pressure the already brittle system. Federal dollars are also in play—thus putting us all on the hook for these disasters (and for California homeowners’ distorted decisions).

Collectively, any such rescue not only raises fairness concerns but feeds back into the first problem Bourne and Pino identified: If people can obtain FAIR coverage in the highest-risk areas or get bailed out after things go terribly wrong, they’re more likely to live in those risky places—and more likely to forgo future spending on fire mitigation, supplementary insurance, or private protective services. It’s a classic case of moral hazard that’s bad for the current fires and for future ones.

Public Land Management

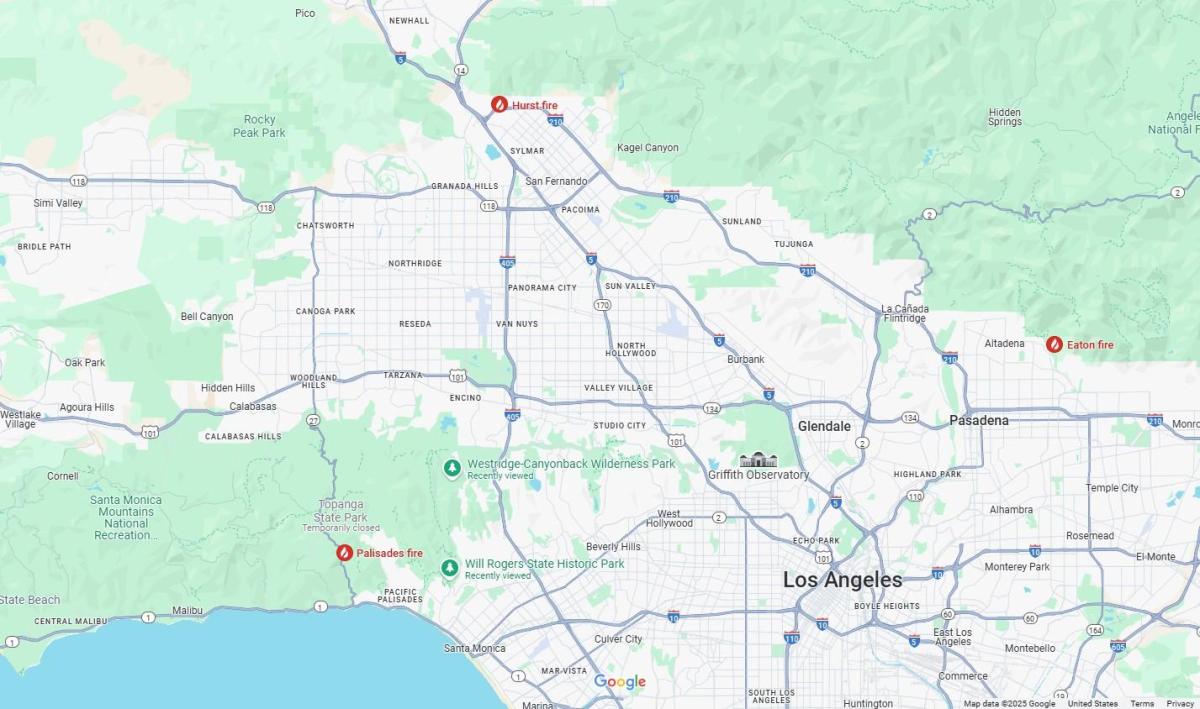

The immense amount of government-owned land in and around L.A. likely creates another problem, this time for wildfire mitigation. As National Review’s Jim Geraghty astutely pointed out last week, the main fuel source feeding the L.A. fires is “Southern California chaparral and coastal sage scrub,” which cover much of the area, “ignite easily, burn intensely and spread rapidly.” Private landowners in L.A.’s “Very High Fire Hazard Severity Zone” are required to clear vegetation away from structures, fences, and roads to keep fires from spreading. Enforcement of these rules may turn out to be an issue, but the more fundamental one is that a huge chunk of Los Angeles County isn’t privately owned:

The county has roughly 900,000 acres of protected public lands, an area larger than the state of Rhode Island — 34 percent of the total land area. In fact, more than 64 percent of the county’s land is classified as a “natural area,” meaning there are few structures on it. It is a vast county of densely packed valleys and towering hills and mountains covered in chaparral, alongside sizable state parks and national forests.

Among these public lands is the Angeles National Forest, which is managed by the U.S. Forest Service and covers about a quarter of L.A. County. Another federal property, the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area (SMNRA), managed by the National Park Service, consists of another 158,000 acres, and numerous state and local parks cover even more area:

As the above map shows, many of these public lands border the places in L.A. County burning today (red dots). And people are starting to question whether government managers of these areas did an adequate job of mechanical brush clearing and other fire mitigation measures, such as controlled burns or even using goats and sheep to eat away at dry hillside vegetation. As Geraghty notes, for example, Pacific Palisades developer and former mayoral candidate Rick Caruso alleged last week that hillside brush areas controlled by the city and the county “haven’t been handled, mitigated, pruned, removed for maybe 30 or 40 years.” Per the Wall Street Journal, city officials have vehemently denied such allegations, but Caruso isn’t the only one who’s noticed a problem in public areas:

Jennifer Gray Thompson, CEO of After the Fire USA, a California nonprofit that helps towns rebuild after disasters, said she could see the lack of brush management by L.A. County in a visit with the fire chief of Beverly Hills last year. “You could clearly see where L.A. County property began, full of chaparral,” Thompson said via email. “BH? Mitigated.”

Others, such as the New York Times’ David Wallace-Wells have similarly acknowledged that “the job of brush clearing and fuel thinning has been neglected around Los Angeles."

How much of a difference such efforts would have made in L.A. remains a hot source of debate. According to the L.A. Times, some experts claim better brush clearance on public lands would be moot in these extreme weather conditions, where high winds can cause embers to travel long distances, but other experts disagree:

Joe Ten Eyck, who coordinates wildfire and urban interface programs for the International Assn. of Firefighters, said extreme weather conditions can make brush clearance even more important. “The more we take away the fuel for a fire to burn, the more we’re going to lessen the risk and make individual residences and communities resilient,” said Ten Eyck, who is also a retired operations chief with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

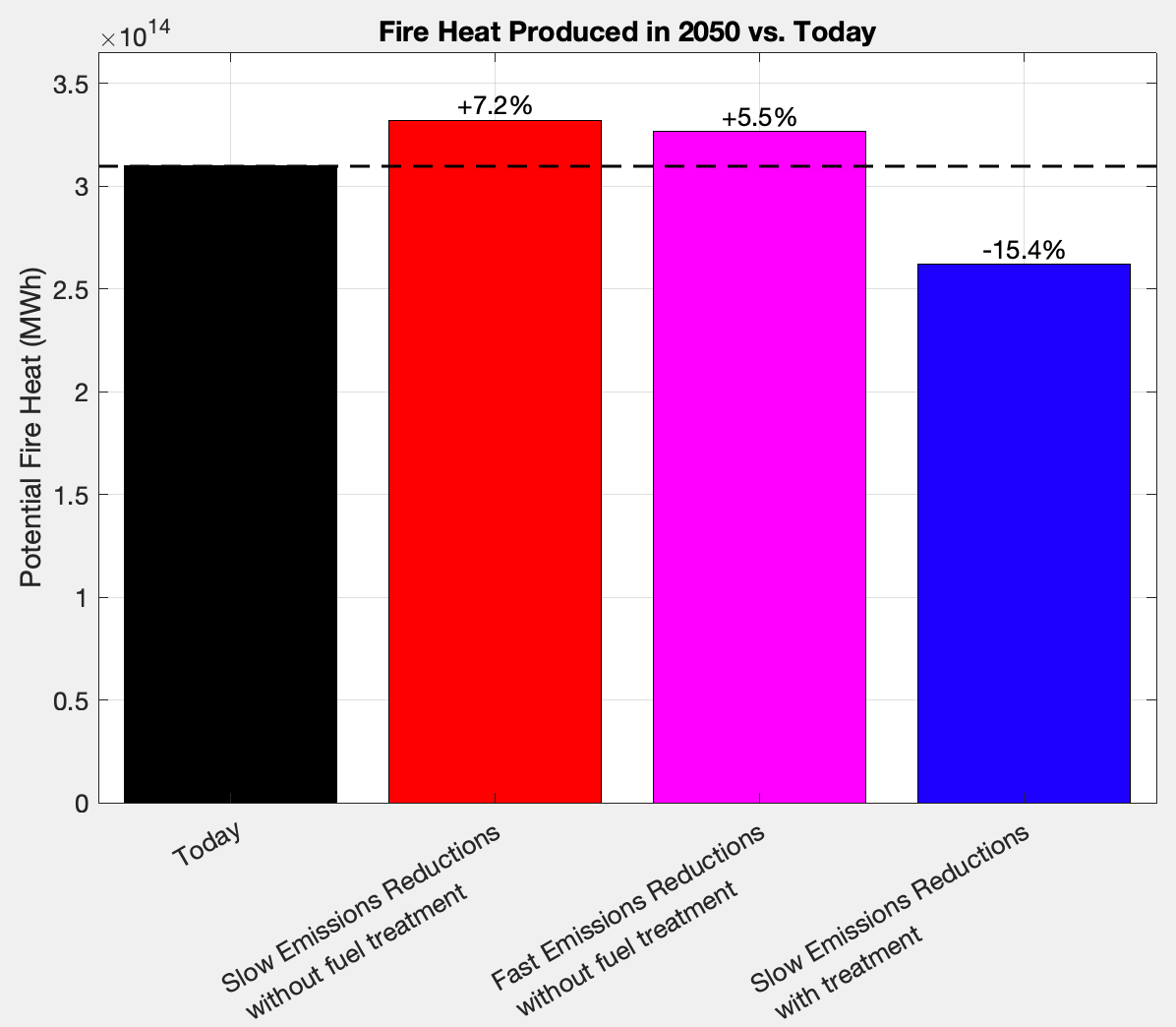

Ten Eyck isn’t alone in this view, and various anecdotes support it. Per the Times, the famed Getty Villa was just saved thanks in large part to its “pruned landscaping,” and Ventura County’s strict brush clearance rules “helped firefighters defend homes from the Kenneth fire that spread through the West Hills area Jan. 9” when winds were almost as strong. (Ventura County appears to have contained a brand new fire, too.) Other places nearby, such as Pepperdine’s sprawling campus in Malibu, have also avoided the worst via similar mitigation measures. Overall, the Breakthrough Institute calculates that, even assuming the harsh weather in Los Angeles this past week and a warming planet in future years, better vegetation reduction could reduce fire intensity by more than 15 percent:

It’s too early to confidently say that poor government land management added to the scale and intensity of the L.A. fires, but it wouldn’t be a surprise if it did. As the aforementioned Journal piece notes, for example, governments’ failure to clear brush “has been an issue in other big wildfires,” including the 2023 fires in Hawaii—a “catastrophic fire spread” fueled by unmanaged vegetation that both Maui County and Hawaii state officials ignored for years.

Such neglect, in turn, stems from at least two issues unique to government-owned land in the United States. First, public ownership subjects mitigation treatments to a thicket of additional rules and regulations. As Hannah Downey of the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) explained before the House Natural Resources Committee last year:

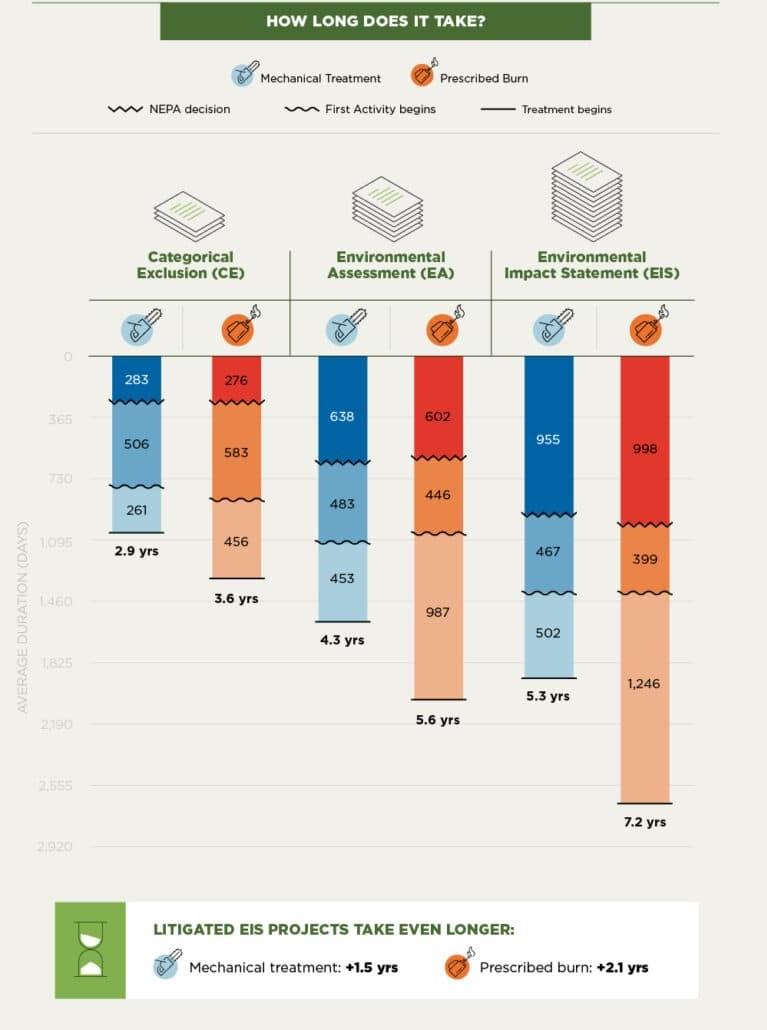

Before any chainsaws or drip torches can touch a federal forest, a restoration project must navigate complex bureaucratic procedures, including review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Depending on the extent of anticipated impacts, NEPA may require the Forest Service to analyze a project through, in order of increasing complexity and expense, a categorical exclusion, environmental assessment, or environmental impact statement. The agency may also need to develop a range of alternatives to the project and analyze their impacts as well.

Her PERC colleagues thus estimate that it takes three to seven years to begin a mechanical treatment on the ground or a prescribed burn on federal lands, depending on the action and process. Litigation can add a couple more.

In California, the Breakthrough Institute folks note that this kind of regulatory bottleneck has long been a problem for wildfire mitigation. The state’s “mini-NEPA,” the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), poses “additional bureaucratic and regulatory obstacles to clearing hazardous materials on state land.” Other experts have recently noted the same problems.

Second, public land ownership distorts the incentives to perform mitigation work even after the regulatory hurdles are cleared, and here, again, there’s some evidence this was a problem in L.A. In particular, Kevin Drum explained over the weekend that, while the aforementioned regulatory impediments “are real for both prescribed burns and mechanical treatments,” the bigger obstacles lie elsewhere, including “public opposition” to mitigation and “the risk-averse views of forest managers” who are wary for both technical reasons and fear of public backlash. Stanford’s Michael Wara provides the killer quote in this regard (emphasis Drum’s):

“If there’s a prescribed fire and it goes wrong, someone’s in trouble,” Wara said. In this case, it’s the federal government, which is on the hook for billions in recovery costs. “But no one in the Forest Service gets in trouble when there’s a wildfire that destroys communities and destroys a landscape, and the fire really occurs because of the lack of management over decades,” Wara said.

This kind of extreme risk aversion is common in government and something we (unfortunately) see all the time with new drugs, as regulators are strongly incentivized to obsess over the seen risks of drug approval and to ignore the unseen, and potentially much larger, costs of not doing so—the so-called “Invisible Graveyard.” In the context of wildfire prevention, the same incentives mean that government administrators can take years to carry out prescribed burns, and that less mitigation gets carried out overall. And studies show that “the federal government has a poor record of ecological stewardship” overall.

Privately owned lands, by contrast, are less susceptible to these problems. They’re less burdened by regulations like NEPA/CEQA, and private landowners are also less likely to be swayed by public opinion regarding things like scenery or temporary smoke. Because these same individuals have a direct interest in their property’s long-term survival, moreover, they’re highly motivated to ensure that it’s not destroyed by fire or any other natural disaster. (I think this was even an episode of Yellowstone, lol.)

Sometimes, this stewardship is carried out by mission-driven conservationists. In a Cato podcast last month, for example, Downey told the story—confirmed elsewhere—of a raging, out of control fire in Oregon that was stopped dead in its tracks, thanks to the mitigation efforts (mechanical thinning and prescribed burning) of its owners, the private nonprofit Nature Conservancy.

Other times, however, private fire protection is profit-oriented, as evidenced by Northern California timber companies that cleaned up underbrush and replanted saplings, thus limiting fuel buildup and big wildfires. As University of California-Merced’s Crystal A. Kolden explained last week, the now-burning public lands around L.A. faced a similar dynamic, as clearing once done by livestock ceased after the places became government-managed parks:

Until the 1960s, much of Santa Monica Mountains was still ranched, including what is now Topanga State Park that surrounds Pacific Palisades. Ranching is an active land use where grazing animals consume fine fuels and reduce shrub growth. That stopped when the SMMNRA and Topanga SP were established.

Since then, demand from residents and other hurdles have limited brush clearance in these public areas:

Over time, vegetation grew. Fires burned, again and again, but not everywhere because we suppressed them. Recreational users liked being in nature with tall shrubs and trees along canyon bottoms to block out the hot sun. Homeowners liked nature and privacy, and they planted landscaping that matched. The county and state know this area has high fire risk, and they've done several veg reduction projects in recent years to try and address it. But prescribed fire is almost impossible to do here bc of complexity, manual labor is expensive, and there are numerous restrictions in conservation areas.

None of this means that the feds should sell off Yosemite tomorrow or anything, but it does provide yet another reason for public lands near major metro areas to be auctioned off—and for us to suspect a lack of sufficient wildfire mitigation around L.A. in recent years.

Other Potential Problems

Other policies might also have played a role in the fires, though their direct impact is more debatable. This includes land use policies that, per Gray, make it more expensive to build and live in parts of L.A. that are more fire resistant:

Policy didn’t just pull Californians into dangerous areas. It also pushed them out of safer ones. Over the past 70 years, zoning has made housing expensive and difficult to build in cities, which are generally more resilient to climate change than any other part of the state. The classic urban neighborhood in America—carefully maintained park, interconnected street grid, masonry-clad shops and apartments—is perhaps the most wildfire-resistant pattern of growth. By contrast, the modern American suburb—think stick-frame homes along cul-de-sacs that bump up against unmaintained natural lands—may be the least. Several of L.A.’s hardest-hit neighborhoods resemble this model. Infill townhouses, apartments, and shops could help keep Californians out of harm’s way, but they are illegal to build in most California neighborhoods. And even where new infill housing is allowed, it is often subject to lengthy environmental reviews, which NIMBYs easily weaponize. And if you want to build anywhere near the coast—the only part of greater Los Angeles not currently under a red-flag warning—prepare for months of added delays.

The extent and effect of land use problems are unclear, given that many Californians probably prefer to live in WUIs—at least if they don’t have to pay for it. In that regard, Meigs notes another way that California policy implicitly encourages Californians to live in these high-risk areas (emphasis mine):

California continues to nudge its citizens out of dense regions (which are relatively safe from fire) and into more vulnerable terrain. In fact, while urban dwellers face sky-high costs and declining services, residents of the WUI often benefit from hidden subsidies. For example, while living in fire country entails higher risks, California funds a massive firefighting program focused mostly on protecting residents and their homes. These efforts are not always successful, of course, but the state’s firefighters usually succeed in keeping fires from reaching developed areas. Knowledge that homes in the WUI are likely to be protected (at no cost to the homeowner) constitutes a huge, if hidden, subsidy. Two economists who studied this phenomenon concluded that the state’s firefighting investment boosts WUI home values and effectively bankrolls “development in harm’s way.”

Water policy also appears to be a problem. As PERC’s Shawn Regan explains (h/t J.D. Tucille), California law encourages overuse and discourages conservation, thanks to price controls, subsidies to politically powerful farmers (who account for 80 percent of California water consumption), restrictions on and litigation over water trading, and “use it or lose it” rules that push farmers to use their full water rights allocation to avoid losing it in the future, regardless of weather or market conditions. Bad policy and environmental regulations also have thwarted efforts to boost water supply and storage capacity through things like desalination plants and storage infrastructure. On the former, Marc Joffe notes that Israel has less coastline than California yet treats 400 million gallons of seawater per day. (California does a fraction of that.) Regan adds that the state hasn’t built a major new reservoir in more than 40 years; environmental rules prevented recent floods from refilling the depleted ones that already exist; and even groundwater storage and rights are routinely confounded by California law. These policies didn’t directly cause L.A. fire hydrants to run dry, but they did make water in California less available than it ever needed to be, including for emergency purposes.

Summing It All Up

As many people have rightly noted, fire has long been an issue in California, and recent days’ freakish weather conditions all but ensured that fires would rage around L.A. and that damage would be significant. But those facts don’t mean that the situation out there isn’t worse—in terms of damage, cost, and possibly severity too—because of policy. Would as many homes have been destroyed if government insurance policy let private providers adequately price the risk of living in fire-prone places, or if housing/fire policies didn’t push/pull Californians to such places? Probably not. Would the fires have burned as far and wide if certain public lands were put in private hands for development or grazing or conservation, or if water policy promoted abundance instead of shortages? Probably not. And would the cost of rebuilding and recovering from the fires be as high if these and other policies had been reformed as so many people have suggested? Probably not!

To be clear, none of this is about Gavin Newsom or Karen Bass or the Democratic Party or even the state of California (though the officials’ initial responses leave much to be desired). Prop 103, for example, was approved by referendum decades ago; insurance price controls were recently supported by California’s Republican candidate for insurance commissioner; and, as Bourne has documented, politicians’ War on Prices has raged in many other states and localities too. Instead, it’s about understanding how policy affects incentives; how incentives affect our decisions; how those decisions affect not just costs and conveniences but sometimes even life and death; and why we should urgently improve bad policies, in California or anywhere else.

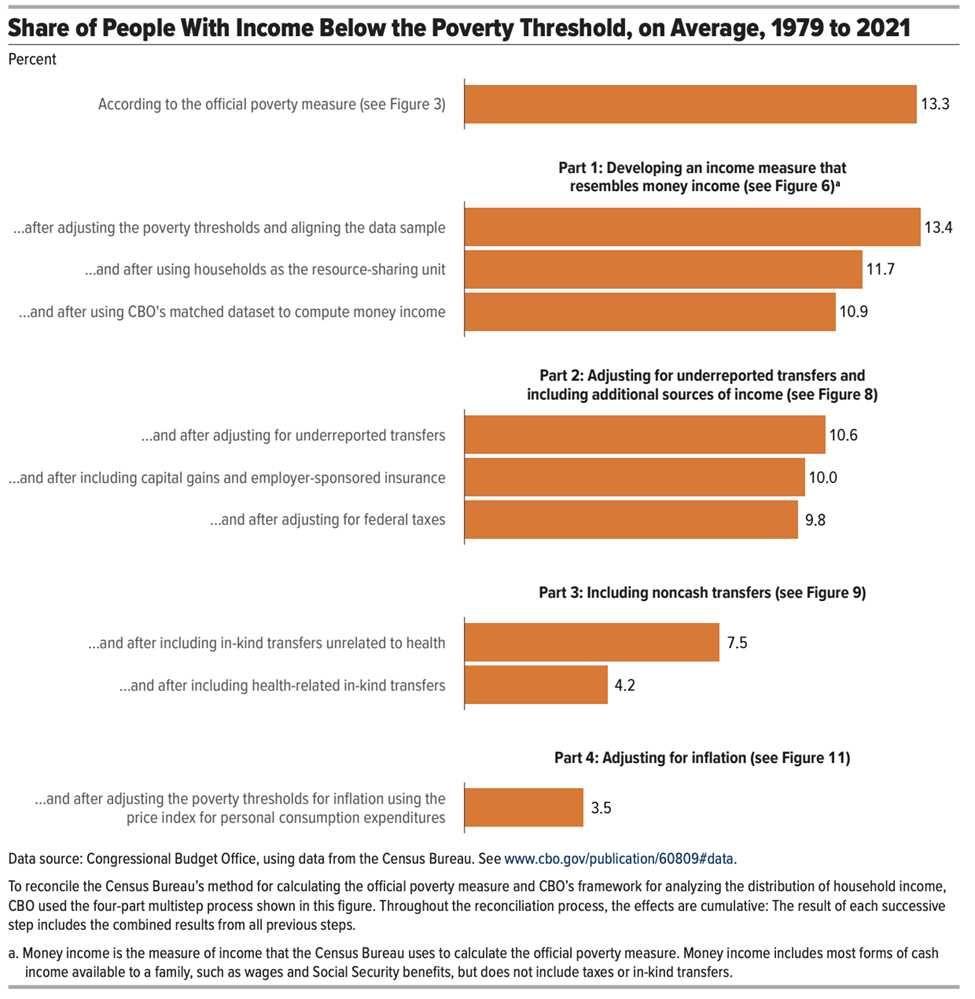

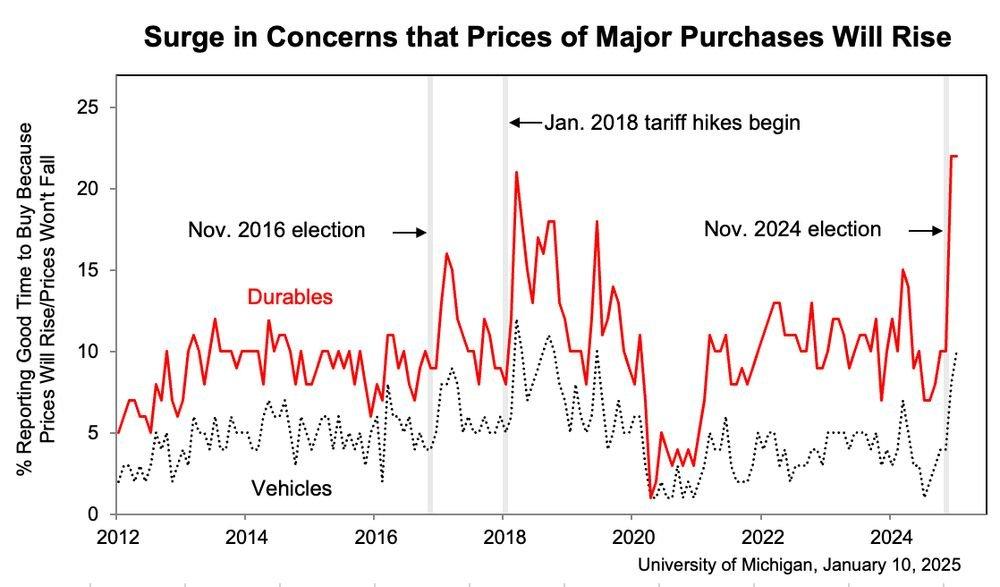

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.