While Capitolism was vacationing, avowed socialist Zohran Mamdani scored a surprising victory in New York City’s Democratic mayoral primary—one that’s thrust many of his state-centric proposals into the spotlight. Among those is his very bad plan for government grocery stores, which—as the Unofficial Newsletter of American Grocery AbundanceTM—Capitolism is effectively obligated to cover.

For today’s purposes, I’ll avoid the obvious Soviet breadline jokes and even ignore that—per the Washington Examiner’s Tim Carney—Mamdani appears to have embarrassingly botched how the city would pay for his experiment. (Insert even more commie jokes here.) His eagerness to pursue the system once in office is also somewhat unclear. Yet the grocery proposal remains noteworthy both for its massive weaknesses and what it says about those still championing it today. In that sense, Mamdani’s grocery plan is a classic example of a statist hammer—and in this case sickle (sorry I couldn’t resist just one)—in search of a “market failure” nail.

There’s No ‘Grocery Problem’ To Be Solved

As my Cato Institute colleague Ryan Bourne helpfully summarized before the election, Mamdani has proposed a pilot program of five city-run supermarkets, one in each borough, to improve New Yorkers’ access to low-priced groceries—especially in so-called “food deserts” that lack healthy options. To achieve these goals, the stores would 1) operate on a nonprofit basis, buying and selling at wholesale prices; 2) be located on city-owned land (to avoid recurring rental payments); and 3) reduce transportation costs by utilizing centralized logistics and sourcing from local neighborhoods. Then, BOOM, socialist food paradise (or something).

As a non-paying reader, you are receiving a truncated version of Capitolism. You can read Scott’s full newsletter by becoming a member here.

Yet there’s no reason to think Mamdani’s public supermarkets would effectively combat food inflation or help American grocery consumers. For starters, new USDA data show that Americans’ spending on groceries (“food at home”) has—after a rough couple of post-pandemic years—resumed its historic decline, while overall food inflation has moderated, too.

As Bourne notes (and as Capitolism has explained repeatedly), moreover, there’s no indication that a state-run option might be needed because American supermarkets are enjoying windfall profits at consumers’ expense:

[G]rocery stores make very small gross profit margins, typically 1–4 percent, and operate in fierce localized competition with a range of food outlets. Even on a simplistic static basis, then, the scope for price cuts and across-the-board discounts to customers is tiny. A municipal operator could forgo profit, but the room that creates is only one-or-two cents on every dollar of sales.

He adds that public grocery stores would also lack the scale, sophistication, and efficiency that Big Grocery deploys to achieve low prices and stay in business, and that these weaknesses ruined past government attempts to run grocery stores in rural Florida and Kansas—tiny places that, The Atlantic documents, had literally no other grocery options for miles.

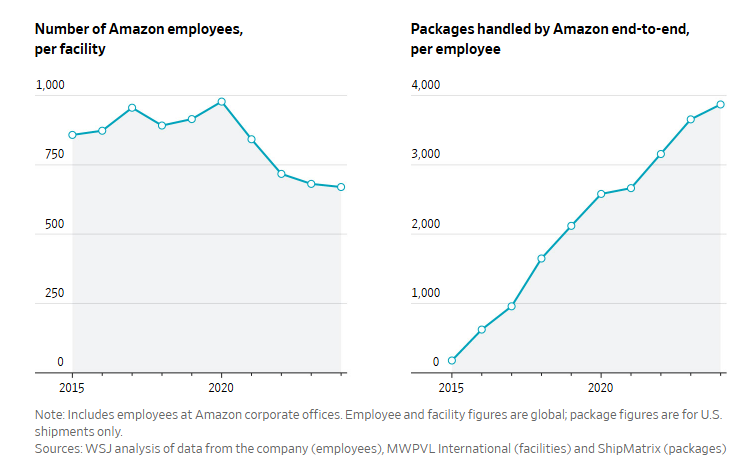

As we discussed in February, moreover, the U.S. grocery market is dynamic, diverse, and full of innovative new entrants eager to gain new customers and steal market share. Thus, traditional supermarket giants like Kroger and Albertsons have been steadily losing ground to newer, less-traditional players like Walmart, Costco, dollar stores (including their grocery spinoffs), Amazon and other online players, and Aldi, which is now the third-largest grocery chain in the country. The idea that there’s a broad “market failure” in the U.S. grocery business is simply ludicrous.

The “food deserts” justification is similarly misguided. As Matt Yglesias explained for Bloomberg, there’s no good case for adding supermarkets—public or otherwise—to improve public health in New York or anywhere else. For starters, research (“study after study after study”) consistently shows that there’s a weak, if any, linkage between a neighborhood’s access to healthier foods (including at grocery stores) and their eating habits or overall health. One particularly noteworthy study found that opening a government-subsidized supermarket in Philadelphia—part of Pennsylvania’s “Fresh Food Financing Initiative”—had no noticeable effect on locals’ reported fruit and vegetable intake or body mass index. The findings thus “suggest that simply improving a community’s retail food infrastructure may not produce desired changes in food purchasing and consumption patterns.”

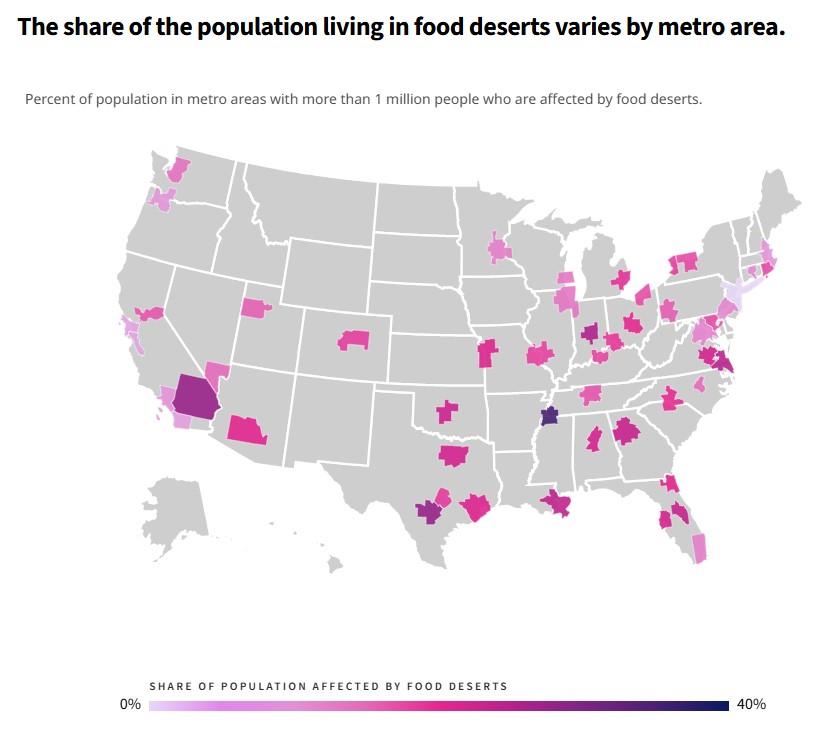

Even if more grocery stores could improve public health, moreover, New York City already has lots of food options—both online delivery services and brick and mortar grocery stores. A recent study, in fact, ranked the Big Apple the No. 1 U.S. metro area in terms of residents’ “equitable access” to a local supermarket, and found that the city would need only two new stores—yes, just two in all of NYC—to achieve an ideal level of grocery store access via a 10-minute walk or less. According to the USDA in 2021, moreover, the New York City area had just 3.5 percent of its low-income population living in supposed “food deserts”—one of the lowest shares in the country.

Thus, whether it’s food prices or food deserts, Mamdani’s proposal seeks to solve market “problems” that don’t really exist.

Creating New Problems

Then there are the new risks that municipal grocery stores would raise. Pointing to the $78 billion hole in New York City’s “deteriorating” public housing, for example, Bourne warns that putting New York City politicians in charge of supermarkets would probably mean higher costs and worse service, not the opposite. Offering food items below cost would also necessitate endless subsidies and—as we know from explicit price caps—risk empty store shelves, long lines, and illicit resale markets, while potentially pressuring private stores to leave the affected area (thus demanding even more city involvement!). Using city land for unnecessary public grocery stores also imposes opportunity costs, as it “means fewer resources and less space available for more productive public purposes like housing, schools, parks, or other essential infrastructure, or else a forgone sale or rental value that could be accessed to give money back to taxpayers.” And, of course, New York politicians would have a strong incentive to use these new enterprises for political gain, compounding the risk of cronyism, corruption, and inefficiency—as California politicians’ recent, union-backed crusade to ban self-checkout depressingly demonstrates.

Indeed, we can see many of these exact problems in the seven states in which the government directly owns and operates liquor stores, which some supporters of Mamdani’s idea have (bizarrely) cited to defend it. So-called “ABC stores” in these states are notorious for having subpar choice, operating hours, innovation, and service, while often operating at an inexplicable loss for the states at issue. (That a state liquor monopoly can lose money is a corollary to Milton Friedman’s classic line about government-run deserts.) These outlets also have repeatedly been found to waste taxpayer funds; to suffer from high operating costs, political favoritism, and outright corruption; and to vigorously resist needed oversight and reform (especially privatization or commercial/interstate competition). And the stores’ regulated prices predictably breed vibrant black markets, thus necessitating multistate sting operations and armies of “liquor cops” (171 in Pennsylvania!) to crack down on illicit transport and resale of price-controlled hooch.

Almost anyone living in a control state can attest to ABC stores’ awfulness, yet the systems persist because, as the Manhattan Institute’s Jarrett Dieterle documented in Virginia, they employ thousands of people (who are also voters), generate hundreds of millions of dollars in annual revenue for state and local coffers, and—in classic bootleggers-and-Baptists fashion—are often supported by both Big Alcohol and pro-temperance religious groups (not to mention local socialists). That’s an irresistible combination for the vast majority of state and local politicians, so these Prohibition-era relics remain—regardless of their consequences or consumers’ preferences.

The entire state liquor monopoly model, of course, was never intended to deliver low prices, wide selection, high quality, and more convenience—in fact much the opposite. Yet those things are exactly what we want from our supermarkets, and they’re something private players eagerly and successfully provide for a very modest fee. Injecting the state into such a system makes no sense.

Other, Better Alternatives

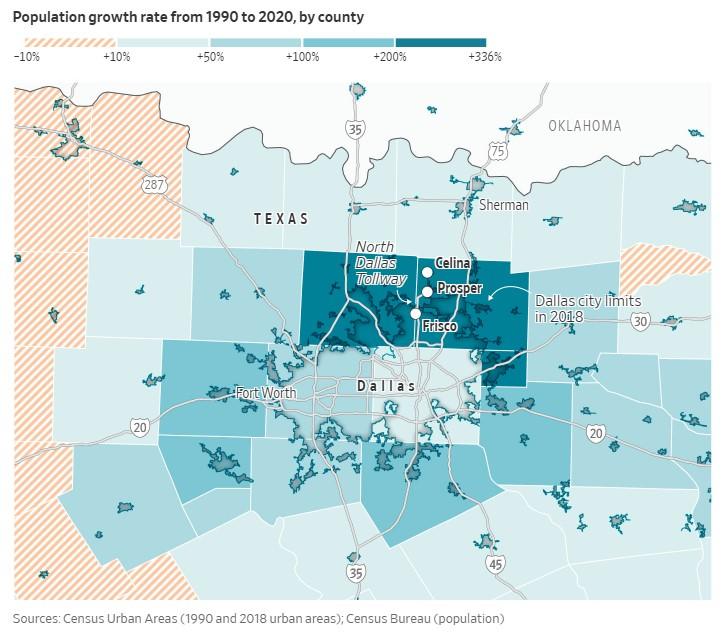

It’s particularly nonsensical given the simpler, better levers that local lawmakers could pull to encourage lower grocery prices and more supermarkets while also benefiting their communities more broadly. Yglesias notes, for example, that his urban neighborhood in Washington, D.C., gained a supermarket following an influx of new, more affluent residents, indicating that simply improving core municipal functions—policing, sanitation, infrastructure, etc.—would go a long way toward attracting both local demand for and supply of groceries.

Another obvious lever to pull is zoning, permitting, and land use reform, especially in urban areas that make building new housing and large commercial structures exceedingly costly and difficult (often due to local “NIMBY” opposition). In the Brooklyn neighborhood of Crown Heights, for example, longtime locals fought to save their small neighborhood market from being replaced by a big new commercial development, even though the new place would house an even bigger, better supermarket. (Nostalgia is a menace, folks.) Yet, as the New York Times documented last year, the new Brooklyn construction has seen costs explode and completion delayed for years by a local law requiring the developers to “provide, at minimum, half a parking spot for each housing unit; one parking spot for every 400 square feet of retail and art gallery inside; and one spot for every 300 square feet of space in part of the planned grocery store (the other part of the grocery store is exempt from parking, and we’re sorry but only a land use lawyer can explain this).” Given the building’s footprint, the rules forced the builders to excavate 14 feet underground, add structural columns to support the above-ground units, and even install dozens of mechanical car-stackers to meet the strict numerical quota. That all costs a lot of money, which new tenants—including that supermarket—will inevitably pay.

As the Times notes, these kinds of requirements aren’t limited to parking or to New York City, and they’re sure to boost costs and delay, if not scuttle, local construction projects. Parking spots alone can average anywhere from $10,000 (above ground) to $70,000 (underground) per space—a cost “that gets baked into what developers must recoup from tenants and buyers, whether they own a car or not.” Other rules and regulations raise similar impediments—especially ones that allow local politicians to deny permits for, or anti-development “community groups” to sue to stop the construction of, large commercial buildings like supermarkets.

Such restrictions, in fact, have helped keep price leader Walmart out of none other than… New York City (repeatedly).

Given its geography, businesses, and population, Manhattan will probably never be cheap, but simply reforming or eliminating these kinds of regulations and improving core municipal functions would still go a long way towards encouraging more and better grocery stores there—to the extent they’re even needed.

Summing It All Up

So, municipal supermarkets wouldn’t improve grocery prices or food deserts, neither of which are hugely important or problematic to begin with. And, if state ABC stores are any indication, these new establishments could easily make New York’s grocery market worse, sucking up scarce government resources, pushing out market-based options, or breeding cronyism and black markets (and new “grocery cops”?). If New York and other places need improved grocery options, moreover, many simpler and better policy fixes can do the trick while offering broader community benefits and avoiding government-linked pitfalls. Indeed, as economist Richard Sexton just napkin-mathed in the Wall Street Journal, simply allowing Walmart to operate in New York City could—assuming it provided similar cost savings as it does elsewhere in the U.S.—reduce New Yorkers’ grocery spending by thousands of dollars per year (along with plenty of other pro-competitive effects too).

Of course, these real solutions offend many New York politicians and their favored constituents (unions, NIMBYs, etc), not to mention avowed anti-capitalists, and they don’t offer nearly the level of state involvement—and political opportunity—that interventionist plans like government-run supermarkets would. So, we get those proposals instead—and imaginary “market failures” along with them—regardless of their clear absurdity and potential harms.

And when those plans fail, capitalism will again get blamed, and we’ll get even more bad ideas to fix the problems the previous bad ones caused.

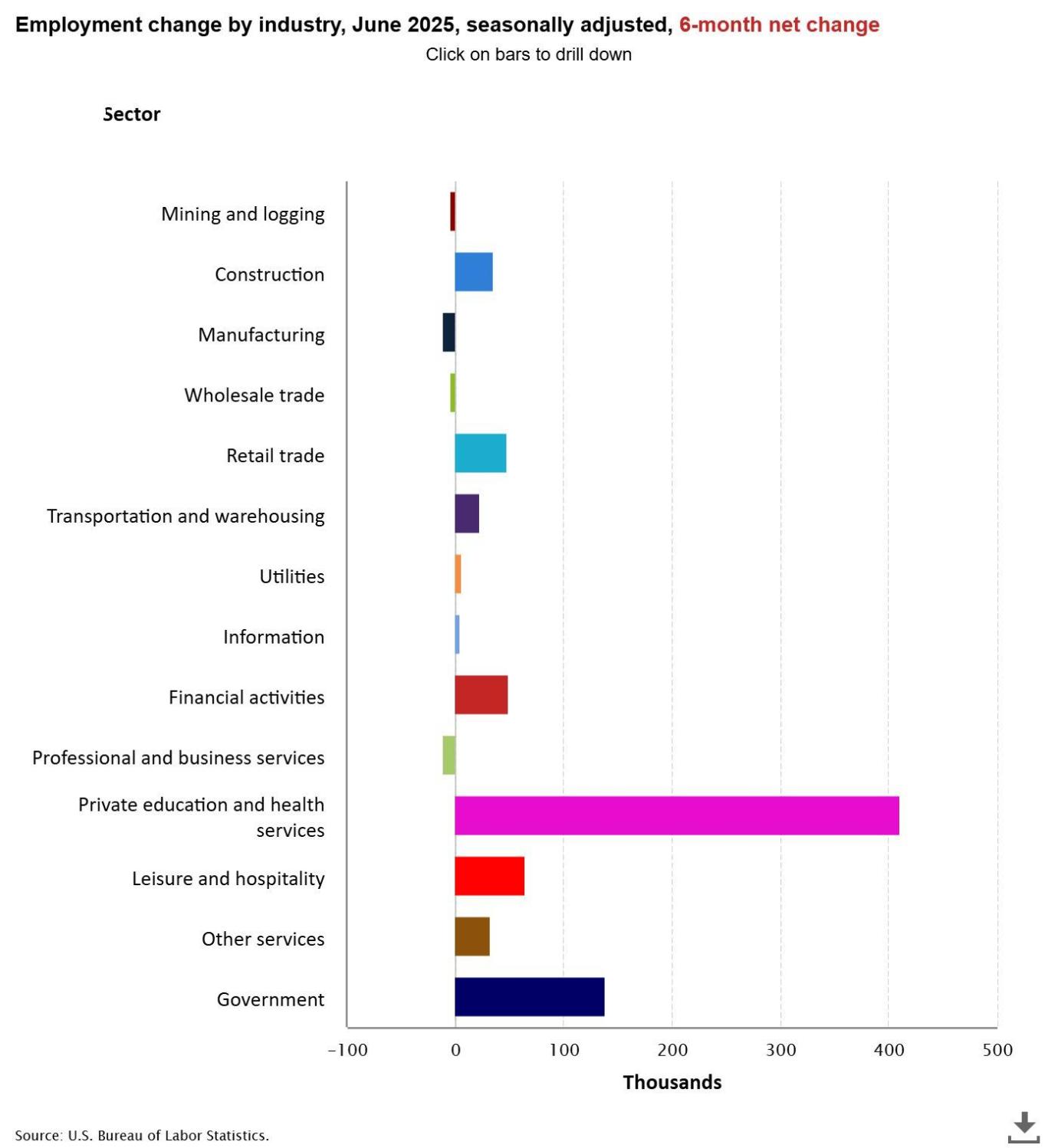

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.