One of this year’s more annoying yet persistent tariff defenses—including from a certain Oval Office Tariff Man and his trusty VP sidekick—is that tariffs can’t possibly be bad for American consumers or the U.S. economy because they haven’t caused “inflation.” In fact, a string of moderate 2025 reports from the two most common U.S. inflation gauges—the consumer price index (CPI) and the personal consumption expenditures price index (PCE)—have elicited victory laps from tariff defenders and even a detailed report from the President’s Council of Economic Advisers supposedly showing that the U.S. tariffs Trump imposed this year simply haven’t generated the “inflationary” pressures that tariff critics hysterically predicted. Tuesday’s new CPI print, which covered June and came in about where everyone was expecting, elicited more of the same, as did yesterday’s less-salient producer price index, which Vice President J.D. Vance jumped on to suggest “the economics profession doesn’t fully understand tariffs.”

So, has Trump proven the “experts” and “economists” wrong once again?

In short, no. Even leaving aside the wonky methodological mistakes (and blatant cherrypicking) that Vance and others tariff defenders have made, their recent “inflation” obsession reveals either a fundamental cluelessness about how tariffs and “inflation” interact—and about how most actual “economists” view the issue—or a cynical belief that you’re clueless, too.

Today’s newsletter will hopefully remedy the latter ignorance but, alas, has little control over the former.

As a non-paying reader, you are receiving a truncated version of Capitolism. You can read Scott’s full newsletter by becoming a member here.

Start With the Theory

Capitolism briefly (and presciently) covered this issue last September in our big tariff-myth debunker, but since the debunking apparently didn’t take—and since this has become such a big talking point for Trump and other protectionists—it warrants elaboration. Let’s start with the theory.

As I noted back then (and later discussed with Jonah on The Remnant), most economists wouldn’t predict or suggest that tariffs—even big ones—will cause a major and persistent bout of “inflation,” which is understood to be a sustained increase in the price of everything that we consume (aka the “general price level”) or a decline in the value of the dollar unit. The government calculates the CPI and PCE—proxies for the macroeconomic phenomenon of inflation—by broadly surveying a basket of both goods and services, including many things like housing, health care, and recreation that wouldn’t directly be affected by tariffs (even global ones). Here’s a handy breakdown of the CPI from 2023:

As for why we have inflation, a simple rule of thumb is that it’s caused by “too much money chasing too few goods,” thus implying both demand-side and supply-side factors. Economists generally agree that the drivers of inflation are broad, economy-wide forces and policies—not narrower things like tariffs.

On the demand side, this mainly means monetary and fiscal policy (putting more or fewer dollars into people’s hands to spend and changing their incentives to spend those dollars)—and here tariffs will have little effect on “inflation” properly understood. Instead, economists expect tariffs to affect the relative prices of tariffed goods but not cause longer term “inflation” because, without changes to the monetary/fiscal policies, businesses and consumers 1) will pay more for tariffed goods and thus spend less on other things, thereby reducing overall demand therefor (meaning lower prices for that stuff); and/or 2) will be turned off by goods’ tariff-inflated prices and choose instead to spend their finite dollars on other things.

The supply side of the inflation equation depends on real, economy-wide output, and here tariffs—especially broad ones—can have an effect by restricting that output (via higher input prices and economic activity pushed toward protected, less efficient industries). As the Cato Institute’s Norbert Michel and Jai Kedia explained back in March: “[T]ariffs result in higher prices and fewer goods available for sale in the United States. The higher and more widespread the tariffs, the bigger the reduction in goods and the larger the price increases.”

As you’ll recall, the Trump 1.0 tariffs were fairly targeted—steel, aluminum, washing machines, China imports (half), solar panels, etc.—and thus comprised a relatively small share of the goods measured in price indexes like the CPI. As a result (and because fiscal/monetary policy remained steady), those tariffs had an insignificant effect on the general price level and on inflation overall, even though numerous studies have since shown that U.S. consumers were paying higher prices for the tariffed goods at issue.

The bigger, global Trump 2.0 tariffs should have bigger effects, but the general principles still apply. Economist Bryan Cutsinger recently summarized the consensus view:

There seems to be broad agreement that higher tariffs lead to a one-time increase in the price level, not a sustained rise in the rate of price increases, that is, inflation. If it takes time for tariffs to pass through to consumer prices, inflation may temporarily pick up — a point Fed officials have acknowledged. But once the adjustment is complete, the inflation rate will come back down — that is, the increases will stop, even if prices themselves remain at a new, higher level.

Put another way, global tariffs will increase the price level but not its rate of change (aka “inflation”)—at least not in the longer term. Thus, most economists expect the CPI or PCE to tick up this year because of Trump’s tariffs, but only temporarily. (In general, the widely held view among various professional economists is that we’ll see a gradual, 1-ish percentage point increase in the CPI and PCE figures, peaking later this year and early next but mostly subsiding after 2026.) Those higher prices still mean pain for American consumers, of course, but the increase wouldn’t technically be “inflation” as economists understand and define it. And any CPI uplift we do see in the coming year or so will pale in comparison with the recent post-pandemic inflation we’ve lived through, because imported goods are still relatively small shares of Americans’ total spending.

So, from a theoretical perspective, discussions of tariffs emphasizing their effect on the overall CPI number and “inflation” are mostly missing the boat. It’s an issue, especially given all the uncertainty right now, but it’s not the issue—and few serious economists have said otherwise. (Far more of them, in fact, have said just the opposite.)

A Muted Response—So Far

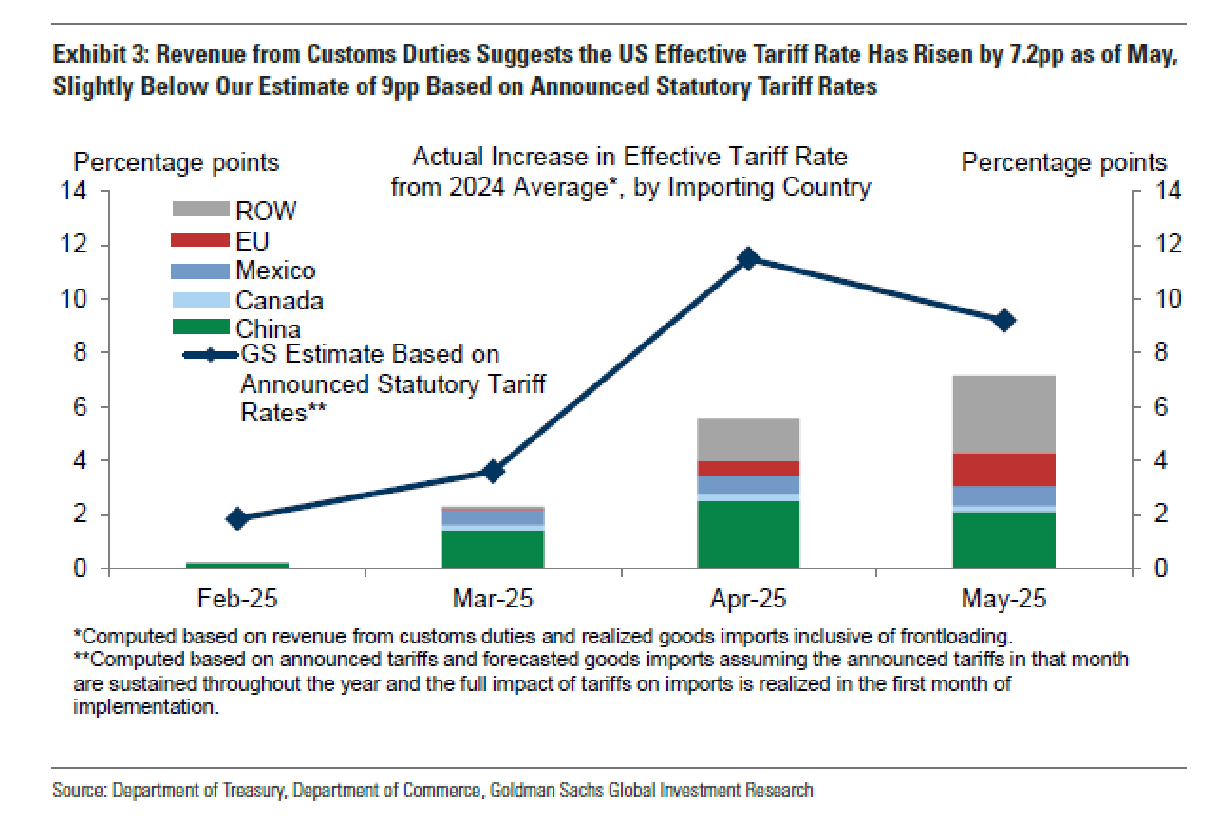

There are also several well-documented reasons for why even a temporary tariff-fueled increase in U.S. prices hasn’t materialized yet—and, in fact, might never show up fully in the CPI or other broad measures of inflation. For starters, Trump quickly rolled back some of his biggest tariffs (e.g., China and “Liberation Day”) and temporarily exempted many other products—semiconductors and consumer electronics, pharmaceuticals, many USMCA-compliant products, etc. As a result, a new report from Goldman Sachs (no link, sorry) shows, the average effective U.S. tariff rate is lower than some of the topline figures he has threatened (though it remains historically high)—and sat at about 9 percent through May of this year.

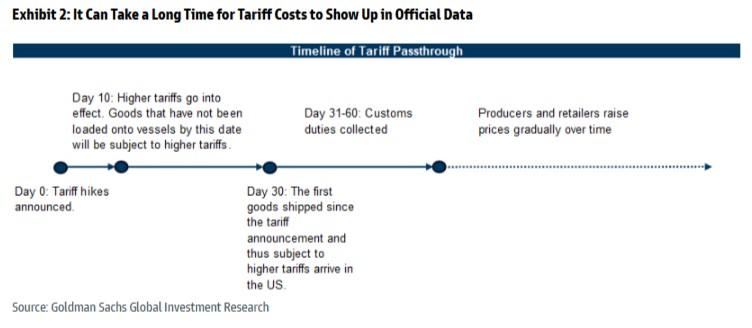

Then there’s the timing issue. Goldman notes that, from a purely mechanical perspective, it takes several weeks between the date of a tariff announcement and the tariff being paid by U.S. importers:

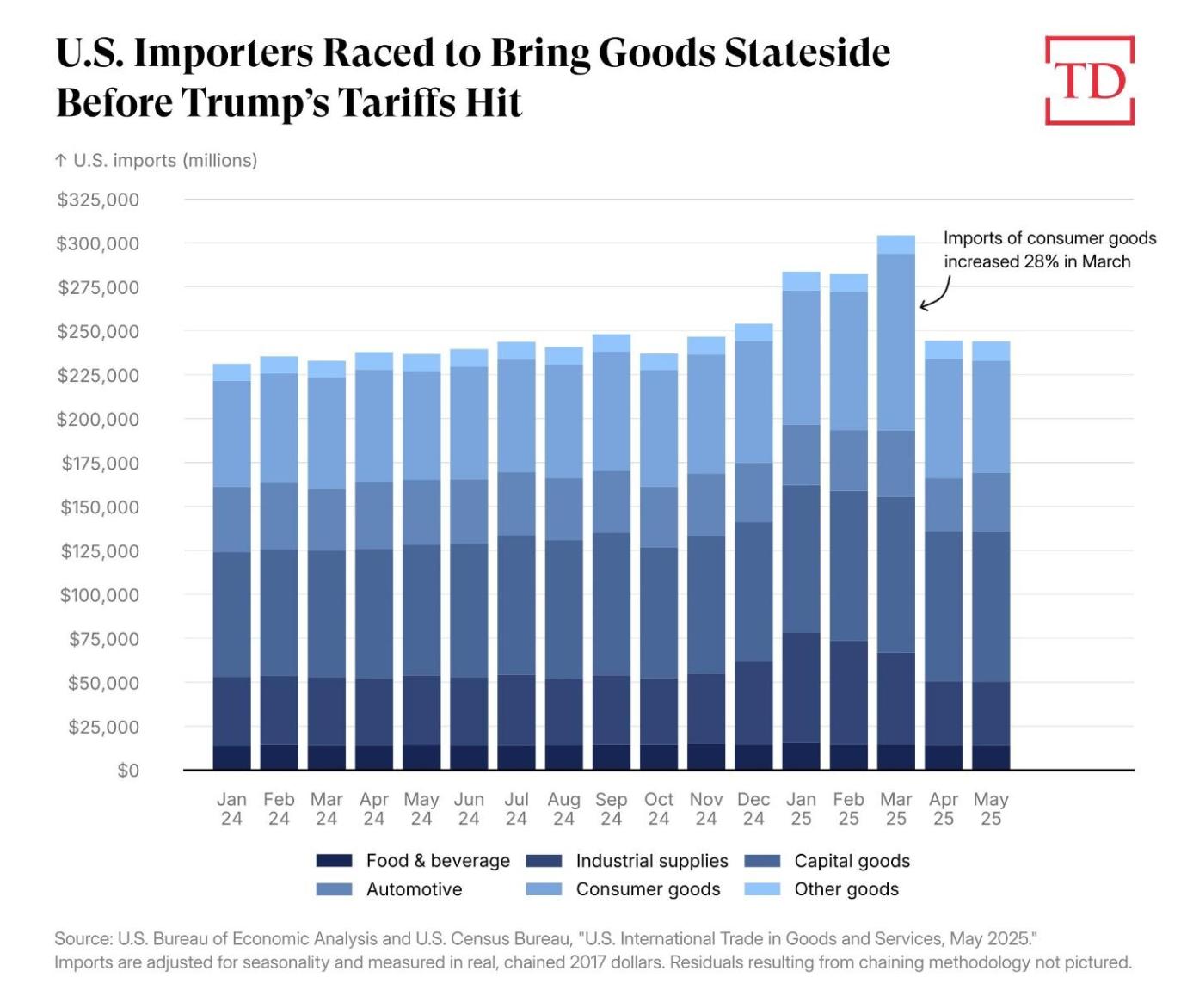

Meanwhile, American companies have worked hard to avoid paying the tariffs that are now in force. Most notable in this regard were their efforts to import goods before tariffs hit, thus resulting in a big spike in imports between November and April …

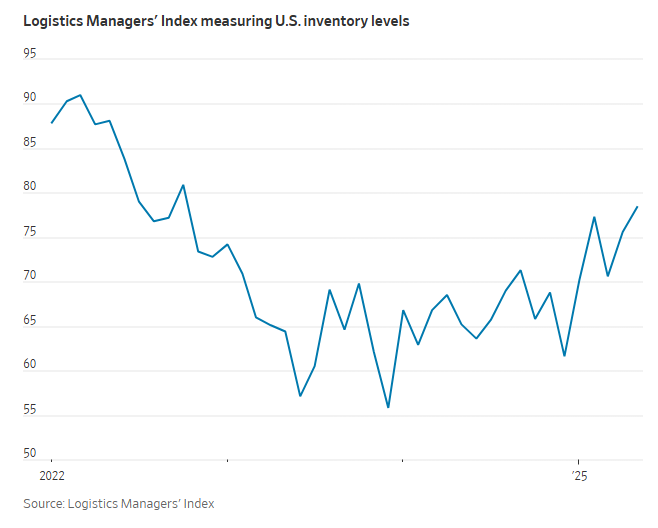

… and a resulting bulge in domestic inventories:

Stories abound of various companies and industries engaging in this simple and common tariff-avoidance scheme. The Wall Street Journal reported last month, for example, that U.S. pharmaceutical companies between January and April imported $36 billion worth of Irish-origin hormones that are used in popular obesity drugs—“more than double what was imported from Ireland for all of last year.” In one of my favorite examples, the CEO of Levi Strauss told investors in early April that, to avoid possible tariffs, it had “already imported most of the products it needs for spring and summer seasons,” giving them around six months of non-tariffed stock. Most importers (especially smaller ones) aren’t carrying that much inventory, but many had built up a substantial cushion before the biggest tariffs hit. Goldman notes other spikes for automotive, steel, and aluminum imports and suggests these efforts will allow U.S. companies to delay or spread out tariff costs for several more months, meaning less immediate pressure on their earnings and consumer prices.

Companies are also deploying other strategies to avoid taking a full tariff hit—at least in the short term. They are, for example, engaging in “tariff engineering”—reclassifying products into lower-tariff categories or ones with no tariffs at all. In one particularly ridiculous case, Delta Airlines is stripping out U.S.-made engines from its new Airbus jets in Europe and then installing them in grounded, U.S.-based planes—all to avoid Trump’s tariffs. Companies are also reconfiguring their supply chains to put final production in lower-tariff locations or to qualify under the USMCA (filing new paperwork along with it). They’re flooding into “bonded warehouses” and “foreign trade zones,” which allow importers to bring goods into the United States and pay duties only when they’re removed from the warehouse/zone and officially entered into U.S. commerce. All these efforts have a cost, of course, but it’s much lower than the tariffs themselves.

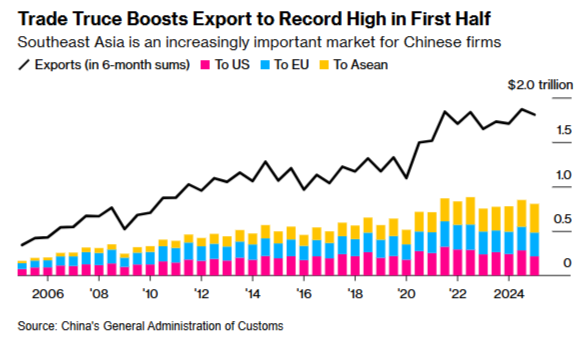

Then there’s the issue of foreign exporters eating the tariff costs by lowering their prices—Trump’s favorite excuse. As we’ve discussed, this is possible under the right circumstances but didn’t happen much during Trump 1.0, as American companies and consumers instead ate almost all of the tariffs’ costs. This time around, however, Goldman notes that there are some very early signs that foreign exporters, mainly Chinese, “have absorbed about 20% of the cost of tariffs”—an outcome that makes some sense given the sheer size of the tariffs, lingering inflation pain here, and widely reported deflationary problems in China. If these preliminary data hold, it’d be a shift from recent U.S. tariff experience but would still mean that Americans are paying about 80 percent of the tariffs’ cost—not exactly a huge Trump win. Other evidence, it should be noted, shows foreigners paying even less.

As tariffs really start to bite, the big questions will be whether foreign exporters keep eating some costs if it becomes clear tariffs are here to stay and how the remaining “80 percent” (or more) filters through the U.S. economy and into consumer prices—for both imports and domestic goods and services. And here, too, there are reasons to expect that the new costs won’t fully be evident in topline U.S. consumer price (inflation) data.

Most obviously, and as we discussed in September, American companies can eat the tariff costs themselves:

[W]hether end-consumers like you and me will see increased prices of tariffed goods depends on whether U.S. companies—importers, manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, etc.—pass on the higher prices they’ve paid. In some cases, they don’t. (Maybe, for example, they prefer to maintain market share and thus decide to just eat the tariffs’ cost and accept lower profits.) This can spare American consumers, but—just like corporate taxes—it doesn’t mean the tariffs are costless because the companies paying have less money for hiring, investment, and so on. And none of this changes the simple, basic, and obvious fact that someone in the United States paid more because of a protective tariff. Again, that’s the whole point.

Goldman estimates, in fact, that U.S. businesses have initially absorbed much of the new Trump tariff costs instead of passing them on to consumers, thus leading to a much more moderate impact on the inflation figures. Over time, however, they expect this balance to change and for consumers to bear half or more of the tariff costs (and related increases of U.S. goods’ prices), with price data eventually reflecting that burden. Anecdotes and alternative data, such as Federal Reserve surveys of U.S. businesses, show similar things.

American companies also are deploying clever ways to pass on their higher, tariff-related costs through things other than retail prices, thus potentially avoiding the ire of both inflation-weary American consumers and a certain U.S. president. This includes removing perks like free shipping or returns; leaning into resales of used or opened items that never faced tariffs; offering less favorable finance terms or fewer discounts; ceasing to sell lower-margin products; adding “tariff surcharges” to invoices; removing accessories and selling them separately; or using cheaper or downgraded parts in their products. Some of these things will show up in the CPI data, but some of them won’t. Regardless, they all still mean that American consumers are paying tariff costs—just less visible ones.

Still Reasons to Worry

Despite these mitigating factors, economists still expect a lot of Trump’s tariffs to eventually show up in the CPI and other broad measures of U.S. prices. Not only are the effective tariff rates rising, with more still to come, but inventories are dwindling and other tricks like bonded warehouses can only work for so long. Many companies, meanwhile, simply don’t have the profit margins to absorb all their new tariff costs—and, even if they did, their shareholders might not be too thrilled with that approach. (Foreign companies have the same problem.)

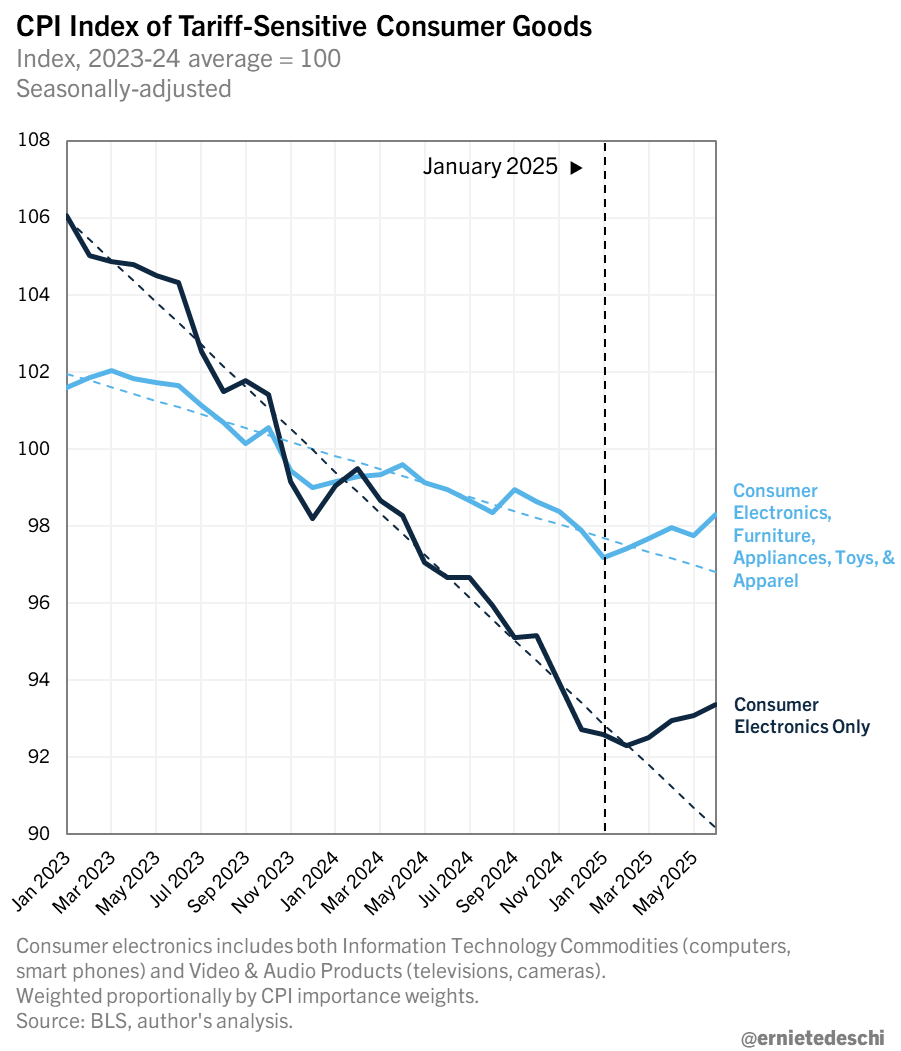

Finally, many U.S. companies have announced price increases, and more are on the way. I asked Claude AI to come up with a list of at least 100 public price hike announcements since February 1, 2025, and the bot completed the task in around 10 minutes—hooray, technology. Meanwhile, various data sources—including the CPI—show that Trump’s tariffs are starting to show up in national economic data. According to the Washington Post’s Heather Long, for example, the June CPI report showed the prices of import-sensitive categories—linens (+5.9 percent), cookware (+4 percent), audio equipment (+2.9 percent), appliances (+2.4 percent), sports equipment (+1.8 percent), toys (+1.4 percent), and more—experiencing abnormally large monthly gains. The Yale Budget Lab’s Ernie Tedeschi finds that goods are increasingly contributing to “excess” inflation this year and a clear break in the pre-Trump price trends for furniture, apparel, and electronics:

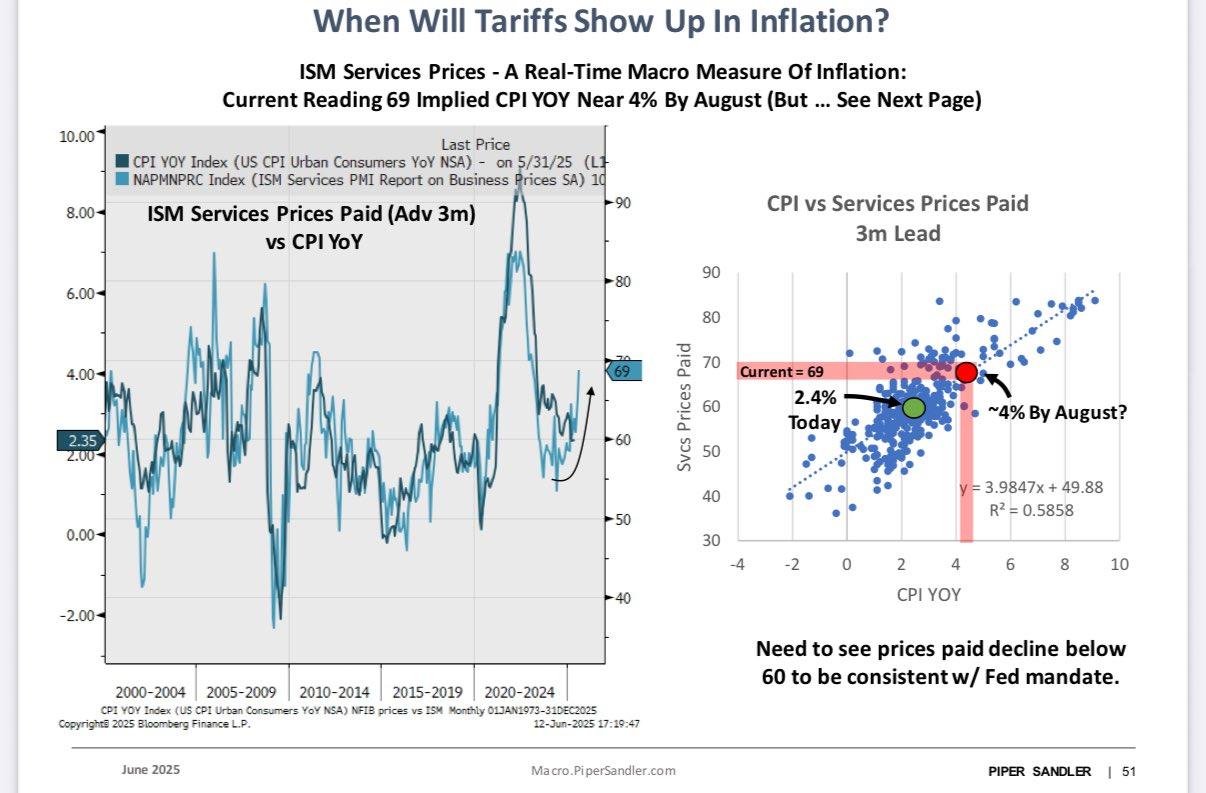

Beyond the CPI report, the Harvard Business School’s new Pricing Lab examines price data in real time and finds a clear upward trend in the prices of imported goods affected by tariffs and an almost identical trend for the same American-made goods. As tariffs rise and inventories disappear, we should see more of these price hikes in the months ahead. Economists also expect higher goods prices to eventually ripple into services like construction (via costlier materials), maintenance and repairs (via costlier parts), automotive insurance (via costlier cars and repairs), and health care (via costlier medical goods and drugs).

But, again, this doesn’t necessarily mean we’ll see persistent “inflation.”

At this point, the issue is less about whether tariffs cause higher prices but when the biggest hikes will hit. There’s no great, clear answer but—if recent trends hold—it should be sometime this fall.

We shall see. Regardless, dismissing the modest CPI and PCE data published so far—especially as some sort of hit on the “economists”—ignores not just theory but a boatload of reality too.

Summing It All Up

So, we shouldn’t expect Trump’s new tariffs to cause major “inflation” in the months ahead, but there are plenty of reasons to expect a significant, but temporary, spike in U.S. prices later this year. And some of the latter is already showing up in the data. Most people who actually do this stuff for a living (aka not TV pundits or viral posters) have been saying these exact things for more than a year now, so—as you can imagine—constantly repeating them in response to endless “inflation” inanity has become one of the more pointless and annoying parts of the job.

Probably the most annoying part, though, is that these technical details just aren’t something that matters to the vast majority of normal Americans. Sure, if you’re a Federal Reserve watcher, financial journalist, or investment banker, the precise trajectory and composition of our nationwide inflation indices is important. And the Fed’s current wait-and-see approach to monetary policy and tariffs certainly isn’t beyond debate, nor is the ultimate effect of Trump’s tariffs on real inflation in the United States. (FWIW, I know a lot of smart folks who think Fed Chairman Jay Powell is wrong to hold off on lowering interest rates because of tariff-related uncertainty; other smarties, meanwhile, see his position as defensible—especially with other signals pointing his way.)

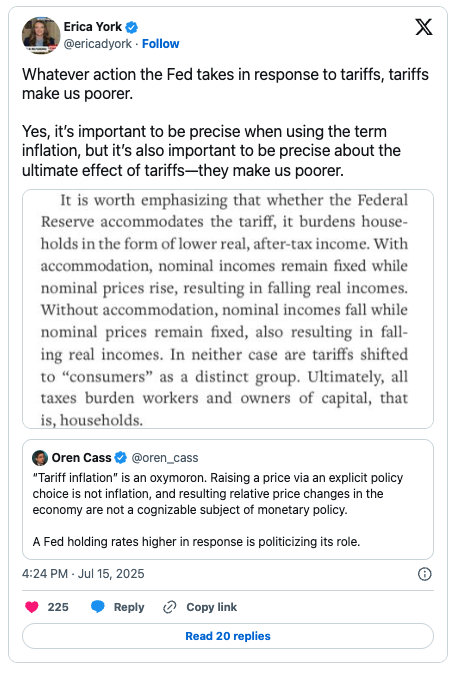

For most Americans, however, what matters isn’t the precise CPI reading or whether professional forecasters nailed their latest monthly predictions, but instead our actual living standards and—as our last election taught us—the price level, not its technical rate of change over a month or year. And here the tariff story isn’t in doubt: First, they will make many U.S. prices rise and, in fact, have already started doing so. And second, we will be poorer, regardless of what the Federal Reserve does.

Put simply, the primary problem with tariffs isn’t that they’re “inflationary”; it’s that they reduce the efficiency of our economy by distorting prices and undermining our capacity to produce real income. We pay (and work) more for less and end up materially worse off—regardless of what the CPI says.

Obsessing over “inflation” distracts from this reality, and that’s probably why the protectionists keep doing it.

Chart(s) of the Week

The Links

Upcoming Cato/Congress events on the Jones Act and tariff reform

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.