Dear Capitolisters,

With summer growing season in full swing and Father’s Day right around the corner, I’ve been tweeting about one of my new, very dad-ish hobbies—gardening. This has motivated several witty responders to ask why I—an outspoken fan of trade and specialization—am wasting my time growing my own food when there are better, more efficient producers only a few minutes (or clicks) away. Comparative advantage, they quip, would dictate that I leave the food-growing to the pros and spend my time doing more productive things like, umm, think-tanking (or is it tank-thinking?).

Anyway, this snark mostly misses the point. Gardening for me isn’t “work”; it’s an enjoyable leisure activity—one enabled by good ol’ free market capitalism and the ridiculous prosperity that it’s fomented here in America. As I tweeted the other day:

And this, I think, gets to an important, albeit nerdy point about our leisure time: While our hobbies and outside interests may differ, the same invisible—and awesome—economic forces let us pursue them.

Gardening Is Rewarding and Fun (for Me)…

Growing up and well into my 30s, I wasn’t much of a “yard guy” and certainly wasn’t a gardener. (My thumb was about as brown as they come.) Then in 2019 we moved to a new house with a relatively large swath of sunny ground that a former owner clearly used as a garden but had since fallen into weedy disrepair. Faced with the choice of trying to restore the garden or just grow grass, I decided—very much on a whim and with absolutely no idea what I was doing—to tackle the former, which took me almost a year to complete. (And I’m not gonna lie: I’m pretty proud of the final product, which I’ve nicknamed the SLAZ after the hilarious “People’s Garden” in Seattle.) When the pandemic hit, the garden became more of a focus because, well, I had little else to do.

Over the last year or so, however, gardening’s become a true joy—one that I’ll surely continue after the pandemic—for several reasons:

-

First, it’s relatively cheap, easy, and convenient. Sure, there are startup costs (containers, soil, seeds, etc) but you can get everything you need for a starter garden for around $100—at least some of which you’ll recoup once things are growing (especially if you’re growing and consuming things like peppers and herbs that can cost a small fortune at the grocery store). In terms of convenience, nothing beats just walking outside to snip a little basil (or whatever) when you’re making dinner. And there’s less waste because you’re just snipping what you need for the night, leaving other fresh snips for later.

-

Second, I derive a tremendous sense of accomplishment from planning, planting, nurturing, and harvesting something that I then get to consume regularly. Seeing a fully-grown plant bursting with ready-to-pick produce makes me feel like Tom Hanks in Castaway when he first made fire. (And I’m sure it’s just in my head, but the stuff from my garden just tastes better.)There are of course failures along the way, but this too is part of the process and makes the successes even more enjoyable.

-

Third, gardening has turned out to be a wonderful way for me to spend time with my daughter, away from the screens and other distractions that we all face. Gardens are constant work (in a good way), so there’s always something to do out there. Not only do we get to spend some screenless QT together, but she loves seeing her plants grow and might even learn a little about horticulture, attention to detail, and commitment. It’s prime dad stuff. (I’m not crying, you’re crying.)

-

Finally, gardening’s a great way for me to detach from the world and decompress after a long day—especially important for a guy like me who works from home. I can turn on some tunes, get dirty, and unplug for a bit – something we all need (especially in these days of 24-7 media).

Maybe (okay, surely) gardening isn’t for everyone, but it’s become a real joy for me and my family and a great, rewarding way to spend some of my free time.

… And the Free Market Enables It

More importantly for today’s purposes, however, is that several wonders of modern free market capitalism let me grow food for fun, instead of just to stay alive. You might snicker at that last part, but you really shouldn’t: Wikipedia notes, for example, that as of 2015 about 2 billion people (more than 25 percent of the world’s population) in 500 million households were engaged in subsistence farming. And in the United States, about 72 percent of the population worked in agriculture in 1820 (the first year data were available), as compared to less than 2 percent today. Similar trends hold for other developed nations, such as those in Europe.

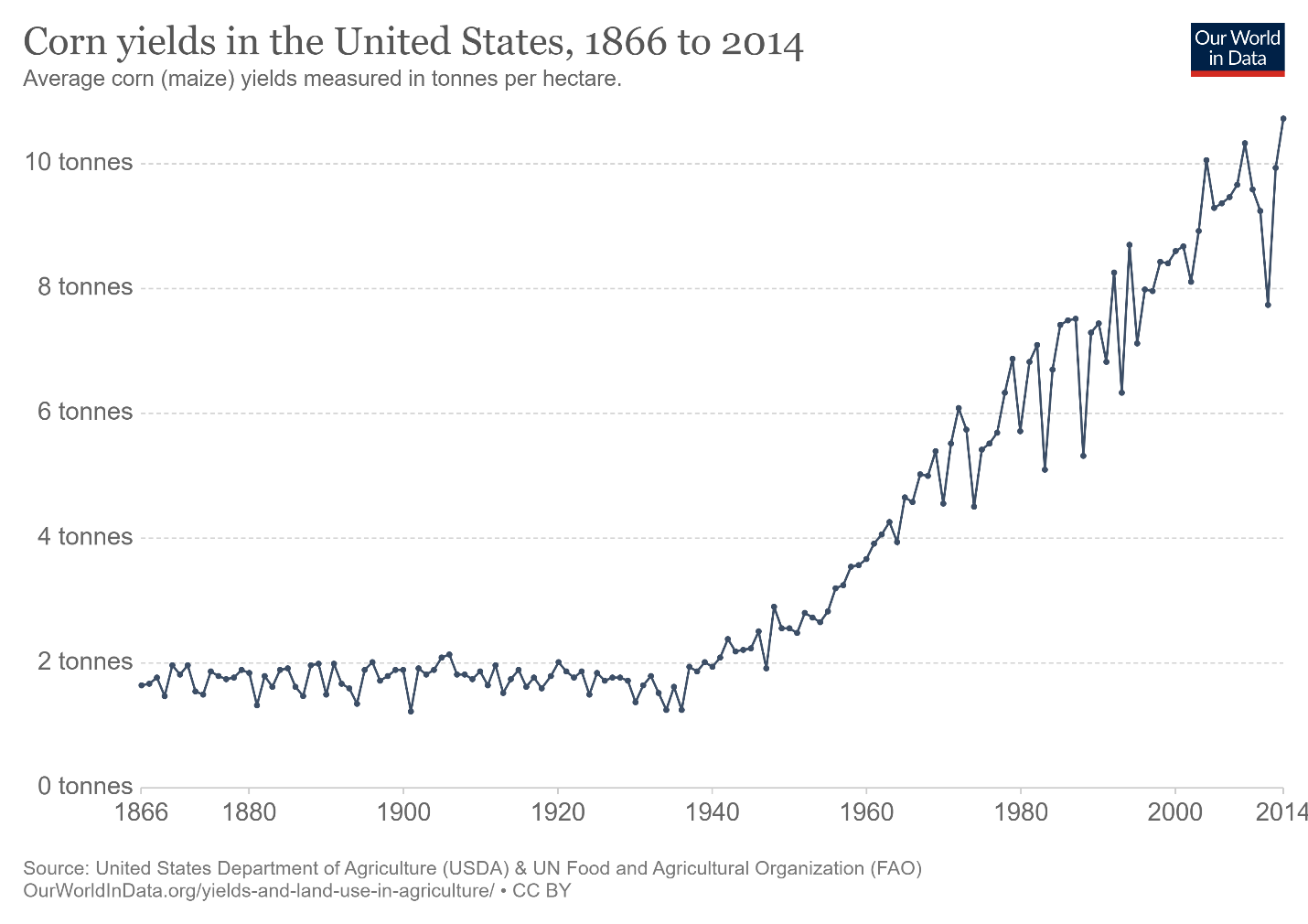

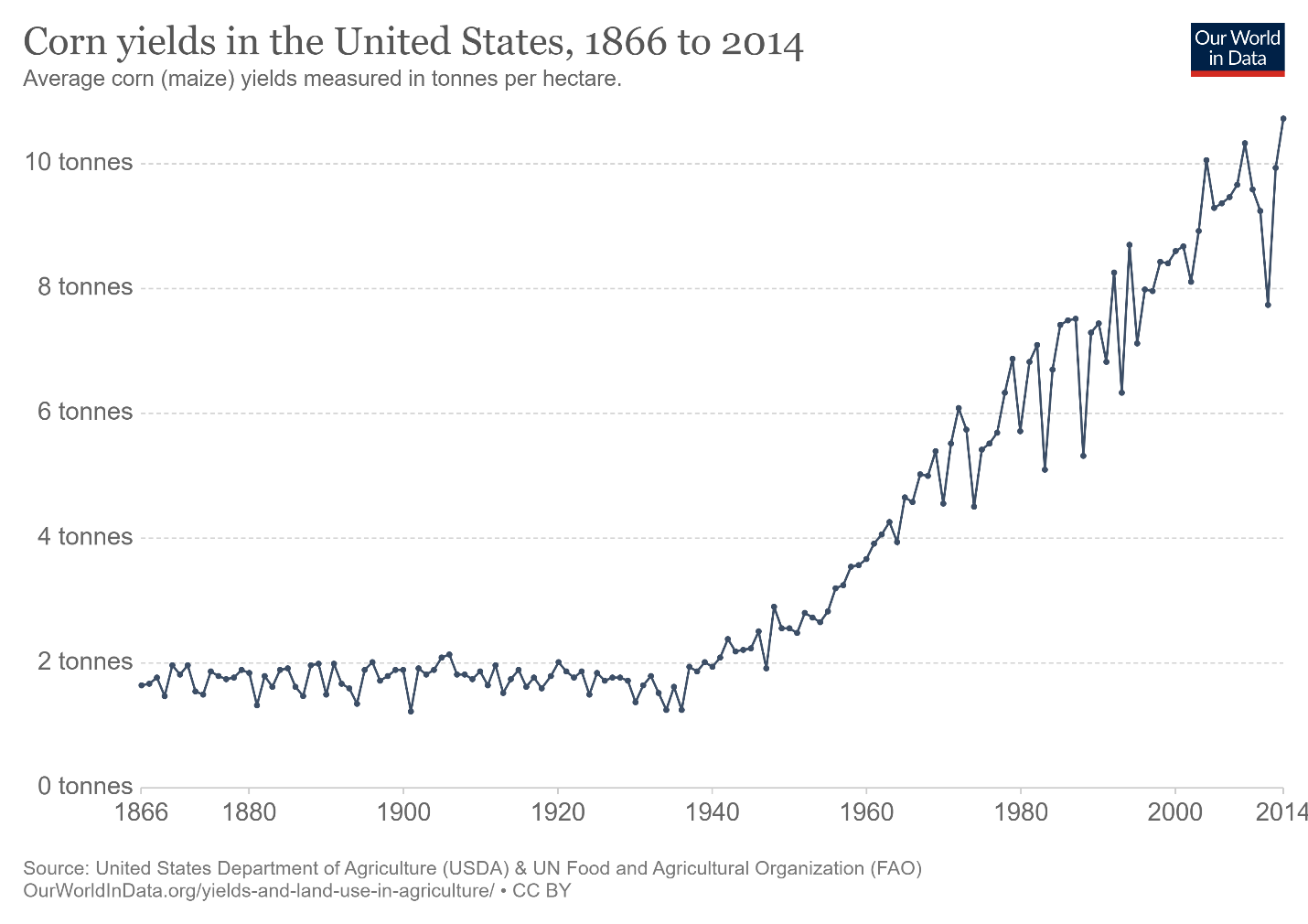

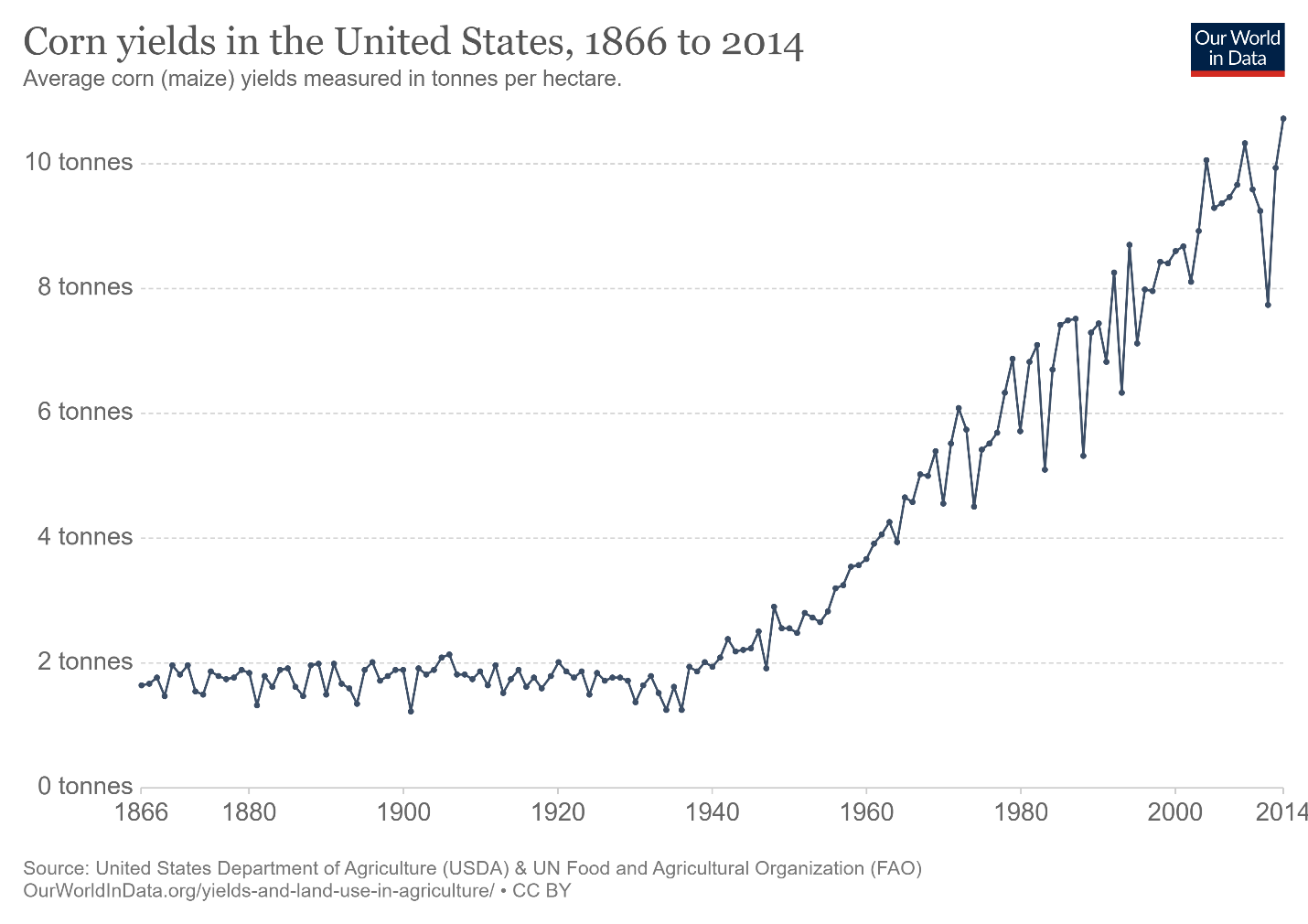

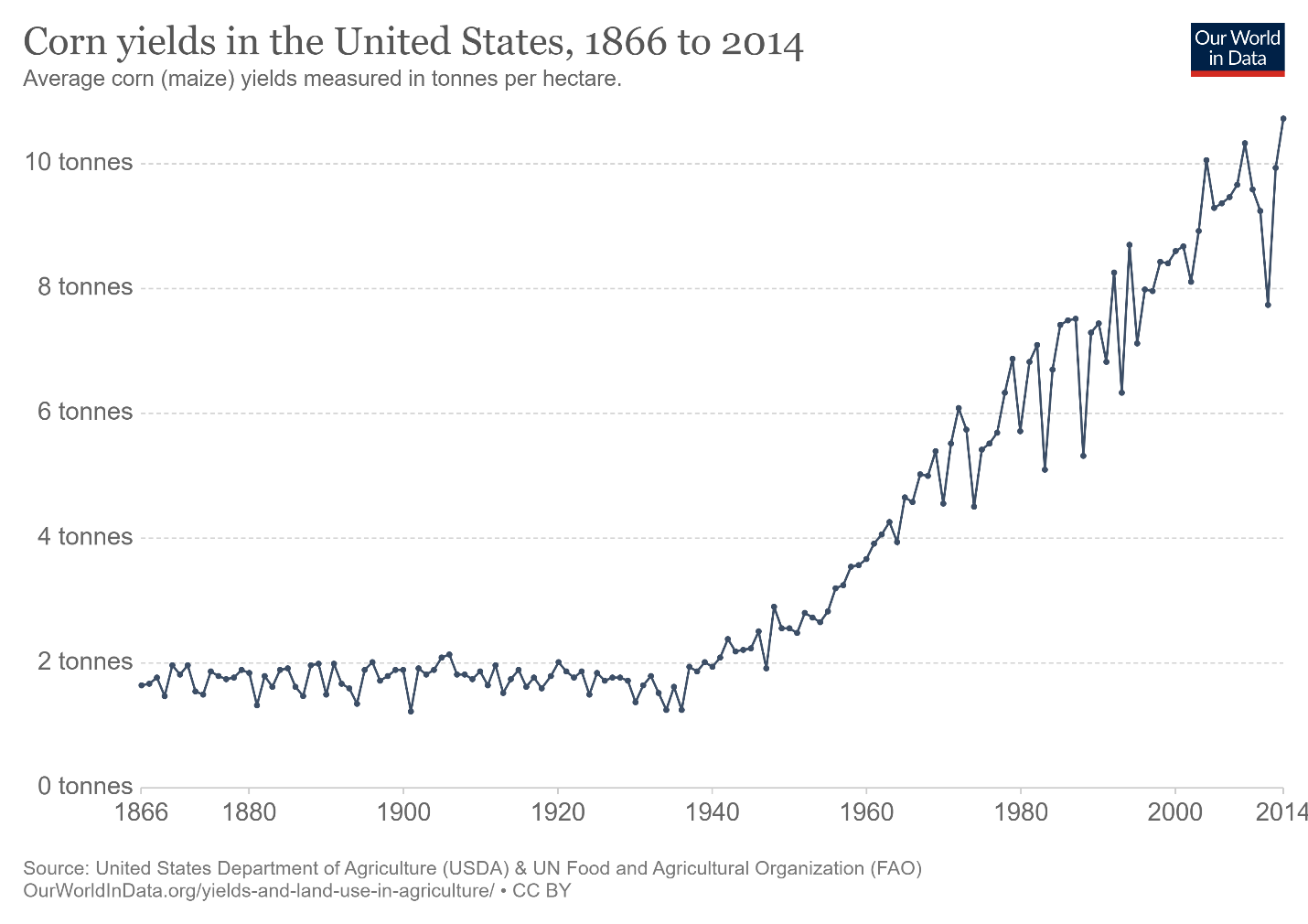

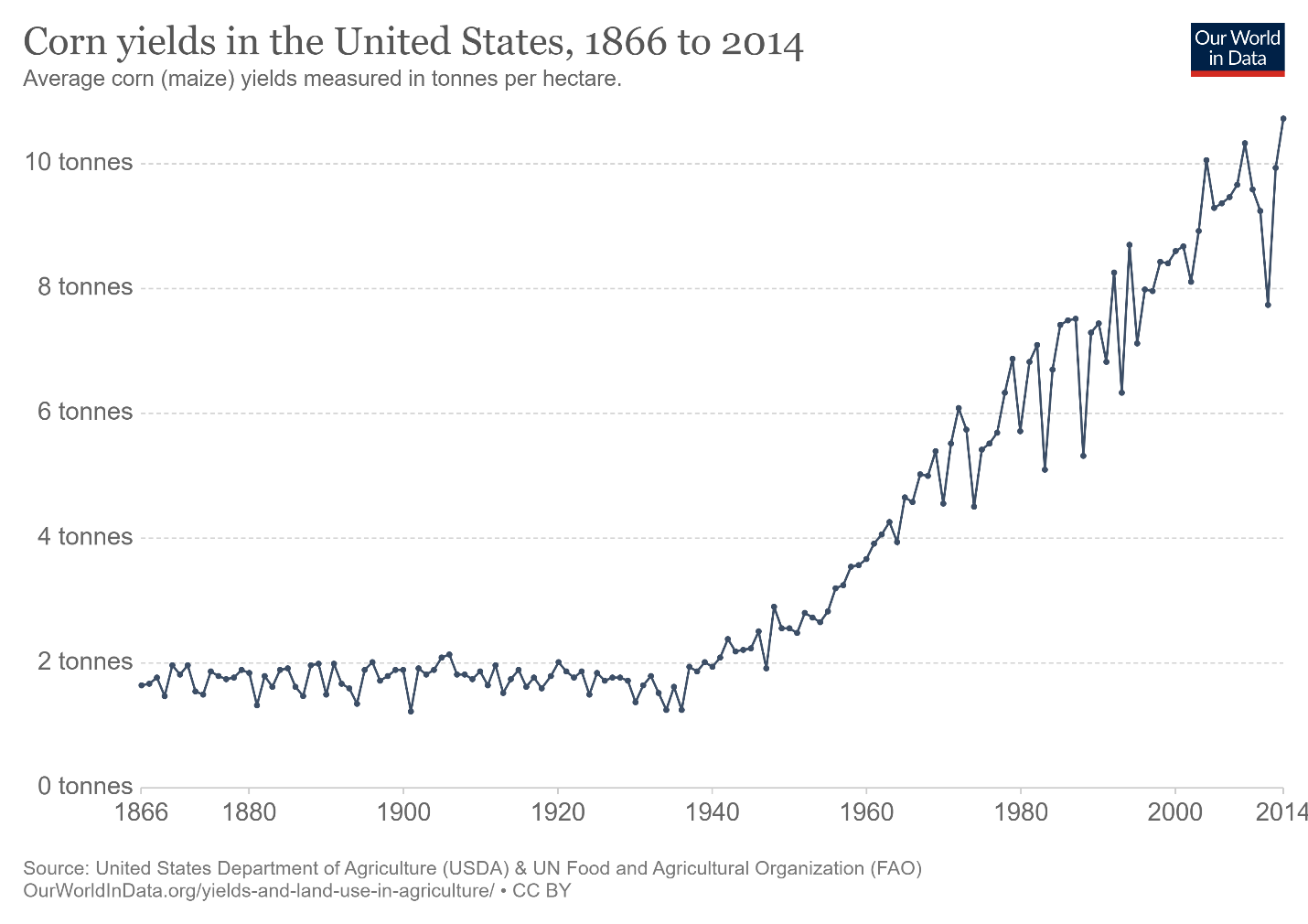

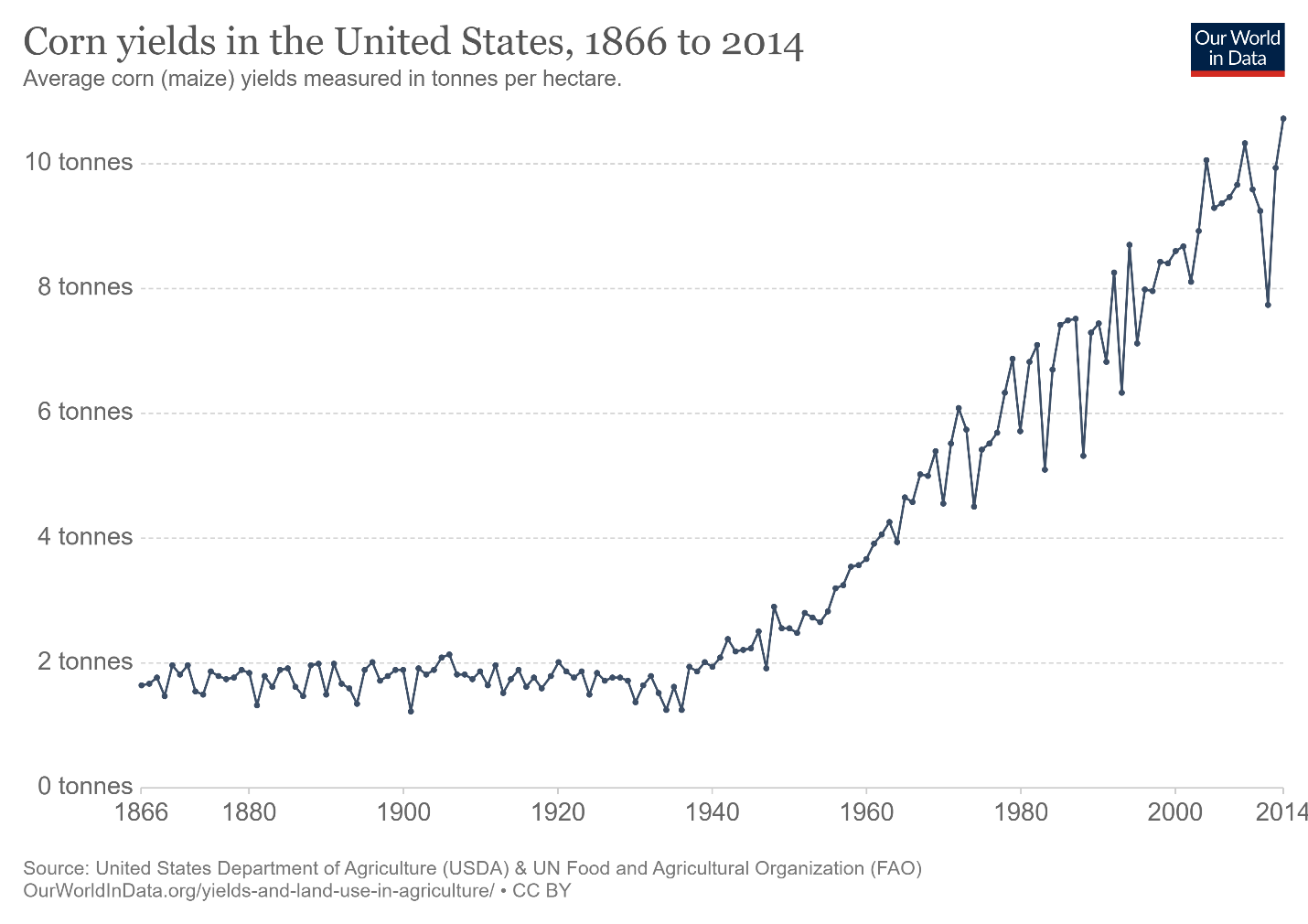

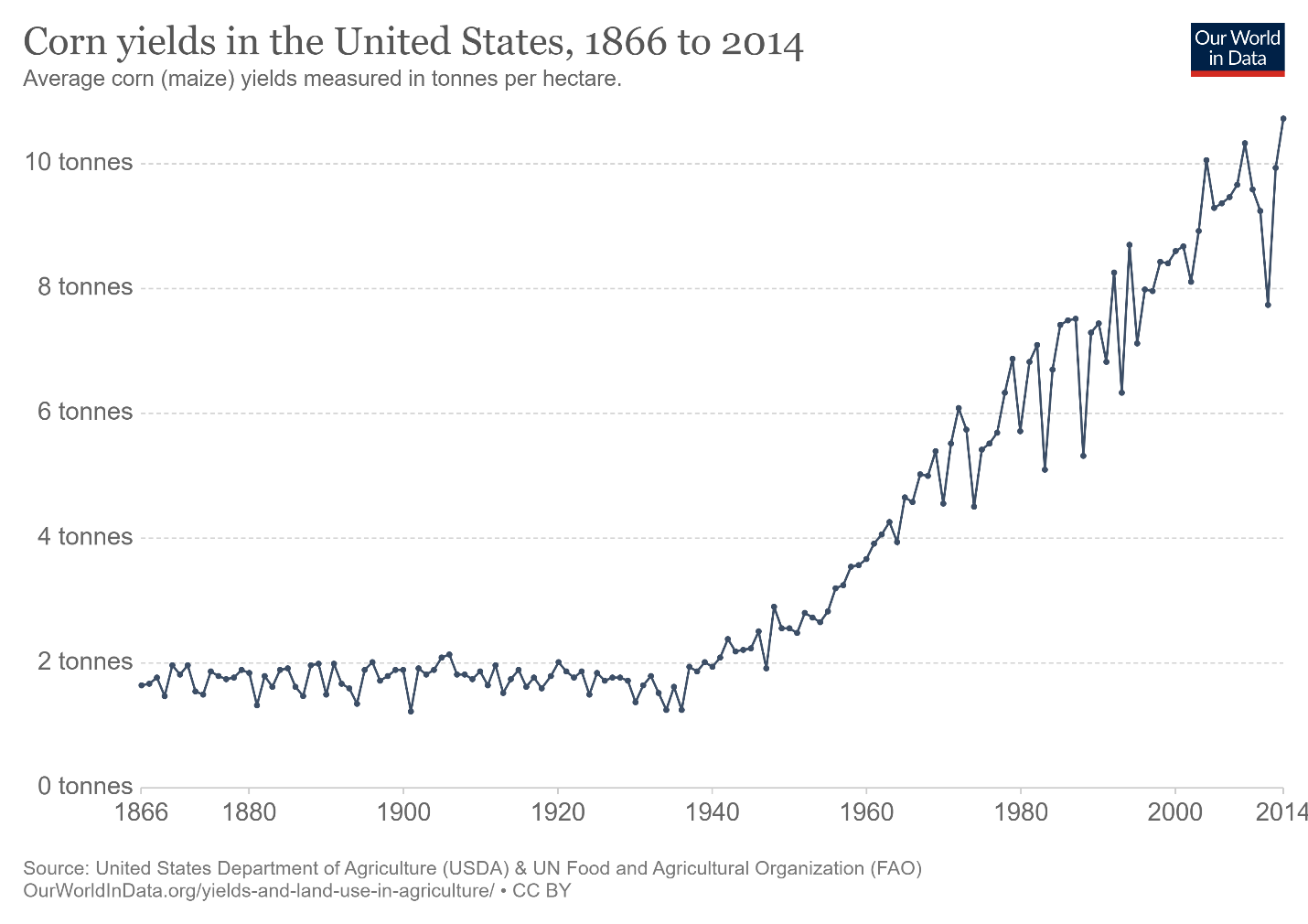

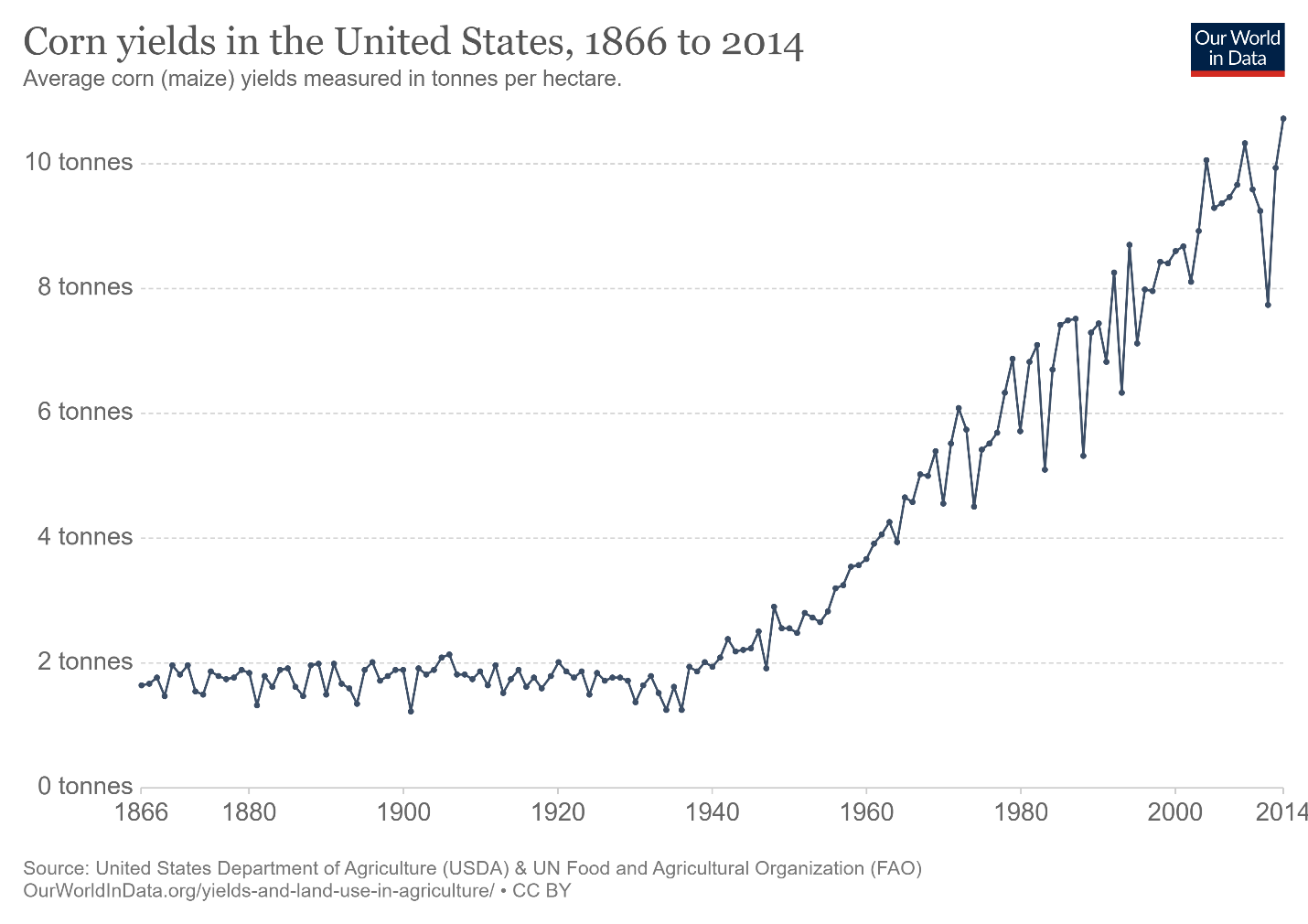

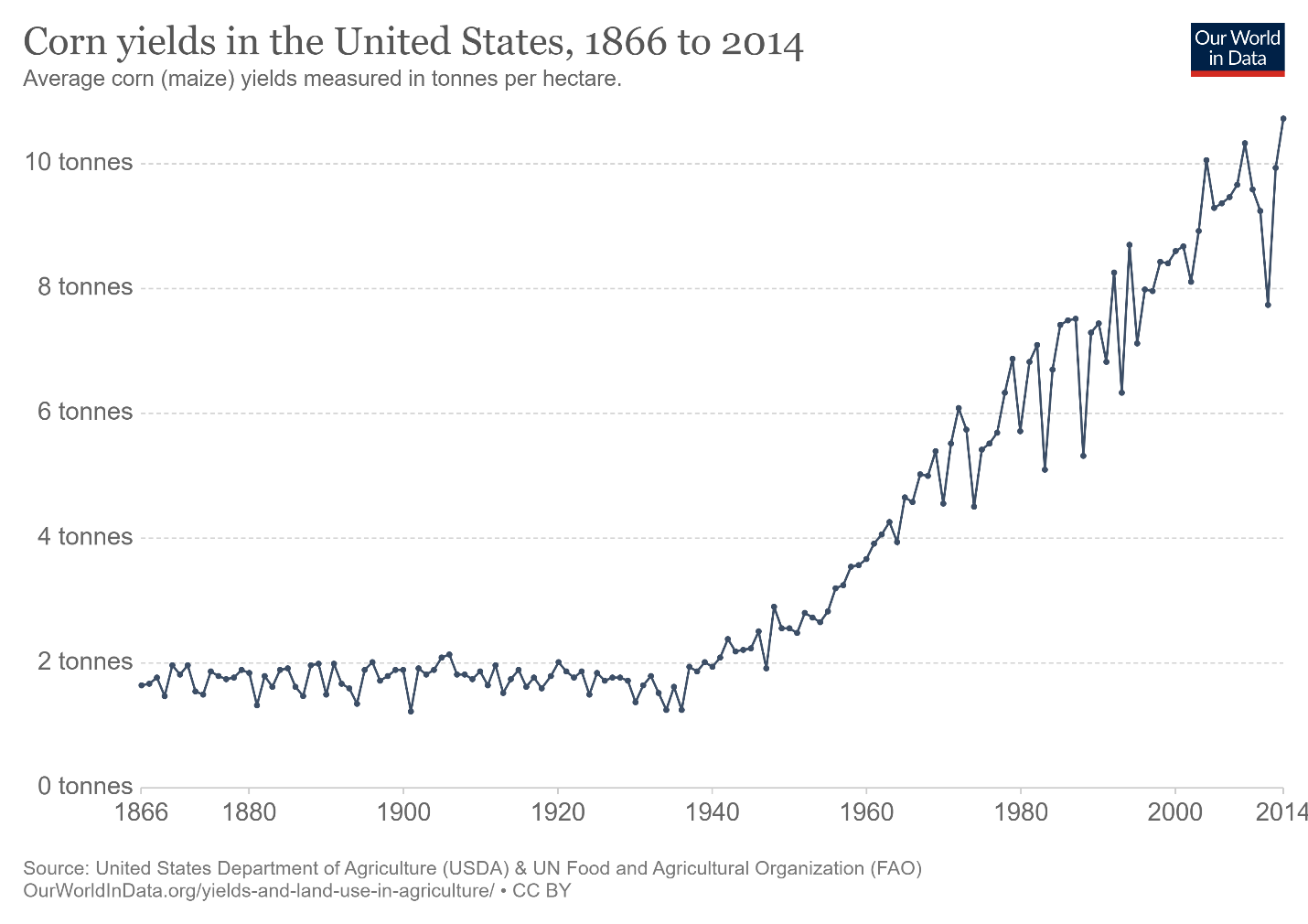

Radical improvements in agricultural productivity (e.g., crop yields) drove much of these declines, lowering the inflation-adjusted prices of most agricultural commodities and the number of jobs needed to produce it.

The food price trends above are global, but they also apply to the United States alone. For example, AEI’s Mark Perry found last year—as part of his annual check-in on Thanksgiving dinner costs—that “[c]ompared to 1986, the inflation-adjusted cost of a turkey dinner this year is 31% cheaper.” More stuffing for me, please.

At the same time, most of the humans who used to farm have been freed up to pursue other vocations that they deem to be more enjoyable and more lucrative. Thus enters the division of labor, specialization, and trade, which – as Adam Smith taught us centuries ago – combine to give me both the time and money to engage in a hobby that used to be a terrifying, backbreaking necessity occupying almost every waking hour of our days.

A viral YouTube video from a few years ago provides a great example of the poverty that this (once-mandatory) self-sufficiency engendered. There, Andy George spent six months and $1,500 to make a sandwich from (almost) scratch. Using this episode as a springboard for one of the many lessons in his great new book, Economics in One Virus, my Cato colleague Ryan Bourne explained how this shows the benefits of specialization:

There’s an important lesson from this story about the desirability of self-sufficiency. It turns out to be extremely inefficient to try to produce everything by yourself. George remarked he could have bought an expensive artisan sandwich for just $15 nearby, but his efforts had cost 100 times that, at a massive opportunity cost of lost time. As we’ve mentioned, economists describe opportunity cost as the value of the best use that we forgo when we use any resource—including the value of the best alternative use of the time that George had put in over six months.

It’s for this reason that most of us don’t try to be self-sufficient in producing what we consume. We might grow some of our own herbs or produce some personal arts and crafts. But there’s no way any one person would ordinarily go about producing his daily sandwich from scratch, let alone building himself a computer or a television. Mercifully, a market economy where we can trade freely allows us instead to specialize in activities that we are relatively efficient at, earn money from this activity, and then purchase things that others produce relatively more efficiently than us….

Markets where trade can occur as freely as possible help create opportunities for richer and deeper specialization. That allows us to produce more at lower cost, making us wealthier and ultimately granting us more resources to then consume other products.

Thus, like Ryan, my specializing in wonkery and purchase of basic necessities with the proceeds therefrom—necessities produced cheaply and efficiently by others who have specialized in that production—gives me the luxury of buying food cheaply, dabbling in additional food production for fun, and having the extra cash to buy the relevant supplies to do it (more on this is a sec). And I’m certainly not alone: according to the USDA, for example, Americans spent a historically low share of their disposable personal income on food in 2019—a trend driven by both lower food prices and higher incomes (which very few of us earned from farming):

Just as importantly, technology and specialization give me—all of us—more time to do such dabbling, because rising labor productivity not only increases incomes but also decreases working hours. Indeed, as shown in the following chart, average annual working hours have declined dramatically since the end of the 19th century (dropping by a whopping 1339 hours per year—from 3096 to 1757—in the United States):

As economist Tim Worstall recently explained, moreover, other advances in technology mean that we don’t have to spend this nonworking time on things like housework:

One author estimates that it took 60 hours a week of physical labor to keep a 1930 household working. Today, it takes perhaps 15 hours. Those numbers are not exact, but when you consider the washing machine, the gas oven, the vacuum cleaner, prepared food, and steam irons, the amount of household work eliminated is immense. One of Hans Rosling’s TED talks recounts how the washing machine brought him books. According to the Swedish physician, once the washing machine liberated his mother from laundry, she had more time to read to him. The South Korean economist Ha Joon Chang claims that the washing machine—by which he really means all domestic labor-saving technologies—changed the world more than the internet.

The decline in housework hours was a particularly big deal for women, who typically handle more of it and—freed from those tasks—often chose to use their newfound time in the formal workforce. Combine both declining labor hours and housework hours, Worstall notes, and you get households with more leisure time overall. He cites a report from a the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, which finds that, between 1965 and 2003, “leisure for men increased by 6-8 hours per week (driven by a decline in market work hours) and for women by 4-8 hours per week (driven by a decline in home production work hours).” Today, Americans tend to have about five hours per day for leisure activities (men more than women)—a number that’s been remarkably steady for prime-age adults since the Boston Fed study ended:

Finally, the market supports my little hobby with all sorts of goods and services that I didn’t even know I needed (until I did). I bought pre-drilled but unassembled cedar boxes, as well as several gardening tools, on Amazon. A local landscape supplier sold and delivered giant piles of dirt/fertilizer (“50/50 mix”) for the beds and gravel to surround them. I bought seeds from a nearby garden store for peas, carrots, cucumbers, and squash, but also found dozens of other suppliers—at the farmers’ market, Big Box home stores like Home Depot, or even Amazon—who sell incredibly cheap “starter plants” to speed up the growing process and avoid the hassle (and stress!) of waiting for sprouts. (This is particularly great for lettuce, peppers, and okra.) And then, of course, there are all the books and videos and Twitter accounts—all dedicated to helping me pursue my manifestly frivolous hobby. It’s pretty amazing, really.

None of these goods or services—or the thousands of their sellers (hundreds in my city alone)—resulted from a top-down, central plan drafted by a board of bureaucrats or politicians looking to subsidize home gardening. They emerged spontaneously to meet my desire (technically, the desires of many before me) to get my hands dirty in my yard. And then competition for both my dollars and my eyeballs, as well as good ol’ globalization, drove these suppliers to constantly improve the value (quality, price, delivery, etc.) of their wares.

The proliferation of low-cost “recreation goods” not only makes my hobby easier, but—as noted in a recent NBER working paper—may also help to increase my leisure time overall (emphasis mine):

The real price of recreation goods and services has fallen dramatically over the last century. At the same time, hours per worker have also been on a steady decline. As recreation goods make leisure time more enjoyable, we investigate if the fall in their price has contributed to the decline in work hours. Using aggregate data from OECD countries, as well as disaggregated data from the United States, we provide evidence that the two are strongly related. … We estimate the model and find that a large part of the decline in hours worked can be explained by the declining price of leisure. In contrast, we find mixed evidence that higher wages contributed to the decline in hours worked over the last several decades.

In other words, a big reason why people are working less today, and thus spending more time doing “leisure activities” like gardening, is because technology, specialization and trade have made participating in those activities much cheaper (thus requiring less work to afford them). As Bourne notes in a separate column, that doesn’t mean that we’re moving to Keynes’ 15-hour workweek anytime soon, but it does mean that many of us will tweak our work-leisure balance a little more towards the latter.

Summing It All Up

So the free market gives me the money and free time to pursue agriculture as a hobby and supplement my cheap and healthy groceries with home-grown herbs and produce. And dozens upon dozens of total strangers—some of whom live thousands of miles away—are just itching to help me do it. Maybe gardening’s not for you—my sales pitch and tips notwithstanding—but that’s the beauty of the situation: by freeing us from the brutal poverty of autarky and antiquity, the market lets us pursue things we actually enjoy—for work or play. And nobody planned a thing.

Chart(s) of the Week

The Atlanta Fed finds wage pressures for the first quarter of 2021 were limited to low-wage service occupations:

Labor force composition is changing the same way in the developed world (source)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.