Dear Capitolisters,

As you (hopefully) read in Monday’s Morning Dispatch, President Joe Biden late last week issued an extensive executive order “encouraging more than 12 federal agencies to carry out a total of 72 different initiatives aimed at increasing competition and fighting what the White House described as a ‘trend of corporate consolidation.’” As your faithful Morning Dispatchers note, the order itself is essentially toothless because it leaves implementation to the targeted agencies through rulemaking and enforcement. But it still should be taken seriously as a strong indicator of the direction the executive branch (and congressional Democrats) wants to move both U.S. competition policy and government power in the next few years—a direction seemingly shared by a lot of Republicans and one that, I think, is troubling.

Competition Policy as a Political Tool

The Biden EO is far too broad to dissect in a single newsletter (even I have my limits). In general, I agree with the TMD analysis and others that see the EO’s specific provisions asa mixed bag of good (occupational licensing, over-the-counter hearing aids, etc.), bad (airline WiFi fees, likely farm subsidies, net neutrality, internet marketplaces, retroactive merger review, etc.), debatable (noncompete agreements, drug reimportation, etc.), and unclear or already-happening (shipping fees, hospital prices, etc.). How these specific guidelines are interpreted and implemented will make each of these directives—and what analysts think of them—clearer, but it’s going to take some time.

What’s already clear, however, is that Biden’s EO and related statements are less about offering a coherent and objective economic framework for regulating U.S. corporations and more about proactively using government power for subjective and political ends. Just to be clear: By “political” here I don’t necessarily mean winning elections but instead about using government force against disfavored corporations to achieve essentially any economic or social outcome that favored interest groups—consumers, workers, farmers, or even other large companies—desire. Thus, the EO contains “pro-consumer” provisions, “pro-labor” (including pro-union) provisions, and even “pro-business” provisions, the tilt of each depending on the “Big Corporations” and social/political objectives at issue. At the same time, it ignores startlingly similar phenomena regarding other industries and interest groups that have, for whatever reason, less political salience (in the White House’s view).

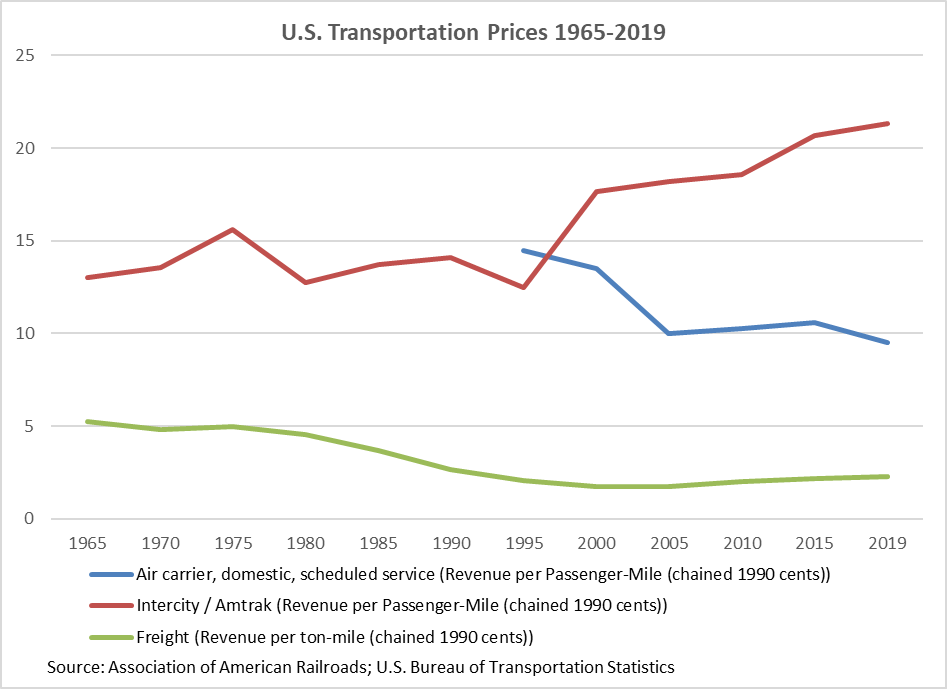

As I noted in a blog post last week, perhaps the most absurd example of this issue is the EO’s plans for regulating freight rail and ocean shipping markets, which are today grappling with the same pandemic-induced demand-supply imbalances that many domestic industries and global supply chains are facing. There, the White House has directed the relevant agencies to go after practices that supposedly harm certain transportation users, while ignoring the U.S. laws (e.g., the Jones Act and Buy Americanrules for rail) and organized labor practices (e.g., contracts prohibiting port automation) shown to do that very thing. They also ignore that the ocean shipping problems are hardly new and mostly pandemic-related, and that inflation-adjusted freight rail prices declined following deregulation of the industry in the 1980s and have been flat since the mid-1990s. This latter trend is particularly apt when you compare prices for freight rail and passenger airlines (also targeted by the Biden order) to ever-increasing Amtrak prices:

The only coherent thread throughout the EO is that the Biden administration wants U.S. competition policy (i.e., the federal government) to actively work to alter the balance of power between certain companies and certain domestic interest groups.The criteria for adjusting those scales seems to depend on who’s involved and what the White House thinks is right. As we’ve discussed, this is a radical shift away from the longstanding, more objective “consumer welfare” standard that has governed U.S. antitrust and competition policy back to the progressive, and far more subjective and political, “trustbusting” approach popular a century ago. It’s a move from economic “efficiency” to “preserving democracy,” as the Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip puts it.

And it’s not just economics correspondents like Ip or irked free marketers like the Wall Street Journal editorial board noting the change. In yesterday’s New York Times, for example, history professor Nelson Lichenstein (a clear fan of the move) cheered Biden for restoring the progressive “tradition [that] worries less about technocratic questions such as whether concentrations of corporate power will lead to lower consumer prices and more about broader social and political concerns about the destructive effects that big business can have on our nation.”

As economist Don Boudreaux notes, achieving both “social and political” and economic (efficiency) objectives will be exceedingly difficult: There is often a tension between interests of consumers (who want prices minimized and choices maximized) and those of the politically favored businesses and workers that serve them (who tend to want the opposite). Thus, for example, unions and import-sensitive companies seek government protection from foreign competition while consuming companies, retailers, and individual consumers (when they’re paying attention and ) want freer trade. And if economic efficiency and the consumer welfare standard guided government policy in transportation, we’d see the Biden administration target for reform the U.S. cabotage laws (in domestic air travel too), Buy American rules, and labor union practices that clearly disfavor American transportation consumers. Instead, the EO ignores the first two and openly roots for new congressional legislation—the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act—boosting union power even more.

Chalk one up for “social and political” (sorry, consumers!).

The Bipartisan Embrace of State Power

As Ip notes, the Biden administration’s embrace of state power is unsurprising given the “Brandeis School” progressives appointed to run the competition policy show and longstanding lefty complaints about markets and social issues like inequality, but it’s not merely these progressives motivating the “backlash against the pro-market principles that have governed economic policy for decades.” Conservative populists today, for example, blame free trade, “open borders,” and “giant multinationals” for destroying manufacturing, sole-breadwinner families, and Midwestern communities, while threatening to tax or regulate Big Tech and “woke corporations” has become a litmus test for any populist seeking to win a Republican primary. Large parts of both the left and right have embraced state power to rebalance the relationship between corporations and members of “their team.”

Embedded in this embrace is the increasingly bipartisan idea that certain corporations present a greater threat to Americans’ life and liberty than the state, so the latter—regardless of the risks—must be used as a hammer against the former. As writer Matt Taibbi recently claimed to the New York Times Jane Coaston, for example, “I am deeply worried about Silicon Valley — the confluence of companies like Amazon, Facebook, Google, Twitter. These companies are more powerful than nations are at this point.” Google around and you’ll find the same things being said on the right (and by others on the left) about not only Big Tech, but also Wall Street and various multinationals. Indeed, just as Biden’s EO was coming out, former President Trump was suing Facebook, Twitter, and Google, claiming that they are “government actors” and thus prohibited by the First Amendment from “censoring” him and any other user.

All of this is not only misguided but dangerous. For starters, as I wrote at length a couple weeks ago, politicized competition policy has the potential to expand the abuse of a legal regime that has already seen its fair share of problems under a far less discretionary (more economic) standard. As Ip warns at the end of his piece, “For all its flaws, antitrust governed by the consumer welfare standard is less at risk of politicization than beliefs about what’s good or bad for democracy.” So get ready for more of that.

More fundamentally, however, the populist view of corporate bigness ignores the true and unique power of the state. When Taibbi asks Coaston why she isn’t concerned about social media giants refusing to distribute her writing, she rightly replies (emphasis mine):

Yeah, but they could say that to me anyway today. I mean, the Times could do that right now if they wanted to. I recognize that these companies have an immense amount of power. But we tend to treat power as...a pie, that we’re like, well, if Silicon Valley has this much power, that must mean that state governments or the government writ large has less power because Twitter has more power, when I don’t think that’s how it works. All of these entities have a lot of power, but state government has the power of state violence.

On Twitter, Kevin Glass of the National Taxpayers Union provides a recent and concrete example in Belarus of just how unique this power really is:

There’s no need to leave the United States or even to resort to the history books to see such power—and its potential for abuse—firsthand. For starters, our criminal justice system is riddled with horrific and often-unreported examples of innocent individuals harmed or imprisoned on the flimsiest of evidence, often to boost the career prospects of the ambitious state officials involved. (An old friend of mine helped right one of these wrongs in Texas, getting his client’s obviously wrongful conviction overturned after he spent six years on death row. And said client is one of the lucky ones.)

But it’s not just poor, unknown individuals at risk of such deprivations. Just look at what California is doing to one of the world’s most famous people—pop star Britney Spears—right out in the open:

[F]or 13 years, courts in California have rewarded Spears’s father Jamie, a failed businessman who struggled with alcoholism, once filed for bankruptcy and who, according to the documentary Framing Britney Spears, was often absent from his daughter’s childhood. They have enabled arguably the most egregious villain of them all. In 2008, when his daughter suffered an apparent mental health crisis, Jamie asked a court to make him her conservator — that is, legal guardian. He has mostly kept the power since. He has decided which friends she sees, what medical treatment she receives and what happens to her fortune, estimated at $60m.

…They had made her work seven days a week, taken her credit cards and given her no privacy when undressing. “In California the only similar thing to this is called sex-trafficking,” she said. They would not let her have an intrauterine device removed, because they didn’t want her to have more kids. But they did allow a doctor to prescribe her lithium “out of nowhere”.

Detailed reports of this travesty (and U.S. “guardianship” law more broadly) continue to trickle out, yet the state just denied Spears’ November 2020 request that her father lose control of her finances. (Bravo to George Mason’s Tyler Cowen and others for helping to publicize this miserable situation; maybe it’ll help the odds of her new request for freedom, though that result would also underscore these laws’ bigger problems.)

Let’s examine economic regulation, starting with eminent domain and the case of Kelo v. City of New London, in which the Supreme Court allowed Connecticut town to take Susette Kelo’s house for the “public use” of getting one of the world’s richest companies, Pfizer, to locate there. (Pfizer never did, and the land is still vacant today.) Though some states implemented reforms in Kelo’s wake, eminent domain abuse remains common.

Other Americans have lost their property or livelihood at the hands of regulations banning food sales from home or unpasteurized milk, all quite publicly and with little recourse to the courts (thanks to a very permissive system of precedent when it comes to administrative actions).

Or we can go back to trade. Look at how President Trump’s bogus “national security” tariffs—which President Biden still insists on keeping around (so far at least)—have harmed numerous American businesses (even bankrupting some), forced others into a costly and Kafka-esque process for winning (begging for) an “exclusion” from the captured Commerce Department, and helped to foment the very market conditions Biden’s new EO claims to address:

There are many reasons for the price increase, according to experts. Trump-era tariffs on foreign steel shifted the balance of power from buyers to sellers.… The biggest concern, agricultural manufacturers say, is that, much like the meatpacking industry, the steel industry is experiencing major consolidation after many long-timers have gone bankrupt, leaving fewer players with more power. Goldman Sachs predicts that by 2023, about 80% of U.S. steel production will be under the control of five companies.

Ag manufacturers and retailers are already feeling the impacts. Cox, of Tarter Farm and Ranch Equipment, estimates prices have increased 24-32% across his industry in 2021. "You can hardly raise prices fast enough to cover what's going on," he said.

Nary a peep from Biden’s trustbusters here, however, because the “winners” in this case just so happen to be unionized steelworkers and influential companies in important “Rust Belt” swing states.

In each of these cases and plenty of others, there is a (theoretical, at least) justification for the laws or regulations at issue, and surely some such rules are needed. However, the current trend on both sides of the aisle is to act as if these risks don’t exist, that the power behind them can easily be controlled, or that their team will always be in charge.

Reality begs to differ.

Corporations (Almost Always) Have Limits

As Coaston notes, corporations can be plenty powerful, too, and even affect your livelihood in ways superficially similar to some of the regulatory actions noted above. From there, however, the differences between corporate power and state power are undeniably massive. No company today can lawfully and publicly deprive you of life or liberty. No company—without state backing, at least—can forcibly prevent you from seeking or creating alternatives when you don’t like (or have been denied) its product or terms. Refuse that company and you can lose business, but in almost all cases—including Big Tech—you have other options (and potentially future ones who see an opportunity for new customers and profits). Refuse the state’s terms, by contrast, and you eventually go to jail.

Central to this distinction is that, without the backing of the state, domestic and international markets will hold most corporations’ power in check, whereas state actors—especially unelected bureaucrats—are much less accountable, and only erratically and infrequently so (following court victories, elections, or new laws). Generally, a free market system with light regulation produces better outcomes for all participants (except those, perhaps, who previously benefited from state support)—even in important markets with a few large players. (See, for example, those freight and airline prices above, the items in that Journal editorial, or this brand new paper on the growing consumer surplus in the U.S. car market since 1980, even though the number of brands remained small.) Markets with heavy state intervention, by contrast, generate not only higher prices and less prosperity but also corruption and other political problems, frequently undermining the very social goals (equality, small businesses, etc.) those governments seek.

None of this means, of course, that markets or corporations are perfect, but it does mean that, when it comes to corporate power, the market is a better check than the state, and that embracing the latter to take on companies you don’t like comes with risks that the market just doesn’t have. Surely, there can be exceptions to these general rules, but that’s what they are—exceptions—and it’s how they should continue to be treated (via rigorous and objective analysis, clear limits, and brutal transparency). And adhering to these rules is particularly important, as the American Action Forum’s Doug Holtz-Eakin noted Monday, in a highly technical area like antitrust where the specific details of specific markets matter greatly.

Somehow, I doubt each side’s eager trustbusters very much care.

A friendly heads up: Capitolism is taking next week off. See you in two weeks!

Chart of the Week

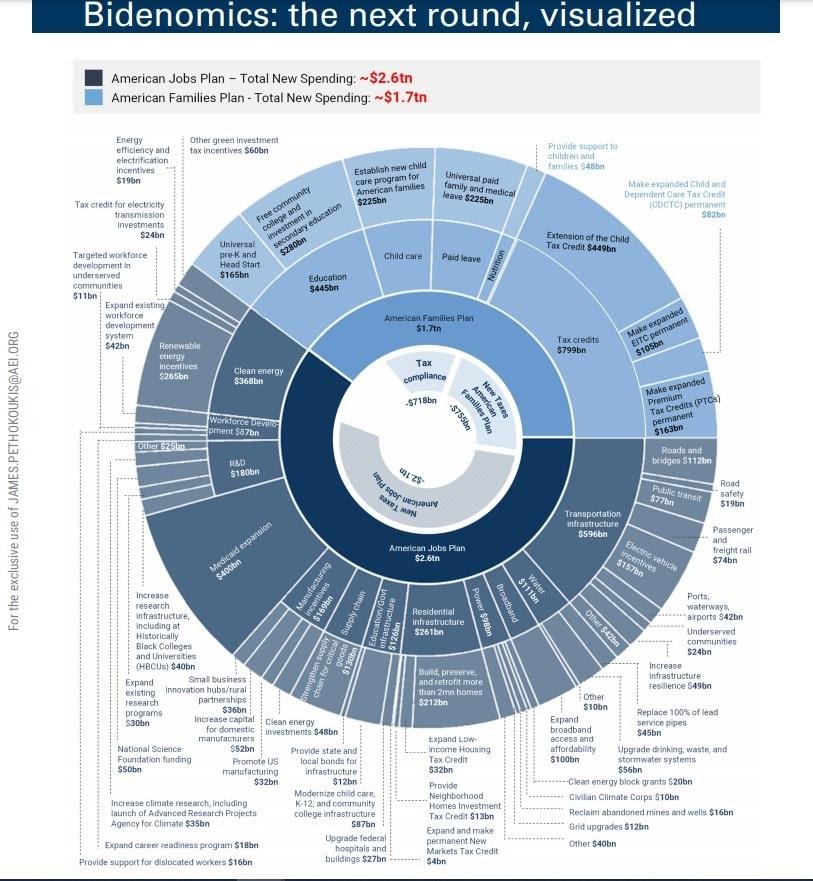

That’s no moon (via Jim Pethokoukis).

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.