Happy Sunday! There’s no denying that U.S. gymnast Simone Biles is the GOAT. But her storied comeback in the Paris Olympics and winning gold in the all-around Thursday may only be the second-most inspiring thing about that night thanks to her teammate, Suni Lee. It was all a joy to watch.

Nine years ago this summer, conservative Christians were grappling with the implications of the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision that struck down state-level bans on same-sex marriage. That included subsequent concerns about what the new legal framework meant for religious liberty protections in the United States, but also a realization that popular notions of human sexuality were moving farther away from historic Christian positions.

Conversations among Christians initially focused on how best to ensure that religious communities could conserve their beliefs while standing athwart a culture with largely divergent ideas about certain bedrock issues. Fast forward a few years later and many of those concerns about preserving those communities had turned instead toward the offensive—to supporting a political actor like Donald Trump and declaring that the classical liberalism at the foundation of democratic countries like ours was wholly insufficient for a shifting culture.

Today Jake Meador, editor-in-chief of the Christian journal Mere Orthodoxy, explains how so-called postliberal Christians embarked on such a path, helping us see the larger religious, political, and cultural forest even as we find ourselves still in the midst of the trees.

Jake Meador: After Virtue Came Strongman Politics

Though hard to imagine today, early in 2017 Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option debuted with a New York City launch party jointly sponsored by Dreher’s then-employer The American Conservative, alongside the religious magazines First Things and Plough. Dreher spoke at length before joining a panel of respondents that included New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, former Obama administration staffer Michael Wear (who has since started his own think tank), Harvard professor Jacqueline Rivers, and Randall Gauger, a pastor with the community of radical Anabaptist Christians who publish Plough. The panel was moderated by Plough Editor-in-Chief Peter Mommsen.

This event was, in many ways, the beginning of the postliberal conversation in conservative and Christian media. (The academic discourse around “post-liberalism” has far deeper roots stretching back several decades.) The goal of the media discussion was to find a way through the political morass created by expressive individualism and the erosion of given forms of belonging and meaning. Though it all feels hopelessly remote now, there was a time when such discourse in “conservative” media wasn’t primarily concerned with partisan politics. It certainly wasn’t about embracing illiberal right wing politics in the style of a “Protestant Franco.” It was about the cultivation and preservation of communities of Christian faith and virtue in a world where all the dominant social movements seemed to either be actively hostile or utterly indifferent to those communities.

How do I know this? Because I was there. I was sitting there in that room at the Union League in Manhattan, listening to these speakers and doing a great deal of my own thinking.

The story of how the postliberal conversation evolved over time to center on right-wing politics is a story not only about one specific conversation propelled largely by academics, but is also the story of how the American right and parts of the American church have been stretched, challenged, and changed by the events of the past 10 years. To understand how Donald Trump could well return to the White House (with a running mate who rose to fame via an interview with Dreher), then it is worth reexamining that story.

Unsurprisingly, the story begins in 2015, but not with the much-discussed escalator on which Trump descended before announcing his presidential campaign. Rather, the story begins in small town Indiana where some unguarded comments from the owner of a small family-owned pizza restaurant briefly attracted an early sort of cancellation from the American left.

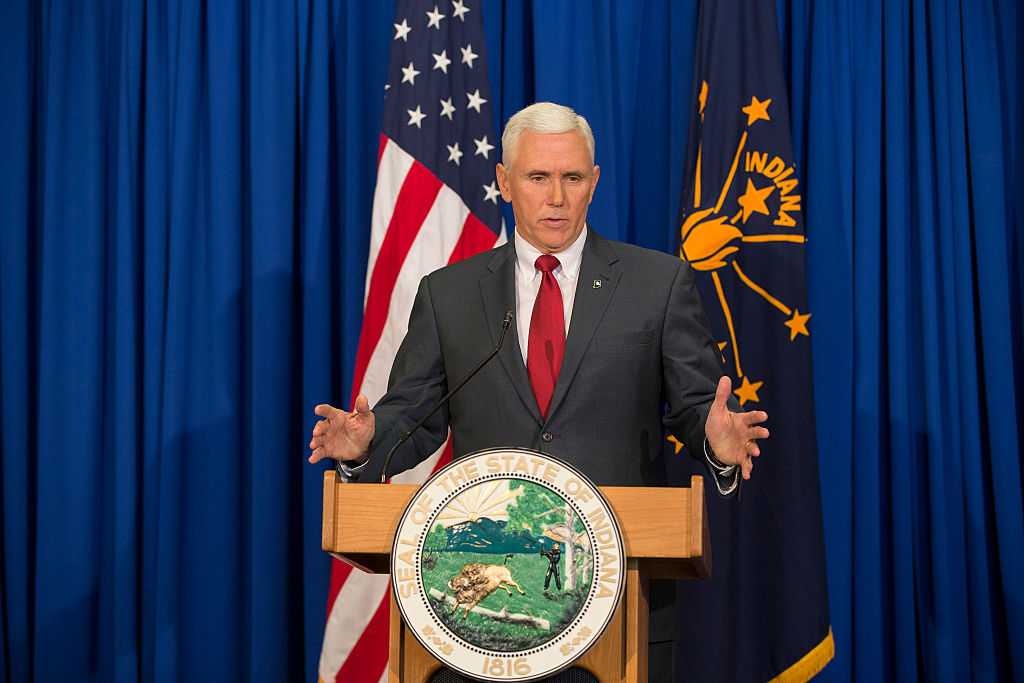

The context for this was an Indiana religious liberty bill—signed into law by then-Gov. Mike Pence in March 2015—that effectively mirrored the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) that became law in 1993. But in the context of the early 2010s and disputes over gay rights and redefining marriage, the provisions of such laws, once regarded as fairly banal, took on a far more controversial character. Tech giant Salesforce, which had a large presence in Indiana, threatened to reduce its investments and presence in the state if the law stood. Apple CEO Tim Cook also protested the law. The moral exemplars over at the National Collegiate Athletic Association, based in Indianapolis, also condemned the bill. And that was when the small town restaurant Memories Pizza grabbed headlines.

The small pizzeria, located in the 2,000-person town of Walkerton, captured the news cycle after a TV reporter phoned the restaurant and asked one of the owners if they would be willing to cater a same-sex wedding. The owner said they would not due to their religious convictions. What followed was a blitz of negative coverage, threats, and harassment targeted at the restaurant’s owners, which eventually forced the restaurant to temporarily shut down before eventually closing for good a few years later. At the end of the furor around the law, Atlantic columnist Conor Friedersdorf—who himself supports gay marriage—wrote a stinging rebuke to those who attacked Indiana so aggressively. But it would not be the Friedersdorfs who prevailed. Not only that, subsequent actions in Indiana hollowed out the provisions of the original RFRA bill.

The lesson that orthodox Christians took from Indiana was straightforward: The moral beliefs that you’ve always regarded as basic and even self-evident, that your faith has upheld for the entirety of its history, are now regarded as hateful and intolerable not only by left-wing political activists but by many in America’s business class. And not even the Republican Party will have your back if push comes to shove, as evidenced by the general lack of interest in religious liberty among Republican members of congress in 2015 and 2016.

This was a jarring realization for many, schooled as they were by nearly 40 years of Reagan-style fusionism in which the business class was one part of the GOP’s core coalition, which also included socially conservative Christians. Dreher spoke for many at the time when he wrote:

The reason (Indiana) was so shocking to many religious conservatives is because it showed us how things really are in this country — specifically, that religious liberty is far more imperiled than we previously believed. It’s not so much that people weighed religious liberty against gay rights claims and found them wanting; it’s that people didn’t seem to weigh them at all. It was naturally assumed, and assumed with great moral indignation, that of course religious people are entitled to no consideration in the face of anti-discrimination claims.

Still, conservative Christians in the media class at the time seemed to be less inclined to seek a political savior. Instead, they sought to shore up the foundations of their own communities, rededicating themselves to the practices of historic Christian movements and placing their hope in God’s providence to preserve them amidst a time of upheaval. Dreher’s own work at the time, which led to the publication of The Benedict Option, was not at all a retreatist head-for-the-hills screed as many wrongly said. Rather, it was primarily a prescriptive account of how Christian communities might survive a rapidly secularizing, dechurching West. Indeed, Christian writer and commentator Andy Crouch said as much at the time in his short remarks on the book, as did college professor Alan Jacobs.

Little surprise, then, that Dreher’s work was attractive to a wide audience that included the group assembled in Manhattan in 2017: the radical Anabaptist Bruderhof, a black church figure like Rivers, a center-left evangelical like Wear, and traditionalist Catholics like Reno and Douthat.

Arguing from Notre Dame philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre (who has disputed Dreher’s use of his work), Dreher held that the West had lost the ability to reason together about morality and ethics and instead adopted a solipsistic individualism in which the only rule is to express yourself (without harming others, preferably). As Burke’s “little platoons” that hold together civil society began to fail, giving way to self-creation through conspicuous consumption, common life withered. Indeed, private life withered as our internal worlds were often cut off from family, church, and neighborhood with only the desperate thirst for connection remaining in their wake. Small wonder so many of our peers now slake that thirst with everything from drugs to social media to porn. Even so, Dreher’s work invited others to fill out the picture he had begun to sketch.

Enter Notre Dame political theorist Patrick Deneen.

Deneen’s book Why Liberalism Failed came out in January of 2018, eight months after the launch of Dreher’s. It was a clear and obvious next step in the emerging traditionalist Christian critique of our cultural moment. For Deneen, the problem was not chiefly that our current moment had become hostile to Christian belief, though that was plainly true. It was, rather, that all of us living in the West were trapped in a deeply inhumane account of the world. This account, which Deneen called “liberalism,” was marked by the same hard individualism described by MacIntyre and Dreher. Even former President Obama positively remarked on Deneen’s book.

Why Liberalism Failed mainstreamed a certain sort of cultural and political critique that wasn’t really right or left. It could incorporate the wisdom of an agrarian Democrat like Wendell Berry, the pro-family leftist Christopher Lasch, and tech critics like Jacques Ellul. It’s not that everything Deneen said was good or right, but he synthesized much of the best social criticism of the past century. In fact, many parts of Deneen’s critique read more like the traditionalist leftism of Berry or Lasch than anything one might find on the political right.

This is where the postliberalism conversation lingered: How to create a culture of healthy dependence and mutuality contra the self-isolating, self-defeating individualism of the moment. At an event I attended in 2019, Deneen was asked to name something “illiberal” he had done in the past week. He replied that he made a point of going to Mass every day in the campus chapel at Notre Dame. “I think it is important that my students see their teachers kneeling,” he said.

So what happened to the version of postliberalism that considered problems of care, dependence, common life, and Christian virtue amid a lonely, angry, and addicted age?

An essay in the summer of 2019 essay supplies the answer.

It was then that then-newspaper columnist Sohrab Ahmari published a broadside against commentator David French in the pages of First Things. Ahmari charged French with endorsing a proceduralist form of politics that never tried to press toward ultimate questions but instead condemned our entire common life to a kind of indifferent shrug regarding such questions. As the integralist critic Adrian Vermeule had earlier put it in a piece for the postliberal Catholic magazine The Josias:

One of the most curious features of life under political liberalism—for present purposes, the doctrine that the central task of politics is to promote individual autonomy and to secure its preconditions—is that all politics and political conversation happens at one step removed, one meta-level up. Instead of pursuing substantive excellence and justice, we have circuitous conversations about statistical properties like “diversity”; instead of deciding what ought to be permitted, what condemned, we debate “civility”; instead of discerning truth, we quarrel over “religious liberty”; instead of protecting the most vulnerable, we conceal our vices and crimes under the rubric of “choice,” in both market and non-market spheres (although to be fair there are almost no non-market spheres left any more).

Ahmari contended we needed to reject Frenchian liberalism and instead seek “to fight the culture war with the aim of defeating the enemy and enjoying the spoils in the form of a public square re-ordered to the common good and ultimately the Highest Good.”

A more aggressive, confrontational style was the only way forward for traditionalist Christians, according to Ahmari. While he did not turn against the earlier post-liberal vision explicitly, he did imply that the envisioned communities imagined by that earlier vision could not truly flourish without political power backing them. For him, this meant support for Donald Trump was inherently baked into the postliberal political project because implementing such a vision for common life would require political power. Where politics had once been marginal relative to questions about virtue and common life, now they dominated.

Voters across the developed world have had enough of depoliticized politics. In the United States, this great “no” culminated in 2016’s election of Donald Trump. With a kind of animal instinct, Trump understood what was missing from mainstream (more or less French-ian) conservatism. His instinct has been to shift the cultural and political mix, ever so slightly, away from autonomy-above-all toward order, continuity, and social cohesion. He believes that the political community—and not just the church, family, and individual—has its own legitimate scope for action. He believes it can help protect the citizen from transnational forces beyond his control.

Thus Ahmari took what had been a broad conversation—primarily, though not exclusively, among Christians—about the preservation of virtue and the good life amid an individualist, technocratic society and shifted it into a debate about partisan politics and elections. To be postliberal was to be pro-Trump; to be liberal was to be anti-Trump.

The point here is not that the postliberal discourse prior to Ahmari’s attack on French was indifferent to politics or opposed to more assertive forms of political leadership. But it was not the central concern of the conversation. Return to the speakers at the launch party in New York: Aside from Reno, who had already endorsed him, not a single one of them to my knowledge voted for former President Trump the previous November. Indeed, in their own ways Wear, Dreher, and Douthat have all been remarkably ambivalent about the relative power government has in itself to advance the good.

Jake MeadorTo be postliberal was to be pro-Trump; to be liberal was to be anti-Trump.

A further change followed, perhaps of greater consequence still: The argument for how communities of virtue would be preserved changed. Prior to 2019, the argument was that they would be preserved through a robust and enduring sense of their own calling, fidelity to God, and care for one another. Beyond those ordinary practices of Christian faith and communal life, virtues could also be passed on within families, within friendships, and within the ordinary civil life of neighborhood and city, all of which could continue in the work of neighborliness, even as all around us those virtues were neglected and disdained. But in Ahmari’s argument, support for Trump—and hard political power—was necessary to preserve the virtuous way of life in America. And, since in this particular case the hard power that ought to be supported came in the form of a thrice married adulterer who paid a porn star for sex even while his third wife recovered from the birth of his son that inherently meant that the holder of power needn’t have any sort of virtue himself.

It is not terribly surprising that, in the five years since Ahmari’s essay, the postliberal movement has splintered and coarsened. Among Catholics, integralism became ascendant, even after Deneen had initially called its proponents “kind of crazy” in an earlier exchange prior to his joining up with them. That movement has now broadly collapsed, as Kevin Vallier has already documented at The Dispatch. Among Protestants, however, others latched onto Ahmari’s refashioning of the debate and quickly used it to advance their own project—which Ahmari himself has strongly opposed.

First, some embraced and amplified Ahmari’s claims about the necessity of morally indifferent, political strong men to secure a place for communities of faith and virtue to survive. This is why, to cite one example, New Founding partner Josh Abbotoy has in the pages of First Things called for a “Protestant Franco” to save America. The question of virtuous authority ceased to matter altogether, replaced by naked power as an effective way to reward friends and punish enemies.

Second, even as the account of how communities of virtue would survive shifted, so too did the account of what those communities even were. Bolstered by the claims of Stephen Wolfe in his book The Case for Christian Nationalism, the postliberal Protestants further argued that the communities we ought to preserve were not communities of faith and virtue, as defined in earlier iterations of the movement, but rather were communities of “natural” affection and mutual belonging. “Natural” in this case often had ethnic or racial overtones, as when Wolfe suggests that multi-ethnic nations are not really possible or when his occasional collaborator C. Jay Engel argues that America belongs to a class of people he refers to as “heritage Americans.”

The outcome is that the postliberal right, which began in conversations around The Benedict Option about how to better catechize young people and create thick communities of Christian belief has, in just under 10 years, shifted into something primarily partisan and quite often linked to white nationalism.

The irony in all this is that just as the postliberal right has become maximally partisan in its outlook and sensibilities, it has been abandoned by the very party and leader it looked to for security. Last month’s Republican National Convention included the GOP abandoning its commitment to the cause for life, leaving behind what little remained of its support for natural marriage, and platforming Amber Rose, a social media star who routinely posts pornographic images on her social media handles and only a few months ago praised Satanist groups for helping women secure abortions. Five years after Ahmari sold many on the notion that the authoritarian leadership of Trump was necessary to advance the good life, the party of Trump now resembles a more sexually progressive version of the 1990s-era Democratic Party.

What can be learned from this history? There was for many of us in the mid-2010s a profound sense that something was missing in our common life in America. Material abundance seemed, as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn warned, inextricably bound up with spiritual poverty. The false human story told by many progressives and conservatives alike in the years since Reagan, a story built around individual identity creation and the limitless pursuit of wealth through “free” (but to what end?) markets, often at the cost of transcendent truth, had left many people and places adrift.

The signs are not hard to identify even now: soaring rates of reported loneliness, an increased openness to euthanasia, shattered trust within communities, a strong anti-natal turn among many young Americans which has correlated unsurprisingly with freefalling birth rates, and all of that with a rising generation coming that is racked by anxiety and depression. These realities were present in 2015 and still are a decade later. If anything, the GOP’s capitulation on life and marriage suggests it will become even more entrenched on the American right as the GOP comes to be ever more dominated by what Matthew Walther has called the barstool conservatives. Yet the devouring need for truth, for genuine life together, and for higher goods than a purely individualistic freedom remain.

To where shall we turn, then? For those of us still seeking a better politics, we might consider the words of the White Rose movement, a group of what might be termed “radical liberals” who arose in the middle of the German Third Reich. The White Rose told their readers they would be Germany’s “bad conscience.” Through the written word and their small bit of organizing and shared life they sought to call Germans back to truth, to condemn the evils that then pervaded Germany’s public life, and to suggest that another way was possible. But that way was marked by strikingly liberal virtues—tolerance, for example, as well as a healthy commitment to some forms of pluralism.

We can and should recognize that the problem is not “liberalism,” whatever that meant, and that the plain facts of many of our lives today are themselves loud vindications of American democratic life at its best. And then, from within the home that democracy has furnished us, we should call our readers and friends and, indeed, our enemies to the shared project of pursuing the truth together, following it wherever it leads. Indeed, many of the finest friendships I have known are with some of the other guests in attendance that night in New York.

Is there hope for such a project? Is this vision too small? Here I am reminded of the words of one of the thinkers who inspired me at my most postliberal and who inspires me still: “There never was much hope. Only a fool’s hope.”

More Sunday Reads

- For our website on Saturday, investigative reporter Warren Cole Smith reviewed a new book by Daily Wire reporter Megan Basham in which she argues evangelical institutions have been infiltrated by leftist sellouts. “Basham is right that many ‘shepherds’ are, in fact, ‘for sale,’” Smith wrote. “But the unintended irony—and fundamental flaw—of her book is that the corrupting money is not on the evangelical left, as she claims, but on the populist right. The rise of such organizations as Turning Point USA (and its subsidiary Turning Point Faith), the Epoch Times, and The Daily Wire itself—organizations that combined bring in hundreds of millions of dollars in annual revenue—bear witness to the financial benefits of pandering to populists.”

- Ryan Burge has been a political science professor during the week and a pastor on the weekends—until last month. Burge, who has become well-known nationally by tracking church attendance and other religious trends, wrote for Deseret News about the recent gut-wrenching decision he and his congregation made this year: “We picked a date: July 21. That would be the last time that the faithful few of First Baptist of Mount Vernon, a church founded by hardscrabble pioneers in 1868, would gather together to worship. I am having a hard time wrapping my head around the fact that I get asked all the time, by pastors, denominational leaders and interested observers, about ways to grow a church. I guess people assume that since I spend my days digging through religion data, that I should have been able to uncover the secret to getting people back into religion. It takes everything in my power to not say to them, ‘My church went from 50 people to less than 10 under my watch. If I knew anything about how to grow a church I would have done it by now.’”

A Good Word

For Christianity Today, Hannah McClellan reports on how some people with Native American roots are reconnecting with the language and culture of their heritage: Bible translation apps. “Kenny Wallace doesn’t have a lot of people to talk to in Choctaw. But he does have a Bible app with a new translation of Scripture in the Indigenous language that his ancestors spoke,” McClellan writes. “And it has an audio sync feature that allows him to listen to the words aloud, to hear how they sound. ‘Sometimes, that’s the only Choctaw voice I ever hear,’ Wallace told CT. ‘Not only is it feeding my soul, but it’s actually feeding me culturally as well.’”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.