Hi and happy Sunday.

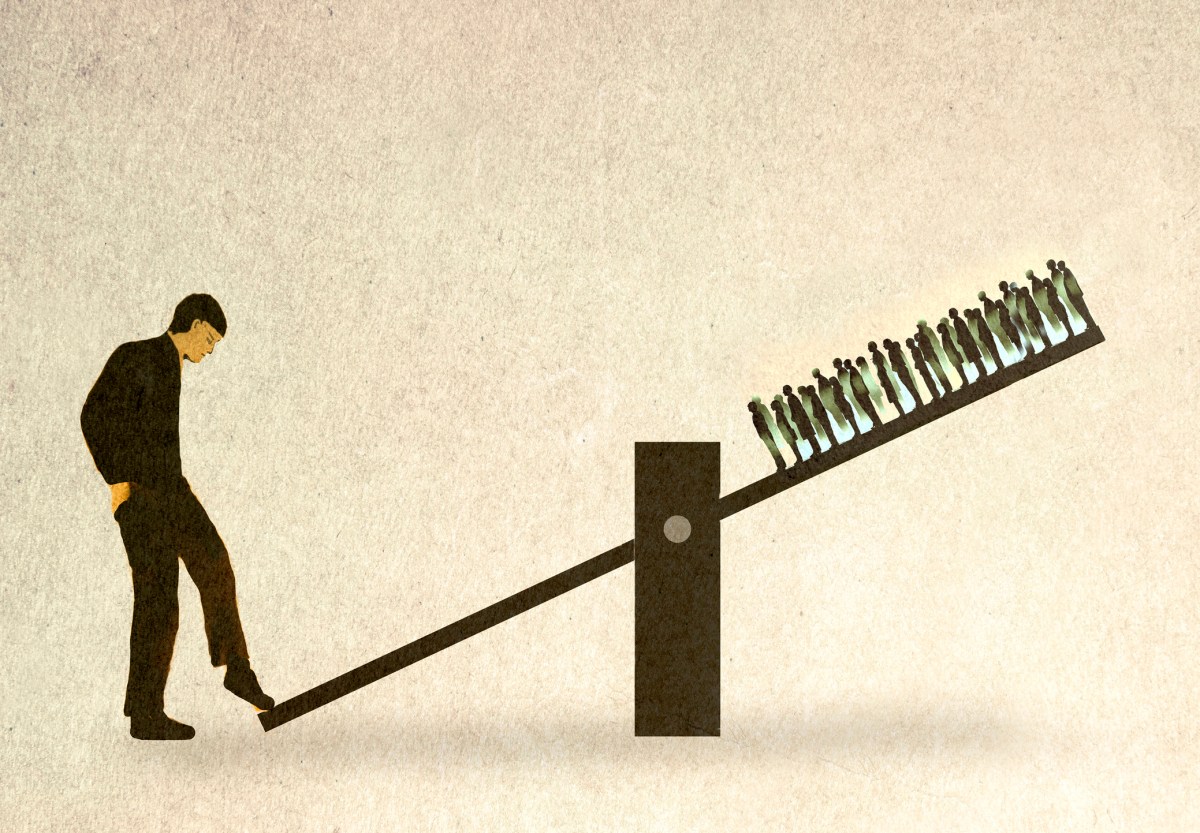

Americans have always had a fraught relationship with authority. A healthy skepticism was built into our founding documents so that civically our bent is toward questioning the natural limits of our governing authority.

That stretches into the realm of religion, too. In some ways, the story of the last 25 years of American Christianity has been that of bad religious authority: abuse scandals, unhealthy understandings of church and politics, and sometimes cultish fads. So with so much bad authority, how do we know what good authority looks like?

Writer and editor Bonnie Kristian argues this week that Christianity—when practiced in healthy communities—provides an answer that can potentially reach even beyond the sphere of religion.

Bonnie Kristian: How Christianity Helps Us Recognize Good Authority

I could begin here with some anecdote of abuse of authority—the latest scandal of a megachurch pastor’s improprieties or the newest headlines of corruption, hypocrisy, or overreach from Washington. But what would be the point? In the days between when I write this essay and you read it, fresh scandals will emerge. Even newer headlines will appear. The stories that now come to mind will by then be but half-remembered, old installments in a never-ending serial of authority misused.

This is a comprehensible story for Americans, for suspicion of authority is core to our political culture, fundamental across deep partisan fractures. Our founding myths and documents alike assume that a default skepticism of authority is not only reasonable but a necessary habit of mind. Our history is busy with examples of hard-won victories over authority stolen, disfigured, and exploited.

And so we easily agree, as Lord Acton wrote in 1887, that “[p]ower tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” And Acton’s lesser-known affirmations from the same letter seem just as commonsensical, at least when applied to our political opponents: “Great men are almost always bad men.” “There is no worse heresy than that the office sanctifies the holder of it.” If we judge the powerful by a different standard than the powerless, it should be a harsher rule “as the power increases.”

As an American—and a political libertarian and Protestant Christian, no less—I share all that skepticism. Indeed, some of the severest language in the Bible is reserved for authorities who abuse their power, especially spiritual authorities and those whose power is backed by force.

Over and over the Old Testament prophets speak woe “to those who make unjust laws, to those who issue oppressive decrees, to deprive the poor of their rights and withhold justice from the oppressed of my people, making widows their prey and robbing the fatherless” (Isaiah 10:1-2). God threatens to make “oppressors eat their own flesh” (Isaiah 49:26); he demands repentance from princes who deal in “violence and oppression” (Ezekiel 45:8-9).

In the New Testament, Jesus describes part of his mission as freeing the oppressed (Luke 4:18). He speaks more bluntly to and about religious leaders than the broader crowd (e.g. Matthew 3:7, 23:1-3), anticipating confusion from the public (Mark 4:11-12) but expressing shock when a religious scholar doesn’t understand his teaching (John 3:10). The Apostle Paul describes Christ’s victory over evil in part as his destruction of wrongful “dominion, authority, and power” (1 Corinthians 15:22-28), and the Epistle of James warns that those “who teach will be judged more strictly”—and, consequently, that many should think twice before shouldering the authority of instruction (3:1).

If we stop with that sketch of the biblical record, however, we have at best half the picture, and this brings me to a worrisome aspect of our contemporary discourse on authority. I find something distorted and distorting in how seemingly all our public conversations concern authority in its worst and most illegitimate expressions: self-serving public servants, predatory priests, lawless law enforcement.

The wariness Acton expressed, the critiques in our Declaration of Independence and constraints in our Constitution, the extra measures of scrutiny and accountability for authorities that we see in Scripture—these are hosted by an assumption that good and rightful authority can and does exist. The point of circumspection and safeguards is to push authorities toward wielding power in a righteous and trustworthy way.

What of that assumption today? We still agree in theory that there’s such a thing as good authority. But, in practice, do we know what it looks like or how to submit to it? That very word—submit—makes our skin crawl. Authority is more likely to bring to mind authoritarian than any positive association. Why, we ask of any would-be prince or teacher, do you want power over me? What’s your game?

Christians are no exception in this. We can be just as leery of authority as any of our compatriots (and just as accepting of abusive authorities when we are deceived or self-deceiving). But we have—or could and should have—a resource many other Americans lack: a tangible, accessible model of authority with whom we can learn to recognize and relate to good and rightful authorities wherever we encounter them, including in politics and public life.

That authority is the pastor of the local church and, in some traditions, other local or near-local leaders like elders and bishops (Hebrews 13:17). If Christians were familiar with and practiced in heeding good authority within the church, perhaps we'd be better equipped to recognize and foster it in the wider world.

The equipment I have in mind is not some kind of conscious rubric against which we’d compare leaders of all kinds. What I’m hoping is that we’d develop a reliable instinct about authority both in its formal exercise (does this person seem to be operating within the appropriate bounds of their office?) and in terms of personal character (does this person seem to be reasonably virtuous and well-intended?), a feel for integrity and legitimacy that would operate above political alliances or policy preferences or personal expertise. We’d develop sound judgment informed by long familiarity with–and due submission to–good authority in a pastoral setting.

I understand the discomfort many may instinctively feel at the notion of pastors exercising authority. I feel it too. Isn’t that cult stuff? Why should a pastor get to tell me what to do? If your hackles are raised, bear with me for a moment and think through what I’ve found to be an illuminating example: Suppose your pastor told you to delete your account on X (formerly Twitter). Would you feel obliged to do it?

I’ve posed this question to friends, colleagues, and other fellow Christians for several months now, and by far the most common response has been reflexive resistance: Twitter is bad, yeah, but I’d bristle if my pastor told me to log off. Even with all due caveats (assume you’re in an orthodox and healthy church; assume the pastor truly has your best interests at heart; assume you’re able to talk it over and that the pastor might retract the instruction if you presented some new or mitigating information) as well as recognition that there’s no real enforcement mechanism, this has not been a popular idea.

That reflex strikes me as exactly the problem. In this scenario, we’ve established that the guidance is wise, the pastor’s motives benevolent, and the obedience voluntary. That bristling is not at the content, aim, or enforcement of the direction but at the idea of authority itself, the idea that another adult would give us an instruction and we would be expected to submit. And if we can’t recognize good authority when we encounter it in the intimacy of our local congregation, how will we recognize it across the distance of the national stage?

Two final notes may make this proposal more intelligible. One is the reminder that this vision of pastoral authority, for 21st-century Americans, takes place in the secularity famously described by the philosopher Charles Taylor in A Secular Age. That is, just as we know faith is one option of many, so we know we can leave any church at any moment. This is what I mean when I say there’s no enforcement mechanism: We’re in a post-Reformation world with no established church and ever-loosening moral norms. Nothing a pastor can say is binding in the way it would’ve been in a small, premodern village on the parish model.

So if we’re free, why submit to guidance that—though theologically, ethically, and relationally sound—may be unwanted, unpleasant, and difficult? An analogy I’ve found helpful and biblically resonant (1 Corinthians 9:24-27) is one I owe to my friend Erica Ramirez: Your pastor is like your personal trainer.

She can’t literally force you to take her exercise and nutritional advice, but when you hire her to be your trainer and help you work toward a mutually agreed fitness goal, you must do what she says if you want to remain her client. You recognize her authority not because she forces you but because, in a sense, it is consonant with the truth. You do what she says not because it is never daunting or painful but because you recognize that she is helping you move toward the virtues you seek.

My second note is that even that analogy and my Twitter example might be too robust, because good pastoral authority in action may only rarely look like explicit direction. Sometimes that will be necessary (e.g. 2 Corinthians 13:9-10; 1 Thessalonians 4:1-2; Titus 2:15). Yet more often, as a seasoned pastor told me, it will look like gentle suggestions and thoughtful questions to help the congregant choose the good for himself. It will compel us not with strident tones or threats, but because truth is inherently compelling.

In the process, it will teach us what authority looks like when it is used aright. It will help us develop a feel for good authority, and give us an authority to identify it where we find it, a way to render a public service by verifying a public good.

A version of this essay was originally published in the Center for Christianity and Public Life's 2024 Journal of Ideas.

Michael Warren: J.D. Vance’s Holy War

On the website Friday, Michael Warren took a closer look at the war of words Vice President J.D. Vance started with the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops last week when he said the bishops were more concerned with their “bottom line” than in genuinely helping migrants to the U.S.

The vice president had picked an easy target: a faceless bureaucracy that at first glance has little to do with the everyday lives of churchgoing Catholics in their parishes. But Vance’s snap at the bishops had more than a little venom to it. This was not a “agree to disagree” moment, one employed by Catholic politicians in both parties when one of their positions inevitably comes into conflict with the teachings of the church. Vance was questioning the sincerity and good faith of the bishops on one of the most visible parts of Catholic ministry: the care and defense of the vulnerable.

Some Catholic stakeholders in Washington and beyond worry that by suggesting the church is benefitting financially from the resettlement program, Vance opens a door for bigots. Anti-Catholic nativists in the 19th and early 20th century often cast the church as greedy, seeking public funding for their parochial schools or as payouts to immigrants from the urban political machines. Vestiges of those anti-Catholic sentiments remain enshrined in some state laws to this day.

Aside from the substance of Vance’s accusation itself, Michael also reports on the implications of the newly installed vice president picking a fight with a group that could be a political ally:

With the Vatican looking askance at the new administration and Pope Francis installing a Trump critic to lead the archdiocese in the nation’s capital, it’s unclear what the upside is for Vance to alienate the relatively conservative conference of American bishops on week one—especially after Catholic voters preferred Trump over Kamala Harris in November by 20 points.

But like president, like vice president. There appears to be little patience from either Trump or Vance for criticism from those who might otherwise be allies.

The Dispatch Faith Podcast

The new Trump administration’s early spate of executive orders and directives have rocked much of the federal government, but its orders regarding immigration and U.S. aid have reached far beyond the Beltway, upending nonprofits working with migrants and refugees. For the Dispatch Faith podcast I spoke to two people whose organizations now find themselves in that breach: Catholic Bishop Mark Seitz, of the El Paso, Texas, diocese; and Matthew Soerens of the Christian relief agency World Relief. Seitz and I discussed how Trump’s executive orders are affecting the network of migrant shelters his diocese operates along the southern border, Vice President J.D. Vance’s recent barbs toward the Catholic Church on immigration—and the much ballyhooed reference he made to the principle known as the Ordo Amoris. Soerens, meanwhile, explained to me how the Trump administration’s orders are throwing into uncertainty a group of legal migrants to whom the U.S. government has already made commitments: refugees. These conversations usually are posted to our members-only podcast feed, but this week’s episode is unlocked for everyone.

More Sunday Reads

- Taken at face value, the ascendance of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.—whose radically pro-choice record and questionable moral history—should be a nonstarter for many Christians. But, as Ruth Graham put it in the New York Times this week, Kennedy has a dedicated fan club among conservative Christian moms: “Anna Gleaton and her husband operate a small homestead on 60 acres outside Gainesville, Texas, a rural town just south of the Oklahoma state line. Their farm, which operates on the principles of regenerative agriculture, includes pigs, goats and a dairy cow, which Ms. Gleaton described as ‘an adventure.’ Another adventure: home-schooling their nine children, ages 2 to 16. Ms. Gleaton, 36, describes herself as a conservative Christian, and she voted for Donald Trump in 2016, 2020 and 2024. This time, she had not been optimistic that he would focus on issues that most concern her, including contaminated soil and waterways, factory-farmed meat and the lobbying by agricultural corporations. But Ms. Gleaton now gets goose bumps when she looks ahead, largely because Mr. Trump has nominated Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as head of the Department of Health and Human Services. … ‘He’s saying what parents like me have been thinking for a long time,’ said Nicki Truesdell, a mother of five and a home-schooling activist in Gainesville. ‘In the “crunchy” world, he’s very well known and loved.’”

- For our site, professor of international affairs Jennifer Brick Murtazashvili reviews The Islamic Moses by Mustafa Akyol. “The central thesis of the book is that Islam and Judaism share much more than a monotheistic ethos. Drawing on history and theology, Akyol traces how the Quranic narrative of Moses, which dominates Islamic scripture, parallels and complements the Jewish understanding of this foundational prophet. Both Moses and Muhammad shared prophetic journeys, both led their communities from oppression to freedom, and both faced opposition from powerful leaders,” she writes. “Akyol notes that Moses is central in the Quran because he represents justice, faith, and perseverance and served as a model for Muhammad. Akyol also argues that the story of Islam is inseparable from that of Judaism and that, in many ways, Islam has positioned itself as an extension of Judaism, sharing its core tenets while seeking to universalize its message. Akyol further suggests that Judaism serves as a ‘midwife’ for Islam, especially during its early years, because its monotheistic beliefs, legal traditions, and prophetic narratives provided a foundation that influenced the development of early Islamic theology, law, and religious practice. Throughout the book, Akyol points out the parallels between Islamic law (Sharia) and Jewish law (Halakha), the creative symbiosis between Jewish and Muslim communities during the medieval period, and the mutual enrichment of Jewish and Islamic rationalism during the Golden Age, which lasted from the eighth to the 13th centuries C.E.”

- Everything about Tulsi Gabbard has come under the microscope since Donald Trump nominated her to be the director of national intelligence. That has included a particular branch of Hinduism, as Richa Karmarkar reports for Religion News Service. “Gabbard was raised in the Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition — a sect, or sampradhaya, with a special affinity for Lord Vishnu’s incarnation of Krishna — a blue-skinned deity often pictured with his consort, Radha, and with his favorite instrument, the flute. Gabbard’s particular branch of the sect is the Science of Identity Foundation, a group founded by Siddhaswarupananda, also known as Chris Butler, who broke from ISKCON — a Gaudiya Vaishnava group more commonly known as the Hare Krishnas — in 1974. The charismatic Siddhaswarupananda founded SIF in his home state of Hawaii, where Gabbard’s parents joined him — her father, who is of Samoan and European ancestry, converting from Catholicism. (Some sources refer to him as a ‘Catholic Hindu.’) An offshoot group led by a guru like Siddhaswarupananda is nothing out of the ordinary in Hinduism. Gurus are often worshipped or even deified for their ability to pass along teachings to lay believers.”

A Good Word

For the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Jack Hajdenberg profiles Millie Baran, a 99-year-old Holocaust survivor who, as of today, will be able to add “jazz artist” to her résumé. “Baran, a Forest Hills resident who loves singing but has no professional music experience, has partnered with Albert Marquès, a composer, pianist and a New York City public school music teacher who originally hails from Barcelona. Marquès’ project, Ampl!fy Voices, uses music to tell the stories of underrepresented voices, including men on death row, a free speech advocate in Spain who went to prison for criticizing the king and, now, Holocaust survivors. For this iteration of Ampl!fy Voices, titled ‘Mir Zaynen Do,’ (‘We Are Here’ in Yiddish), Marquès is working with a team of six Ashkenazi Jewish musicians who play piano, guitar, alto sax, bass and drums — plus Baran’s spoken word performance, in which she narrates her own testimony,” Hajdenberg writes. Baran later explains: “When you read things in the books, in the newspapers, it’s one thing. It’s entirely a different thing when you hear it, like they say, from the horse’s mouth,” Baran said in a Zoom interview. “You hear it when a person went through all those sarot [storms], tsuris, so, as we will say, entirely different than you read it in the paper. So I want, for posterity, maybe somebody will hear it, maybe somebody will see it.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.