Is it possible for a book to feel both timely and like a relic from a different era? In the case of The Islamic Moses, by the Turkish writer Mustafa Akyol, the answer is yes. The book was completed before the seismic events of October 7, 2023, shattered Jewish-Muslim relations, and the chasm between these communities has only grown wider since.

Still, by looking back into centuries of history, this book offers a vision for a path forward. It’s a thoughtful and compelling exploration of the shared theological, historical, and cultural threads that connect Islam and Judaism, and it therefore challenges the zero-sum narratives that prevail in contemporary discourse.

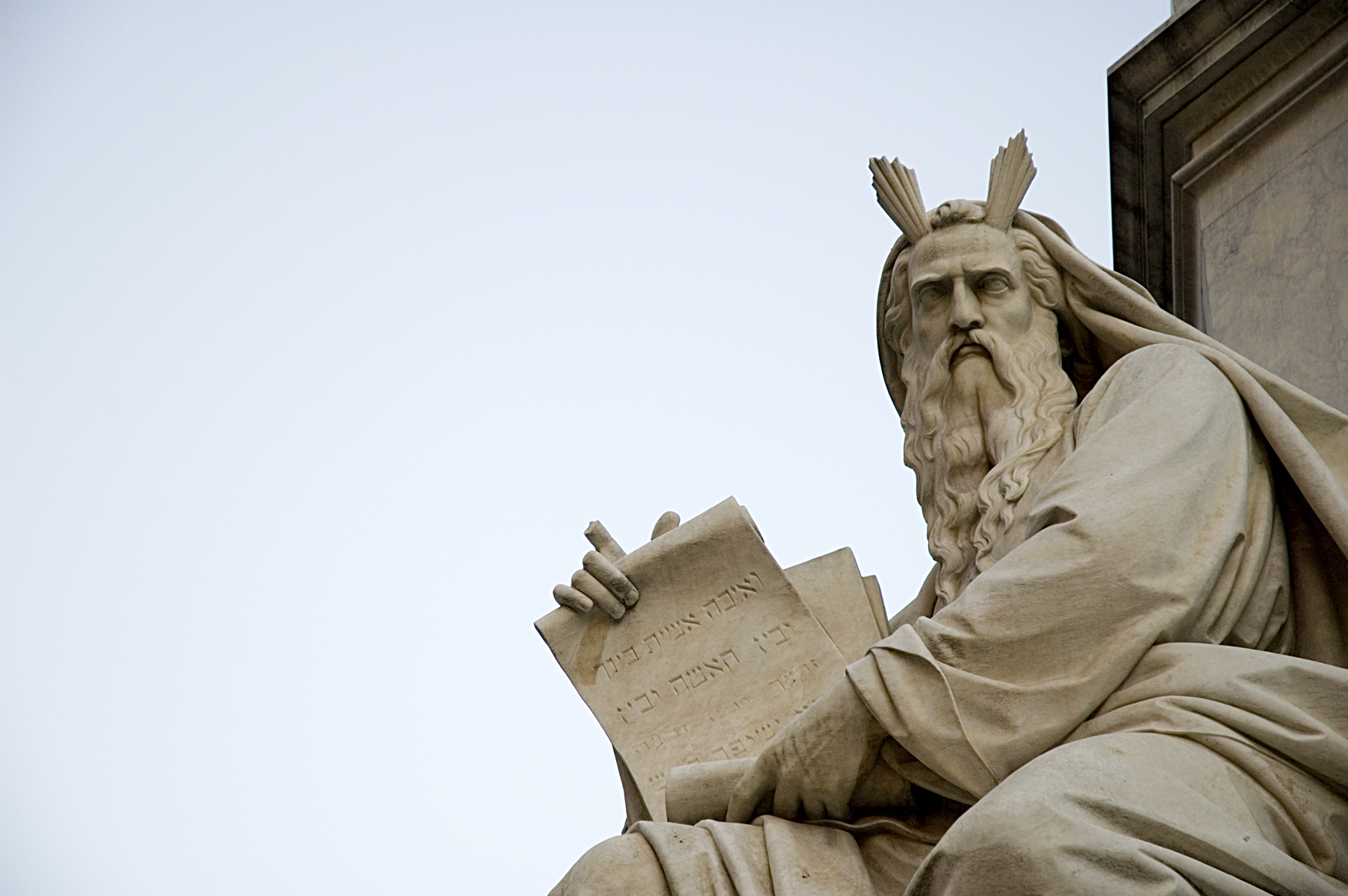

The central thesis of the book is that Islam and Judaism share much more than a monotheistic ethos. Drawing on history and theology, Akyol traces how the Quranic narrative of Moses, which dominates Islamic scripture, parallels and complements the Jewish understanding of this foundational prophet. Both Moses and Muhammad shared prophetic journeys, both led their communities from oppression to freedom, and both faced opposition from powerful leaders. Akyol notes that Moses is central in the Quran because he represents justice, faith, and perseverance and served as a model for Muhammad. Akyol also argues that the story of Islam is inseparable from that of Judaism and that, in many ways, Islam has positioned itself as an extension of Judaism, sharing its core tenets while seeking to universalize its message.

Akyol further suggests that Judaism serves as a “midwife” for Islam, especially during its early years, because its monotheistic beliefs, legal traditions, and prophetic narratives provided a foundation that influenced the development of early Islamic theology, law, and religious practice. Throughout the book, Akyol points out the parallels between Islamic law (Sharia) and Jewish law (Halakha), the creative symbiosis between Jewish and Muslim communities during the medieval period, and the mutual enrichment of Jewish and Islamic rationalism during the Golden Age, which lasted from the eighth to the 13th centuries C.E. This period featured the emergence of prominent Jewish thinkers like Moses Maimonedes, who was deeply influenced by Muslim philosophers such as Al-Farabi, Avicenna (Ibn Sina), and Averroes (Ibn Rushd).

This, of course, conflicts with the more violent parts of the two faiths’ relationship, and Aykol highlights the sometime subjugation of the Jewish people under Islamic rule. This was true of the earliest fraught encounters during the Medinan period—during the life of the Prophet Muhammad when he and his followers lived in Medina—when Jewish people were expelled and had their property confiscated, and Jewish men who were accused of plotting to assassinate Muhammad and conspiring with his opponents were executed. It was also true during Ottoman rule, when Jews and Christians were governed by the dhimmi system that allowed Jews to practice their religion, own property, and engage in commerce, but also subjected them to restrictions such as a poll tax and prohibitions on bearing arms and holding certain positions of power over Muslims. As Akyol notes, this second-rate classification also contributed to violence against Jews, expulsions, and forced conversions.

Akyol’s book, then, also implies a critical question: How do we reconcile the shared foundations of the two traditions with the often stark divides between people of these faiths, especially today? One way might be through further theological study; as he points out, religious texts and histories are not static, and are constantly reinterpreted in response to contemporary realities. But those contemporary realities are not exactly helpful; Jews in Saudi Arabia are denied citizenship, and Jewish schools in Iran have been forced to incorporate Islamic teaching. And of course, there was the mass expulsion of almost a million Jews from Middle Eastern states after the establishment of Israel, leaving almost no significant Jewish populations left elsewhere in the region.

Indeed, if the history of Jewish-Muslim relations has allowed for some coexistence, Akyol points out that this era of history may have been severed with the establishment of the state of Israel. According to Akyol, many Arab governments and populations perceived local Jewish populations as potential collaborators with Israel—even though many Jews had no connections to this new state. The humiliating Arab defeat in the 1948 Arab-Israel War, where armies of five Arab states (Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon with the support of Saudi Arabia and Yemen) invaded Israel the day after the declaration of the establishment of the state, didn’t help. And ever since, Israeli relations with their Muslim-majority neighbors have been shaky at best.

This leads us to a question: Coexistence between Jews and Muslims was possible when Jews were minorities throughout a Muslim empire. But is it possible when Jews have their own state and are no longer subjects but citizens?

Akyol wrote the book at a time of greater hope: The Abraham Accords had just normalized relations between Israel and many Sunni Arab states for the first time, and in the days before Hamas’ brutal attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, it seemed that Saudi Arabia was on the verge of recognizing the state of Israel.

Still, all is not lost. Some believe a solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict is still attainable. For example, Ronit Levine-Schnur and Daphna Joel, professors at Tel Aviv University, argue that a regional alliance with Arab states and Israel—as we are seeing with the Abraham Accords—has real potential to end conflict between Israel and its Muslim neighbors but also—in the long term—help promote a resolution of the Israel-Palestine conflict. A regional security alliance between Israel and anti-Iranian states, they say, would be a “victory for generations” in the region.

The growth of the Abraham Accords into a meaningful Abraham Alliance may be able to produce regional cooperation, economic growth, and a sense of shared prosperity for all in the region. While many look for peace from below, these agreements between states may allow individuals and communities to come together in ways they had never before.

The Islamic Moses is a valuable contribution to this endeavor, offering both a glimpse into a shared past and, to this reader, a potential for a more interconnected future. By examining the historical and theological ties between Islam and Judaism, Akyol provides a framework for reimagining these relationships in a way that acknowledges both the challenges and the opportunities of our time.

Akyol drafted his concluding chapter as the Israel-Hamas war broke out. He watched as global opinion on that war split along religious lines, creating a deep fissure that may take generations to heal. But while Akyol concludes with a pessimistic vision, I am more optimistic. Broader regional trends, such as the Abraham Accords, offer genuine reasons for hope. Notably, none of the countries involved in these agreements terminated them in response to the recent war, signaling a turn towards long-term cooperation.

The new ceasefire and hostage deal may also signal a path toward peace, including the possibility of long-elusive acceptance of Jewish sovereignty among Arab states. Such acceptance could pave the way for coexistence and a revival of the Judeo-Islamic tradition that Akyol so compellingly chronicles—a tradition that once thrived, and maybe could again.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.