Hi, and happy Super Bowl Sunday to all who celebrate (including those of you, like me, who can’t really bring yourself to root for either the Chiefs or the Eagles).

Vice President J.D. Vance’s recent criticism of Catholic bishops for their work with refugees and migrants was a surprise on many fronts. Not because Vance—whose No. 1 priority as vice president seems to be advocating for his boss’s policy preferences—took a hard line on immigration. What was really shocking, says writer Dan Hugger, were the arguments he employed and his understanding of the Catholic Church’s relationship to the U.S. government. That, and perhaps the fact that Vance also parroted arguments that have been used against U.S. Catholics for decades.

Dan Hugger: Why J.D. Vance Is Wrong About the Catholic Church’s Mission

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ (USCCB) response to President Donald Trump’s deluge of early executive orders was a mixed offering. USCCB President Archbishop Timothy Broglio criticized orders concerning the “treatment of immigrants and refugees, foreign aid, expansion of the death penalty, and the environment,” while praising others that “can be seen in a more positive light, such as recognizing the truth about each human person as male or female.” Broglio reiterated that neither the Catholic Church nor the USCCB is a partisan organization and that, “No matter who occupies the White House or holds the majority on Capitol Hill, the Church’s teachings remain unchanged.”

The statement was unremarkable in that it was consistent with recent USCCB positions. Catholics of good will can and do differ with their national bishops’ conferences and among themselves on matters of prudential politics. That Vice President J.D. Vance, himself a Catholic, saw fit last month to take exception to some of the criticisms offered by the USCCB in an interview with CBS News a few days later was also unremarkable: There is a long tradition of Catholic politicians of all parties doing so.

But the way he took exception—by casting aspersions on the motives of the USCCB and implying that the bishops are acting against the republic—was unusual. Attacks on the church’s leadership, both foreign and domestic, as acting in their own interest and against those of the American people have long been a rhetorical staple of anti-Catholicism, but this sort of rhetoric is perhaps a first for an American Catholic politician. His theological defense of the Trump administration’s immigration policies days later on Fox News—invoking the ordo amoris (order of love)—might well be the first such use of that argument in 21st century politics. The combined effect of traditionally anti-Catholic rhetoric followed by novel appeal to the church’s social teaching was deeply strange.

The most obviously indefensible—and least interesting—of these arguments was the impugning of the USCCB’s motives. Vance called on the USCCB to “actually look in the mirror a little bit and recognize that when they receive over $100 million to help resettle illegal immigrants, are they worried about humanitarian concerns? Or are they actually worried about their bottom line?”

The USCCB issued the following statement in response, emphasizing that the refugees it serves do indeed have legal status and are not “illegal immigrants”:

Faithful to the teaching of Jesus Christ, the Catholic Church has a long history of serving refugees. In 1980, the bishops of the United States began partnering with the federal government to carry out this service when Congress created the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP). Every person resettled through USRAP is vetted and approved for the program by the federal government while outside of the United States. In our agreements with the government, the USCCB receives funds to do this work; however, these funds are not sufficient to cover the entire cost of these programs. Nonetheless, this remains a work of mercy and ministry of the Church.

The USCCB regularly publishes its financials, and with a little diligence you can see for yourself what funding the USCCB receives for refugee resettlement, from whom, and where it goes. Brendan Hodge, writing for The Pillar, published an excellent story “Is migration padding the USCCB ‘bottom line’?” that does just that. His answer to the titular question of the article:

Given that the USCCB has spent an average of $5 million more on refugee and migrant services each year it has received from the government, the answer to that question would seem to be no. In fact, if the principal concern was the “bottom line,” the USCCB would seem better off without any involvement in migration and refugee resettlement programs at all.

Less easy to untangle is the vice president’s contention that the USCCB has “not been a good partner in common sense immigration enforcement that the American people voted for, and I hope, again, as a devout Catholic, that they’ll do better.”

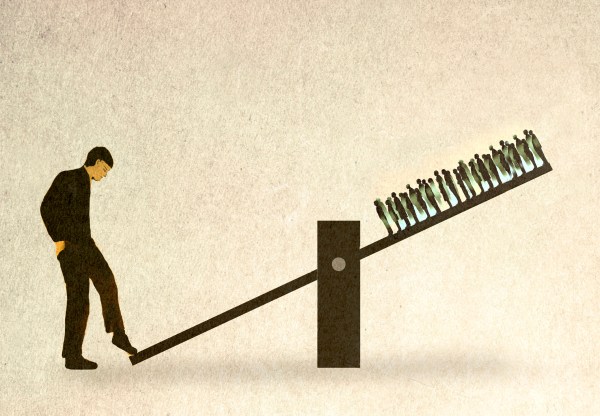

Vance’s argument seems to be that the church has a responsibility to support, in an undefined sense or manner, the policy positions of the government of the United States. The weight of the witness of scripture, the history of the church’s conflict with states, and the American Catholic experience are decidedly against this approach.

The relationship between religion and the state has been vexed throughout history. Prophets and kings have often had difficult relationships. The Lord Jesus Christ himself proposed the most elegant solution when he commanded that we, “Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s; and unto God the things that are God’s” (Matthew 22:21). The English historian Lord Acton wrote that with this striking answer Christ “gave to the civil power, under the protection of conscience, a sacredness it had never enjoyed, and bounds it had never acknowledged; and they were the repudiation of absolutism and the inauguration of freedom.”

The creation continues to groan (Romans 8:22) for its acceptance by the principalities and the powers of the world (Ephesians 6:12). Civil power has often exceeded its natural bounds, and churches have also periodically failed to recognize the civil power’s sacredness. Bishops and emperors fared little better in practice than their ancient forbearers. Popes and early modern states, in the thrall of Reformation and Counterreformation both, were often at odds—in ways that compromised them and continue to compromise their successors.

Important aspects of church governance including the appointment of bishops, seminary curriculum and priestly formation, and even the promulgation of papal bulls within their domains were often handled by state rather than church. In Catholic Europe these arrangements were often formalized with the Holy See, some more amenably than others. Such governance agreements still exist, the most controversial example being the 2018 Holy See-China agreement. The exact text of that agreement has not been disclosed, but what is known is that it involves the pope selecting Chinese bishops from those recommended by the state and that the pope has authority to veto a bishop China recommends. It was renewed in October of last year for an additional four years.

To its great credit, the American republic has, since its foundation, allowed the Catholic Church to govern herself. American bishops have always been chosen by the pope and those bishops, in union with the pope, have governed the church in America. And it in turn always recognized the legitimacy of the republic. Through the energetic efforts of American clergy and laity, Catholics weathered sporadic and sometimes violent anti-Catholicism and have made amazing contributions to all spheres of American life. The astonishing success and expansion of American Catholicism—its churches, schools, social service institutions, and cultural impact—is in great part due to its independence from but respect for its republican institutions. That respectful independence sets it apart from the experiences of the church in so many other corners of the world, new and old. That is what makes Vance’s criticism of the USCCB so strange. From Ireland, to Spain, to Quebec, close church partnership with state interests has compromised the church’s witness and accelerated secularization.

Vance’s most interesting, well-developed, and honest theological engagement on the immigration issue came not in his disparagement of the USCCB on CBS but in his positive case for immigration restriction made on Fox News in the aftermath of the controversy:

But there’s this old-school [concept] — and I think a very Christian concept, by the way — that you love your family, and then you love your neighbor, and then you love your community, and then you love your fellow citizens in your own country, and then after that you can focus and prioritize the rest of the world. A lot of the far left has completely inverted that. They seem to hate the citizens of their own country and care more about people outside their own borders. That is no way to run a society.

There is insight here and it is a Christian one, although not uniquely so. It is a more general truth of natural law rooted in the nature of the human person irrespective of time, place, or circumstance. It is discernable by human reason irrespective of nation, color, or creed. It is traditionally taught in Christian catechisms as a derivation from the fourth commandment, “Honour thy father and thy mother: that thy days may be long upon the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee.” (Exodus 20:12) As explained in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (2199):

The fourth commandment is addressed expressly to children in their relationship to their father and mother, because this relationship is the most universal. It likewise concerns the ties of kinship between members of the extended family. It requires honor, affection, and gratitude toward elders and ancestors. Finally, it extends to the duties of pupils to teachers, employees to employers, subordinates to leaders, citizens to their country, and to those who administer or govern it.

This commandment includes and presupposes the duties of parents, instructors, teachers, leaders, magistrates, those who govern, all who exercise authority over others or over a community of persons.

Vance is right that we have positive duties to those closest to us and to harbor ill will or feel resentment toward them is wrong. Using this intuition, reasoning, and tradition as the basis for a justification for the immigration policies of the Trump administration is, however, a stretch.

Jesus’ Parable of the Good Samaritan is one of the most beloved. It captures the imagination in part because it complicates this very question. A lawyer asks Jesus what he must do to attain eternal life. Christ answers with another question asking his interlocutor what is written in the law, and the lawyer responds rightly: “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy strength, and with all thy mind; and thy neighbor as thyself” (Luke 10:27). The lawyer then, seeking to justify himself, asks, “Who is my neighbor?” In the stilted language of the theological controversy Vice President Vance opened, “Who is in my responsibility in the ordo amoris (order of love)?” Christ answers:

A certain man went down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell among thieves, which stripped him of his raiment, and wounded him, and departed, leaving him half dead. And by chance there came down a certain priest that way: and when he saw him, he passed by on the other side. And likewise a Levite, when he was at the place, came and looked on him, and passed by on the other side. But a certain Samaritan, as he journeyed, came where he was: and when he saw him, he had compassion on him, and went to him, and bound up his wounds, pouring in oil and wine, and set him on his own beast, and brought him to an inn, and took care of him. And on the morrow when he departed, he took out two pence, and gave them to the host, and said unto him, Take care of him; and whatsoever thou spendest more, when I come again, I will repay thee. Which now of these three, thinkest thou, was neighbour unto him that fell among the thieves? And he said, He that shewed mercy on him. Then said Jesus unto him, Go, and do thou likewise. (Luke 30:37)

The parable, like all of Christ’s parables, is unfathomably rich. It does not provide an answer conditioned by nation, religion, or ethnicity. Those boundaries, it transcends. What there is, is physical proximity, recognition, compassion, and action. It doesn’t give us a rigid category of “neighbor” but tells us how to be one wherever the Lord puts us.

The Lord has placed migrants in our midst, and we have duties to them as neighbors. The form and substance those duties take in our communities, churches, and nations are different. There will be differing policy proposals to address immigration put forward by people of good will, but the fourth commandment isn’t an escape clause, it is a call to responsibility.

Patrick T. Brown: Ross Douthat Wants to Make Faith Great Again

New York Times columnist Ross Douthat (whose recent appearance on The Remnant you should listen to) has never shied away from religious themes in his work. But in his new book, Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious, he tackles head-on some of the questions skeptics of religion pose. Patrick T. Brown has a review on our website.

Believe engages with materialism on its own terms. Roughly the first half of the book deals with consciousness and the cosmos, from the start of the universe to the end of life. Science, far from disproving religion, has deepened it. “We have much better evidence for the proposition that the universe was made with human beings in mind…than ancient or medieval peoples ever did,” Douthat argues. Some who presume faith and reason are incompatible may well have their eyes opened.

From there, he guides the reader in how to think about the variety of spiritualities on offer, with an expansive, egalitarian argument for belief over apathy. And it’s this second half that seems more likely to wiggle its way into human hearts than the more abstract first chunk (I trust Mr. Douthat will not take it as a personal offense when I say his better half has a defter touch writing about scientific concepts than he does.)

Without quite fully lapsing into Huxley-esque perennialism—that is, the idea that every religion reflects different facets of a core truth, beneath cultural differences—Douthat argues that belief in anything is preferable to indifference. Even converting to the “wrong” belief system, he suggests, can rescue one from “the mire of meaningless and the snares of indecision.”

But Douthat’s work is at its best when it makes the case for Christianity instead of just the general trappings of religiosity, according to Brown:

A book arguing it is good to go to church or mosque or synagogue, even if you don’t actually believe in the supernatural bits, would have been a trivially easy book for Douthat to write. Asking the reader to grapple with the claim that the spiritual, moral, and ethical claims of religion matter as much as, if not more than, the benefits community and fellowship provide, is a harder task. In a “spiritual but not religious” world, Douthat seems to be channeling C.S. Lewis, who said in 1952: “You can shut [Christ] up for a fool, you can spit at Him and kill Him as a demon; or you can fall at His feet and call Him Lord and God. But let us not come with any patronising nonsense about His being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to.”

The Dispatch Faith Podcast

In the Trump administration’s efforts to dismantle offices like the U.S. Agency for International Development, figures both inside and outside of the administration have lobbed rhetorical volleys toward Christian relief agenccies—with Elon Musk and former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn going so far as to accuse Christian relief agencies of breaking the law. It all raises the question: Is the New Right interested in what old-school conservatives thought of as “compassionate conservatism”? For this week’s Dispatch Faith podcast, I spoke with the aforementioned Patrick T. Brown, a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. We discussed the history (and future) of the principles behind “compassionate conservatism,” Brown’s assessment of where pro-family policy may be going, and his review of Ross Douthat’s book. Give it a listen here.

These weekly conversations with Dispatch Faith contributors are available on our members-only podcast feed, The Skiff.

More Sunday Reads

- A few weeks ago we published a Dispatch Faith essay exploring the Orthodox Jewish movement known as Chabad. In Law & Liberty, David Goldman reviews the forthcoming book Kabbalah and the Rupture of Modernity, written by Elu Rubin, which recounts Chabad’s history and the ways in which it confronts modern science. “Chabad’s bold assertion of religion’s preeminence over science has deep importance for religious outreach. Jews won a fifth of all Nobel Prizes in physics, but not one of the Nobelists was observant as an adult. To flourish, Judaism must persuade its most talented children that a passion for science and a passion for God are mutually reinforcing rather than antagonistic. Ultra-Orthodox Jews often view secular studies with suspicion. Chabad, in Rubin’s account, sees an inspiration for scientific discovery in Kabbalah.” Goldman continues later: “Rubin’s contribution to this literature is especially welcome because it comes from a vibrant Jewish movement rather than a recondite corner of academia. Chabad’s claim that Judaism inspires discovery at the frontier of science may prompt the revival of a realm of Jewish thought that has been neglected in the past two generations. The revival of traditional religion does not imply a repudiation of the beneficial accomplishments of modernity. On the contrary: It may prove an inspiration to scientists who have been wandering through a maze of ontological paradoxes since the advent of quantum theory.”

- The Aga Khan, Karim Al-Hussaini, died Tuesday at age 88. An uber-well-connected philanthropist, he was the leader of a sect of Shia Islam known as Ismaili Islam (and will be succeeded in that role by his son). Le Monde published a great explainer this week, full of interesting information about the obscure Ismaili Islam (and read to the end to see how it may have inspired the storyline of a popular video game). “Ismaili Islam is a branch of Shia Islam. According to the Shiites, temporal and spiritual power is vested in the imams, or those who lead their followers from ‘in front,’ who are appointed from among the descendants of Fatima, daughter of the Prophet Muhammad, and Ali, his son-in-law. The Ismaili branch, for its part, broke away from the other branches of Shia Islam around the year 765. At that time, in Medina, Ja’far al-Sadiq, the sixth imam and a descendant of Ali, designated his son Isma'il as his successor. But Isma’il disappeared before his father’s death … For Ismailis, a follower’s spiritual journey, guided by their teachings and devotion to their Imam, is far more important than the legal prescriptions of Islam, including the five pillars. Many Sunnis have seen this as undermining Islamic law, forcing Ismailis to adopt lives of extreme discretion to avoid persecution. This discretion would become a foundational practice of Ismaili Islam, one that they would retain throughout their history. Indeed, the Ismailis have been considered to be the inventors of the concept of taqiyya, the art of concealing one’s religious practices, a concept that is used today in certain Islamist activities.”

A Good Word

Ryan Keating is a U.S.-born missionary who spent a decade in Turkey planting new churches, endured the brutal murder of three friends who had converted to Christianity, and eventually had to flee to escape government crackdowns. He now brews coffee and makes wine at a cafe in the Mediterranean island of Cyprus, while training his workers and welcoming refugees. Journalist Mindy Belz tells his story for Christianity Today: “Keating discovered that coffee tasting, which he learned as a hobby while teaching and working on his doctorate in Turkey, could become a transferrable skill during years of working as a missionary—first in Turkey, and now in the divided island nation of Cyprus. It led to coffee roasting, to importing and exporting beans, to opening cafés and training others in the business. The coffee trade fed Keating’s interest in winemaking, which led to hosting meals and to organizing events, from art shows and piano concerts to worship services and Bible studies. All the while, what the café really does is crack open ways to connect with the community. For an American in the Middle East, that’s no small achievement. ‘I love the café,’ he says, ‘but I love it because of the way it fuels the other things I do.’” Belz continues: “Keating saw the importance of the divided island nation as more than a transit lounge for displaced people. He prayed for God to make Cyprus ‘a deep well for the blessing of the nations.’ His prayer led to a new understanding about the Asians, Africans, Greeks, Turks, Europeans, and Americans living around him, he says now. It spurred a vision for recruiting young people from Central Asia, Europe, and Africa to train for ministry. The three-month discipleship course in 2023 included young people from Belarus, Germany, Sierra Leone, Uganda, Kyrgyzstan, and California. As he watched students grow, he knew he wanted to cultivate in particular the coffee and wine businesses, ‘things that teach the value of time and investing in a place.’”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.