Have you heard of a group called “F3”? I confess that I hadn’t. At least not until Saturday morning, when I read this outstanding Ruth Graham report in the New York Times. The group’s name is short for “fitness, fellowship, and faith.” The goal is ambitious. John Lambert, the group’s CEO, told Ruth that the aim is nothing less than solving “middle-age male loneliness.”

The concept is simple. Get a group of men together in the “predawn gloom,” get them to push themselves and each other in a series of grueling workouts, and then join in fellowship to talk and sometimes pray. It seems to work. The group was founded in 2011, and there are now 3,400 chapters across the country, and many of its members credit the group with changing their lives.

Ruth’s story communicates a central theme: The workouts are important, but the relationships are transformative. Friendship matters, and here is a place where thousands of men are finding friends.

The more I think about the challenges afflicting America’s men and boys, the less I think about ideology and the more I think about technology. While left and right fight furiously over who’s to blame for the fact that young men are falling behind in school, men are overwhelmingly more likely to die of despair, and men are suffering a crisis of loneliness and friendlessness, we’re neglecting the most mundane and powerful of explanations—the world changed, and men have been struggling to adapt ever since.

Let’s think of the first several millennia of human history. It’s not just that life was punishing and fragile, it was also remarkably physically strenuous. From our comfortable 21st-century viewpoint, it’s hard to imagine the pure physical challenge of premodern existence. From raising crops to building homes to fighting in wars, there was an enormous premium on raw, physical strength.

This physical premium meant that men—by their physical nature—were going to dominate every active physical field of life. They were (with vanishingly few exceptions) going to be the builders, explorers, and soldiers. Moreover, the lack of effective birth control compounded the physical differences. During their physical prime, women were going to be preoccupied with bearing and raising children.

Combine that fact with the reality that U.S. life expectancy was much lower when families were much larger, and you have the recipe for an unalterable formula: a biological reality that dictated gender roles. During their shorter and harder lives, the differences between men and women were amplified and solidified.

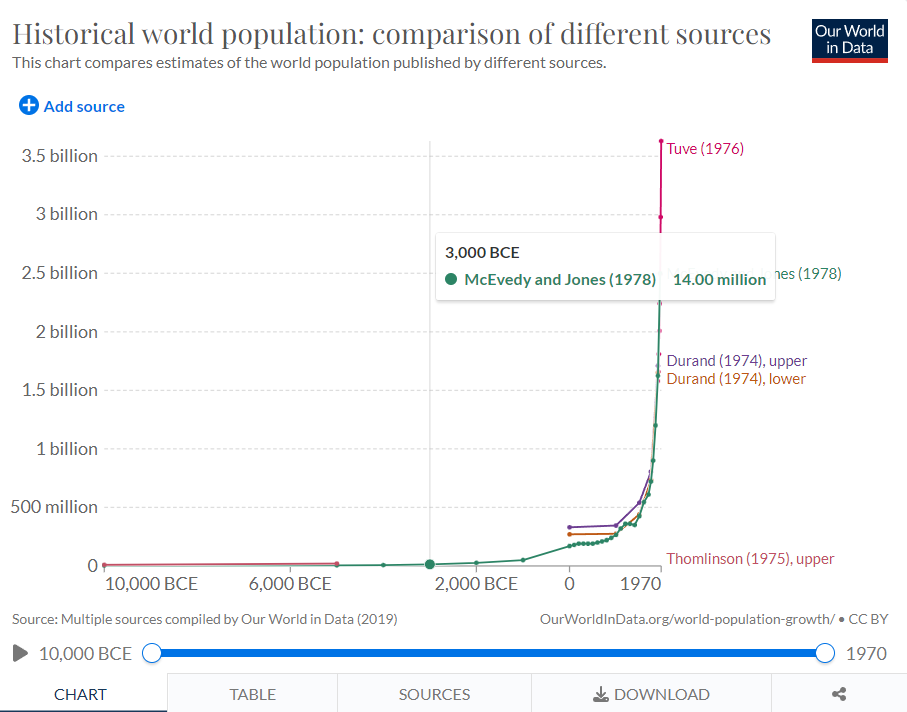

But then came the industrial revolution. Then came the information revolution. In a remarkably short span of time (especially in contrast with the hard, but relatively stable realities of the previous thousands of years), life got easier. The world population exploded:

Automation meant that it was simply easier to live. Birth control meant that parents could regulate the size of their families. And that meant that many of the previous sharp divides between men and women no longer made sense. If physicality became less important than mental acuity—and if women’s lives were no longer dominated by the demands of serial pregnancies—then why would workplaces remain male-dominated?

What was once more natural quickly became unnatural, and the patterns and habits that built up over centuries no longer made innate sense. The old reality could not hold. And to the extent it was propped up by artificial barriers, maintained by discriminatory laws, it should not hold.

Even the most traditional male strongholds transformed. The military became more cerebral and less physical. And while there is still a need for an enormous amount of raw toughness, the much smaller, less infantry-focused U.S. military could cut through the mass-mobilized forces of old like a hot knife through butter.

And have you been in an American factory lately? There is still a need for physical strength in some jobs, but the entire workplace is far, far more accessible to women than any factory at the dawn of the industrial age.

What does all this mean for men? In the times before the combination of the industrial and information revolutions, men didn’t just possess a clear default purpose (builder, protector, and provider), they also had a clear path to forming meaningful friendships. Demanding male work created spaces for rich male relationships.

As men confront this new world, it thus should not surprise us that many are experiencing both a crisis of purpose and a crisis of relationships. In his outstanding new book Of Boys and Men, Brookings Institute senior fellow Richard Reeves documents these immense social and economic changes more effectively than anyone I’ve read, and he does something else truly important—he argues that our ideological wars over masculinity are making everything worse.

Men would have a difficult enough task orienting themselves around new realities, but that task is made even more difficult by ideological combatants who are both galloping to extremes and blaming the other side for the crisis.

Writing about the cultural left, Reeves notes that “It is one thing to point out that there are aspects of masculinity that in an immature or extreme expression can be deeply harmful, quite another to suggest that a naturally occurring trait in boys and men is intrinsically bad.” He argues that the phrase “toxic masculinity” is “counterproductive.” It teaches men and boys that there is “something toxic inside them that needs to be exorcized.”

But the right is riddled with its own problems. If parts of the left are going to label stereotypically “male” characteristics, such as “achievement,” “risk,” “competitiveness,” or “aggression” as harmful, then parts of the right are going to glory in the stereotypes. You see this all over the populist right. There’s an obsession with “manliness,” and manliness is defined far more by physicality and aggression than by courage or wisdom.

Perhaps the apex of these shallow obsessions and definitions came when Ted Cruz and other right-wing personalities praised Russian military propaganda before the Ukraine war. Russian military ads portrayed an Army full of heavily-muscled, stone-cold killers. This alleged dominance didn’t survive first contact with the western-trained Ukrainian military.

If left and right are leading us astray—and if the world has changed irrevocably—what can we do to provide men and boys with a sense of virtuous purpose? I think we find the answer in the arenas where men struggle the most—as husbands, fathers, and friends.

Do we want to know where men are indispensable in American society? Yes, there are still jobs that it takes mainly men to do, but those kinds of careers aren’t the answer to the crisis of masculinity. The answer to the crisis lies much more in distinct, virtuous masculine relationships. Only men can be husbands. Only men can be fathers. And men need male friends.

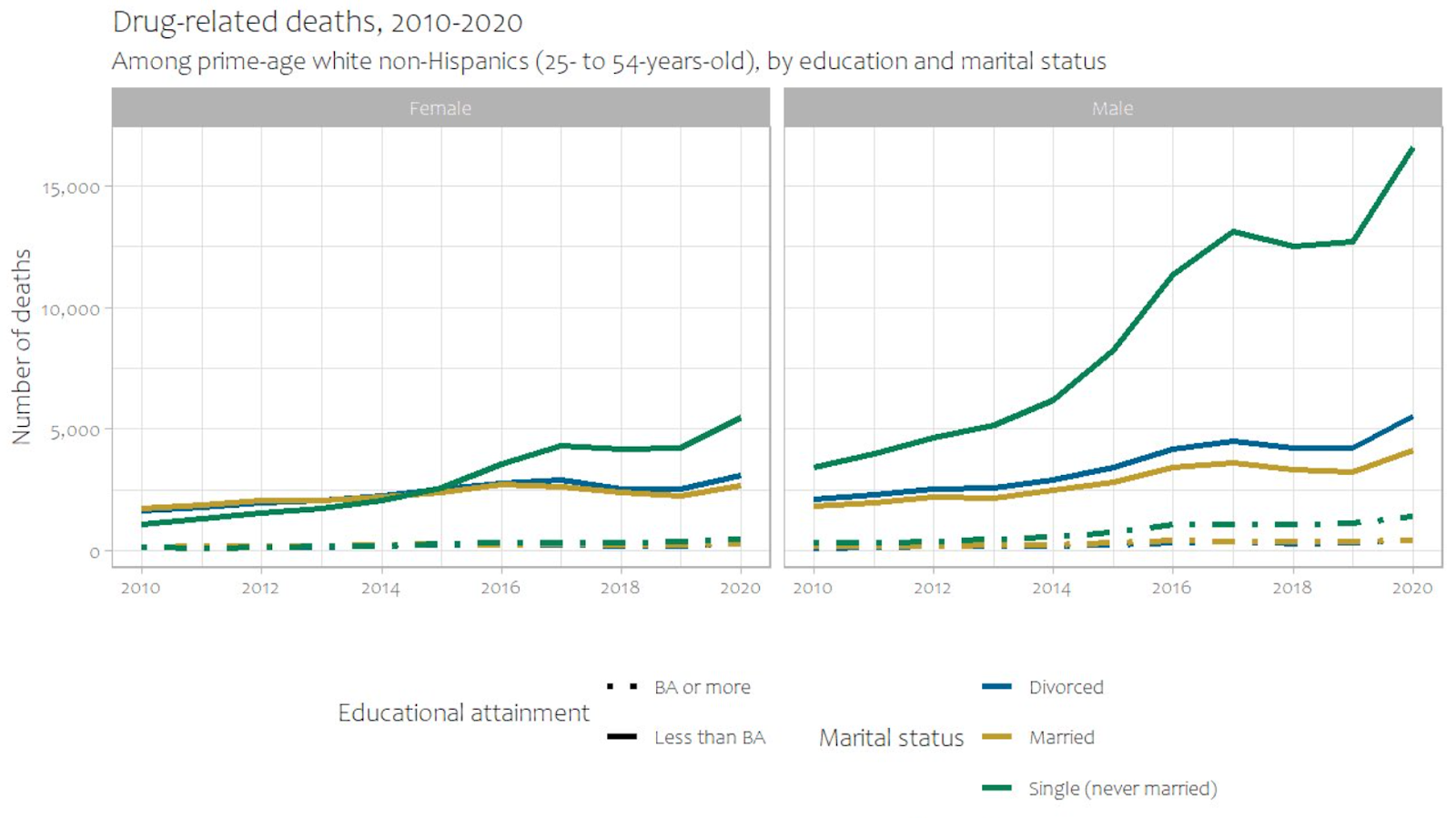

I don’t have the space to fully recount how fatherlessness, singleness, and friendlessness are blasting apart American men, but a few statistics should suffice. At the start of this piece, I noted how single men disproportionately suffer from deaths of despair, but sometimes you have to see a visual to truly understand the depth of the crisis:

As the Ethics and Public Policy Center’s Patrick Brown writes, “[W]e don’t talk enough about the opioid epidemic in general, and we really don’t talk enough about how single and divorced men are the ones bearing the brunt of this scourge.”

Moreover, fathers are so powerful in a young boy’s life that even living around the presence of other fathers can have a positive impact on a boy growing up without a dad. The mere presence of a paternal male role model can change a life.

And what about lost friendships? I’ve written about this before. American friendships are in decline, but men are hardest hit. Almost half of all men report having three close friends or fewer. Between 1990 and 2021, the percentage of men who reported have no close friends quintupled, from three percent to 15 percent. The percentage who reported ten or more close friends shrank from 40 percent to 15 percent.

This Saturday Night Live skit is sad and funny, in part because it’s describing something real:

That which was once more natural now has to become more intentional. Families that once stayed together out of necessity must now stay together out of choice. Male friendships that once formed as the natural result of the proliferation of exclusively male spaces now often require deliberate cultivation.

That’s where groups like F3 can change lives. Not many men will be on a football team, and football teams are fleeting. Not many men will be in an infantry platoon, and that life is temporary as well. But men can still choose to gather together and bond through shared experience and hardship.

Moreover, increasing our cultural emphasis on the male roles of husbands, fathers, and friends also serves the purpose of largely liberating men from the ideological battles over the trappings or stereotypical affectations of masculinity. There are many ways to fill those roles, and the diversity of masculinity can find its home in the diversity of those relationships.

This doesn’t mean men should define themselves entirely by hearth and home. There is great meaning in work, and there are still many professions that require disproportionate numbers of men to meet their physical demands. But it is the presence or absence of those key relationships that is far more critical to a man’s ultimate identity and purpose.

Those relationships are both challenging and attainable. Not everyone can or should get married or have children, of course, but virtually everyone can form friendships. Telling men that true masculinity is found in heroism or adventure or physical strength, by contrast, can lead to a profound sense of loss or emptiness when real life turns out to be far more mundane, and it can trivialize and minimize the immense purpose and value of diligent work and steadfast love.

Let’s end where I began, with Ruth’s portrayal of F3. She painted a beautiful portrait of the power of friendship. She talked to a middle-aged account manager named Glenn Ayala. The group stood by his side when his marriage floundered and when he struggled to connect with his son.

Those are the exact crises that would destroy many men, perhaps even costing them their lives. Yet Mr. Ayala’s friendships hadn’t just sustained him, they’d helped him grow. “I’m not the same person I was when I started,” Ayala told Ruth. “I’m not where I want to be, but I would definitely say I’m a better version of myself.”

Friendship enriched Ayala’s life. It saved him in a time of crisis. Yet I have no doubt that Ayala’s friends were enriched by the relationship as well. There is profound meaning in coming to another person’s aid, and there is real purpose in lifting up a friend in need.

What is the short story of modern men? Life has changed forever. Ideologues pull men and boys into destructive and unsustainable extremes. Yet virtuous purpose can still be found in the fundamental building blocks of the good life. Only a man can be a husband, only a man can be a father, and men need male friends. If a man can fill those roles with integrity and courage, then doubts about his masculinity should not ever darken his heart.

One more thing …

In the most recent Good Faith podcast, Curtis asked—and we try to answer—a fascinating question: Is evil weaker and more brittle than we think? The conversation is inspired by the war in Ukraine, but the answer doesn’t depend on the outcome of that conflict. Evil can be strong, but is it truly as strong as it appears? We say no, but I’d love to read your thoughts. I’ll read as many comments as I can.

One last thing …

In his newsletter this week, my friend Russell Moore reflected on the 25th anniversary of the death of Rich Mullins. Russell and I have many things in common, including the way in which Rich’s songs have stayed with us our entire lives. Here is Russell’s list of top Rich Mullins songs, which I think is largely right:

Here’s a beautiful cover of one of those songs, “Hold Me Jesus,” by Jon and Valerie Guerra:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.