Late last year, the Ronald Reagan Institute commissioned me to write an extended essay about Reagan’s first inaugural address. When I re-immersed myself in the American world of the 1980 election and the 1981 inaugural, I was struck by some powerful similarities to the present.

No, there was no pandemic. No, there had been no uprising at the Capitol. But America was in a state of stagnation and malaise. Americans feared their nation was in a state of terminal decline. If you could mark the course of American history from the Tet Offensive to Reagan’s inaugural, it was a long story of defeat in Vietnam, corruption in the Nixon White House, energy shocks at home, and humiliation at the hands of the Iranian ayatollahs abroad—all against the backdrop of the seemingly-invincible Soviet menace.

In that context, Reagan had two great tasks, one intangible and the other tangible. He had to revive the American spirit, and he had to restore American power. He accomplished both, and he did so convincingly enough that by the end of George H.W. Bush’s term (the culmination of the Reagan era), the United States stood astride the world as its lone superpower, a “hyperpower” without recent historical precedent.

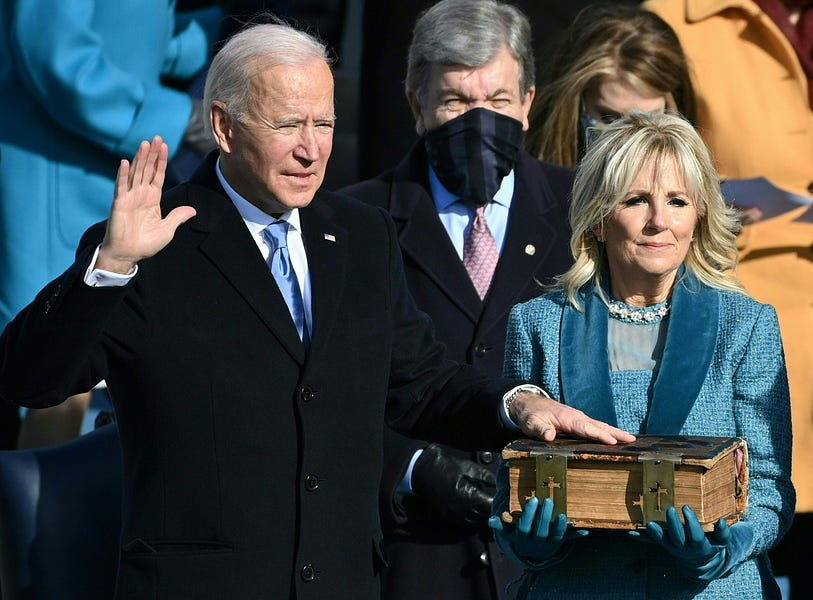

Joe Biden has two great tasks, one intangible and the other tangible. He has to restore a significant measure of American unity, and he has to defeat a deadly virus. Accomplish those goals, and (barring additional unexpected crises) he’ll almost certainly be deemed a success. Fail and, well, brace yourself.

Biden’s intangible challenge is by far his most difficult. He assumes the presidency of a nation divided. It’s arguably more divided than any time since the 1850s. As I chronicle at length in my book and have chronicled time and again in the pages of this newsletter, American polarization isn’t just a matter of differences and disagreements, it’s a matter of fear and loathing.

The conspiracy theories that dominated right-wing media since the election do not spring from healthy communities. The illiberalism that has choked out discourse in influential quarters of the left does not spring from healthy communities. And the violence that tore apart American cities this summer and that played out live and in shocking detail on January 6 comes from a very deep well of grievance and outright hatred.

To even begin to address mutual contempt and loathing, Biden has to relentlessly and clearly distinguish—not just in his rhetoric, but also in his actions—between good-faith disagreement and divisive provocation. I think he put it well in his inaugural:

To all of those who supported our campaign, I am humbled by the faith you have placed in us. To all of those who did not support us, let me say this: Hear me out as we move forward, take a measure of me and my heart. If you still disagree, so be it. That’s democracy, that’s America. The right to dissent peaceably within the guardrails of our Republic is perhaps this nation’s greatest strength. Yet hear me clearly. Disagreement must not lead to disunion, and I pledge this to you: I will be a president for all Americans, all Americans.

Here Biden is laying down an important conceptual marker: He’s declaring that he knows disagreement isn’t a synonym for division. Our Republic was built to accommodate disagreement.

I’m not naïve. I know that it’s far, far easier to welcome dissent in the abstract than it is in the actual heat of American political debate, where overreaction seems to be the only acceptable reaction to any political position. But the aspiration is there, at least, and an aspiration is a start.

The concrete task of combatting the pandemic is likely the easier of Biden’s tasks, involving the application of massive government resources to a defined public problem. But here’s where competence matters. To go back to Reagan, pouring money into the Pentagon didn’t automatically make the military more lethal. Resources could have been siphoned off into unacceptable bureaucratic bloat. Weapons systems still had to work. Strategies and tactics had to be refined.

In Reagan’s inaugural, he didn’t just pledge to limit government, he pledged to make government work. Here’s a forgotten passage for those who think Reagan’s sole focus was on shrinking the government footprint:

Now, so there will be no misunderstanding, it is not my intention to do away with government. It is, rather, to make it work—work with us, not over us; to stand by our side, not ride on our back. Government can and must provide opportunity, not smother it; foster productivity, not stifle it.

Reagan was addressing an American nation that had been afflicted by government failure after government failure. Biden is addressing an American nation that is also groaning under the weight of government incompetence—and not just federal incompetence.

If I were to chisel out a Mount Rushmore of shame in the response to COVID-19, I’d place Andrew Cuomo and Bill de Blasio right alongside the president who lied to the American people about the worst public health disaster since the Spanish Flu. I’d place the countless politicians who imposed punitive policies and then failed to abide by their own guidelines. Models of effective governance do exist, but they are few and far between.

There is a clear way forward, and that’s getting as many vaccinations in as many American arms, as fast as reasonably possible. Sounds easy? No, it’s an immense logistical and persuasive challenge. The logistical challenge is clear, and we’re faltering. Our Morning Dispatch crew has been on the case:

In the five weeks since the U.S. began rolling out COVID-19 vaccines, the biggest issue has not been supply—it’s been getting doses into people’s arms. That dynamic appears to be changing, however, with the federal government’s vaccine stockpile dwindling in recent weeks as states ramp up the pace of their inoculation efforts.

The Washington Post reported on Friday that—despite Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar announcing earlier in the week a shift toward “ship[ping] all of the doses that had been held in physical reserve”—no such reserve exists, and states should not expect to see the dramatic uptick in allocations they were hoping to receive.

I’d urge you to read the entire, troubling report, but even if we overcome the logistics, we can’t ignore the enormous challenge of persuading almost every American to roll up their sleeve and take the shot. This poll is sobering:

Plainly, the challenge of dealing with American division is inextricably linked to the challenge of the pandemic (just as Reagan’s need to revive American power also depended to a great degree on reviving the American spirit.) There is no sensible partisan reason for the vaccine divide. None. It is a product of American dysfunction.

And that brings me to a final, crucial question. How should conservatives like me—people who disagree with any number of proposed Biden policies—respond to this incoming administration? There’s an easy answer. Call balls and strikes. Agree with Biden when he’s right, and disagree and oppose his policies when he’s wrong. That’s a constructive response that we should apply to all presidents, including to presidents of our own party.

But in a moment of profound crisis, there’s also a deeper answer. Recognize the moment. Recognize the inherent necessity of addressing the crisis of division and the crisis of disease. And that means taking a rooting interest in the success of the core aspirations Biden expressed today.

That’s how history will ultimately judge Joe Biden. Did he ease the two great weights on the American people? If he succeeds, we’ll come to read Biden’s inaugural address as I read Reagan’s: as the beginning of a hinge point in history. If he fails, our challenge will be to persevere until we find a different president, one who is finally worthy of the challenge we face.

One more thing …

I was so very impressed with Amanda Gorman, the youngest inaugural poet in American history. You can watch and listen to her poem below. Make sure you don’t miss the moment when she quotes Micah 4:4, the poetic and powerful verse that captures the essence of a peaceful and just nation:

One last thing …

The NFL conference championships are this weekend, and you know what that means? More Tony Romo. I can’t remember the last time I watched a great football game and honestly didn’t know what I enjoyed more, the game itself or the color commentator losing his mind. Romo’s awesome. Catch the fever:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.