Back when I was in college, I had a conversation with a car salesman that helped change my life. My friend had come into some money (he got his real estate license while still in school and had just made his first big sale), so he did the responsible thing and immediately decided to go car shopping.

We piled into my 1985 Chevy Nova and drove to a car dealer. His first target was a brand-new Mazda RX-7, so he picked the most expensive model on the lot and asked the (obviously skeptical) salesperson if we could test-drive it. Reluctantly he gave us the keys, and we took off.

It was a glorious moment, and my friend was sold. He wanted the car, and he wanted it now. He pulled back in, handed the salesman the keys, and said, “I want it.” The salesman took the keys, looked at my friend for a good long while, and said these immortal words:

“Son, there’s a difference between wants and needs. You want this car. You don’t need it. You might want to think more about what you need.”

That’s not a normal thing for a salesman to say to a 20-year-old who’s about to drop way too much cash on a car. But it was wise. My friend paused and pondered. He didn’t buy the car. I paused also and felt bad for egging him on. There is a difference between wants and needs, and while we shouldn’t always forgo our wants, we definitely shouldn’t neglect our needs.

I’ve thought of that conversation many times, most recently when I decided I wanted a new truck with premium off-road capability. I went back and forth on the wants/needs scale and decided that the remote possibility of a zombie apocalypse meant that I did, in fact, need all the off-road capability I could afford. So I bought the truck. That may not have been the right call.

In politics, we confront the want/needs conflict all the time. In democracy we tend, over time, to get what we want. Our nation’s bloated federal government, for example, is the result of generations of accumulated wants made real. Even our dysfunctional Congress is a product of a public that actually seems to want a “parliament of pundits” (to borrow Jonah’s memorable phrase). They often like to see their representatives waging the culture war at the top of their lungs. Americans from both political parties seem to want greater government intervention in the economic and cultural life of the nation, while we need less.

The evidence of the popular desire for more government is everywhere, and the idea that the two parties have fundamentally different ideas of the ideal reach and limits of government power seems antiquated. To be sure, they’d use government power differently, but they’re both in love with the potential of government to shape the economy and—critically—change the culture.

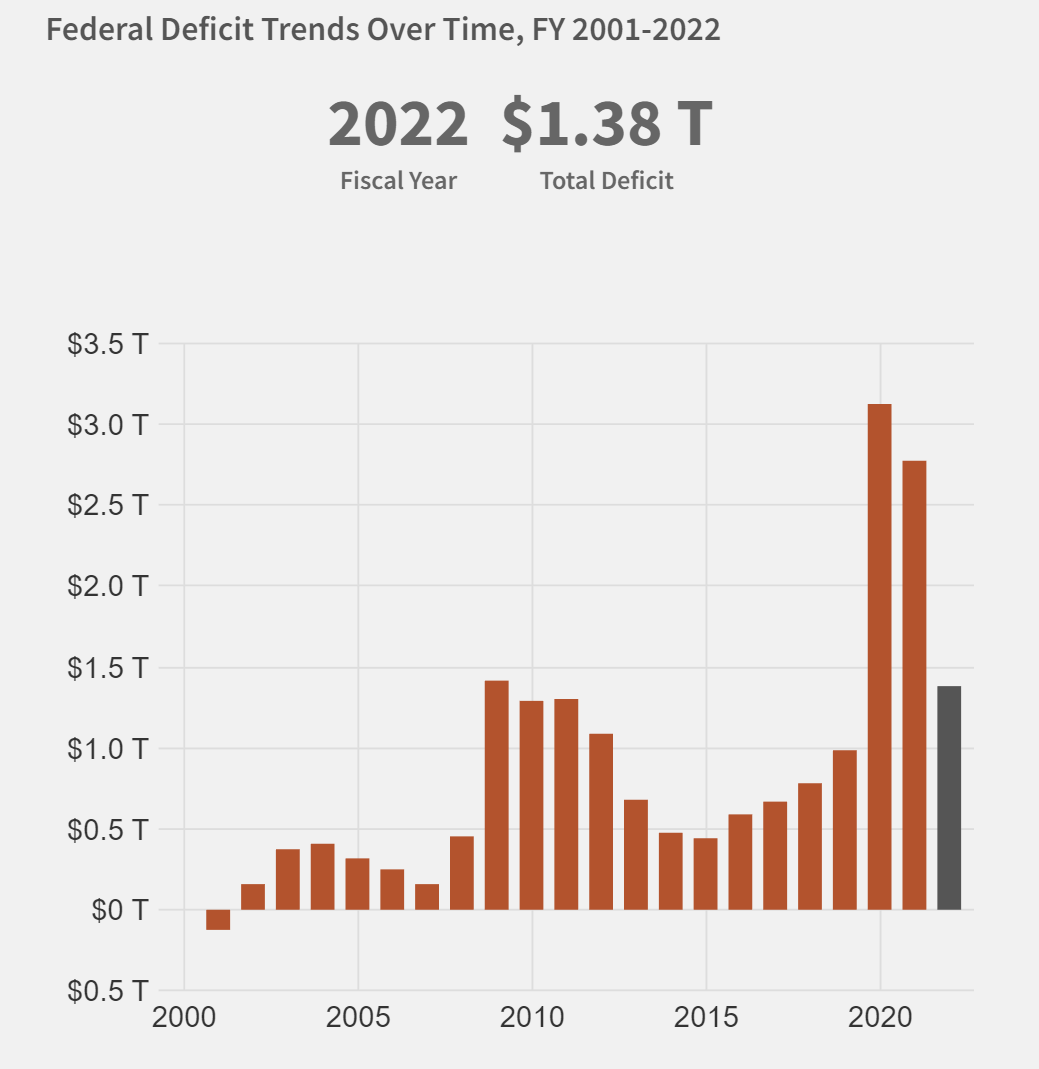

Let’s look at government spending. Take a close look at the Treasury Department chart below. You’ll notice a few trends. First, as a general matter, you see deficits rise during wars and recession and shrink during peace and prosperity. So deficits went up after 9/11 and the Afghanistan and Iraq invasions and then slowly declined until they spiked with the Great Recession.

Deficits declined again during the slow recovery of the Obama years. But then you see the pattern break. Deficits went up every single year of the Trump presidency despite the fact that the American military wasn’t engaged in large-scale combat and the economy continued its recovery. The economy boomed, and the deficit grew.

Fiscal responsibility? Who wanted that?

At the same time, we saw leading Democratic and Republican governors adopt similar views of the power of government over speech and culture. This July I wrote a long piece explaining the shrinking differences between Florida Republicans and California Democrats, at least when it came to their theories of state power.

For example, here’s what I wrote about Ron DeSantis:

Discontent with social media moderation policies, he signed a social media censorship bill that’s been blocked by a federal court of appeals. Angry at corporate and academic wokeness, he signed an expansive “Stop WOKE Act” that limits the free speech rights of private corporations and university professors.

Since I wrote that piece, a federal court has enjoined key provisions of the Stop WOKE Act, blocking provisions that apply to private corporations and to public colleges. But there’s more:

DeSantis has signed legislation that punished Walt Disney for its political speech, placed extraordinarily broad and vague limitations on teaching sexual orientation and gender identity in public schools, and prohibited even private employers from imposing vaccine mandates.

That’s what big-government culture war looks like. Indeed, a key sign of the conservative shift on civil liberties is the embrace of laws purporting to ban critical race theory in red-state legislatures across the land. A focus on restricting speech is a huge flip. Previous red-state legislative efforts focused on protecting free speech on campus, not punishing the expression of ideas that Republicans find offensive.

But if Gavin Newsom vs. DeSantis is our nation’s “inevitable culture war,” as Ross Douthat argued in a compelling New York Times piece this October, then don’t look for Newsom to have a fundamentally different view of state power than DeSantis. California has demonstrated that it is just as happy as Florida to use coercive state power against the state’s political enemies:

California Democrats have launched their own frontal attack on the First Amendment, one that matches or exceeds Gov. DeSantis’s in both intensity and scale. In 2018 the Supreme Court struck down its effort to force pro-life pregnancy centers to advertise for free and low-cost abortions. In 2021 it struck down California’s mandatory donor disclosure laws. It rejected California restrictions on religious free exercise five separate times during the pandemic.

I can go on. California has required churches to provide abortion coverage in their group health plans. It has imposed prohibitions on state-funded or state-sponsored travel to states that possess policies regarding LGBT citizens that it deems discriminatory.

And yet our nation’s spending spree and our political class’s love affair with state power is working out very poorly for our republic. While the most recent inflation reports show improvement, our nation is still suffering under the worst wave of price increases in generations, and it’s hitting families hard. And the weaponization of government in our cultural conflicts fuels many of the most contentious debates of our time.

Last week my friends at More in Common released the results of a yearlong survey of American attitudes about the “history wars”—the conflicts over teaching American history in public schools. The results were both encouraging and discouraging. The encouraging part is easy to state—it turns out that Americans across the political spectrum are broadly united about how to teach history. Our differences are much smaller than we think.

The vast majority of Republicans, notwithstanding the headlines you see, want schools to teach about the ugliest chapters of American history, and they want schools to teach about the distinct histories and experiences of America’s marginalized communities. The vast majority of Democrats want to teach the founding documents as advancing freedom and equality. They do not want to make students feel personally responsible for the sins of the past.

The bad news is that Republicans and Democrats are very wrong about each other. Democrats don’t think Republicans want to teach America’s sins or about the unique histories of oppressed groups. Republicans don’t think Democrats want to teach about the virtues of the founding documents, and they believe that Democrats want students to feel personally responsible for American failures.

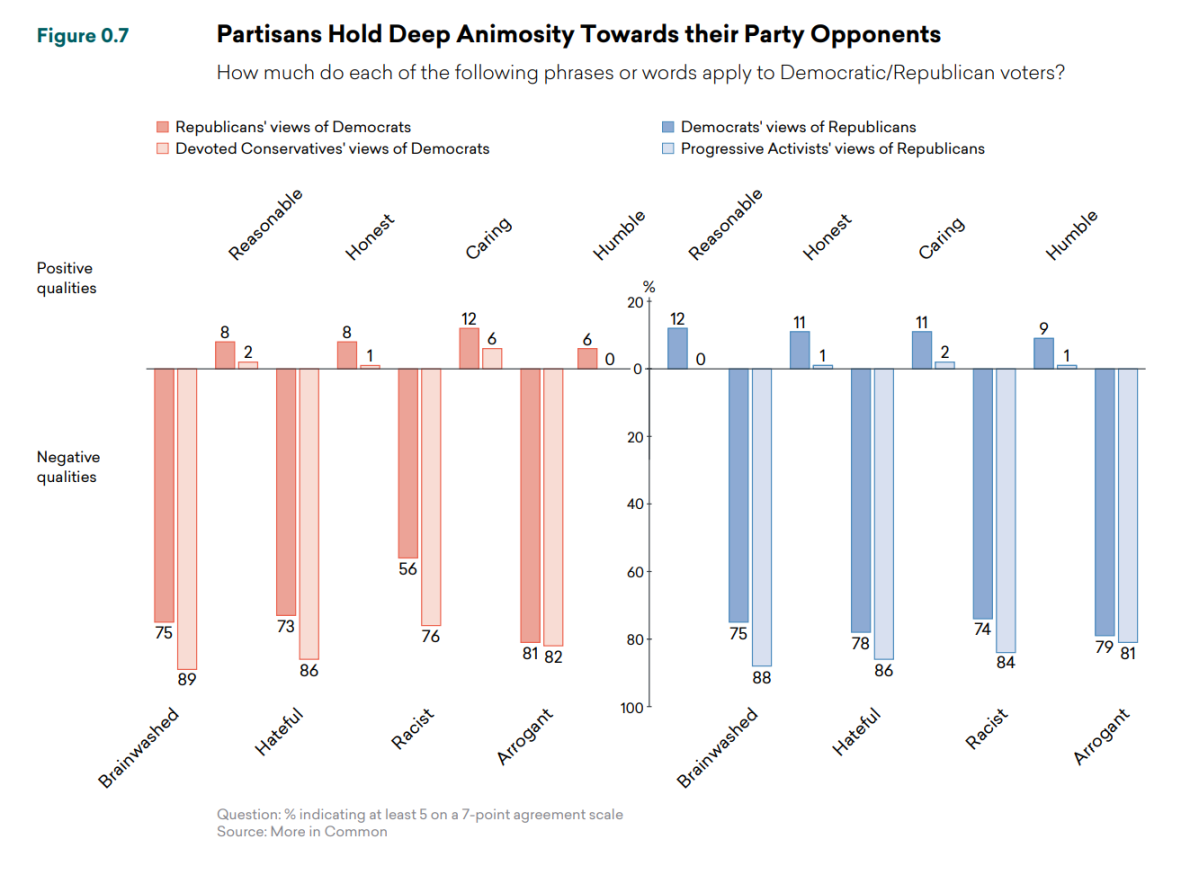

At the same time, More in Common found that Democrats and Republicans really don’t like each other. The data in this chart should concern us all:

These findings mirror the findings in a previous More in Common survey that found American partisans consistently view their political opponents as more extreme than they truly are across a whole host of issues, including controversies related to race, sex, guns, and immigration.

Now let me ask you this—if Americans (especially highly partisan Americans) are in the grips of ignorance and animosity, is this the time to be increasing the role of government in American life? I can certainly see the temptation. After all, if you hate your opponents enough, then one of the key messages of nationalist conservatism—“reward friends and punish enemies”—has a certain inherent appeal.

But I’d argue the opposite. I’ve long been a classically liberal free-market conservative both because of my respect for human dignity (a state that protects liberty preserves human rights) and because of my knowledge of human limitations (people are inherently flawed and can’t be trusted with concentrated power). The animosity of our present age is amplifying our limitations, and as it amplifies our limitations, it decreases my willingness to hand more authority to the state.

As I think back to that car salesman, his words were wise, but his approach was incomplete. He told us about the difference between wants and needs, but he didn’t sell us on our needs. He let us leave without pointing us to something else, something better.

That’s the task of the moment. Liberty, humility, and respect for individual dignity are good products, worth selling. Tens of millions of Americans want the government to do more at the exact moment when we need it to do less, and if we can persuade them to change their wants to match their needs, then perhaps we’ll have a chance to move past this moment of extreme partisan pain.

One last thing …

This Sunday I wrote a long piece arguing that social media companies can learn lessons from centuries of First Amendment jurisprudence and create spaces that both respect free speech and protect users from harassment. Twitter has not struck that balance, and the sheer level of personal vitriol is persuading me to exercise my own freedom and try other social media alternatives. At the invitation of several friends, I created an account at Post, a new social media platform that seems so far to place a premium on civility and decency. It’s still in beta testing, but so far, so good. I’ll keep testing the waters and report back. In the meantime, if you’d like to join me in the experiment, you can check out Post here.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.