Hi,

I just finished recording a very long, very painful, solo podcast about my mom. I can make the case it was a very bad idea. It was hard, meandering, and punctuated by sobs. In one sense it was way too soon. I said my final goodbye on Wednesday. I told some fun stories (I think), but I also wallowed in self-pity over being the last survivor of the world I came from. And my mom was about fun stories, not self-pity.

I can also make the case that it was a good idea. My mom’s health has been such an agonizing part of my life for the last few years, and especially the last 10 months; I wanted to get this chapter behind me. If I waited until next week, I’d spend all week thinking about what to say.

I told Adaam, our producer, to use his judgment about whether to run it at all or about what to cut if necessary. I told him if he’s unsure what to do, to ask Steve Hayes, because I can’t be the final judge. I’m just too close to it all. Heck, close is the wrong word because “close” still suggests distance of some kind, and there is no distance here. As they used to say in the old Palmolive ads, I’m soaking in it.

Similarly, I felt that if I didn’t write this G-File about her, I’d have to do it next week. And I’d rather wing it now than agonize about it all weekend. I certainly couldn’t write about something else; that would be weird for all sorts of reasons. This “news”letter has always been about what’s on my mind and it would be a strange insult to her, to you, and to me, to pretend I had anything else on my mind.

I have no doubt that many readers, never mind friends, fans, and foes of my mom will come down on different sides of the good idea-bad idea divide. And that’s fine.

I bring all of this up not as throat-clearing but to make a broader point. Life—and death—are messy things. It’s Rorschach and Rashomon all the way down and from every angle.

My friend Christopher Buckley got some grief when he wrote his memoir, Losing Mum and Pup. “Pup,” of course, was William F. Buckley. And Chris, his critics charged, was too honest about some unflattering aspects of both his parents. Chris’ response was “your icon, my dad.”

I was going to write that I take no sides in all of that. But the truth is I take all sides in all of that. What I mean is I think everyone is right on their own terms. Chris wrote what he needed to write and Bill’s (and Pat’s) fans didn’t need to read it. Or maybe some did and some didn’t. It’s all messy.

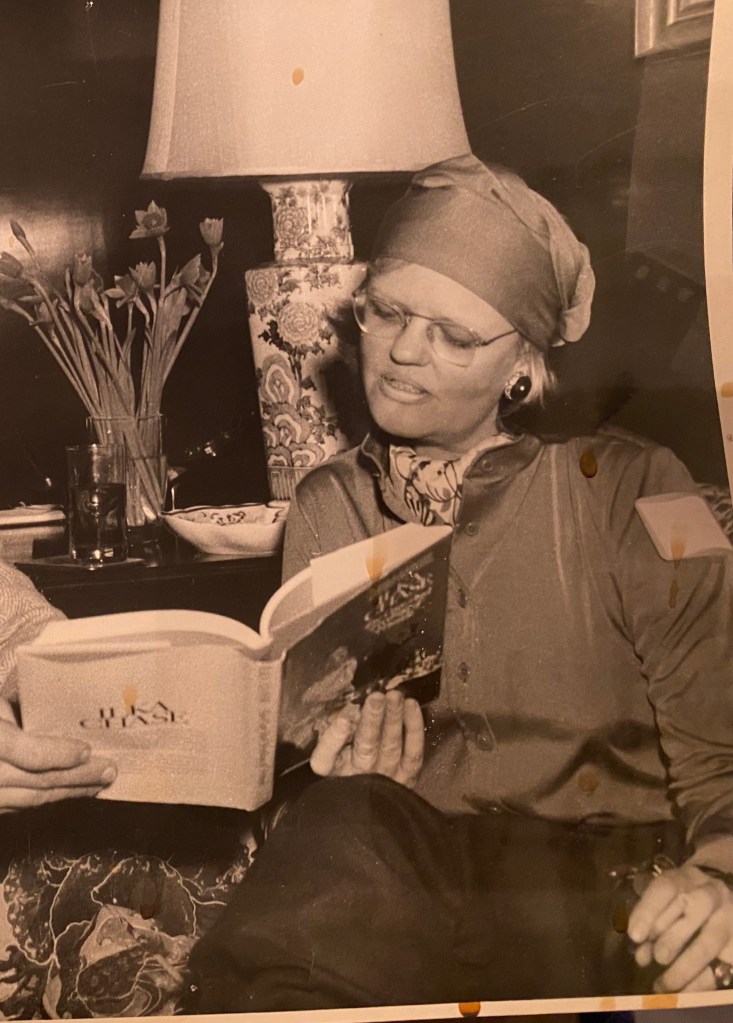

I don’t need to say anything unflattering about my mom. She was an awesome mom. Not perfect. But awesome. I’ve heard from so many people who knew her, and the phrases “force of nature,” “legend,” “unique,” “one of a kind,” and “hilarious,” keep popping up. I’m not going to argue with any of that. Because it’s all true as far as I am concerned. If you want a sense of what the “public” Lucianne Goldberg was like, you should read my dear friend John Podhoretz’s tribute. Or this classic profile by the inestimable Andy Ferguson from 1998 (my mom had that article framed). My mom owned the room when she talked—at a cocktail party, on the phone, or on TV.

When she threw a dinner party, she’d joke about making “Chicken Harold Stassen”—named after the nine-time presidential candidate. “So bad you can’t keep it down.” According to legend, she was fired from the Johnson White House’s press office when she joked with the wrong person, “How do you tell [LBJ’s daughters] Lynda and Luci apart? Lynda is the tall ugly one and Luci is the short ugly one.”

She co-founded an “anti-women’s liberation” group called the Pussycat League. I barely understood what that had been all about, except that we had copies of her book Purr, Baby, Purr lying around and she’d say that it was part of a “bit of fun” she had with friends. I unearthed an old Reuters article from 1972 reporting on the Pussycat League’s first annual “Sourpuss Awards.” They gave one to Carl Friedan, ex-husband of National Organization for Women founder Betty Friedan, for “providing moral and financial support to his wife while she wrote The Feminine Mystique” in which Carl’s wife had written that “any woman who accepts moral and financial support from a man is a prostitute.”

My mom told Reuters, “Women’s lib has done to femininity what the Boston Strangler did for door-to-door selling.”

But the mom I knew was the one who cooked my favorite meals when I was sad and who beat up—verbally and at least once physically—people who threatened me. She was the one who smacked me—only once—when I was a teenager who needed a smack and who’d yell at me, “Jonah, use your good Jewish brains” when I did stupid things. And the Lucianne Goldberg I knew was the one who, when I was a little kid, would take out a book on dog breeds and sit with me as we discussed which dogs we’d like to invite to our imaginary doggy party for our dog Sophie.

When I was little, before she became a very successful literary agent and, later, a novelist, she signed up to be a mounted policewoman for the NYPD auxiliary. It wasn’t so much so she could fight crime—they didn’t even give her a gun—but because she thought it would be fun and make for a good story. She did fend off some kids trying to graffiti the statue of Balto in Central Park. She also gave my brother and me rides on her horse one day when my dad took us to the zoo.

My mom’s fights with “women’s lib” always struck me as strange, because she was in so many ways the most liberated woman I ever knew. It took me years to understand that, for her, she didn’t need a political movement or ideological crusade to define what it meant to be a woman, wife, or mother. It wasn’t until I went to college and got into my own arguments with feminists (I went to an all-women’s college after all), that I fully appreciated where she was coming from. She gave me a kind of psychological immunity to a lot of feminist hectoring about sexism because literally the toughest, most confident, person I knew was my mom. She may have been trolling when she’d say on the lecture circuit in the Pussycat League days that “equality is a step down” but when it came to the woman I knew, it rang true. She wanted a career—and had several!—but she also wanted to be a mom and a wife.

I’m not trying to pick fights with self-described feminists or anti-feminists, I’m just illustrating that reality for me was more complicated than the ideological categories people tried to impose on it.

When I watch old movies, I see my mom in the tough women who clawed out their own identities in a “man’s world” because that’s exactly what she did. And like those older archetypes there was a lot that she liked about that “man’s world,” she just didn’t think it should necessarily apply to her. To use older, now impermissible terms, she was a “tough broad.” She was a mix of Auntie Mame played by Lucille Ball and the real tough-as-nails Lucille Ball behind the scenes.

When my mom had to go to Sardi’s to interview George Peppard for a profile, she brought my then-infant brother Josh in a bassinet. She went to the coat check and gave them her coat and her baby. The coat check ladies loved it. Mom had martinis with Peppard.

She told my daughter recently about how she was the one who tore down the “no women allowed at the bar” rules at the old National Press Club. She didn’t do it in the name of feminism, she did it because she and some male friends wanted to get a drink and dared anyone to stop her. Apparently—this is where the story gets murky—Betty Friedan was nearby and took credit.

I hadn’t heard the story before—or, if I had, I’d forgotten it—and for all I know it was more complicated than that. My mom had all sorts of stories about events and people she knew and things she did, and sometimes the telling of the story was more important than the details. But it completely gibed with the mom I knew. When smoking became frowned upon in New York, my mom would simply bring an ashtray in her purse, put it on the table and dare people to make her stop. This sort of thing could be embarrassing for me, but it was mom.

When I was 6 or 7, my mom ran out of cigarettes (she smoked Larks). She gave me a $20 bill and sent me downstairs to the headshop to buy her a carton. The lady working there said she couldn’t sell me cigarettes. This seemed reasonable to me, and I went upstairs and said they wouldn’t sell to me. My mom put on a coat, and dragged me back to the store and told the lady, “This is my son, you can sell him as many Lark cigarettes as he wants. If he asks for any other brand, you let me know.” Again, embarrassing. Again, mom.

When I think back on it, the strangest thing about my mom wasn’t her politics, her tribal loyalties, or her category-busting feminist anti-feminism that castigated women who said women “can do it all” even as she succeeded as much as anybody I’ve ever known at actually doing it all. It was that she married and loved my dad as much as she did.

Don’t get me wrong. My dad was a catch. But he wasn’t the kind of man you’d think my mom would be fishing for. He was intellectual, quiet, shy, Jewish, and profoundly circumspect. My mom was incredibly smart, but she wasn’t what you would call an intellectual. And she certainly wasn’t quiet, shy, Jewish, or circumspect.

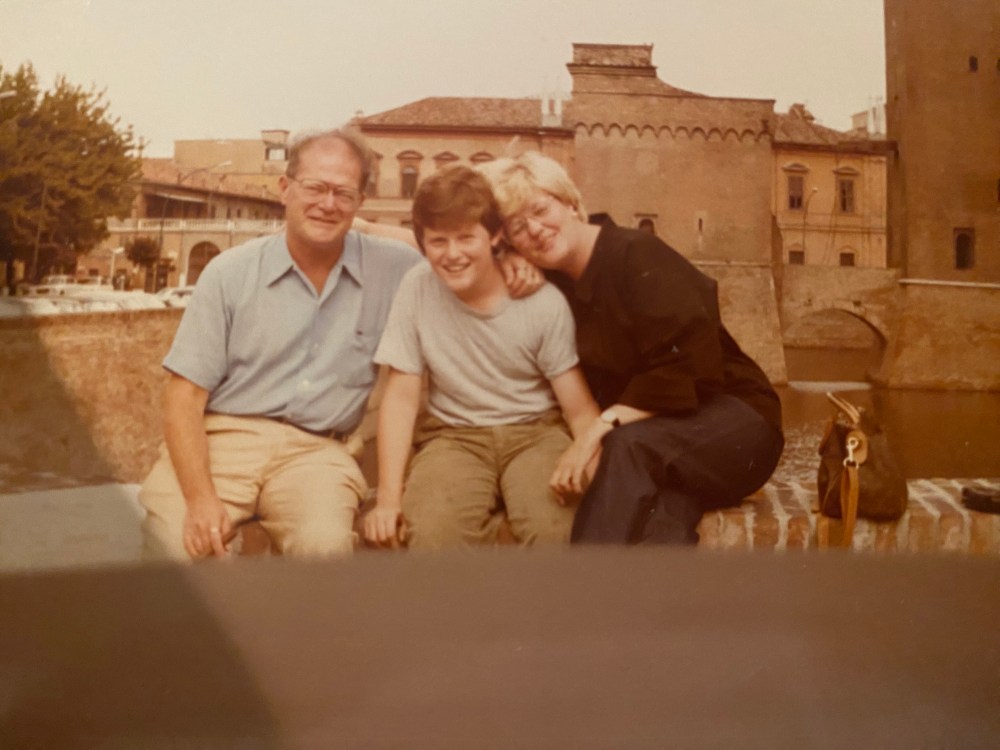

If you’ll forgive even more self-indulgence, I’ll quote the story I told in my eulogy to my dad:

My Dad, already in his late 30s and a respected editor, took Mom on a daytime trip to the zoo. Now, for a gal like Mom, this wasn’t exactly her idea of an exciting date. But she was intrigued. He brought her straight away to the old birdhouse, which hasn’t been there for decades. At the main birdcage he told her to look off to one side where an un-presupposing small bird was standing alone. It took my Mom a few moments to find it. Keep your eye on that one, Dad told her, as she was still wondering what this was all about. And she waited. And waited. What was the deal?

And then, suddenly, the bird hopped.

It was a humble hop, all things considered, but a distinctly purposeful one. And, then nothing. Another longish wait. And then: another hop. And that was it. That’s all it did: Hop, after long intervals and for no apparent reason. It was, as we Goldbergs have called it ever since, “the hop bird.” And my Mom thought it was hilarious. She laughed and laughed and laughed. She still laughs about it today.

If you didn’t have it pointed out to you, you might never have noticed the hop bird. He didn’t look particularly special. He didn’t have showy feathers or huge wings, like many of the other birds in the cage. But he had this hop. And he hopped as he saw fit, on his own schedule, to his own inner clock and, while he surely noticed the other birds, he was content to be unlike them. He was, simply, the hop bird. There was no explaining him. Either you got him, or you didn’t. And if you got him, you loved him.

And my Mom got him.

My dad was the hop bird to my mom’s peacock. He was my mom’s ballast and her biggest fan. He was her editor and her promoter. Of course, they had their fights—both personal and professional (long stories could be told on both scores). Heck my mom was a JFK liberal until, in my dad’s words, he “went to work on her.” But they entertained each other. They were a team, with different roles and strengths to be sure, but they united on a few important things, starting with their two sons. They enjoyed the world outside our apartment on 84th street—in a weird way they were both more social than I am—but the world that mattered most to them was the microcosm in apartment 6A.

Now, that may not seem true to many people who knew my mom. And, in some important ways it might not be true. She was, after all, a very ambitious and sociable woman and life is complicated. But she was the kind of mom who made it seem true to me. And, at the end of the day, that’s all parents can do—make their kids feel like they come first. That’s what my mom did for me. And beneath all of my heartache and self-pity, there’s a granite bedrock of gratitude to her for that.

She was an awesome mom—and she never let me think she wanted any accolade more than that one.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.