Dear Reader (including all of you “influencers” doing Instagram posts for Michael Bloomberg),

Last month around this time I wrote, “Someone please help, I’m trapped in here—and this thing looks like it’s waking up, and might be hungry!” But that’s a story for another day.

Around the same time, I wrote a “news”letter in which I was harsh on Elizabeth Warren. Not unduly harsh, I would say, but duly harsh.

I won’t recycle it all here. But the gist was Warren is an embarrassing fraud. I likened her to Michael Scott from The Office because they both share an inability to recognize they’re debasing themselves. The difference of course is that Michael Scott was a TV character played for comedic effect. In other words, only one of them was funny.

It’s the difference between watching Sean Spicer on Dancing with the Stars—embarrassing in a funny way—and watching Sean Spicer beg his Twitter followers to vote for him to stay on the show literally for Christ’s sake and to show up Godless Hollywood. In other words: Haha vs. Eww.

Warren’s campaign has fizzled, like an oil drum fire on skid row during a steady rain. She’s now like a hobo desperately tearing up the old newspaper she used to make her dumpster-dive shoes fit, in the vain hope the dying embers can be reignited. But that kindling is not only too damp, it stinks.

The woman who mocked and belittled other candidates for thinking too small and not being willing to promise literally impossible things is now asking Democrats to make her the “unity candidate.” Whereas once she was a vessel for “big things,” castigating those who allowed reality to have a say in their programs and desperately trying to win the support of Sanders voters, she now wants to be the candidate who stops the bickering.

“The question for us, Democrats, is whether it will be a long, bitter rehash of the same old divides in our party, or whether we can find another way,” she said Tuesday night after coming in fourth in New Hampshire.

If you want to avoid “another one of those long primary fights that lasts for months,” she said, well, vote for me!

The most obvious and superficial problem with this argument is that any candidate could make it. The factional fights would also end if everybody rallied to one of the 4Bs: Bernie, Buttigieg, Bloomberg, or Biden. Indeed, the internal logic of the pitch better fits Amy Klobuchar because she can make the case that she’d be a less divisive candidate in the contest that really matters: the general election.

And Bernie Sanders—I would argue ludicrously—has been making precisely this argument all along. Everything he wants to do is predicated on a “mass grassroots movement” that unites the Forces of Light against the Forces of No Goodness, Very Badness. We’re going to conquer climate change by marshaling a mass grassroots movement. We’re gonna round up the billionaires thanks to a mass grassroots movement. It’s like mass grassroots movements are both a floor wax and a dessert topping. At his age, he might even appreciate that grassroots are a good source of fiber and a mass of grassroots might deliver an excellent movement of another sort.

But all this misses the more relevant point about Warren. She may truly believe all that she says about wealth taxes, eliminating the Electoral College, confiscating guns, banning fracking, etc., but the thing she really believes in the most is her. This should not shock anyone. After all, a woman willing to pretend to be a Native American to get a job at Harvard Law School and who caters her accent to her audience shouldn’t have much of a problem pretending to be a Democratic centrist.

The dilemma for her is people have to believe it. Bill Clinton had a record as a Democratic centrist—on issues like the death penalty and welfare reform. There’s nothing in Warren’s record as a politician that suggests that she’s anything more than a vessel for woke wishcasting. (Though it is worth recalling that before she ran for office, she was a moderate Republican with moderate views on various issues.) Elizabeth Warren doesn’t want to unite the factions around a policy program or even political triangulation. She wants to unite the factions around her, because at the end of the day, that’s what really matters. And, unfortunately for her, she is not enough.

The mess they’re in.

In my column today, I write about how the Democrats are becoming the ideological party while the Republicans are becoming a coalitional party. Coalitional parties argue over stuff—jobs, money, policies, pork, etc.—while ideological parties argue about ideas because they don’t have any stuff to give away. The problem for the Democrats is twofold: They don’t see the transformation taking place and they don’t have much practice framing arguments in this way.

Barack Obama’s success at getting elected without running to the center in the general election in 2008 sent a false signal—that the long-prophesied “coalition of the ascendant” had finally arrived. Obama showed that all you have to do is fire up the base of minorities, (liberal) women, and young people and you don’t need to compromise with The Enemy anymore.

Obama’s failure to actually deliver on the grandiosity of this prophecy and his own rhetoric left a bitter taste in the mouths of many Democrats. The way the Democrats—minus Biden—have talked about the Obama years has been saturated with remorse about squandered opportunities. But, as I wrote earlier this week, because Democrats can’t figure out why Hillary Clinton lost in 2016, they don’t have a unifying theory about how to win in 2020 suited to political reality. So they’re re-running the Obama playbook. The thing is Obama, the first African-American president, was a unique candidate capable of inspiring voters in ways this crop can’t. You can’t just run as that kind of candidate, you have to be that kind of candidate.

Republicans have decades of practice being a minority party. The conservative movement was deeply shaped by being outside the political consensus. Democrats have no such institutional memory. The closest they come is the example of Bill Clinton, which is why James Carville is losing his mind (in very entertaining fashion) these days. If the left understood its predicament, they would follow a left-wing version of the so-called “Buckley Rule”: vote for the most leftward candidate who’s most electable. Biden tried that, but couldn’t pull it off because he’s a spent force. And, if Klobuchar doesn’t make it then, Biden’s lasting legacy will be that he crowded out the candidates might have sold that pitch until it was too late for anyone else to do it successfully.

The politics of “shut up.”

It should come as no surprise to people familiar with my views that I am not a big fan of “mass grassroots movements.” No, I don’t think they’re all equal. But I am philosophically, psychologically, and politically distrustful of crowds, mobs, rallies, and populist passion generally.

So when I hear people like Sanders insist that everything can be solved by mobilizing a vast mob of angry—or hopeful!—people, it makes me want to buy gold and flip the safeties on my rifles (figuratively speaking).

Part of the problem is that I simply detest the idea that the group with the most people is right. A million people can say that 2+2 = 17 and it is no more correct than if only one drooling idiot says it. But a million people saying it is far more dangerous because a million idiots aren’t just wrong, they’re a constituency. And constituencies attract politicians the way Paul Krugman’s columns attract flies.

When I make arguments like this, someone invariably says, “Oh so you don’t like democracy!”

Well, I don’t love democracy, but I like it just fine compared with the alternatives. But you know what I like more: the Bill of Rights. The Bill of Rights is not a particularly democratic document. The whole point of having one is to take certain things—inalienable rights—out of the hands of the voters and the politicians who pander to them. Sure, voters can change it, but doing so is very, very hard—which is the way I like it.

The Founders understood that democracy could be tyrannical, too. That’s why they set up a system that diluted the ability of popular passions to swamp the government. Disagreeing with this basic principle always struck me as a form of power worship. Usually, people only pound the table and say things like “the will of the people is being thwarted!” when it’s their constituency or faction being thwarted. The moment the system provides a check on the will of voters when the voters are wrong, the same people celebrate the delicate constitutional system of checks and balances and constitutional rights.

If Bernie Sanders won with a populist landslide and immediately used his alleged mandate to confiscate guns or the wealth of the 1percent, without so much as a by-your-leave from the Supreme Court, his fans would cheer democracy in action while opponents would decry mob rule. But if Donald Trump were re-elected in a landslide and set about to rescind the broadcast licenses of the “fake news” those Bernie’s fans would cry “dictatorship” and at least some Trump supporters would hail “democracy in action!”

Well, it’s all dictatorship, people. It’s all mob rule.

This is what I despise about Sanders’s rhetoric. Tinged with a certain amount of Marxist dogma about activating the class consciousness of the proletariat, he makes it sound like merely winning one election is all you need to roll over all obstacles to your agenda. Though, to his credit, and unlike Warren, he at least says he would oppose abolishing the legislative filibuster in the senate. But one wonders how long that position would last.

Sanders says over and over that he is leading a “political revolution.” But winning a single presidential election, in our system, is not supposed to be enough for a political revolution.

Sanders subscribes to the Obama theory of running a base election to force change. That’s fine. But he—and many of the other contenders—go on to say that winning the election would amount to “unifying” the country.

I will go to my grave wondering why people who profess to support democracy want to unify the country. In a democracy, the country is not supposed to be unified, at least not about very much. Democracy in our republic is supposed to be about debate and disagreement. Sanders says that there can be no such thing as a pro-life Democrat. Sanders also says that if Democrats take over, they get to do whatever they want by virtue of the moral power of their “grassroots movement.” So does this mean there can be no such thing as a pro-life American? Whether he does or doesn’t, the fact remains, the country cannot be unified. All you can do is get a government in Washington that says principle disagreement has no place in the realm of policy.

The same thing applies to virtually every public policy you can think of. The country cannot be unified because we are a free people with the right to disagree and the right to make our disagreement known at the ballot box and in the halls of Congress.

When I hear politicians insist they can unify the country, I hear politicians promising one constituency that they can make another constituency shut up.

In a proper democracy, the best you can hope for is consensus—temporary and partial consensus—on a specific issue at a specific time. Unity is about force—strength in numbers—consensus is about persuasion. It comes from the Latin for “agreement” and shares meaning with “consent.” Consent can be forced, but forced consensus is not admirable or desirable in a democracy.

But we live in an age where the constituencies politicians care about most are those that don’t want consensus. They want to make them shut up.

Various & Sundry

Canine update: So first an apology. There was a technical glitch last week and the links to videos in the Canine Update didn’t get published. I am very sorry for the riots and fires that spread throughout most major cities in response to this outrage. The doggers are doing okay. Pippa’s limp is manageable, but I think a visit with orthopedist is inevitable. Zoë meanwhile cut her paw the other day and it seemed scary at first. She limped like she was trying to avoid the draft. I’m sure it hurt, but the vet didn’t even put a bandage on it. We’re keeping it clean, but it pretty much vanishes when she goes outside. The problem remains that restricted duty for them just causes them to unleash their mischief batteries with each other. They’re fine being pampered like sick ward patients at night. But they have expectations about a certain amount of zoominess outside. Gracie is doing important work, too, though.

ICYMI

Last week’s G-file

Democrats can’t agree on 2016, let alone 2020

The weeks first Remnant, with China-watcher Derek Scissors (second Remnant forthcoming)

Second half of my conversation with Bridget Phetasy

My previously mentioned column about Democrats getting more ideological

And now, the weird stuff

Commander Riker thinks you’re wrong Beyond Belief

Fictional buildings and their “real” size

Imagine how much joy this has spread

Digitizing centuries-old literature

Hero dog saves future murder-bear

Art critic mocks sculpture; sculpture immediately one-ups her

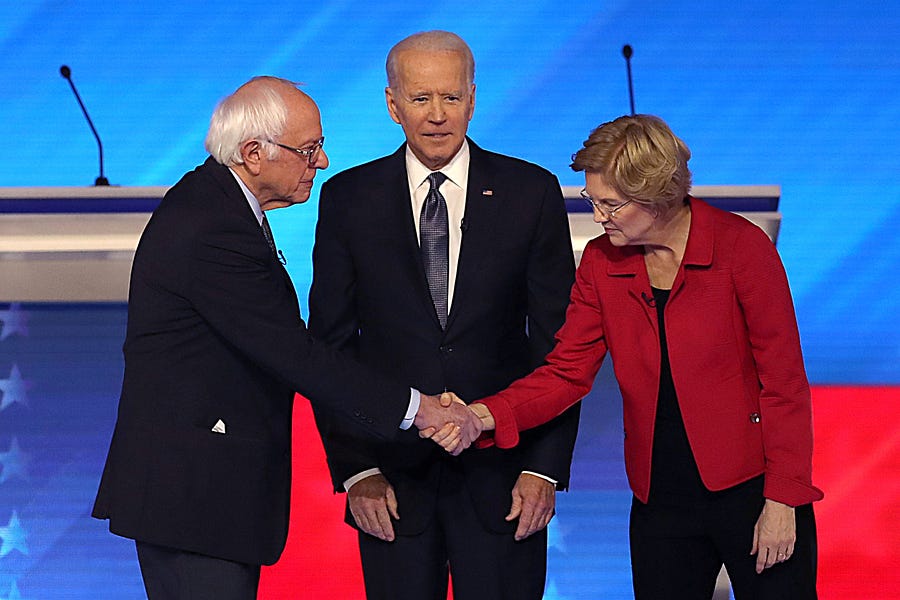

Photograph from the Democratic debate in New Hampshire by John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe via Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.