Dear Reader (especially those of you under pressure),

Let’s pretend Festivus came early this year. By which I mean, I’m going to begin by airing a grievance.

The “parking spots available” sign at Reagan National Airport is a tool of Xezbeth, Belial, or one of the other ancient demons of deception. I once read that in an astounding number of elevators, the “close door” button does nothing. Also, in many cities, the “press to walk” button is just a sop to the human desire for agency and control, but actually does nothing. This enrages me, but nowhere near as much as the “spots available” sign, which seems to just generate random numbers to get people to drive through the garage like a mouse following up on a rumor about cheese at the end of the maze. I imagine that Xezbeth, Belial, and the gang are at the foot of Lucifer’s throne laughing their asses off as I drive in desperate pursuit of these utterly fictional parking spaces.

Of course, I’m joking. Not about the Perfidy of the Parking Sign, but about the demon thing. Yet, a lot of people these days aren’t joking when they talk about demonic forces at work in America. Tucker Carlson recently revealed that he was attacked by a demon in his sleep. His bookshelf has a book on casting out demons. Eric Metaxas talks about demons all the time. And many people sincerely believe that Trump critics are possessed by demons.

We talk a lot about “demonization” in our politics these days, but most of the time people mean it figuratively and analytically—not, you know, literally.

What got me thinking about this was a video tweeted out by Benny Johnson defending the market chaos as an effort to “cast out” the demons controlling America. Now if you watch the clip, it’s reasonable to assume he’s speaking figuratively. But I don’t know why he should get the benefit of doubt since he calls people literal demons all the time.

One of the problems with demonization, in the political science-y sense, is that it gives the demonizers permission to ignore not just the humanity of political opponents but any arguments they might offer. You say the bond markets are tanking and that is bad. The Benny Johnsons get to say, “Not today, Satan. I’m not listening!”

I’m not going to get into the debate over whether demons are real. My only point is that reason and facts have no purchase on the intellect once you accept that your opponents are demons or operating on the orders of them. Personally, I think it’s a tell that someone’s arguments are weak once they resort to demon talk. Maybe not when someone is floating above their bed and talking about Zuul. But I don’t want a doctor, lawyer, or financial adviser whose first impulse is to attribute problems to demonic forces in their analysis or prescriptions. That’s just me.

The nice thing about demonic possession talk is that it’s honest. It puts its unfalsifiable claims out in the open for people to accept or reject.

There are a lot of other kinds of arguments that amount to the same kind of argument, but they hide the dybbuk in the details with fancy language that sounds more technical, scientific, or just clever. Arguments about “white supremacy,” “patriarchy,” “the deep state,” “globalism,” “the Jooooz,” “the 1 percent,” often operate the exact same way. They point to something “bad” and work backward to build the case that “hidden forces”—whether it’s the Pale Penis People, the deep state, the bagel-snarfers or whomever—have expertly pulled strings from their Star Chambers to make it so. The bad thing—real or alleged—is the proof that evil human will is at work. These evil puppeteers are what you might call secular demons for those who reject explicitly religious talk.

This was Marx’s view of the “Jewish spirit” running through capitalism and Hitler’s view of the “Jewish bacillus” running through both capitalism, communism, and anything else he disliked. And it’s the view of countless antisemites on the left and right today. The human impulse to respond to misfortune, crisis, or mere inconvenience and disappointment by asking “Cui bono?” is sadly wired into us. It’s not always stupid or wrong to ask “who benefits” in a given situation. But it’s conspiratorial madness to ask it in every situation. If, like Marjorie Taylor Greene, you can look out the ravages of a wildfire and think Occam’s razor points to Jews using their weather satellites to make a few shekels, you’re not—let me say this nicely—a particularly reasonable person.

One last point on antisemitism since we’re on the cusp of Passover. I will never stop marveling at how people can look at the history of Jews, starting with the story of Passover itself all the way through the hundreds—thousands?—of pogroms, inquisitions, retail cruelties and wholesale genocide, and conclude “Man, those Jews really run everything.”

The vision of the garden and the gun.

Let’s switch gears. I tried to make a point on the solo Remnant this morning and I don’t think I did a very good job, so I’m going to try again here.

A quick recap: I’ve written a bunch of times about the “English garden.” Here’s how I put it most recently (feel free to skip if you know this stuff by heart by now):

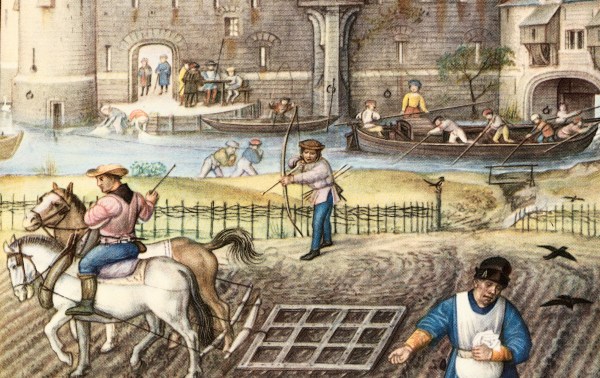

One of my favorite metaphorical illustrations of how to think about the role of the state is the difference between the English and French garden. I wrote about it in my book and here and here. For those who don’t know or remember, the basic idea is that the hyperrationalist French gardens with conic shapes, right angles, and other geometric shapes represent one Enlightenment view of how government should operate, imposing a human vision of nature on nature. The English garden, meanwhile, represents a different model. It establishes a space, free of external threats and invasive weeds, that allows the plants of the garden to grow free into the best versions of themselves.

I find this metaphor to have enormous explanatory power about the differences between two different approaches to politics, but also to economics.

In politics there are people who argue that the state (or movement, cause, faith, etc.) must be salvific. Literally, it is the view that you can deliver the people—all of the people—to some perfect society. The language of this political tradition is all about movement, destinations, marching together, and the like. Nobody is left behind, everyone is included. This is the worldview of all the modern totalitarian movements, and many ancient ones. The problem is that when you try to implement the ideal, i.e. put your idea into practice, lots of people don’t want to go where you’re trying to take them. The totalitarians, or to be more polite, the utopians, get angry at the slackers, wreckers, dissidents, and traitors (whether they’re class traitors, race traitors, or traitors to the nation depends on what your Shangri-La at the end of history looks like). Also, because you’re invincibly confident in the righteousness and rightness of your cause, you assume that any difficulties you run into must be the handiwork of, well, demons—literally or figuratively. So they must be eliminated, cast out, defeated—again, literally or figuratively.

This is where the gun comes in. By the gun, I mean actual guns—or men carrying them—but also force. Government is force. It has a monopoly on legitimate violence. This is one of the points that libertarians have always understood better than any other school of politics. Defy the government about pretty much anything and, eventually, people with guns show up to force either compliance or punishment. Refuse to pay your parking tickets long enough, and eventually the state, armed with guns, will come to collect.

But that’s not really the point I want to emphasize. Government force is more supple, complex, and diverse than just sending in the gendarmerie. The way of the gun can manifest itself with legislation, presidential executive orders, bureaucratic regulations, or even just through the threat of them. There’s a gun somewhere in there, but the point is that government has force, power, and the ability to use it. (Think of it this way. Donald Trump didn’t threaten violence against law firms with his outrageous executive orders. But a gun will enter the picture if one of the target lawyers tries to enter a government building in defiance of it.)

Which brings me to economics. On Monday, Trump acknowledged the pain and turmoil he inflicted on the global economy. Then, he said, “I don’t mind going through it because I see a beautiful picture at the end.” That’s the salvific, French garden approach. I am going to bring all of us to a better place, a promised land.

This way of talking and thinking about politics and economics is hardly unique to Trump. When Barack Obama promised “fundamental transformation” and talked about how, “We are the ones we’ve been waiting for,” he was tapping into the same unconstrained vision. Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, FDR, Woodrow Wilson: They have all thought this way.

For most of my professional life I’ve been beating up on this worldview. The idea that some politicians, surrounded by experts and technocrats, can run or transform the economy, and deliver all of us to a better place through the application of will, intellect, and governmental force is what Friedrich Hayek called the “fatal conceit,”—“the idea that man is able to shape the world around him according to his wishes.” He derived the title from a line from Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations:

The man of system … is apt to be very wise in his own conceit; and is often so enamoured with the supposed beauty of his own ideal plan of government, that he cannot suffer the smallest deviation from any part of it. … He seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces on a chess-board. He does not consider that the pieces on the chess-board have no other principle of motion besides that which the hand impresses upon them; but that, in the great chess-board of human society, every single piece has a principle of motion of its own, altogether different from that which the legislature might [choose] to impress upon it.

For most of my life, this observation drew blood almost entirely on the left, and applause almost entirely from the right. But in recent years, similar men of the system have proliferated on the right. The Peter Navarros and Oren Casses try to make Trump’s actions make sense as an explication of their system.

One of the more amusing problems they face is that Trump hates to concede anything to their expertise, preferring to ground his erraticism as the ingenious product of his instincts. So the right’s new system-men have to rush in after every zig and zag and insist the “plan” is working, like the compulsive gambler who insists every loss is proof that his system is about to pay off.

Now, for the garden. The market system is man-made, just as gardens are. But it is not the product of any individual will. It is a crowdsourced network of institutions, constructed over generations of trial and error, learned best practices, and the accumulation of common law and legislation alike. Just as no one person knows how to make a pencil, no one knows how to create a global system of finance and trade. But, together, over time, we made it. And it has delivered massive abundance.

The problem with the garden system is that when it’s working, you don’t notice its operation. You take it for granted just as you take for granted that you will get light when you flick a switch and hot water when you turn a faucet. When it’s operating properly, the garden system has few active defenders or explainers. This leaves the field vulnerable to people of the gun to promise a better way. The gun people stoke grievances and resentments about how the status quo isn’t doing enough for you. They insist they have a better way grounded in their own righteousness and superior intellect. They tell us that we can keep all of the wealth we have but produce even more wealth if we just do X or Y. We can afford so much more than what the golden goose is giving us. But bad people—“millionaires and billionaires,” “globalists,” corporations, Wall Street, Jooz, demons—are actively preventing you from enjoying the salvific bounty promised by the saviors.

It is only when someone tears down or batters these Chestertonian fences all around us that we discover those fences are there for a reason. Few people think about the value of the dollar as the global reserve currency or of the full faith and credit of America’s bonds until some expert or experts act on their ignorance and ingratitude.

That’s where we are now. One man is singlehandedly taking a plow to the garden because he is confident that he knows better than, almost literally, everyone. And his defenders have few, if any, serious arguments in his defense beyond “trust him.”

Perhaps paradoxically, I’ve come to wish that the champions of the garden had a little more stomach for the way of the gun. I don’t mean that they should use government force to impose their own private nirvanas. I simply mean that I wish that there were more gardeners, more people willing to deny attempts to muck with the system, to dismantle the rule of law, to defend the norms and customs, that have made our manmade system so successful. That’s what the keeper of the English garden is supposed to do. The night watchman state is small—but the watchman is still necessary.

The depressing thing about all of this is what so many on the right have forgotten. The hopeful thing is that many others, on the right and the left, are relearning the value of what they took for granted. I don’t put a huge amount of faith in the notion that the lesson will be permanent, because no lessons are. But when we get through this nonsense, it may be a while before we have to learn it again.

Various & Sundry

Check out our most recent editorial: “Rather than committing to meeting the challenges incumbent upon leaders of the free world, the White House and its ideological allies seem dead set on shedding the job title entirely, as if it were just another target of the Department of Government Efficiency.”

The demon that helped Jonah write this G-File also requests you cast a vote for the Dispatch for a 2025 Webby Award. We’re not saying the demon will follow you around if you don’t, but he is rather persistent.

Canine Update: First, let me offer my heartfelt congratulations to Gus, the winner of the first annual Dispawtcher March Madness Bracket. I’m not normally a “You’re All Winners!” kind of guy. But these were all great dogs, except for the contestants who were, in fact, cats. Those were good cats. Thanks to everyone who participated.

Not too much to report this week closer to home. Zoë has become oddly attached to me of late, eagerly following me all over the house. I don’t understand why, and the Fair Jessica resents it a bit. But it’s kind of nice. One theory is that she’s responding to the collusion of Pippa and Gracie in colonizing TFJ’s lap, even though they do not recognize each other’s claims to that territory. Pippa is just Pippa. She still demands her belly rubs before leaving the house and a personal invitation most days before she’ll agree to receive treats. She’s more selective about when she’ll do her fetching work these days, but she always requires a ball when we leave the house. Yesterday, she had a bit of a gurgly tummy and decided to go to bed before treat time, but she was back at it this morning, albeit a bit rusty on her catching. Chester is back to his daily shakedowns. And the various members of the midday pack, including their buddies Scout and Clover, are doing fine. There was some controversy the other morning when it became clear that raccoons had gotten into our garbage. It’s possible it was some other kind of critter. But just as doctors say—in the spirit of Occam —“when you hear hoofbeats, think horses not zebras,” when I see torn up garbage bags and rifled food products and chicken bones, think raccoons not lemurs. It’s funny, you can always tell there were overnight incursions into our territory the moment we leave the house. Zoë smells evidence of nefarious activity instantly, and it takes me an extra five minutes to get her in the car.

The Dispawtch

Owner’s Name: Alex Keene

Why I’m a Dispatch Member: We cannot escape bias. Mine is that I am conservative, but I am not a Trump supporter. There are few newspapers that provide an outlet for readers like me.

Personal Details: I write a baseball blog on the Cleveland Guardians.

Pet’s Name: Kodiak

Pet’s Breed: Pomsky

Pet’s Age: 7

Gotcha story: My husband lost his dog after he moved to Cleveland, and my aunt happened to be friends with an Amish family looking to sell a pomsky puppy they recently adopted. She sent me a picture, we went over to visit, and he was too cute to leave behind.

Pet’s Likes: Treats, walks, belly rubs, and stealing my spot whenever I get up from the couch.

Pet’s Dislikes: He HATES IT when I try to take a picture of him, I usually have to trick him to look at the camera. He has a near instinctive realization when I take out my phone that a picture is incoming.

Pet’s Proudest Moment: When he finally caught a squirrel in the backyard. I wasn’t paying attention and he bolted behind the house and nabbed it. I made him let the poor squirrel go (who thankfully was not seriously hurt).

Bad Pet: Nobody would dare say such a thing. Kodi is the perfect dog

Do you have a quadruped you’d like to nominate for Dispawtcher of the Week and catapult to stardom? Let us know about your pet by clicking here. Reminder: You must be a Dispatch member to participate.

ICYMI

Weird Links

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.