Happy Tuesday! The Chicago Cubs made a very bad trade last night, and one of your Morning Dispatchers is very angry about it. (Editor’s note: The St. Louis Cardinals and Milwaukee Brewers fans on staff, however, are thrilled.)

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

The House of Representatives voted 275-134 on Monday to boost the size of the stimulus checks in the recently passed coronavirus relief package from $600 per person to $2,000 per person. President Trump has repeatedly voiced his support for the measure, but it was mostly Democrats (alongside a few dozen Republicans) who voted to approve it. The measure now heads to the Republican-held Senate, where it is unlikely to pass—if it is even brought up for a vote at all. Replacing $600 checks with $2,000 checks would cost about $464 billion, according to the nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation.

-

The House voted 322-87 to override President Trump’s veto of the $740 billion National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which funds various national security priorities—including the military. The Senate will vote on whether to override the veto as early as today. Sen. Bernie Sanders said Monday he plans to filibuster the vote until Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell brings the $2,000-per-person checks up for a vote.

-

Nearly 1.3 million people were screened at U.S. airport checkpoints on Sunday, according to data from the Transportation Security Administration. Although the figure is just about half the nearly 2.6 million who flew on the same day last year, it represents the highest single-day tally since the onset of the pandemic in March.

-

The Novavax COVID-19 vaccine on Monday became the fifth to begin late-stage clinical trials in the U.S., with the company announcing it will enroll up to 30,000 people in the U.S. and Mexico to test the safety and efficacy of its vaccine candidate. If the trials are successful, the vaccine could receive emergency use authorization at some point in the spring.

-

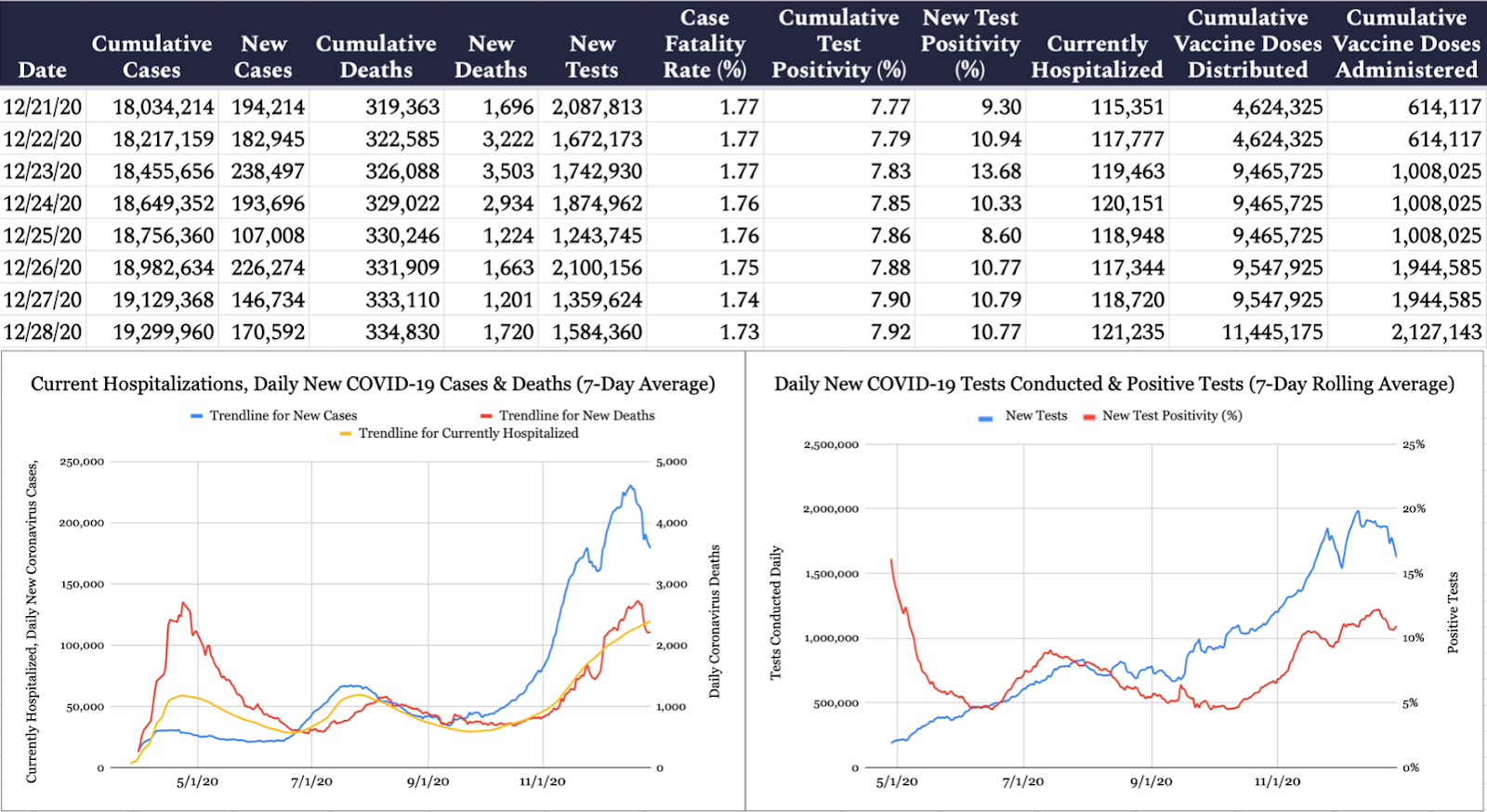

The United States confirmed 170,592 new cases of COVID-19 yesterday per the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, with 10.8 percent of the 1,584,360 tests reported coming back positive. An additional 1,720 deaths were attributed to the virus on Monday, bringing the pandemic’s American death toll to 334,830. According to the COVID Tracking Project, 121,235 Americans are currently hospitalized with COVID-19. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 11,445,175 COVID-19 vaccine doses have been distributed nationwide, and 2,127,143 have been administered.

About That New COVID-19 Mutation …

We wrote last week about the new—and apparently more infectious—variant of the coronavirus that is causing serious concern across Europe, with parts of Britain returning to hardcore lockdown and many countries limiting travel from the U.K. Over the weekend, the United States got in on the action too, implementing a new rule requiring would-be air travelers from Britain to first clear a COVID test before their departure.

The waves of tightening restrictions, attempts to keep infections from hopping national borders, and news reports of individual cases cropping up around the world were an eerie reprise of the opening months of COVID-19, at a time when most of us were expecting a vaccine-distribution race to the finish.

While world governments are taking policy steps to contain the new variant, public health experts have cautioned that this effort may prove fruitless. “We don’t have proof that [the variant] is here, but we do suspect that it is likely here, given the global interconnectedness,” HHS Assistant Secretary for Health Adm. Brett Giroir said Monday.

So, how worried should we be? Is this new variant going to make things worse just as the vaccines should be helping to make things better?

It goes without saying that a more infectious strain of the virus stands to do more damage than its comparatively inefficient cousin. “More infectious” isn’t the same thing as “deadlier”—there’s no reason to believe that a given person will be any worse off if infected with the variant rather than with its predecessor. But from an epidemiological perspective, a mutation that increases infectiousness can actually be worse than one that increases mortality. (A 50 percent increase in transmissibility would result in far more deaths, for instance, than a 50 percent increase in the fatality rate, as mathematician Adam Kucharski spelled out on Twitter.)

At the same time, though, a more infectious strain of the virus isn’t likely to significantly change public health strategy in what we hope will be the closing months of the pandemic—if the only difference is that the new strain is more infectious.

“We still lack formal proof that it is more contagious,” virologist Dr. Paul Offit told The Dispatch. “You don’t want things to become more contagious and more virulent, but that’s not going to change your behavior. If something is more contagious, what are you going to do? You’re going to do masking and social distancing, which you’re already doing. So it’s the vaccine you worry about. If it really does mutate away from the vaccine, that’s the problem.”

It’s this possibility—that the new strain might mutate enough to blunt the new vaccines’ effectiveness—that has caused the most anxiety in recent days. It isn’t that it’s surprising to see new strains of the coronavirus; RNA viruses regularly undergo mutations that lead to such variations. But the new U.K. variant is notable for the surprising number of its genetic differences: 17 total mutations, including eight in the gene that controls the creation of the virus’ signature spike protein. The fact that those spike proteins are the instrument by which the virus attaches itself to the cells it colonizes might explain the apparent increased infectiousness of the new variant—and the spike protein is also the part of the virus that the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines train the body to detect and destroy.

Despite this unsettling fact, however, experts stress that there’s been no hard evidence so far that the vaccines will be any less effective against the new variant than they are against the standard strain, where they’ve already demonstrated rates of disease prevention north of 90 percent. Some preliminary research already exists to suggest that COVID antibodies can hold their own against different variants of the virus, although it will likely be a few weeks before we get hard data about whether that holds true for this particular mutation.

Fortunately, there are relatively straightforward experiments to determine the answers to such questions. After synthesizing the newly mutated spike proteins, for instance, scientists can use convalescent plasma from recovered COVID patients to determine whether antibodies bind to the revised spike as easily as to the original.

Dr. Anthony Fehr, a molecular biologist and expert on coronaviruses at the University of Kansas, told The Dispatch that even if vaccine efficacy is affected, it isn’t necessarily an all-or-nothing affair.

“I don’t think it’s going to take the efficacy of the vaccine down from 95 percent to zero percent,” Dr. Fehr said. “It may take it down from 95 percent to 80 percent effective. But that may not even happen. I think it’s more likely that these mutations may have little to no impact on the vaccine.”

Chinese Journalist Gets Four-Year Sentence

A Chinese court handed down a four-year jail sentence to Zhang Zhan, a 37-year-old independent journalist who provided early coverage of the Wuhan coronavirus outbreak, in a closed-door trial widely regarded as illegitimate by the international community. Authorities convicted Zhang on the ambiguous charges of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” which are often assigned to human rights activists and critics of the Chinese Community Party (CCP). It remains unclear whether Zhang’s lawyers plan to appeal the sentence.

At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Zhang took pictures and recorded footage of life in Wuhan—capturing empty streets and train stations; and full hospitals and crematoriums. Although her reporting garnered little attention at the time, her detainment by the Chinese government has since attracted significant viewership to Zhang’s platforms and earned her the support of activists across China and the world.

Zhang began a hunger strike in late June, drawing media attention to her detainment. Authorities force-fed her with a tube, and Zhang has since fallen seriously ill in jail.

Zhang refused to answer questions from the prosecution during her trial in protest of the proceeding’s legitimacy, and had to be brought into the courtroom in a wheelchair due to her frail condition. Foreign journalists were denied access, and the government refused to air a widely requested livestream of the hearing.

Amnesty International condemned the conviction in a tweet yesterday, pointing to China’s pattern of imprisoning journalists and whistleblowers.

During the brief two-and-a-half hour trial at the Shanghai Pudong New Area People’s Court, prosecutors accused Zhang of sharing “a large amount of false information” to social media since her arrival in Wuhan in early February, and using foreign social media platforms like Twitter and YouTube.

“One of the most noticeable features of Zhang’s indictment is the prominent role given to her interactions with foreign media,” Fred Rocafort, a legal expert on China and former diplomat, told The Dispatch. “This suggests that Zhang’s most serious offense was not speaking out, but validating foreign narratives of China’s handling of the pandemic.”

“The indictment also listed the apps Zhang used to report her findings. The list included WeChat, so foreign platforms were not singled out,” Rocafort added. “However, the mention of Twitter and YouTube (including their English names) sends a not-so-subtle message to resist the temptations of foreign mud.”

Zhang’s documentation of the pandemic’s original epicenter came at a time when Chinese authorities were trying to keep the virus under wraps. A four-page Department of Homeland Security intelligence report released back in May detailed the many ways in which the Chinese government deliberately downplayed the severity of the outbreak, in part to stockpile available medical supplies. Others attributed the CCP’s obfuscation to its desire to save face with both the Chinese populace and other countries.

Dr. Li Wenliang—a 34-year-old ophthalmologist at the Wuhan Central Hospital—was an early victim of the CCP’s suppression of information about the virus. He was censored by police for issuing early warnings about COVID-19, and eventually died of the virus himself.

Some believe that Chinese authorities chose to conduct Zhang’s trial around major Western holidays in an effort to dampen public backlash against the move. Both sides of the American political aisle have been highly critical of Beijing’s behavior the past year, not only on COVID-19, but regarding human and civil rights as well.

Worth Your Time

-

The New York Times sparked a social media kerfuffle over the weekend when it published a story about a black teenager publicizing a years-old video of a white classmate saying the N-word when she was 15. The white student was subsequently removed from the University of Tennessee cheerleading team she was set to join in the fall, and was pressured to withdraw from the university entirely. In a piece for Arc Digital, Nicholas Grossman makes the case that this unfortunate teenage drama was made dramatically worse by adults who should have known better, from University of Tennessee administrators to editors at the New York Times. “It shouldn’t be a national news story,” he writes. “But it is, because social media users, including some adults with big platforms, made it one. To them, these aren’t two random teenagers, but avatars of racist privilege or cancel culture excess; props for culture war arguments, not young people who still have a lot to learn.”

-

After months of working at home in isolation, Americans are increasingly desperate for the face-to-face interactions that accompany a physical workplace, Amanda Mull reports for The Atlantic. “The social by-products of going to work aren’t found only in shared projects or mentoring—many are baked into the physical spaces we inhabit,” she writes. “Break rooms, communal kitchens, and even well-trafficked hallways help create what experts call functional inconvenience.” This, after all, is how most workplace friendships are born. “People end up talking to their co-workers—complimenting a new haircut, asking how the kids are—when they’re corralled together waiting for the elevator or washing their hands next to each other in the bathroom. Over time, those quick encounters build a sense of belonging and warmth that makes spending so much of your life at work a little more bearable.”

Presented Without Comment

Also Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

In a piece for the website, Dalibor Rohac of AEI looks at negotiations between the EU and China on a comprehensive trade deal. Talks have been going on for six years, but Rohac warns that now is not the time for the EU to accept China’s offer. For one, he says, the Chinese are rushing to finalize a deal before the Biden administration takes over. And for another, the deal “would tie the hands of Europeans in controlling Chinese investment in sensitive sectors.”

Let Us Know

What were your New Year’s resolutions last year? Did you stick with them? (If you didn’t, no worries—the whole pandemic thing messed with plenty of our grand plans, too.)

And just a periodic reminder to treat each other with respect in the comments. We’ve noticed an uptick in hostility in recent days; please remember that there’s a real-life human being on the receiving end of your words!

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Haley Byrd Wilt (@byrdinator), Audrey Fahlberg (@FahlOutBerg), Charlotte Lawson (@charlotteUVA), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.