Campaign Quick Hits

2024 FITN Drama: New Hampshire likes its ‘first in the nation’ status. In fact, New Hampshire state law requires that its primary take place at least one week before any “similar election” in another state. They have interpreted “similar” to include only other primaries and not caucuses, which is why civil war hasn’t broken out between Iowa and New Hampshire yet. But Nevada is about to throw down the gauntlet. A bill supported by Governor Steve Sisolak and former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid would “would convert the nominating system in the state to a primary election instead of caucuses” and would require the primary to be held on the Tuesday “immediately preceding the last Tuesday in January,” which would be January 23rd in 2024. New Hampshire, however, has been tested before by upstart states looking to make a name for themselves. Although they had always held their primary on Tuesdays in February or March, the state held their primary in January between 2004 and 2012 to keep their status, voting as early as January 8th in 2008. And, by God, they would surely do it again if they had to, but it’s actually up to the DNC. In an interview with Jennifer Medina at the New York Times, Reid acknowledged that they don’t have any commitments from party officials yet.

Republicans’ 2022 ‘Duh’ Strategy: Two weeks ago, I mocked the Democrats’ ‘the team that scores the most points is gonna win’ strategy message. But not to be outdone, Mitch McConnell gave an equally brilliant interview to the Wall Street Journal last week. Believe it or not, the Republicans’ strategy for taking back the senate in 2022 will turn on “getting candidates who can actually win in November,” according to McConnell. Good to know. But there was one noteworthy nugget in the interview if you can get past the awkward double negative. When asked what role former President Trump should play, McConnell responded, “I’m not assuming that, to the extent the former president wants to continue to be involved, he won’t be a constructive part of the process.” I wonder if McConnell would care to comment on the strategy Steve Bannon told Politico for one of those ‘must win’ Senate states: “Any candidate who wants to win in Pennsylvania in 2022 must be full Trump MAGA.”

Impeachment Blowback: Sen. Lisa Murkowski is the only one of the seven Republican senators who voted to convict former President Trump who is up for reelection in 2022. And now officials in her state of Alaska want Sarah Palin to run against her in the primary. In Ohio, Rep. Anthony Gonzalez was one of 10 GOP members who voted in favor of the article of impeachment. Now, Max Miller, who worked at the White House in a logistics and political role before moving over to the reelection campaign as deputy campaign manager, is set to throw his hat in the ring to challenge Gonzalez. A source familiar told Alex Isenstadt at Politico that Miller has “received six figures in commitments from donors, but that he would have the personal resources to provide self-financing if necessary.” We’ll see plenty more of these announcements in the weeks to come. Trump’s Save America PAC still has $75 million cash on hand and at least one advisor told Mike Allen at Axios that “payback is his chief obsession.”

I spent a lot of time this weekend thinking about recall elections. And there was only one person whose take I really needed. So Sunday night I texted Chris to ask him what he thought about it, and here’s what he had to say…

Total Recall

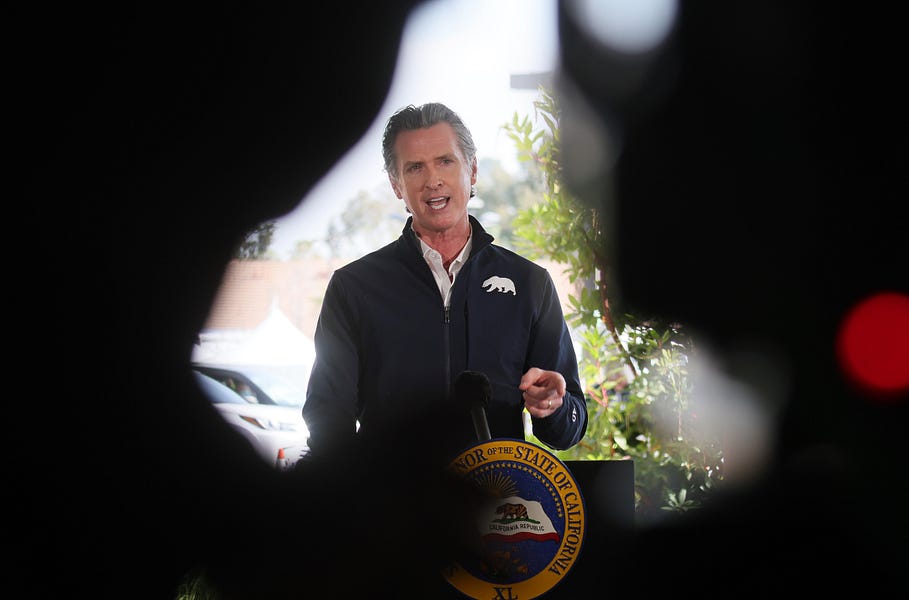

With a recall election effort against California Gov. Gavin Newsom gaining steam, Republicans are very much thinking about 2003. That was when Golden State voters recalled Democrat Gray Davis just a year into his second term and replaced him with Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger. Schwarzenegger would go on to win a full term in 2006, and despite some heartburn over his moves to the left, still represents the California GOP’s most recent statewide success.

But Republicans should spend some time thinking about another state and another recall effort: the 2012 bid to remove then-Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker.

First, let’s have some background on the anti-Newsom bid. Every California governor since Ronald Reagan has faced at least one recall effort. That’s all part of what makes the state so fundamentally ungovernable. Progressive Era direct-democracy provisions make it easy to try to recall officials and to pass referenda. Voters tend to prefer “someone else” and like contradictory policies, e.g. low tax caps and high spending. While 17 other states have recall provisions in their constitutions, California’s is the most permissive. Newsom’s foes need 1,495,709 verified signatures from voters – just 12 percent of the total vote in his 2018 victory – to force the election.

On Friday, the California Secretary of State’s office announced that it had received 668,202 valid signatures as of Feb. 5, but the effort has been growing even since then. Newsom’s epic blunder of attending a donor dinner at the super-swishy French Laundry while the state was under a pandemic lockdown certainly helped. So has overall frustration with the state’s coronavirus restrictions and struggles with vaccinations. The Republican National Committee and some major donors have anted in with some considerable cash. With three weeks to go until the St. Patrick’s Day filing deadline and 22 million registered voters in the state, it seems probable that there will be a recall election late this year.

It’s easy to see the appeal for California Republicans. Beating Newsom when he seeks re-election next year is a long shot. Republican gubernatorial candidates have pulled about 40 percent of the vote in 2010, 2014 and 2018. But in a low-turnout recall election that would feature dozens and dozens of candidates, the GOP might be able to win with a plurality. The ballot would feature two questions: whether to boot Newsom and, if so, with whom to replace him. Since big-time Democrats can’t seek to replace Newsom without at least tacitly backing his removal, it leaves Republicans with a major opportunity. The last recall election featured candidates like Gary Coleman, Larry Flynt and Arianna Huffington. The star of “Kindergarten Cop” seemed like a serious statesman by comparison.

Things are quite different now. While Newsom’s popularity has certainly slipped since his early-pandemic highs, the most recent survey from the Public Policy Institute of California shows him with a 52 percent job approval rating among likely voters. It’s not as high as the 65 percent who gave President Biden passing grades, but it’s higher than when Newsom took office in 2019. At this point in 2003, the institute’s poll found just 24 percent of likely voters approved of Davis’ performance.

But it’s timing that may be the biggest problem for the GOP. If the petition drive is successful, the election would be held late this year—perhaps just weeks before the start of 2022, when Newsom is up for re-election anyway. The argument in 2003 was that three years was too long to wait. But this time first-termer Newsom will have a strong argument to make that he should be allowed to finish his four years. If voters don’t approve, they can give him the heave-ho in just a matter of months. And if he survives the recall, Newsom will likely be stronger when he faces re-election in November of next year.

In 2012, Wisconsin Democrats tried a similar maneuver on Walker, who had been elected to his first term two years prior. The states’ labor groups, furious over Walker’s rollback of public sector unions’ bargaining power, went big on the recall and for Democratic nominee Tom Barrett. But Walker’s policies proved popular enough, and he easily defeated his challenger. When he ran again in 2014, Democrats felt snakebit about Walker. Party leaders struggled to find a serious candidate to take him on.

California Republicans are understandably desperate to find a way back to power, and they have happy memories of 2003. But if they force an unpopular, expensive and annoying recall vote for a still-popular governor with just months to go in his term, California voters may punish the GOP in 2022. That means bad vibes not just for Republicans on the state level but perhaps also in the battleground congressional districts of Southern California that may decide the next House majority.

The other race I am most interested in right now is obviously New York. The race for mayor is always interesting, but this is also about what it means to be in the Biden Democratic Party. Charlotte talked to some of the best people in the business to hear how they see the race taking shape.

History is Happening in Manhattan

It’s a rarity that local elections attract nonstop national media coverage and a jam-packed field of qualified candidates. But to secure the “second-toughest job in America,” more than 40 contenders have emerged to compete in the high-stakes race for New York City mayor. With them comes a tremendous influx of cash, as private donors and super PACs throw their support behind candidates representing different points along the ideological spectrum.

Given the city’s political party makeup—registered Democrats outnumber registered Republicans 6 to 1—the race’s front runners tend to skew left of center. Technology entrepreneur Andrew Yang, City Comptroller Scott Stringer, Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, former Citigroup executive Raymond McGuire, former nonprofit executive Dianne Morales, former Obama administration official Shaun Donovan, and former counsel to Mayor Bill de Blasio Maya Wiley have all announced their bid for the Democratic nomination.

When elected, de Blasio’s replacement will inherit a city battered by the coronavirus pandemic, economic disrepair, and surges in violent crime and homelessness. The outgoing mayor isn’t permitted to run for reelection this year because of term limits, but his chances of securing office for a third time would be slim regardless. De Blasio’s approval rating dropped under 50 percent amid COVID-19 lockdowns and an ongoing feud with New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, who offered up a scathing critique of the city’s leadership and declined to endorse a mayoral candidate last week.

By sole virtue of his name recognition among the city’s Democratic voters, 2020 presidential hopeful Andrew Yang surfaced as the race’s top contender shortly after announcing his candidacy last month. The entrepreneur, best known for advancing a universal basic income, became the fourth Democrat to qualify for New York’s matching-funds campaign finance program in mid-February. But as the race heats up, Yang’s path to victory is far from secure.

“With the bulk of the advertising not yet on TV or in mailboxes, Yang’s poll numbers are a pure reflection of early name recognition from his presidential campaign. That edge disappears when advertising starts in earnest and when other candidates emerge from their Zoom hibernations,” Eric Phillips, former spokesperson for de Blasio, told The Dispatch. “Yang could win, but we’re only in the second or third inning of a nine-inning game at this point.”

Neal Kwatra, a New York City-based Democratic strategist, concurred. “It’s still very early and the race is fluid. Yang, Adams and Stringer have emerged as the early top tier of the field, but Wiley, McGuire and Donovan also bring real assets to the race that could allow them to vault into that top tier ultimately,” Kwatra said. “And Dianne Morales has been an energetic and compelling upstart in this race.”

Another factor muddling the race’s predictability is the introduction of ranked-choice voting in the primary. In a 2019 ballot referendum, New York residents elected to give voters the option to rank up to five candidates in primary elections for mayor. If no candidate secures at least a majority of the vote in the first count, the following choices on the ballot are taken into consideration until one candidate reaches fifty percent or more.

“In theory, the ranked-choice voting in a field with this many candidates will put a premium on each candidate laying out their vision and credentialing themselves with voters. It’s not enough to just win your narrow slice of voters, but you need to be the 2nd and 3rd choice for everyone else,” Jesse Ferguson, the former deputy national press secretary for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign, told The Dispatch. “The ranked-choice system will also make it harder for campaigns to figure out a negative campaign strategy, because they can’t predict whether the voters you peel off one candidate will go to you or go to one of your rivals. The premium will be in contrast—demonstrating your unique value and contrasting it with the field of others.”

Several Republicans have also launched campaigns, but the odds are stacked against them. Billionaire John Catsimatidis—tapped as the right’s best bet at winning the mayor’s office—considered switching parties to improve his chances.

“The Democratic primary is the whole ballgame. It would take a rare-breed centrist Republican to pull off what Rudy did in the 90s or the coalition Michael Bloomberg assembled after 9/11. Let’s remember that Bloomberg had to spend $100 million to get elected—it’s that hard in New York City, even for a moderate,” said Phillips. “The city’s appetite for a corporatist is small and for a conservative it’s non-existent.”

“The New York Mayoral race will be the first, large-scale, post-Trump test of what Democrats want going forward. New Yorkers have faced years of Trump, hardships of the pandemic, and concerns about existing city leadership, so people are going to want someone who shares their values and someone who can get results,” said Ferguson. “My guess is, the candidate who wins will be the one who shows they can do both.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.