Hello, and welcome to a special convention-week edition of The Collision. Thanks for stopping by! We thought this week, with the Republicans in Milwaukee and the immunity question in the rearview mirror, might be quiet in our bailiwick. How wrong we were! We’ll skip the Docket and get right to the big news out of the federal district court in South Florida.

Two days after an attempt on his life and just hours before Sen. J.D. Vance joined the Republican ticket, former President Donald Trump got a piece of good news: Judge Aileen Cannon dismissed the charges against him in the classified documents case in South Florida.

Her decision was not based on the merits of the case against Trump. Instead, Cannon held that Congress had not authorized Attorney General Merrick Garland to appoint special counsel Jack Smith, so Smith therefore was not authorized to bring any charges against the former president.

As we had previously reported, there was no realistic path for this case to go to trial before the election. And if Trump were to be elected, he will almost certainly order his Department of Justice to dismiss the charges under any circumstances. (A president cannot be prosecuted while in office, and how would a president prosecute himself anyway?) The only way that this case was ever going to move forward is if President Joe Biden wins reelection. That remains true.

The Justice Department has already said it plans to appeal this ruling to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit—a conservative court that has already reversed Cannon twice related to this case. Cannon dismissed the charges without prejudice, which also means the DOJ could also ask a United States attorney to refile the case, with Smith reporting to the U.S. attorney. After all, Garland appointed a special counsel because of the potential conflict of interest for Biden political appointees to criminally investigate his chief rival for the 2024 election—but after the election, the conflict is gone.

This decision didn’t come out of nowhere. When the Supreme Court issued its decision in the Trump immunity case two weeks ago, there was a notable concurrence from Justice Clarence Thomas:

I am not sure that any office for the Special Counsel has been “established by Law,” as the Constitution requires. By requiring that Congress create federal offices “by Law,” the Constitution imposes an important check against the President—he cannot create offices at his pleasure. If there is no law establishing the office that the Special Counsel occupies, then he cannot proceed with this prosecution … If this unprecedented prosecution is to proceed, it must be conducted by someone duly authorized to do so by the American people. The lower courts should thus answer these essential questions concerning the Special Counsel’s appointment before proceeding.

Judge Cannon answered the call, holding:

The Appointments Clause is a critical constitutional restriction stemming from the separation of powers, and it gives to Congress a considered role in determining the propriety of vesting appointment power for inferior officers. The Special Counsel’s position effectively usurps that important legislative authority, transferring it to a Head of Department, and in the process threatening the structural liberty inherent in the separation of powers. If the political branches wish to grant the Attorney General power to appoint Special Counsel Smith to investigate and prosecute this action with the full powers of a United States Attorney, there is a valid means by which to do so. He can be appointed and confirmed through the default method prescribed in the Appointments Clause, as Congress has directed for United States Attorneys throughout American history, see 28 U.S.C. § 541, or Congress can authorize his appointment through enactment of positive statutory law consistent with the Appointments Clause.

In short, the Constitution requires that every employee in the executive branch have sign-off from Congress in one of two ways: 1) The Senate can confirm them to their position or 2) Congress can authorize the attorney general to hire them as “inferior officers” by statute. Since Jack Smith wasn’t a Senate-confirmed official, he needed to be able to point to some statute that allowed him to hold this position.

As it turned out, the Supreme Court already looked into this question—way back in 1974. In United States v. Nixon, the court unanimously held that President Richard Nixon was required to comply with subpoenas from special prosecutor Leon Jaworski. In doing so, the opinion said:

Under the authority of Art. II, § 2, Congress has vested in the Attorney General the power to conduct the criminal litigation of the United States Government. 28 U.S.C. § 516. It has also vested in him the power to appoint subordinate officers to assist him in the discharge of his duties. 28 U.S.C. §§ 509, 510, 515, 533. Acting pursuant to those statutes, the Attorney General has delegated the authority to represent the United States in these particular matters to a Special Prosecutor with unique authority and tenure.

Judge Cannon held that this language was not actually part of the court’s holding—nobody had challenged the constitutionality of Jaworski’s appointment and there had been no briefings on that question—-and therefore this language was not binding precedent.

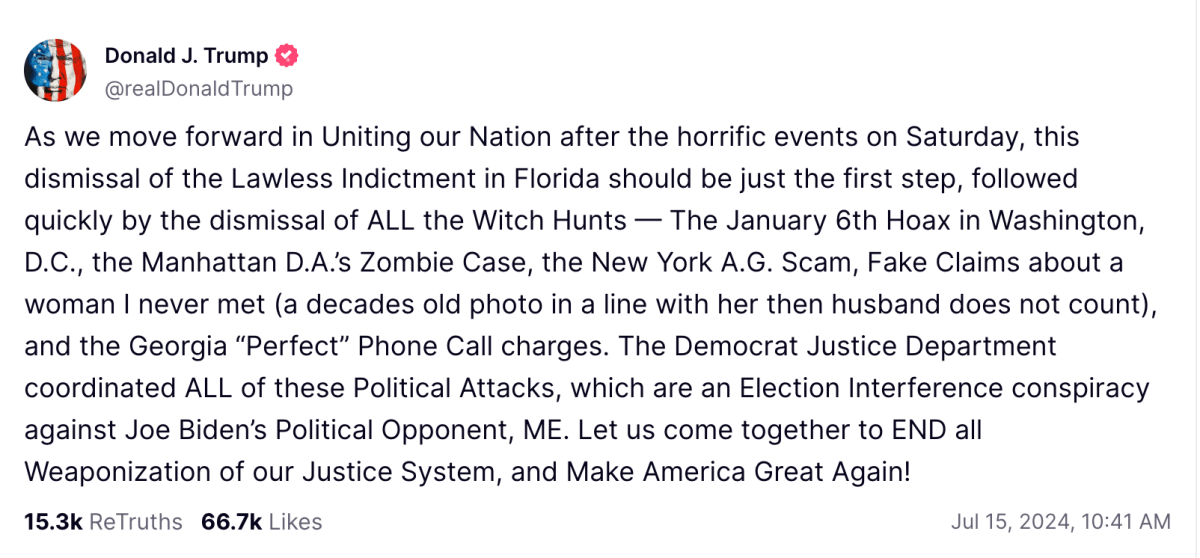

Reactions from commentators were predictably split along ideological and partisan lines. Donald Trump himself wasted no time praising the opinion.

So for those keeping score in the Trump criminal trials at home:

- The federal election interference case is going back to the lower courts after the Supreme Court’s immunity decision;

- the election interference case in Fulton County, Georgia, is on hold as courts consider whether the district attorney, Fani Willis, acted inappropriately;

- Trump’s sentencing hearing in the New York case involving falsifying business records has been delayed to September;

- and now the federal classified documents federal case has been dismissed with the Justice Department appealing the decision.

Is it any wonder Republicans in Milwaukee are feeling really good about their chances this November?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.