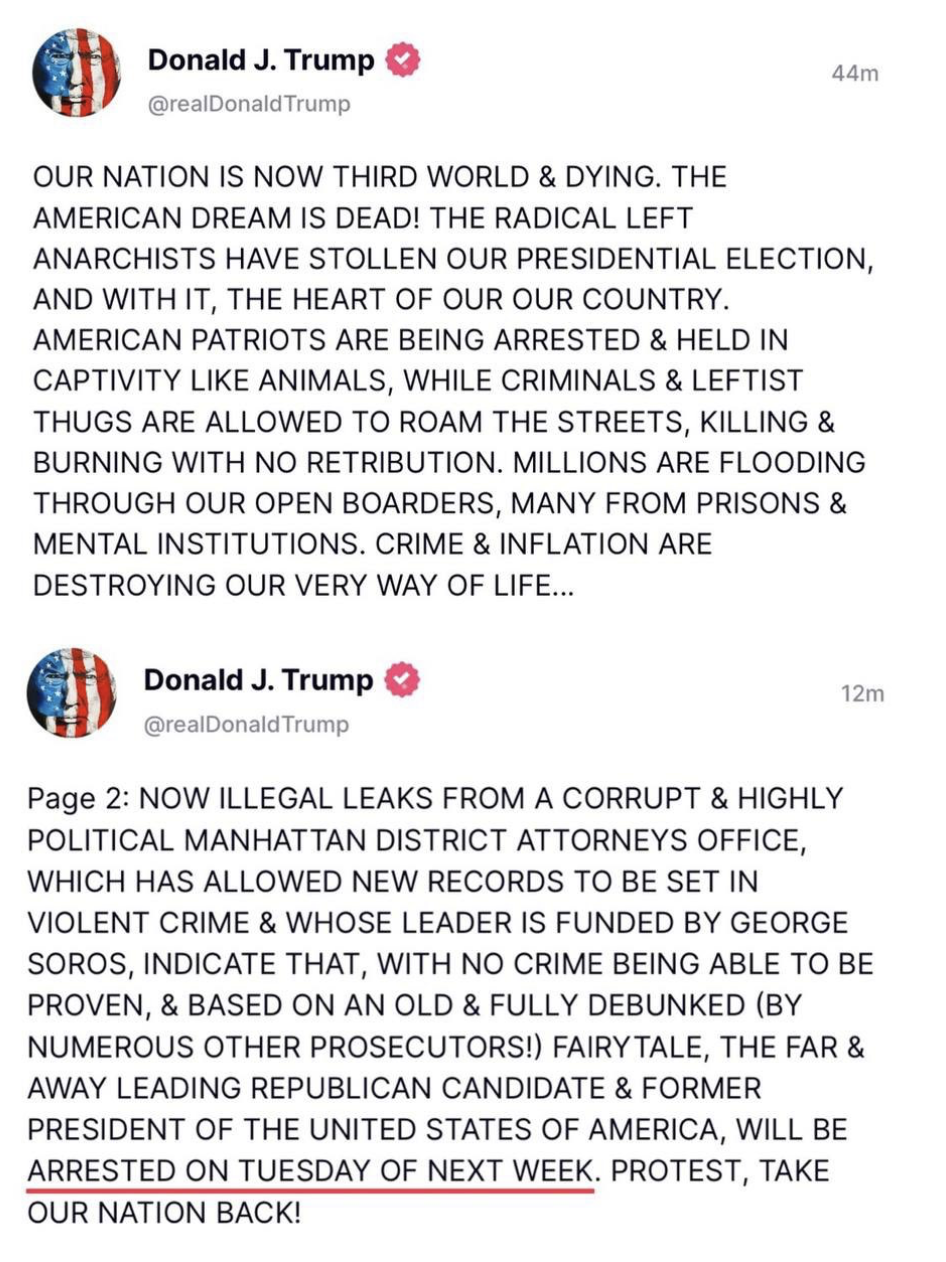

Donald Trump says he is going to be arrested on Tuesday. Maybe. Probably not. There are two things we know for certain about Donald Trump: The first is that he is the sort of irritating New York neurotic who believes that he ceases to exist when attention is not being paid to him, and the second is that he is constitutionally incapable of producing three consecutive sentences without a lie in one of them. A lie that brings him attention must be as irresistible as a well-seasoned hunk of porn-star jerky who pays him postcoital hush money rather than his usual arrangement, which goes the other way around. If you cannot see the hand of divine judgment at work in the prospect of this ailing republic being convulsed over an episode that, by the account of one of the intimately involved parties, had all of the impact of a Vienna sausage landing in a catcher’s mitt, then you have no religious imagination at all.

A few hours after Trump’s claim—in all-caps, of course, from the great sobbing kindergartner of American politics—that he “WILL BE ARRESTED ON TUESDAY OF NEXT WEEK,” a Trump spokesman almost immediately “issued a statement clarifying that Mr. Trump had not written his post with direct knowledge of the timing of any arrest,” as the New York Times gently put it. The spokesman says “there has been no notification,” and people close to the case say that a Tuesday arrest is unlikely, So, more bulls—t from the bulls—t factory. Trump is, of course, calling for protests, as he did leading up to the riot of January 6, 2021, the street-theater complement to the coup d’état he was attempting to orchestrate through various implausible attempts at legal and institutional chicanery.

Donald Trump is, like James Joyce, one of those authors who can be inscrutable on a by-the-word basis and is best appreciated on a by-the-page basis, though if we strung all of Trump’s tweets together and put them in a book we’d still have something less comprehensible than Finnegans Wake. So, at the risk of assuming the position of Stormy Daniels (one of the positions of Stormy Daniels), the enterprising reader must take Trump in at full length, such as it is.

That is not the sort of thing one expects from a man who was, until about five minutes ago, the president of these United States of America. It is precisely the sort of thing one would expect from a delusional bedlamite who invented an imaginary friend to lie to the New York Post about his sex life and then named his youngest son after said imaginary friend. A federal prison is not the only kind of facility one can imagine Donald Trump locked up in. I don’t know whether he is mentally ill in a medical sense any more than I know whether Joe Biden is cognitively impaired in a medical sense, but I do know that, in the colloquial sense of the word crazy, he is as crazy as a sack of ferrets.

Neither do I know whether Trump is guilty of any particular crime—that is why we have trials and juries and such. Trying a former president for a crime, even a petty one, will be a spectacle, though if there is a crime to prosecute, it will be a necessary spectacle: The men and women who hold power should be held to the very highest standards of law and ethics. It is inconvenient that modern liberal democracies have taken away the most useful weapon of civic self-defense in cases such as these, which is, of course, exile. But a country that isn’t ready to repeal the 17th Amendment is not going to reach back in history for such a golden oldie as exile.

What is remarkable to me is that, all these years after the fact, the Trump admirers are still complaining that Hillary Rodham Clinton called them “deplorables.” The Clintons are awful and embarrassing and gross—Roger Stone has been known to plagiarize my line about the Clintons’ being “the penicillin-resistant syphilis of American politics”—but, if all this isn’t deplorable, what is?

Economics for English Majors

The idea is not unique to me, by any means, but I have received many questions about my suggestion that the FDIC should, as a matter of prudence, insure all bank deposits rather than only the first $250,000.

One line of criticism goes, roughly: “Why should the FDIC insure the fat cats with tens of millions of dollars, or billions of dollars, in the bank?” Answering that question will depend on what you think deposit insurance is there to do. If you think of deposit insurance as a social-justice measure—ensuring that regular people of modest means don’t pay a disproportionate financial price if bank executives do a poor job managing a financial institution—then means-testing deposit insurance (which is what the cap amounts to) might make sense. On the other hand, if you want to use deposit insurance to influence the behavior of bank depositors, preventing widespread financial panics and runs on banks, then it makes sense to insure the big accounts, too: It is, after all, a much bigger problem for a bank when a guy with a gunny sack walks up to the teller’s window and asks for his $1 billion back than when somebody with $5,300 (the median bank balance) does. This would require congressional authorization, of course—we’ve already had enough administrative freelancing in the past 20 years to last us the rest of this century—but, as an economic and regulatory proposition, the idea is sound. As a general rule, insurance gets more efficient the larger the insured population is, and charging banks (and, through them, their customers) an economically appropriate premium for deposit insurance is the sort of thing a reasonably functional government ought to be able to do.

There already exists a version of this, confined to Massachusetts, where the Depositors Insurance Fund (DIF), a private, bank-financed deposit-insurance company that covers deposits beyond what the FDIC guarantees, has been operating since the 1930s. The DIF is available only to Massachusetts-chartered banks, though the protection is extended to the out-of-state customers of those banks and out-of-state branches, as long as the bank is legally a Massachusetts bank and DIF participant.

I frequently quote F. A. Hayek on the welfare state and social insurance in The Road to Serfdom:

In a society which has reached the general level of wealth which ours has attained ... some minimum of food, shelter, and clothing, sufficient to preserve health and the capacity to work, can be assured to everybody. ... Nor is there any reason why the state should not assist the individual in providing for those common hazards of life against which, because of their uncertainty, few individuals can make adequate provision.

Where, as in the case of sickness and accident, neither the desire to avoid such calamities nor the efforts to overcome their consequences are as a rule weakened by the provision of assistance –where, in short, we deal with genuinely insurable risks—the case for the state’s helping to organize a comprehensive system of social insurance is very strong. There are many points of detail where those wishing to preserve the competitive system and those wishing to supersede it by something different will disagree on the details of such schemes; and it is possible under the name of social insurance to introduce measures which tend to make competition more or less ineffective. But there is no incompatability in principle between the state’s providing greater security in this way and the preservation of individual freedom.

In my view, the interesting and useful part is “those common hazards of life against which, because of their uncertainty, few individuals can make adequate provision.” Market competition really does contribute to improvements—improvements in quality, improvements in price—for all sorts of goods and services. The consumer-choice dynamic works best in markets where there are lots of sellers and lots of buyers—and lots of repeated, ongoing interactions. You use your mobile phone every day, and you get a new one every couple of years, maybe every year. So you are on the lookout for the next improvement, and manufacturers have a very strong incentive to provide it. But bank failures are very, very rare—thank goodness. How many of you asked a lot of pointed questions about reserve-capital allocation strategies when you opened up your last checking account? My current bank has been my bank through seven places of residence in five states, going on 20 years. I know what kind of shocks are on my truck—I have no idea how my bank runs its internal affairs. I just assume they are evil but competent—you know: bankers.

(And I work hard to keep my bank balance under that $250,000 FDIC ceiling!)

In any case, relying on consumer pressure to keep banks on the straight-and-narrow does not seem to have worked very well, nor does it seem very likely to work. Maybe in 10 years somebody will have cooked up some financial innovation that makes old-fashioned depository banks beside the point, but, for now, individuals use banks, families use banks, and businesses use banks, and it seems to me that we would probably be better off as an economic matter if people didn’t have to worry about their bank deposits. And don’t think that you’re in the clear just because you are under the $250,000 limit—if a jumbo depositor or a couple of dozen of them decide to pull out of your bank, that could tank the institution. Sure, the FDIC promises to step in and make you whole, but there is bound to be some disruption, some risk, and some uncertainty. That kind of uncertainty is the archenemy of long-term prosperity in a free-market economy.

(Obligatory reminder that The Dispatch was a customer of Silicon Valley Bank, the failure of which started this whole conversation.)

Insuring all deposits would harden up the U.S. commercial banking system. So would raising banks’ capital requirements (the cushion they have to maintain against deposits) and tightening up a few other rules. The problem, of course, is execution. If I had been around when the FDIC was being created, I probably would have argued against it, but we have an FDIC and it has done a pretty good job, for the most part. But not a perfect job: As some of you may know, for the decade leading up to the financial crisis of 2007-08, the FDIC basically stopped collecting insurance premiums, believing that it had all the reserves it needed to get through any foreseeable emergency. But we don’t maintain the FDIC just for foreseeable emergencies—we maintain it for unforeseeable emergencies, too.

Mandatory comprehensive deposit insurance and regulatory reforms such as increasing capital requirements will make banking more expensive and make banks less efficient, and that may lead some very large and very risk-friendly businesses to explore non-bank options. That will create new risks, challenges, and costs, and we should be open-eyed about that kind of thing. And if there is a lesson to be learned from such episodes as the junk-bond mess of the 1980s to the turn-of-the-century subprime-mortgage meltdown, it is that attractive returns will sometimes lead small-time investors and big institutions alike to make bets they cannot afford to lose. (Junk bonds, which are high-risk and high-yield investments, make sense for some large, diverse, and sophisticated institutional investors. They do not make sense for two soon-to-retire schoolteachers looking for some place to park their life savings.) So when Uncle Buck tells you about this great new thing that isn’t exactly a bank but pays you 11 percent on your savings account—be skeptical.

There was a time when banks were boring. Boring banks are the kind of banks you want to have.

Words About Words

Tell a woman that she’s “isn’t photogenic” and you’ll hurt her feelings; tell her that “pictures don’t do you justice” and she’ll take it as a compliment. Of course, you’re saying the same thing in both cases—that she looks better in person than she does in photographs—but we have come to treat photogenic as though it were a synonym for attractive—which, strictly speaking, it isn’t. A remarkable thing that I noticed writing about movies and theater is how many famously beautiful people are, in reality, even more beautiful than you expected from seeing them on screen and in pictures. Gwyneth Paltrow is one such, Kate Winslet another. Clint Eastwood in his early 80s (I think he was 82 the one time I encountered him) looked like more of a movie star in person than he had on screen in probably 40 years. In that sense, photogenic may be the opposite of a compliment: Even before the ubiquity of vanity filters and the like, it was not uncommon to meet someone who is much less attractive in person than in pictures.

Words relating to attractiveness and appearance can get pretty dicey. Zaftig, a Yiddish-derived word that has enriched English, is, if you are going by the book, a term of praise. Usually applied to a woman, it means pleasingly plump—the literal definition is succulent or juicy—but you would be playing Russian roulette if you used it to describe a living woman. A recent scan of the word’s usage in newspapers turns up a reference to a sea turtle, a film-and-television production company, a Vogue article on a fashion trend described as the “Torah-teacher aesthetic,” and a Jewish Journal review of Melissa Broder’s novel Milk Fed bearing the headline, “The Rise of the Orthodyke,” which means pretty much what you are guessing it does. A disproportionate share of the uses I found in recent publications appeared in Jewish-oriented stories and/or in Jewish publications—not surprising for a word of Yiddish extraction.

Statuesque once was a common description of a woman (the lexicon relating to female beauty is, naturally, much more extensive than that describing men) whose solidity and form suggest that she ought to be carved in marble. There’s a funny scene in The Wire in which a gaggle of newspaper editors on a cigarette break lament the passing of certain journalistic clichés, and one asks whatever happened to all the “statuesque blondes.” (No good ever comes to someone identified as “honors student” in a newspaper. And the editors also observe the difficulties facing “mother of four,” another recurring character: “You ever notice how ‘mothers of four’ are always catching hell? Murder, hit and run, burnt up in rowhouse fires, swindled by bigamists.”) Buxom means approximately the same thing as zaftig, but it has fallen into disuse after becoming very strongly associated with breast size, making the word sound pruriently quantifying. Comely and comeliness have both nearly disappeared from modern English not because they came to be used pruriently but because they contain the sound of a profane sexual term. (The word niggardly, which has nothing to do with the racial insult, has gone into hiding for the same reason. Even rhymes can be a minefield: There’s a bit in the cop movie 21 Bridges in which a police officer refers to a pistol-happy black colleague as a “trigger,” to which the detective, played by the late Chadwick Boseman, responds, coldly: “You better have perfect diction.”) Stripped (if that word may be allowed in the context) of the dirty-sounding adjectives, English is left with a lot of very, very stuffy ones to do the work at hand: pulchritude, beauteousness, resplendency—too starchy even for me, and I like extra starch in my prose.

Going through some old slang, there are some fun words for beautiful people, including sockdolager, which is literally a knockout punch—knockout, though it sounds old-fashioned, is still used in that way, and the sock of sockdolager still means punch. In the play Our American Cousin, one character says to another: “Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal, you sockdologizing old man-trap.” Apparently, that was a laugh line, but the laughter wasn’t loud enough to drown out the report of the Derringer pistol John Wilkes Booth fired at that moment in the play’s most infamous performance.

In Other Wordiness ...

Some of you very generously assumed that I was making a joke last week about the term drawing room. I assumed that there was a back-story there, but I didn’t know what it was, though many of you did: Drawing in this instance is an abbreviation of withdrawing, and before there were drawing rooms there were withdrawing chambers, meaning a parlor or salon to which hosts and guests would withdraw following dinner. To draw is to make something move by pulling it—you can draw water from a well or draw a saw across a board or withdraw a sword from a stone—and draw in the sense of making a picture comes from drawing a pencil or other implement across a piece of paper. English generally prefers economy: Once, you would draw the pencil across the paper to make a picture of the cat, but now you just draw the cat.

It isn’t easy to draw a cat. I once heard an art critic insist that most practitioners of Abstract Expressionism were frauds who couldn’t draw a cat and make it look like a cat if their lives depended on it, whereas Kandinsky could draw or paint Notre-Dame de Paris if he liked, but what he liked was whatever you want to call this kind of thing.

Pulchritudinous!

Elsewhere

If you haven’t had enough of me on banks, then here is some more.

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

In Closing

If you really want entitlement reform, don’t send an American conservative to do the job—what you want is a slightly rehabilitated French socialist.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.