You are not Alexander the Great. Neither am I. We do not have the option of simply cutting through the Gordian knot—we must untangle it, strand by strand, one maddening little bit at a time, an exercise that can seem pointless until you reach that satisfying moment when you can see how the thing finally will be unwound.

In the matter of Donald Trump, the serial bankrupt game-show host who was, incredibly enough, once the president of these United States, there are two tangled strands: the legal issues and the political issues. Each strand is further subdivided into many more tangled threads, which on the legal side include the January 6 matters; the more significant failed coup d’état in the form of the attempted nullification of the rightful election of Joe Biden under a host of preposterous legal pretexts; the classified documents matter; the attempt to suborn election fraud on Trump’s behalf in Georgia and elsewhere; the matter of business fraud in Trump’s account of his bribe to pornographic performer Stormy Daniels to keep quiet about his adultery with her; the civil matter of whether Trump has again defamed the writer E. Jean Carroll, who already has won a civil case in which she alleged that Trump sexually assaulted and defamed her.

There are fine legal distinctions to be made, of course. These do not, in general, do very much to support the position that Donald Trump should be elected president again. For example, Trump’s lawyers have taken issue with the use of the word “rape” in the Carroll matter, producing this response from the judge in the case:

The finding that Ms. Carroll failed to prove that she was ‘raped’ within the meaning of the New York Penal Law does not mean that she failed to prove that Mr. Trump ‘raped’ her as many people commonly understand the word ‘rape.’ ... Indeed, as the evidence at trial recounted below makes clear, the jury found that Mr. Trump in fact did exactly that. ... The jury’s finding of sexual abuse ... necessarily implies that it found that Mr. Trump forcibly penetrated her vagina.

It bears repeating that this is a judge—the judge overseeing the case in question—writing in his professional capacity. This isn’t an MSNBC panelist engaged in maximal spin. Nor are your eyes—or your memory—deceiving you about the events of January 6, the piles of classified documents stacked in the toilet at Mar-a-Lago, the transcript of that “perfect” telephone call to the election officer in Georgia, that $130,000 hush-money payment to Stormy Daniels. If you have followed Donald Trump’s career at all, you know that his entanglement with Stormy Daniels wasn’t even his first involvement with the pornography business.

That sound you hear is 40 million right-wing evangelical fingers going into 40 million right-wing evangelical ears and 20 million grimly pious mouths chanting, “Nah! Nah! I can’t hear you!” But, “Woe unto them who call evil good and good evil, who justify wickedness for profit.”

You are not imagining any of this. Hunter Biden may be a reckless dope fiend—he may even be, as the math would suggest, a clown made of crack in some parallel universe—but none of that changes the facts of the case against Trump.

(“The Case Against Trump”—somebody should write a pamphlet with that title.)

I am no kind of lawyer, much less the kind who prosecutes or defends cases such as these, to the extent that there are “cases such as these.” My amateur status being stipulated, I generally agree with the lawyers around here and elsewhere in my own orbit, whose judgment as of this moment is that the documents case is the most likely to produce a felony conviction of Donald Trump, the New York business-records case the least likely, and the matter that we put in the box labeled—wrongly—“January 6” full of uncertainties and complications that make it very difficult to foresee the outcome.

The “January 6” business—and I put it in quotation marks because the sacking of the Capitol on that infamous day, grotesque as it was, was a relatively minor spectacle accompanying the actual attempt to overthrow the government happening elsewhere, the would-be courtroom coup with the phony electors and the rest of it—is particularly vexing. It is one of those things that make you say, “There ought to be a law ...” It is, in fact, one of those things that it is very difficult to believe that there isn’t a law against. Jack Smith no doubt will make a masterly attempt to show that Trump committed felonies in that matter, and he may well prevail.

Trump’s team seems poised to make a First Amendment defense. That isn’t as straightforward as you might assume: If a mob boss says to an underling, “I wish somebody would drop Joey Coconuts into the Schuylkill River for good,” he doesn’t necessarily get a free-speech get-out-of-jail free card, even if he didn’t say, “I want you to murder Joey Coconuts, and I’ll pay you $5,000 to do it.” But, at the same time, the First Amendment probably does protect a few hundred sobbing permutations of “I wuz robbed!” And if dishonest allegations of election fraud are a crime, then a whole lot of Democrats should have gone to prison after the 2004 presidential election. That isn’t “whataboutism”—it is a reminder that there isn’t a federal statute prohibiting ordinary garden-variety lies.

Yes, Trump was engaged in much more than that, but it’s no good pretending that a brick wall isn’t made of bricks, and it will be very difficult trying to show that 10,000 actions, each legal on its own discrete terms, somehow add up to a crime—a crime in the legal sense, not a crime in the moral sense.

Lawyers and their clients can be fined for abusing the legal system, or attempting to abuse it, through frivolous lawsuits. Indeed, Trump and his lawyer Alina Habba were ordered to pay just shy of $1 million in January of this year over a bogus lawsuit filed against Hillary Clinton and other political enemies some years ago. But, because we want people to feel free to go to court to seek redress of actual wrongs, there are limits to that sort of thing. Because we want there to be a free and open political discourse, there are limits to the kinds of sanctions that we can impose for political communication, including dishonest, irresponsible, and dangerous political communication. That Donald Trump is a villain in the transcendental sense is obvious to anybody with eyes—proving that Donald Trump is guilty of a felony to the satisfaction of a jury under the rules of our criminal-justice system is a much less certain thing.

The legal question is not our only question: The law may not be able to punish Trump for simple lies, or even for weaponized lies, but that doesn’t mean that we, as a republic, are powerless to act—if we choose to act.

That brings us to the other major strand: The many, many offenses of Donald Trump that are, by any honest and intelligent account, evil even in those cases in which they are not criminal. In our political culture, these distinctions land a bit differently than they do in, say, the European Union, where, to take one example, a Holocaust denier or a Nazi revanchist could be prosecuted as a criminal for acts and speech that would, under our rules, be protected by law even as the wickedness of such an inclination was generally acknowledged. (Indeed, institutions such as our First Amendment are necessarily only for those ideas and positions that seem evil to some non-trivial group of people—the kind of political ideas that nobody objects to do not require much protection.) That is not to say that Donald Trump did not commit any crimes in his attempt to hold on to political power after losing the 2020 election—it is to say that proving him guilty of crimes is a complicated and difficult thing.

What is neither complicated nor difficult is—or should be—the judgment that happens outside of the court of law. Of course, Donald Trump was manifestly unfit for the office he sought—or any office of public trust—in 2016. He was known to be unfit for any position of trust, at least by such people who knew of him at all, back when parachute pants were in fashion and “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go” was on the radio. Trump is unfit for office, and the people who work for him today are unfit for public trust as well: Susan Wiles, Jason Miller, spokesman Steven Cheung, and the rest of Trump’s 2024 team would, in any self-respecting society, be pariahs and kept as far from political power as is possible in a society that does not use exile as a political sanction. The 54 percent of Republicans who tell pollsters they support Trump in 2024 deserve every bit of the contempt and derision they will receive, and the 2024 Republican hopefuls who cannot quite manage to say the plain things about Trump in plain language have no business seeking the most powerful office in the government of the most powerful nation in the world.

History is testing Nikki Haley, Tim Scott, Ron DeSantis, et al., and they are failing that test. Mike Pence, who advertises himself as a man of faith, ought to face the fact that he is never going to be president of these United States and instead of worrying about his moribund career pay some attention to the state of his immortal soul—which is the only thing of real value he has left, having forfeited his reputation, his self-respect, and any claim on the respect or goodwill of his countrymen. But Trump has a relentlessly degrading effect on the people around him: Ted Cruz, having been relentlessly humiliated by Donald Trump and having acquiesced to the humiliation of his wife at the same time, would walk barefoot through the snow like Henry IV at Canossa if he thought he would get a pat on the head from Trump in return. Even Sen. Cruz doesn’t dispute the facts of the case, of course—how could he? He is still in possession of a working brain—it his soul that he sold.

But what are the facts of the case to such a man as Ted Cruz? To Sean Hannity? To 54 percent of Republican voters?

Sycophant is an ugly word, but it isn’t ugly enough for Republicans in 2024. The judgment on Trump is, necessarily, a judgment on the Republican Party as a whole, on those who adhere to it, those who make excuses for it, those who cannot bring themselves to call it what it is. What do they do? Mutter about how “it wasn’t really rape, you know, according to the New York Penal Law.”

I do not know how any one of these trials is going to turn out. But, at a certain level, I don’t need to. And neither do you.

That is because the uncontested facts of the case—of the cases—are enough to disqualify Donald Trump from any position of trust. We all know this. Ted Cruz knows it, Sean Hannity knows it, Rudy Giuliani, in his rare lucid moments, knows it. There isn’t any dispute about whether the affair with the pornographic performer happened or whether money changed hands to facilitate its conclusion more conveniently; there isn’t any question about whether Trump had piles of classified documents sitting beneath the gilt chandelier of the Mar-a-Lago toilet; there isn’t any question about the fact that Trump did, in fact, try to nullify the 2020 election and unconstitutionally hold on to power. These uncontested facts ought to be understood as dispositive. The fact that they have not disqualified Donald Trump in the hearts and minds of Republican voters is not a judgment on Trump—it is a judgment on Republican voters.

Economics for English Majors

Speaking of First Amendment defenses—some years ago, during the 2007-08 financial crisis, there was some talk of taking action against the big credit-rating agencies—Moody’s, Standard & Poor, Fitch—that had put gold-plated ratings on mortgage-backed securities and related instruments that turned out to be hot garbage. The first line of defense for the credit-rating agencies was going to be free speech: They are paid to give their opinion about the creditworthiness of institutions and instruments, and they are allowed to be wrong.

Fitch has now downgraded the credit of the U.S. government, sending the Biden administration into an enraged lather. (It is hard to tell when Janet Yellen is enraged, I know, but, if you look closely, you’ll see it.) What that means is that a few days ago Fitch had judged the U.S. government to be the most creditworthy institution in the world, or equal to other institutions also enjoying its very highest rating, but, now, it judges the U.S. government to be one degree short of that standard. This is the second time in modern U.S. history the government has been given a downgrade. The reason for dinging the federal credit rating is what you would think it is: bad governance when it comes to fiscal issues, big and bigger deficits, rapidly accumulating debt, expected deterioration in the fiscal situation and in the overall economy, etc. As ABC News put it:

Analysts downplayed the immediate economic effect of the rating decision but said it marks a significant milestone on a path of increasing debt that could ultimately raise the nation's borrowing costs, threaten economic growth and hike interest rates for consumer loans like credit cards and mortgages.

So, what it means: Not much.

That seems to be the consensus, anyway. Some big institutions hold U.S. government debt because they more or less have to, some because they want to, preferring dollar-denominated assets to those attached to other, less credible currencies; demand for U.S. government debt is intimately related to demand for U.S. dollars, which are sought-after because they offer a good store of value and because many international deals and settlements (e.g., payments for oil deliveries) are denominated in U.S. dollars. Nobody at the People’s Bank of China or Morgan Stanley or Blackrock or ExxonMobil needs Fitch to tell them what the fiscal situation of the U.S. government is. They know whether they want to hold U.S. government securities, how many they want to hold, on what terms they want to hold them, etc. The only people who really care what the ratings agencies say are institutions that have to care for regulatory reasons and politicians who are embarrassed by the downgrade.

We have had cheap, cheap, cheap money for a very long time. We have got used to it and have baked all sorts of assumptions about cheap money into the economic cake, both in the public sector and in the private sector. Do you know what the average rate for a 30-year fixed mortgage was in 1982? It was 16.04 percent—rates are less than half that today, and people in the real-estate world are weeping tears of blood like Le Chiffre. Around the same time, Treasuries were paying about 15 percent interest—great if you wanted a low-risk portfolio, but tough if you were the federal government trying to borrow money. If interest rates were at 1980s levels with today’s debt load, the federal government would be obliged to pay about $5 trillion a year in interest—which is more than the federal government collected in all taxes combined in 2022, or about 80 percent of combined federal spending for 2022.

That’s why you care about the creditworthiness of the federal government—real or perceived—even if you don’t care very much about Fitch’s downgrade per se.

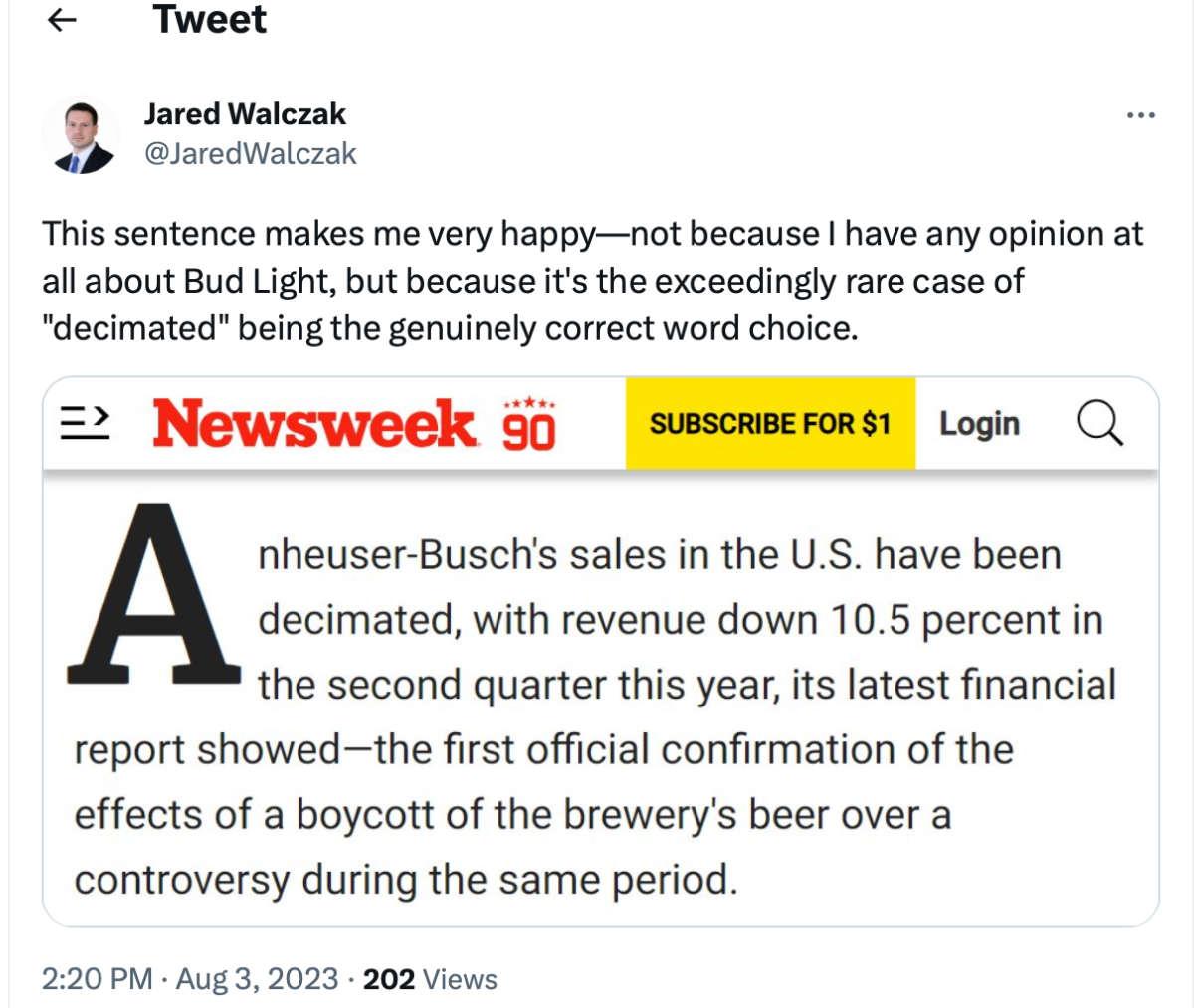

Words About Words

Here is a weird sentence from the Wall Street Journal:

Woung-Chapman, whose ancestry includes Chinese, German, Indian and African, says she liked how intensely curious Chapman was about her background.

There’s a noun missing. We have a string of national adjectives—Chinese, German, Indian, and African—modifying ... nothing. You can see how it would be a tricky sentence, because the noun you want there is “ancestry,” which already appears earlier in the sentence and which, therefore, would sound repetitive, having already appeared earlier in the sentence. But people can get pretty queasy about words related to ancestry if they feel too emotionally or socially loaded: For example, the writer could have written about “Chinese, German, Indian, and African blood,” but blood as a shorthand for ancestry can sound creepy in some circumstances, and the history of the idea of “one drop of African blood” in the American context is kind of lurking in the background. Paternity, heritage, and words of that sort also have undertones that can make some writers nervous. The author could have substituted background for the first ancestry and then used ancestry later in the sentence, or used a word such as antecedents or the more precise progenitors. But a string of adjectives modifying an invisible mystery word doesn’t really work—in fact, it draws attention to the very thing one assumes the author was, consciously or unconsciously, attempting to avoid.

In Other Wordiness ...

Elsewhere

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

In Closing

Sometimes, it is necessary to resist the temptation to be liked. Everybody wants to be liked, but it isn’t always the right thing.

I was sad to read about the death of Patrick Cates, who had been the principal of Highland Park High School in the eponymous affluent Dallas enclave and, many years before taking that job, my senior English teacher at Lubbock High School. Mr. Cates was not the kind of teacher you liked—his natural affect, at least at that point in his life, was not warm. But he was the kind of teacher who did his students an enormously important service: He was serious, precise, demanding, and demanded that we be serious and precise in his class. On the first draft of the first big paper students submitted for his class, almost every student—and this was an honors class full of very competitive kids—received a failing grade on grammar and usage. For some of them, it was the first failing grade they ever had received on an assignment. This had the wonderful effect of awakening students to the fact that these considerations are important and that grammar and usage have to be studied and learned, that what sounds correct to us isn’t necessarily correct. Poetry may be sublime and ineffable, but there was, in Mr. Cates’s classroom, a right way to write about it and a wrong way. He wasn’t a teacher I loved or one who left me with fond memories, but he did his job and, in doing so, did us all a lot more good than we might have noticed at the time. Job well done, Mr. Cates.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.