Words are magic, and magic, historically, was largely made up of words. There is, of course, the “magic word,” which isn’t always “please,” and mumbo-jumbo words such as “abracadabra,” and old magical traditions having to do with “true” or “hidden” names. Secret true names are a thing in Kabbalah, in Plato, in cultures ranging from Germany to Egypt, from the story of Rumpelstiltskin to the plot of Turandot. It is pure superstition, of course, but ancient and honorable superstition. But the just-right word can be a powerful thing, as Mark Twain famously observed: “The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter—it’s the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning.”

Weird?

Yup.

Here’s a little bit of context from the early 21st century, and a theory for why being called weird gets up Republicans’ noses in such a powerful and delightful way: It all started 15 years or so ago with pickup-artist blogs. If you were reading widely in the Anglophone digital sphere circa 2010, you surely noticed that, almost all at once, there came into being a great deal of half-educated talk about “alpha males,” much of it based on a little dollop of half-understood evolutionary psychology popularized by blogs (some of them very amusing, at least at first) dedicated to giving unhappy men advice about how to build a happier love life. (Or at least a more active sex life.) The advice was mostly pretty simple: Because of the fundamental facts of mammalian reproduction (often expressed in economic terms: “Eggs are expensive, sperm are cheap”), men are more inclined toward promiscuity and women are more inclined to status-based selectivity. (I have written about these ideas off and on over the years with varying degrees of seriousness.) And so the best strategy for men is either to achieve high status or to ape the mannerisms and habits of high-status men in order to fool women into reacting to them as though they were high status. Because the social organization of human communities is radically different from the social organization of a lion tribe, there actually isn’t any such thing as an “alpha male” among Homo sapiens, but there is some truth—some—to the broader point about status and selectivity.

It is easy to run away with the idea, though, and people have indeed run away with it. Those under 30 may not remember a time when the internet was not full of loveless idjits and masturbatory blowhards talking about their “alpha” status.

A whole lot of what we think of as the New Right is culturally based in that world. You can get an earful of it from so-called “barstool conservatives” and the men’s-rights movement, but you don’t even have to go that far. On a recent episode of The Dispatch Podcast, Jamie Weinstein asked Newt Gingrich a pretty straightforward question about U.S.-Russia relations, and Gingrich—who is, let us not forget, formerly the speaker of the House and at one time the most powerful Republican elected official in the country—responded with a long, bizarre, homoerotic reverie about Donald Trump’s status as an “alpha male.” It was ... what’s the word?

Weird.

Very.

One of the things you might have noticed if you were reading those blogs a decade and a half ago was the unquestioned consensus that the worst thing a woman could call a suitor was weird, or some variation such as weirdo, followed by creepy/creep and other near-synonyms. Weird wasn’t just a criticism or a prelude to rejection—it was emasculating. It was an assertion of the target’s low status, his inability to master his social environment, etc. Weird was the word you heard before deciding to cut your losses and move on to the next victim object of romantic attention. It was the sexual death knell.

If you are so inclined—and I do not advise that you be so inclined—you can go to Google right now and read questions on various online fora from men who have been called weird by a woman and who are desperate for some advice about how to respond. Much of the old pickup-artist lingo is still in use, having become something of a literary tradition in certain unhappy corners of the digital world. That “alpha male” stuff is all over the place when it comes to Trump and Trumpism, from 2016-era exegeses to homoerotic Trumpist performance artist Nick Adams to this summer’s headlines, including this in U.S. News and World Report: “Trump Shooting Makes Him Stronger, Channeling Alpha Males Back to Teddy Roosevelt.” The Trump movement’s embrace of campy emblems of exaggerated masculinity—the cowboy hats, the biker gear, etc.—is straight out of 20th-century gay erotica. So are many of the depictions of Trump himself:

There he is, the president of the United States, sitting astride a motorcycle in a leather jacket in front of the Capitol, a rifle in hand. There he is again, once more leather-clad, both of his middle fingers extended as he stands on the southern border.

The words written on the T-shirts and denim vests alongside the imaginary biker version of Donald Trump exude similar vibes. “Finally someone with balls.”

The fascination with Trump’s genitals is a genre convention. But that’s not all!

The language is foul. The wardrobe is leather. Engines are loud, as is the music. Booze flows freely. Tents sell chaps and vests with gun pockets. You can smoke where you like for the most part. There are daily wet T-shirt contests. In the most raucous bar, men pay women in lingerie to spank their bare bottoms with a paddle.

Weird?

You bet your leather chaps it is.

Weird in this context isn’t just another word for odd. It is a word for a sexually undesirable, low-status man, which, of course, really speaks better than almost anything else to the real psychological foundations of Trump’s brand, of Trumpism itself, and of the Trump personality cult. Once you understand that, it is easier to go on to understand why so much Trumpism is expressed in the form of sexual resentment, as in J.D. Vance’s rhetorical forays against childless women, a particularly cruel—and particularly stupid—line of political attack that would be inexplicable without the underlying theme of sexual panic/status panic. The prominence of sexual oddballs in the Trump movement—figures such as the aforementioned Nick Adams and cuckoldry-fetishist Roger Stone, both of them steeped in stereotypical 1970s-era bathhouse sensibilities—is entirely of a piece with that particular flavor of weirdness. There’s more sexual panic in Trumpist immigration rhetoric than there is in Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabines.

And there is a reason that the most powerful Trump-aligned conspiracy theories are almost invariably sexual in nature: the Jeffrey Epstein stuff, the claims that high-ranking Democrats are members of a pedophile ring, etc. J.D. Vance is on the back flap offering his testimonial to the new book from the “Pizzagate” guy—this is the GOP’s offering for vice president in 2024.

Somewhere, Donald Trump is sitting alone in a darkened room, phone in hand, blaring the music from Cats.

Yes, yes, yes. These are some weird dudes.

Super weird.

Words About Words

I did want to write “assless chaps” above, because the phrase, though a cliché, is funnier than “leather chaps.” But the thing about chaps is, they’re pretty much all assless—otherwise, they’re just pants.

But, that aside ...

There ought to be a word for words such as epitome. Maybe there is. I mean words that you learned from reading rather than from conversation, which are words that you often mispronounce the first time you say them in company. On a recent episode of The Dispatch Podcast, Israeli politician Einat Wilf mispronounced the word “epitome,” the same way a lot of people—myself included—do the first time they pronounce it: “eppy-TOME” rather than “a-PITT-o-ME.”

I bring this up not to bust on Wilf, whose accent leads me to believe that English is not her native language. I remember the first time I pronounced the word epitome aloud: It was when talking about the punk band Dissent’s excellent album Epitome of Democracy? I said “eppy-TOME,” too. I suppose an epi-tome might be something that is almost a big book, but that wouldn’t be a very useful word. Tome in the English sense of book comes from the Greek word for a papyrus scroll, and the -tome part of epitome comes from the Greek word meaning to cut. The original sense of the word is abridgment, but it came to mean something more like personification or apex. You can see, kind of, how that would develop: A man whose career is itself a shorthand for excellence is an exemplar of excellence, hence the epitome of excellence in his arena, excellence concentrate.

Sometimes, it’s just the way a word looks. People say “meezled” for misled, lengthen the first vowel in typical, go stray with segue. I made a joke a while back about “radical chic” and “radical chicks,” remembering that I mispronounced chic the first time I came across Tom Wolfe’s famous essay, in a high school English class. (Yeah, it was a good school.) I am sure there are teachers out there who get tired of correcting young people’s pronunciation of fatigue.

Those Greek words ending in -e can be tricky. I had a friend once who told me about discovering the most lovely name, “PENN-loap.” She went on a bit before I asked: “Do you mean Pen-ELL-o-PEE?” Chagrin ensued.

That’s a particular type of person: widely read, narrowly conversed. There’s a whole childhood story in that for many people, me included.

Economics for English Majors

Markets down, markets up! Anxiety!

What the heck is a “yen carry trade”?

As I explained in my Sunday column in the New York Post:

You may have noticed some turbulence in the stock markets last week, and you may have heard a story—an untrue story—that this is a response to a weak employment report.

The jobs numbers weren’t great, but they’re fine.

Last week’s topsy-turvy markets were convulsed largely by exoteric stuff of little relevance to ordinary investors, specifically an interest-rate hike at the Bank of Japan that messed up the “yen carry trade,” an investment strategy based on exploiting differences between interest rates in different countries.

Borrowing in a currency with a lower interest rate to invest in an asset priced in a currency with a higher interest rate is a kinda-sorta form of arbitrage (meaning the exploitation of differences in local prices), though maybe short of the technical definition of the word, as Villanova’s John Sedunov tells CNN:

The yen carry trade proved especially popular in the last four years, because Japan was the only major economy in the world offering essentially free money. (While the US, Europe and others were raising interest rates to fight inflation, Japan has had the opposite problem, and it kept borrowing rates low to encourage economic growth.)

Borrowing for next to nothing and getting a 5% return on a US Treasury sounds like a no-brainer.

“It’s pretty good arbitrage, but it’s not really arbitrage because it’s not risk-free,” said John Sedunov, a finance professor at the Villanova School of Business. “You need to have the exchange rate work in your favor.”

When the Bank of Japan upped interest rates, all those positions based on the difference in interest rates had to come unwound. A carry trade of that sort is a leveraged position, meaning that you’ve invested money that you’ve borrowed, which is fine, within reasonable limits. But leverage is both a profit multiplier and a risk multiplier. Just depends on which way things go.

Elsewhere ...

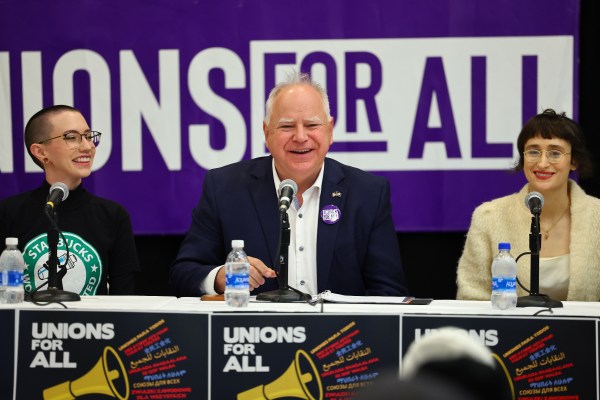

How much difference could one man possibly make to Kamala Harris’s presidential campaign? A great deal, possibly — but not if you’re talking about Tim Walz, the unholy love child of Bernie Sanders and Garrison Keillor who was picked on Tuesday as the would-be veep by the current veep.

No, I’m talking about Jerome Powell.

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

Please subscribe to The Dispatch if you haven’t.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here.

In Conclusion

The fact that Trump and Vance and the rest of those weird dudes are weird dudes is not a license to lie about them. That shouldn’t need to be said, but it does. Tim Walz’s decision to wring a few cheap laughs out of a stupid, dishonest, vulgar lie about J. D. Vance—and I know you know what I am talking about—reflects poorly on his character. Like the much-vaunted “decency” of Joe Biden, Walz’s virtuous-progressive-dad shtick is an angstrom deep.

Because we live in a time of stupid tribal politics, we are expected to think of those who disagree with us not as wrong or misguided or simply in possession of different priorities but as evil, un-American, or, in the word of that book Vance blurbed, unhuman. Because partisans convince themselves that their hatred is righteous rather than vicious, they believe that hurting the people they hate—in any way they can, including by lying—is an exercise in virtue. The despair-inducing part is that it may be the only exercise in virtue available to them.

I have a sneaking suspicion that both true-believing progressives and born-again Trumpists know, in their hearts of hearts, that their political champions are going to disappoint them, that their big policy dreams are not going to be enacted, that they are not going to possess unrivaled power, that they are never going to crush their enemies to the point of powerlessness and irrelevance. That is their dream, but I suspect they know, even if their utopian aspirations were realized to the fullest possible degree, that the result would be disappointing, that there would always be some compromise or insufficiency, and that the victory ultimately would feel hollow. (Which, of course, is true. It is the only wisdom in a lot of these maniacs, deep-buried though it is.)

And so since the Great Thing remains forever out of reach, all that one can do as a practical matter is tell gross lies about J.D. Vance or brandish coffee mugs labeled “Liberal Tears” or make up slanders and circulate them on the Internet, as angry dim partisans such as Matt Bruenig have done with me.

One occasionally hears a confessing Christian say that Jesus’ admonition to turn the other cheek, or the Mosaic prohibition against bearing false witness, are insufficient to our present needs, poorly fitted to our times. I heard people make precisely that argument at NatCon4 in July—that the right must lie and slander and behave dishonestly, because the left will lie and slander and behave dishonestly. Jesus, they will tell you with a straight face, lived in a less hostile culture.

Now Thomas (also known as Didymus), one of the Twelve, was not with the disciples when Jesus came. So the other disciples told him, “We have seen the Lord!”

But he said to them, “Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe.”

A week later his disciples were in the house again, and Thomas was with them. Though the doors were locked, Jesus came and stood among them and said, “Peace be with you!” Then he said to Thomas, “Put your finger here; see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it into my side. Stop doubting and believe.”

Come, friends. Reach out your hands. Touch His wounds, and believe.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.