I’m going to tell you a counterintuitive modern history of American religious liberty. In this true story, Bill Clinton emerges as an underappreciated hero and Antonin Scalia as an unfortunate partial villain. In this true story, conservative Christians have never been more legally free from state censorship, yet they have never felt more isolated and culturally vulnerable. And in this true story, all of the cultural and political dynamics are set in place to make Christians feel more isolated and vulnerable even if they continue to win cases at the Supreme Court.

To understand where we are, it’s necessary to know where we’ve been, and the post-World War II history of religious liberty isn’t so much a story of freedom lost as power lost. The American Protestant church—a church that often proved quite willing to suppress the religious freedom of rival factions (including Catholics)—lost power but gained liberty, and it’s not only deeply unhappy at the outcome but sometimes seems fundamentally unprepared to live in this more-perilous new world.

At the end of World War II, across much of this nation, people of faith enjoyed considerably less liberty than they enjoy today. Protestants, however, weren’t conscious of this reality in large part because they didn’t need liberty. They had power, and nowhere was this power more manifest than in public education. A Protestant school kid would often begin his day with a Bible reading from a Protestant translation of the Bible (typically King James), hear a Protestant prayer from a Protestant school official, and then hear that same message supplemented through Bible classes taught by his individual teacher. In many American jurisdictions, the phrase “public school” meant “Protestant school,” not as an instrument of rigorous theological instruction, but certainly as a powerful tool of cultural formation.

Moreover, this establishment was jealous of its power. Across the nation, dozens of states had passed so-called “Blaine Amendments,” odious pieces of anti-Catholic bigotry that attempted to deny public funds to so-called “sectarian” institutions. These amendments weren’t motivated so much by a desire to separate church and state as a desire to separate Catholic church and state. Catholicism was the “sect” in state legislative sights. Protestants largely weren’t concerned. Their schools were the public schools. “School choice” was hardly even a gleam in the libertarian eye. There was no reason to leave. Public schools were a bedrock institution of American society, and ideas like homeschooling? Well, that was not only a tiny fringe activity, state laws in a number of states made it virtually impossible.

To the extent there was even such a thing as a “religious liberty bar,” the lawyers could hold a convention in a phone booth. They represented America’s smallest religious minorities and America’s oddballs—the guys who smoked peyote to see visions, the people who thought Social Security numbers represented the mark of the beast, and the people who sacrificed chickens to read their entrails.

But then, it all came crashing down. In a series of shocking Supreme Court cases, a progressive court elite destroyed the Protestant public school and ruthlessly disentangled Protestant church and state. School prayers? Gone. Daily Bible reading? Gone. Recitations of the Lord’s Prayer? Gone. Prohibitions on teaching evolution? Gone. The Ten Commandments on school walls? Nope, no longer. In a roughly 20-year span, the edifice of America’s Christian public educational establishment was nuked from orbit.

Suddenly, your community high school wasn’t just prohibiting public prayer, it was so spooked by a generation of legal changes that individual teachers and administrators started blocking Christian clubs from using empty classrooms. They sometimes took Bibles from kids at recess. And these stories spread like wildfire in America’s Christian communities.

College administrators and government lawyers believed that the same Establishment Clause doctrines that had ripped public religious expressions from America’s students also applied to the private religious activities of students on public property. The Establishment Clause imposes limts on government religious expression only, not the religious expression of private citizens. Within a mere quarter-century (a blink of an eye, historically) America’s public school went from actively Christian to (in some jurisdictions) functionally and intentionally anti-religious.

There are those who argue that the modern religious freedom movement is the product of white supremacy, specifically as a means of protecting the so-called “segregation academies” that sprang up across the South during the civil rights era. When the federal government at long last took affirmative steps to desegregate public schools, many members of the Southern white elite created effectively whites-only “Christian schools,” and in the 1970s, the IRS took aim at these academies, seeking to deny tax exemptions to racially discriminatory religious schools. In 1983, the IRS campaign (supported by the Reagan administration) culminated in an 8-1 Supreme Court decision that the IRS could, in fact, revoke the tax exemptions of two racially discriminatory Christian schools—Bob Jones University and Goldsboro Christian School.

While there is no question, then, that racists have use religious liberty arguments to press their white supremacy, the combination of the Bob Jones case and a previous case called Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises (in which the court deemed “patently frivolous” the claim that the owner of a sandwich shop enjoyed a free exercise right to exclude black customers) meant that the religious liberty argument for racial discrimination was largely extinguished more than a generation ago.

I first joined the legal fight for religious liberty in 1991, as a first-year law student, when I volunteered to provide pro bono research. I’ve been continually engaged in legal battle for religious freedom ever since, including litigation groups at the largest religious liberty public interest law firms in the United States, and I’ve never seen even a hint of white supremacy in the effort. Any effort to taint the modern mainstream quest for religious freedom with Bob Jones’s legally discredited past racial malice is simply wrong.

So what did happen as Christian conservatives faced the 1980s? Their lawyers, legislators, and activists faced the task of building a new legal and jurisprudential framework—centered not around the dominance of Christians in the public square but rather on legal equality and viewpoint neutrality. In other words, don’t treat Christianity (or any other religious viewpoint) worse simply because it’s religious.

And thus began a long string of legal and strongly bipartisan statutory victories—interrupted only by Antonin Scalia’s stinging blow.

In 1981, the Supreme Court decided Widmar v. Vincent, and held that a public university could not deny a Christian student group equal access to its facilities.

Three years later, the Equal Access Act passed the Senate 88-11 and the House 337-77. It became law on August 11, 1984. The act prohibited discrimination against religious individuals and organizations in access to school facilities, and it provided protection for student-led and student-initiated religious speech. In 1990, the Supreme Court upheld the Equal Access Act, ruling that its protection of religious speech and expression did not violate the Establishment Clause.

But 1990 wasn’t an entirely good year for religious liberty. On April 17, Justice Antonin Scalia authored a 6-3 opinion in a case called Employment Division v. Smith that transformed (and dramatically relaxed) the First Amendment test that applied when plaintiffs argued that state actions—including state statutes—violated their rights under the Free Exercise Clause. Rather than applying “strict scrutiny” to state action, Scalia wrote that a religious freedom claims would fail when confronted by a “neutral law of general applicability.” In other words, unless the law targets the faithful, it’s presumptively lawful.

At a stroke, the Free Exercise Clause was gutted as an individually potent clause of the First Amendment. Yet almost immediately, Congress acted. In 1993 it passed—and Bill Clinton signed—the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, a statutory attempt to reverse the holding of Employment Division v. Smith. It’s one of the most significant pieces of strongly bipartisan legislation passed in modern American history. It passed the House unanimously and passed the Senate with only three dissenting votes. Clinton happily signed it into law.

In 2000, Congress also happily passed (by unanimous consent) and Clinton happily signed the Religious Land Use and Institutionalize Persons Act, an act designed to supplement RFRA’s protections after the Supreme Court struck down RFRA’s application to state and local government. RLUIPA locked in strong protections for churches and other religious organizations against discrimination by zoning authorities and others who govern land use—allowing churches to plant, grow, and flourish across the nation.

Going into the new century, then, there seemed to be a solid new bipartisan consensus. Prayer by schools was gone, replaced by prayer in schools by students. Religious favoritism was replaced by equal access. The legal and political consensus was so strong, that if you ask me who was the best president for religious freedom, my answer is Bill Clinton. He (and Congress) locked down critical religious freedom protections that still exist today.

So, what happened? Why is religious freedom so contentious? Why do conservative Christians in particular feel that their most precious liberty is under unrelenting assault? The short answer is that America secularized, it polarized, and the nature of the most contentious of the religious freedom cases changed. And thus, even as the legal protections for religious expression held firm (or even expanded), the sense of cultural decline and cultural exclusion has made millions of Christians feel as if they cannot speak their mind and still maintain their jobs, their standing in the community, or the regard of their secular peers.

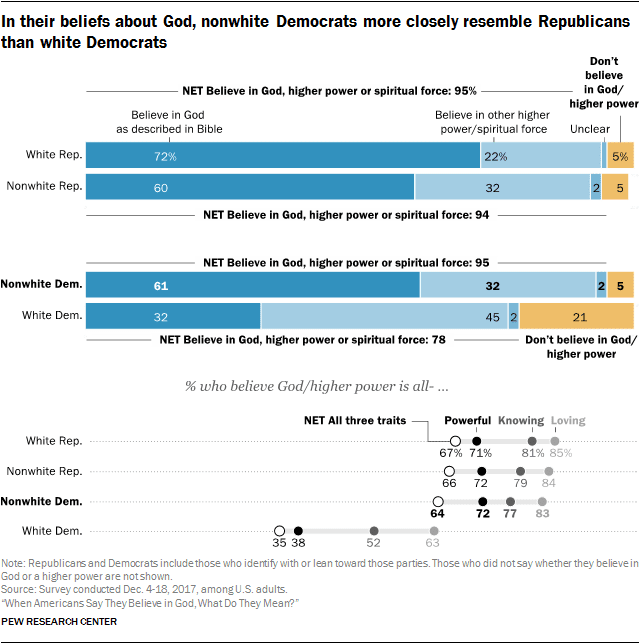

The secularization of the American public is by now a well-established story. But the secularization isn’t evenly distributed across the American political landscape—especially among white voters. Consider this chart, from the Pew Research Center:

It shows a white Republican base that is still overwhelmingly Christian. The white Democratic base is far more secular, and its white spiritual and religious voters believe far less in the God of the Bible. Thus, when a white Christian asserts a legal claim, it’s often perceived not as a “Christian” claim, but rather as a “Republican” claim, and in a time of extraordinarily rising negative polarization, committed Democrats strongly personally dislike Republicans (and committed Republicans have the same dim view of Democrats). It is hard for respect for liberty to survive true enmity.

Moreover, that enmity is compounded by the new nature of contentious religious liberty cases. The days of school administrators or public officials censoring religious expression simply because its religious are largely receding. They’ve been replaced by a series of cases and cultural arguments that center around the sexual revolution and the drive for LGBT rights. In other words, a college may try to throw a Christian student group off campus not because it’s Christian, but because it won’t allow for openly gay leadership. A state may revoke the license of a Christian adoption agency not because it’s Catholic, but rather because it doesn’t place children with same-sex parents.

Thus, the era of the “easy” bipartisan case is largely over. Most progressives would join most conservatives in rejecting a public college rule that flatly prohibited religious organizations from meeting on campus. But most progressives will not join most conservatives in believing that a “discriminatory” religious organization should enjoy equal access. And to make that argument, they point back to Bob Jones and Piggie Park. After all, hasn’t the Supreme Court already ruled that invidious discrimination doesn’t enjoy full First Amendment protection?

But from the conservative Christian perspective, these arguments represent a terrible insult. How dare you compare us to white supremacists How dare you mistake our loving application of God’s word for the hateful exclusion of southern segregationists. We are not defending a malicious fringe that seeks to maintain the badges and incidents of American slavery, but rather the catechisms and core teachings of our churches and schools. Attacking the traditional sexual ethic attacks orthodox Christian theology itself.

So far, progressive arguments haven’t enjoyed a great degree of legal success. To take two key examples, the Supreme Court rejected 9-0 the Obama administration’s effort to apply a federal nondiscrimination statute to ministerial employees. It recently ruled 7-2 in favor of a Christian baker who refused to custom-design a cake for a gay marriage — in large part because state officials expressly condemned the baker’s allegedly discriminatory theology. In fact, conservatives are hard-pressed to locate a truly significant First Amendment loss at the Supreme Court even before Trump’s appointments of Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh. The balance of the case law has tilted very strongly toward liberty.

And yet, there is a strong sense within the conservative Christian church that religious liberty is on the knife’s edge. One election, and it could be lost. But this fear isn’t so much rooted in objective legal fact—the case law is very strong and the most basic doctrines are rooted in larger judicial majorities than many people imagine—but rather in the proper perception of a significantly changed underlying culture. In white progressive-dominated parts of American society (the academy, Silicon Valley, Hollywood, etc.) there is, in fact, a strong antipathy against orthodox Christian views—especially regarding human sexuality. That antipathy does, on occasion, translate into public shaming or even overt economic sanction against conservative Christian voices.

Thus, while conservative Christians largely enjoy liberty from legal sanction, in key American communities they do not have power, and often do not enjoy social acceptance. And, ironically enough, the political and legal actions they take to maintain that liberty—because they are filtered almost exclusively through partisan politics in a polarized age—reinforce the cultural anger that fuels the eventual political risk. And there is no easy way out from the trap. The law of religious liberty has not positively transformed the culture of religious acceptance.

As I look at this dynamic, I think immediately of Yuval Levin’s outstanding cri de coeur against apocalyptic rhetoric Thursday in The Dispatch. A Democratic president isn’t going to bring the Coliseum (yes, that’s an argument I’ve heard from actual conservative intellectuals). Protecting a creative professional’s right to refuse to use his talents to celebrate a gay wedding isn’t the first step on the dark road back to Jim Crow.

But trying to create a “chill the hell out” caucus (in Guy Benson and Mary Katharine Ham’s memorable phrase) will only get us so far. At the end of the day, there is a need not just for legal stability and certainty, but also for Christian courage and conviction. In large parts of American life, it is no longer easy to be a conservative Christian. It carries with it at least some small fraction of the adversity that Christians face in other countries and cultures. We want easy when Christ never promised easy. It’s time to learn to live with (somewhat) hard.

And so, here we are, set to enter a contentious presidential election, with conservatives enjoying rights secured (in part) by Bill Clinton, confronted by challenges empowered (in part) by Antonin Scalia, and no clear way through the impasse. But in the final analysis, with the easy cultural avenues closing all around us, Christians will have to look in the mirror and ask themselves two basic questions. Are we brave enough to faithfully and confidently exercise the liberties that others have won? Or are we too weak and afraid to practice Christianity in the absence of the power we’ve so plainly lost?

Photogaph of protesters in front of the Supreme Court building on the day the court heard Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, December 5, 2017, in Washington, D.C. by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.