Once President Trump started bragging last month that he’d “aced” a cognitive test, it didn’t take long for reporters and pundits to discover the specific test, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Test. Medical professionals, including the test’s creator, Dr. Ziad Nasreddine, pointed out that the test was designed to be a quick screening test of cognitive impairment, “not a sort of intelligence test.”

The test, and the president’s bragging about his answers to specific questions, quickly became fodder for Trump critics and late-night comedians, with Jimmy Fallon saying the president sounded like “someone playing charades after pounding Chardonnay.” Meanwhile, weeks later the Trump campaign is still using it as fodder to question Joe Biden’s mental acuity.

Jokes and campaign ads aside, the test does serve an important purpose for physicians who are dealing with patients who may have undiagnosed cognitive impairments, whether that be dementia, stroke, brain injury, or other conditions.

As summarized by physician Dr. Robert Glatter, in Forbes, it “is designed to assess how we acquire, store, process and retrieve information. It measures things such as basic memory, attention, rudimentary language, delayed recall of objects, and orientation to the date, month, day, place and city.”

Each question on the test looks for something specific that might reveal cognitive impairment, and many of the different sections of the test are abbreviated versions of other, longer tests meant to test different areas of cognition. The test is also used to help determine not only whether the subject has any cognitive impairment, but what might be causing it.

It’s worth looking at the individual components of the text. (Note I am purposefully using an old version of the test as an example, in case anyone who reads this needs to take the test themselves in the future, that their scores will not be artificially inflated by having read the questions ahead of time.)

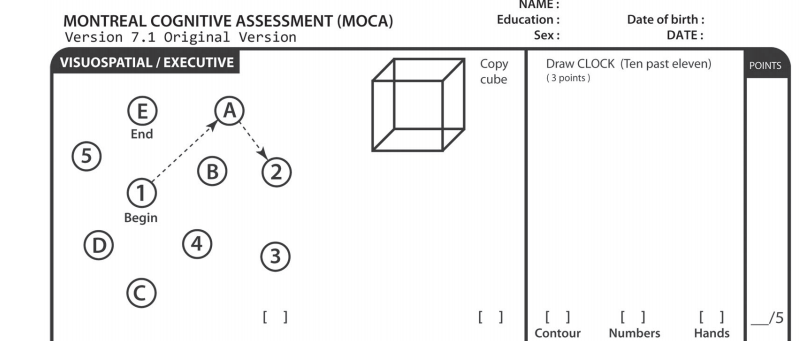

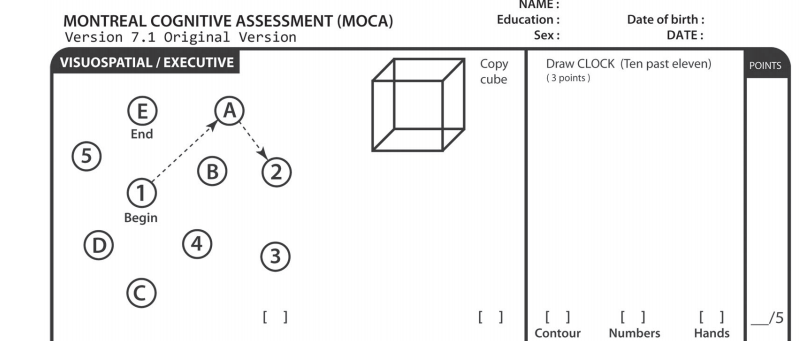

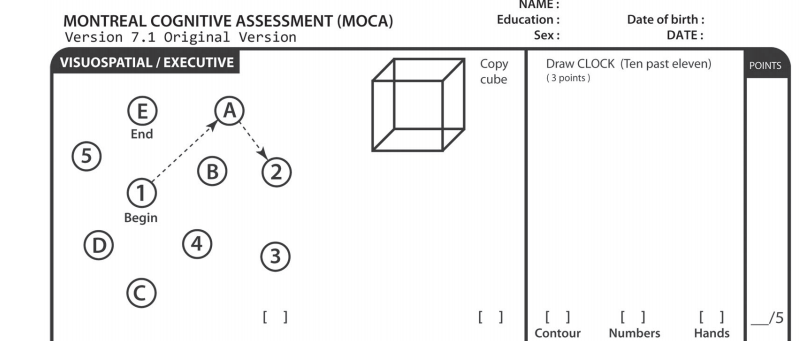

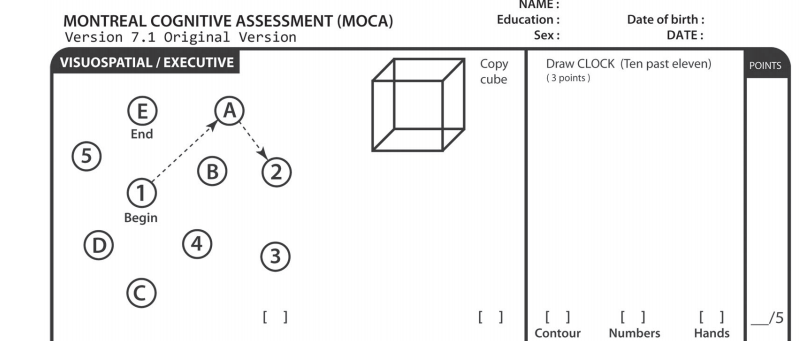

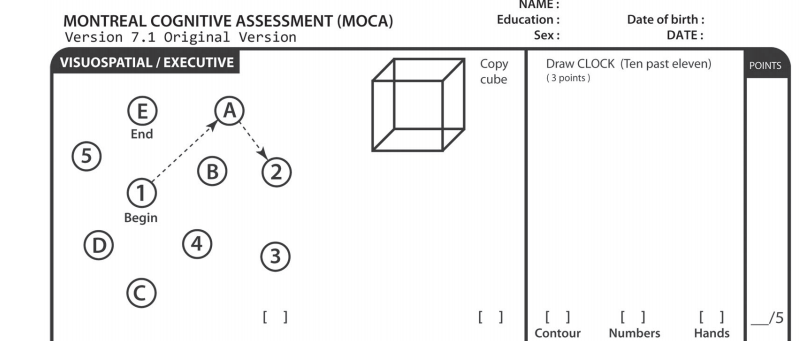

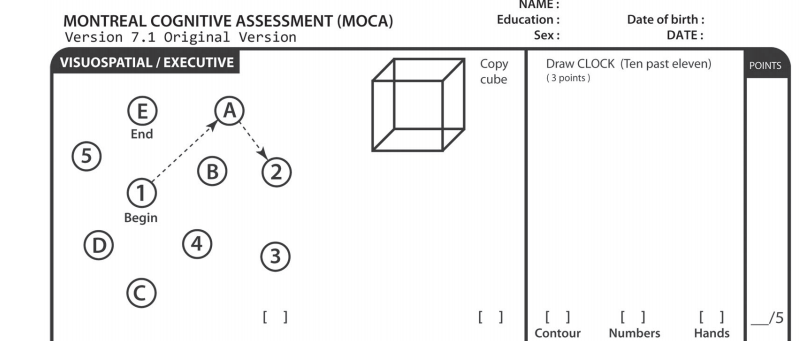

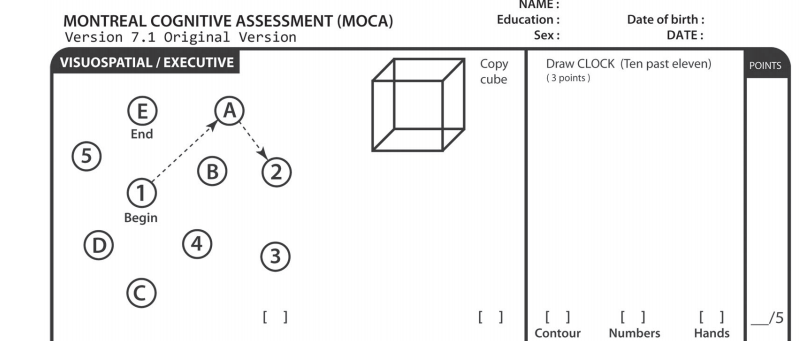

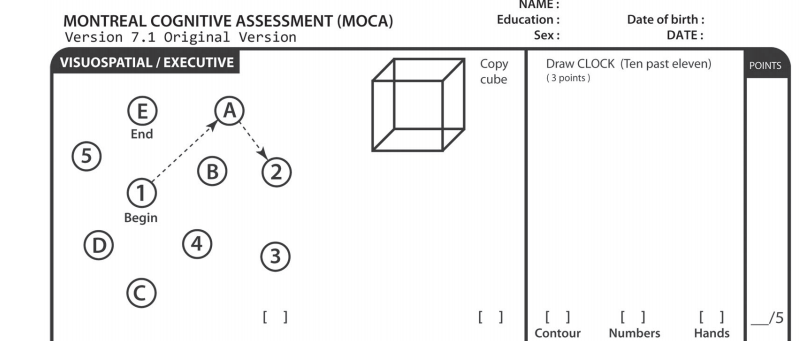

Visuospatial / Executive

This section consists of three different tasks. The Copying test (one point given for correctly copying the figure) and Clock Drawing tests (one point for drawing the overall contour of a clock, one point for arranging the numbers correctly, and one point for “setting” the hands correctly), both test “visuo-spatial functioning,” which encompasses not only understanding what we’re seeing but also the “perception of the size and location of our surroundings.”

Patients who have problems with these functions can fall easily, not recognize familiar objects or faces, misjudge distances, get lost easily, and struggle with driving skills; all issues that can face patients with dementia .

The test involving the letters and numbers is known as the Trails test; the version on the MoCA is a simplified version of the full Trail Making test, which has more letters and numbers, and is timed.

The patient is asked to draw a line from the number “1” to the first letter of the alphabet, “A”, then to number “2”, then the second letter of the alphabet, “B”, and so on. The test also measures the ability to understand images. But it also measures “executive function”; that is, the “set of cognitive processes and mental skills that help an individual plan, monitor, and successfully execute their goals.”

Now, “executive function” in this case doesn’t mean making C-suite decisions for a Fortune 500 company, but more practical tasks like, say, cooking dinner:

Planning and organization: Getting all the ingredients and thinking about the right times to start them cooking so they will be ready at the same time.

Monitoring performance: Checking the food is cooking properly and the water isn’t boiling over.

Flexible thinking: Lowering the heat if the food is cooking too quickly or leaving it longer if it is not cooked.

Multi-tasking: Washing the laundry and putting it out to dry, while still remembering to attend to the food at the right times.”

Notably, a fairly classic clinical vignette of dementia (and one I have encountered in my own work) is a patient being brought to a physician by a family member after burning food (or at times, the actual kitchen) while attempting to cook. While the family member will usually express concerns about the patient’s memory, as a physician I would be concerned about deficits in executive function as well.

In order to score on the Trails Test, the subject must be able to quickly switch between counting numbers and ordering letters, and tests similar skills to what is needed when switching between folding laundry and checking on a boiling pot on the stove. This requires activation of the frontal lobes, and subjects with frontal lobe damage from a stroke, tumor, or brain injury, or with the dementia subtype of “fronto-temporal dementia”, especially have difficulty with this task.

Naming

This fairly simple task involves the subject attempting to name the three animals seen on the page, with one point for each correct answer. (Different versions of the test feature different animals.) While this can be seen as a test of general knowledge, it also screens for a particular deficit called anomia, or difficulty naming objects. Anomia is a form of aphasia, or central language deficit, often described as “word finding difficulty.” It often befalls those who have had strokes, but can occur in some forms of dementia as well.

Memory, Part I

This task asks the subject to repeat back five words that are read to them for the first trial, immediately after they hear the word. This exercise is then repeated for a second trial. This tests a form of short-term memory known as “immediate recall,” but does not actually count for any points; the points are given out only for the “recall after 5 minutes,” which is tested after other components of the test.

Attention

In the first part of the Attention section, the examiner reads a list of five digits, and asks the subject to immediately repeat them. Then, the examiner reads a list of three digits, then asks the subject to immediately repeat them in backward order. This is meant to test both immediate recall and whether the subject was paying attention to the numbers, and failure to do so is often seen in dementia patients, but also those with delirium, such as from a fever.

The second part features the examiner reading a list of letters, and asking the subject to tap a surface every time the letter “A” is read. This task requires the subject to both concentrate and identify the sound of the letter “A”, and NOT respond to other letters, even those that may sound similar such as “K,” “E,” or “O.” A failing score on this item is often associated with traumatic brain injury.

The third part, serial 7s, is meant to measure the ability to perform mathematical calculations without using pen and paper as a cue. This tests different parts of the brain from the parts that test language, and Alzheimer’s patients often struggle with this question.

Language

The first task requires the subject to repeat, word for word, two sentences immediately after the examiner reads them aloud. A point is awarded per correct sentence, but if the repetition is not perfect, if any word is omitted or mistaken, then no points are awarded. Repeating complete sentences is considered to require both an ability to pay attention to and concentrate on the words, and to (albeit briefly) memorize them. The task is more difficult for patients with Alzheimer disease. The second task requires the subject to name, in the course of one minute, as many words as they can think of that begin with one letter (in this case, “F”.) If the subject can name 11 or more words, a point is awarded. This task involves mostly the frontal lobes, and can be impaired by a stroke, or type of dementia called “frontal lobe dementia” or “fronto-parietal dementia” that involves this part of the brain. (A lack of education can also result in failure for these two tasks. Therefore, subjects with less than a 12th grade education are given an extra point to account for this.)

Abstraction

This task asks for subjects to answer the question, “tell me how a ___ and a ____ are alike.” The first question involving a banana and orange, is not scored for points, and if the subject gets it wrong, the examiner will say “they are both fruit.” Then they are asked to compare a train and a bicycle, and a watch and a ruler.

Because this tests not just “semantic knowledge” of what an object is, but requires a level of complex, conceptual thinking, it is often the first task a patient who is suffering cognitive impairment or mild dementia will fail, even if they do well on other tasks.

Delayed Recall (AKA Memory, part II)

In this part of the test, the subject is asked to recall the words they heard earlier in the test, and given a point for each correct answer. If they do not get correct answers, the examiner has the option of testing “cued recall,” first by mentioning the category the word belongs to (for “face”, the subject would be told “this is a part of the body”, and if they still don’t recall, give three options for each word (for “face”, they can be asked “was it nose, face, or hand”).

Although only spontaneous, uncued answers count for points, whether a cue DID help the subject recall the word, or didn’t, can help the examiner differentiate mild cognitive impairment from full-on dementia.

Orientation

The final task is, at first glance, the simplest; asking the patient for the date, month, year, day, and the place or city. And so it is; most patients who score poorly on this part have a significant degree of clinical dementia, with impairment that is already obviously affecting the ability to carry out ADLS (activities of daily living), even without administering the test).

A video of a model patient taking the test can be found here:

An important caveat, however, is that the MoCA, and other cognitive assessment tests, are not definitive instruments for the diagnosis of cognitive impairment, dementia, or a particular dementia syndrome. If someone “fails” the test by scoring less than 26 points out of 30, a primary care doctor would likely refer the patient to a neurologist or perhaps a geriatric psychiatrist for more comprehensive neuro-psychological testing.

Other tests to determine the cause of impairment, such as a brain MRI to rule out stroke, or testing for nutritional deficiencies such as vitamin B12 that can cause general cognitive impairment, are also often needed to make a definite diagnosis.

The MoCA test can help guide physicians through which tests to order. For example, if a patient failed the Trail Making task, a physician may consider a brain MRI to evaluate for frontal lobe damage from a stroke or a tumor. Or, as “pseudo-dementia” from depression can also affect executive function, the physician may wish to screen the patient for depression.

Overall MoCA test scores are also helpful in that they can be used to track the decline of patients by repeating the test on a regular basis (yearly, or possibly more often depending on circumstances). They also provide a simple way for different clinicians seeing the patient to have a general understanding of the cognitive function, by looking at their MoCA scores.

In conclusion, the MoCA test is neither an “intelligence test” nor a test for “dementia,” and “acing” it says little about the subject. It is however a very useful tool for physicians to both screen patients for cognitive impairment, and to give them some indication of the cause.

Photo by Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.