I’ll never have a better job than I did in 2002.

A reserve military intelligence officer who’d just started as a Wall Street law firm associate, I volunteered to return to active duty on September 12, 2001, furious at the attack on my hometown and murder of boyhood friends. Through the kindness of a sympathetic Fordham Law School connection, I obtained a prize assignment to the Joint Staff Directorate of Intelligence to do counterterrorism work.

My duty was to brief the director of intelligence (or “J2”) on terrorism issues at the crack of dawn, before he briefed Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Richard Myers and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. Then I’d answer their follow-up questions in writing, reprise the brief to the National Security Council’s Counterterrorism Security Group via secure teleconference, and go to bed.

This was heady stuff at age 29. Briefing general and flag officers as an Army captain was exciting, but the heart of the job was preparing a PowerPoint slide or two analyzing that day’s best counterterrorism intelligence, which was then blasted out to everyone cleared for top secret/special compartmented information who maintained access to a Joint Worldwide Intelligence Communications System terminal. It was my little contribution to the war effort, for guys and gals serving at the front.

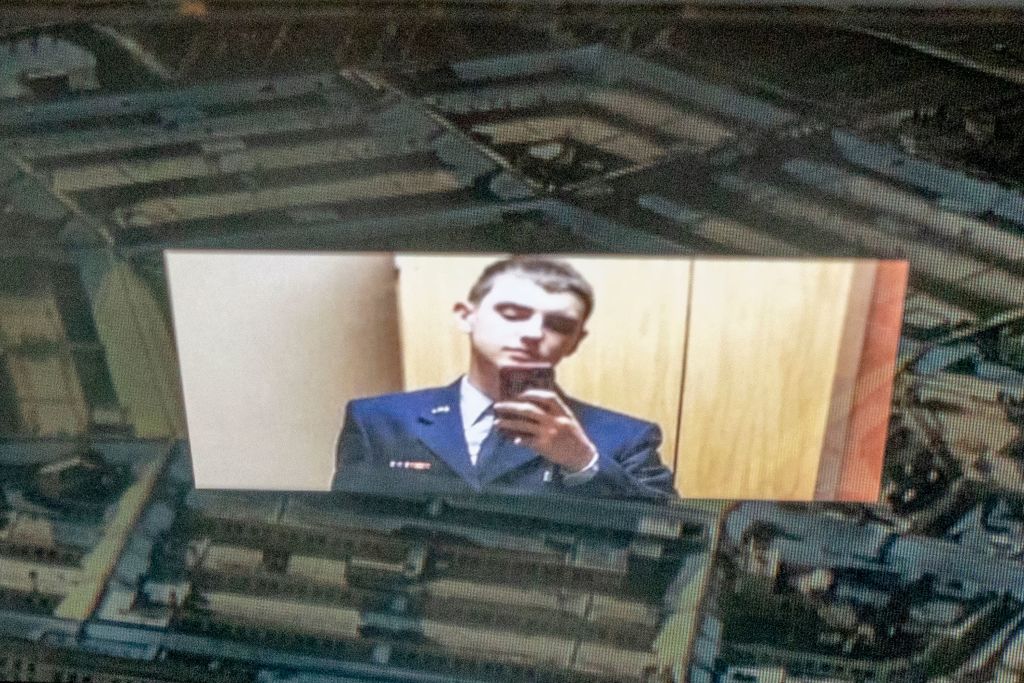

The J2 slides matter, so it was heartbreaking last week to see Airman Jack Teixeira of the Air National Guard arrested on charges of allegedly disseminating my successors’ slides to the online world, including America’s adversaries. I won’t give any possible Benedict Arnold the satisfaction of looking up slides criminally leaked online. But from what I understand from press reports, they reveal the imagery capabilities of National Geospatial Intelligence Agency satellites, the National Security Agency’s codebreaking skills, and worst of all, human intelligence bravely provided by sources to the Central Intelligence Agency.

Make no mistake: Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea are executing countermeasures to defeat our recon birds’ cameras, updating encryption to secure anew their communications, and beating the hell out of anyone they now suspect of spying for the United States.

President Joe Biden’s blithe remark that he is “not concerned” about these leaks was embarrassing given his mishandling of classified information as a senator and vice president, now under investigation by a special counsel—you can bet that the families of men now likely getting tortured in the basement of the KGB’s Lefortovo Prison are concerned. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene’s reflexive defense of Teixeira against the misnamed “Deep State” was appalling, as was Republican legislative leadership’s shamed silence about her remarks. And while former President Donald Trump has not yet weighed in publicly on the matter, his son Donald Trump Jr. has hailed Teixeira as a “hero.”

With senior leaders of both parties so far failing to defend our national interest, what can nonpartisan national security professionals, ideally backed by bipartisan congressional oversight through Capitol Hill’s remaining adults on the armed services and intelligence committees, do to prevent such leaks from happening again? Four suggestions follow.

First, the 9/11 commission appropriately identified Department of Justice-mandated segregation of information within the criminal and national security branches of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and between the FBI and the rest of the intelligence community, as one of several reasons for the government’s collective failure to prevent that attack. Nearly a quarter of a century later, the mantra of information sharing has finally gone too far. A return, not to the artificial “wall” between criminal and intelligence information, but to a healthy respect for the concept of “need to know,” seems overdue. A junior enlisted Air National Guardsman does not need to know too much. Someone such as Teixeira may need to be in the room where classified things happen, but he doesn’t need online access and the ability to print that information.

Second, as many as 1.3 million people are now cleared for top secret information. Too much is enough, and as an initial matter, why are such young enlistees cleared at that level? The Army used to insist that male officers serve a four-year “branch detail” in a combat arm such as armor, artillery, or infantry before embarking upon intelligence work. Similarly the Special Forces were uninterested in a soldier until he’d spent at least four years in uniform, the Ranger Regiment didn’t take first-tour officers, and elite Special Mission Units were filled mostly by men in their 30s. While young servicemembers do dangerous, difficult, and important things for America, we don’t see teenage civilian police officers or FBI agents for good reason: They yet lack mature judgment. By the same token, military intelligence work is not a fit profession for very young people—first let them spend a few years’ apprenticeship carrying a rifle and humping a ruck.

Third, the security clearance process needs to refocus its attention on the rising generations’ particular vulnerabilities. As it stands, the Standard Form 86 Questionnaire for National Security is very well-suited to unmasking members of the German American Bund or the Communist Party USA in the 1940s. Bad guys, for sure, but Charles Lindbergh or Julius Rosenberg are not the biggest threat at present.

Rather, leakers such as Chelsea Manning, Edward Snowden, Reality Winner, Joshua Schulte, and now Teixeira suggest there is a newly perceived type of insider threat. While not entirely divorced from opportunistic exploitation by foreign intelligence services (see, e.g., Snowden), the current threat stems from a worship of transparency for its own sake, dangerously combined with a very “online” culture that developed over the past two generations or so (including my own)..

Fourth and finally, our security services’ efforts at continuous monitoring of clearance holders are obviously insufficient. You give up a measure of privacy when you ask to receive classified information, and we need to look more closely at clearance holders’ online activities. This means routinely scraping open, deep, and dark web sites for their use of classified terminology, as well as racist, antisemitic, or otherwise noxious or extremist propaganda, as reportedly spouted by Teixeira. We need to look more at counterintelligence vulnerabilities posed by Guardsmen and reservists’ private sector jobs, about which the military remains blissfully in the dark. Given the recent arrest of former senior FBI official Charles McGonigal, we need to look at threats posed by some retirees’ jobs as well.

None of this needed change will come naturally to a national security establishment too set in its ways. And especially not to careerist bureaucrats forever wary of “getting in trouble” and jeopardizing their next uniformed or civil service promotion by carefully and thoughtfully walking the fine line between foreign counterintelligence and domestic law enforcement. Nor will it be comfortable to politicians of either party who for ideological reasons lionize criminals such as Snowden or Manning. President Obama inexplicably commuted Manning’s sentence, trivializing an extremely serious offense.

But the American public’s patience has now clearly run out after more than a dozen years’ worth of deadly, serial leaks from malcontents in the military and the intelligence community, an awkward squad who lash out by betraying our country’s deepest secrets to our enemies only because of their personal demons. If current Pentagon and intelligence leaders were corporate executives, shareholders would demand that boards of directors fire them and insist upon independent outside investigations, just to avoid civil liability for their repeated failures to successfully implement basic compliance programs.

To regain Americans’ trust, our uniformed, security, and intelligence services quickly need to adapt to unpleasant new realities.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.