Donald Trump attacked the Federal Reserve throughout his presidency, complaining about interest-rate increases and lobbing insults at Chairman Jerome Powell. In his bid to regain the office, he has renewed those attacks while demanding that as president he get a direct say in setting interest rates, though he has partially backed off from that statement.

Trump has every reason to be worried about the Fed: If he follows through on his campaign promises of across-the-board tariffs and large tax cuts, the result would be upward pressure on inflation that would force the Federal Reserve to set interest rates higher than they otherwise would have been. Fortunately, the Federal Reserve’s independence makes it unlikely that Trump will succeed in his plans were he to win another term. Unfortunately, “unlikely” is not as reassuring as “impossible” when talking about America’s most functional and important economic institution. Moreover, the most worrying possibility is that Trump would simply be initiating what could be the beginning of the end of the Fed as we know it—a process that could be completed by his successors from either party.

A brief history of presidents and the Federal Reserve.

Most presidents would prefer lower interest rates to higher ones, no surprise given the evidence that mortgage rates have a big effect on how people feel about the economy and the president’s handling of it. As a real estate developer, Trump probably believes in low interest rates even more.

Up until what is known as the Fed-Treasury Accord in 1951 the president, through the Treasury, did have a say in setting interest rates. This may have made sense in World War II and its immediate aftermath when financial repression—keeping interest rates artificially low—helped the federal government finance a historically unprecedented amount of borrowing. Presidents have had no formal say in setting interest rates since then, but many of them have tried, in some cases with success, to affect them.

Lyndon Johnson pushed privately for a reprise of World War II-style financial repression, reportedly complaining to Fed Chairman William McChesney Martin, “My boys are dying in Vietnam, and you won’t print the money I need.” Richard Nixon cheekily said, “I respect his independence. However, I hope that, independently, he will conclude that my views are the ones that should be followed”—and his Fed chairman, Arthur Burns, obliged, contributing to a sustained inflation that did not come to an end until it was tackled by Fed Chairman Paul Volcker in the early 1980s—facing some criticism from Ronald Reagan in the process. George H.W. Bush and his economic team repeatedly blamed the Fed for what at the time seemed like a slow economic recovery that killed his reelection in 1992 (the growth and jobs data have since been revised up).

In 1993 Bill Clinton wisely adopted a strict policy that neither he nor anyone else in his administration would comment on the Federal Reserve. This policy had the economic benefit of reducing some of the uncertainty and confusion in financial markets that stemmed from Bush’s public criticisms of the Fed. It also had the political benefit of making it easier for administration officials to avoid having to insert themselves into contentious debates: Instead they could just refer to Clinton’s “no comment” posture. George W. Bush and Barack Obama both continued the policy. It has also been followed assiduously by Joe Biden, even as the Fed aggressively raised interest rates and kept them high during his presidential campaign and even while falling inflation led other major central banks to start cutting their rates (the Fed did cut rates in September).

Donald Trump will have a strong motive to restrain the Fed.

Trump was an exception to the norm of respecting the independence of the Fed established by Clinton. I was just several feet away from Powell at the Fed’s Jackson Hole conference in 2019 when Trump tweeted, “My only question is, who is our bigger enemy, Jay Powell or Chairman Xi?”—the most colorful of the many public criticisms, and a particularly notable one because the Fed had just cut rates to about 2.1 percent. Trump also failed to reappoint Janet Yellen as Fed chair, breaking from the tradition of reappointing the choice of one’s predecessor from the opposite party—something that was done by Reagan, Clinton, Bush, Obama, and most recently by Biden. It was not a big deal, especially since Powell was a perfectly good replacement, but it represented a small step in the wrong direction of politicizing the Fed. More worryingly, Trump reportedly came close to firing Powell—and only backed off due to a combination of stock market and legal concerns.

While Trump did not fire Powell and his Fed appointments were mainstream and generally excellent, we should not be overly optimistic about what might happen if he returned to the White House.

The trend within Trump’s term was not promising. Gary Cohn, his first director of the National Economic Council (NEC), constantly restrained him, but he was replaced by Larry Kudlow, who did less to push back on the president’s whims. Trump announced his intent to nominate Steve Moore to the Fed, someone whose qualifications were much stronger in terms of partisan politics—raising money for Republicans and demonstrating fealty to Trump—than the Fed’s tradition of nonpartisan expertise. Moore’s nomination was never formally advanced when a firestorm of objections to his personal conduct made it clear he could not be confirmed. Trump did nominate Judy Shelton, who is deeply non-mainstream, including supporting a return to the gold standard that almost all economists agree would dramatically destabilize the economy. Her nomination was ultimately blocked by Republican Sen. Pat Toomey, among others. Moore and Shelton could be a starting point for the Fed in a second Trump term, especially if his advisers are more enablers than restrainers.

Moreover, if Trump were to follow through on his policy pledges, they would be much more inflationary than his first-term plans. He has already proposed well more than $5 trillion in net tax cuts, possibly as much as $10 trillion, and if he has a Republican Congress he will probably be able to get a substantial fraction of that enacted. This would put upward pressure on inflation, which would lead the Fed to either raise interest rates or slow or halt the cutting process.

Trump’s proposals for 10 to 20 percent tariffs on all $4 trillion of imports, plus 60 percent tariffs on China, dwarf anything he did in his first term. The tariffs would translate into higher prices, causing a notable jump in inflation while also reducing output and raising unemployment principally by raising the price of intermediate goods used in manufacturing and also shrinking exports. This would leave the Fed with a quandary. It could ignore what would hopefully be only a one-time jump in the price level but not a permanent change to the inflation rate while perhaps even cutting interest rates to offset the hit to the economy. More likely, however, the Fed would be forced to raise interest rates because the reinflation would come just on the heels of the current inflationary episode and would risk getting embedded into expectations and wage-price persistence, something the Fed could not afford to allow to happen.

Given the near-record debt relative to the size of the economy, high interest rates would compound the problem of fiscal management, which itself could lead to even higher interest rates if needed to support the additional borrowing. This is perhaps the most common reason governments around the world have put pressure on their central banks, something economists call “fiscal dominance.” Moreover, the combination of higher tariffs and higher interest rates would put upward pressure on the dollar (although this pressure could be offset by increased sovereign risk)—which would go the opposite of the direction of what Trump and Vance propose, giving them another reason to press for their preferred monetary policy.

But could Donald Trump do anything?

Trump clearly would have the desire to do something about the Fed, but the Federal Reserve is protected by numerous features that keep it independent from presidential meddling. Interest rates are set by a committee of 12 voting members, known as the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Seven of these are governors who are nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate to staggered 14-year terms. The other five are drawn from the 12 presidents of the regional Federal Reserve banks (the New York Fed has a permanent seat and the others rotate) who are appointed by their own boards. I have not the slightest doubt in the integrity of every one who is currently on the FOMC and could not see any of them following the dictates of Biden, Trump, Harris, or any other president.

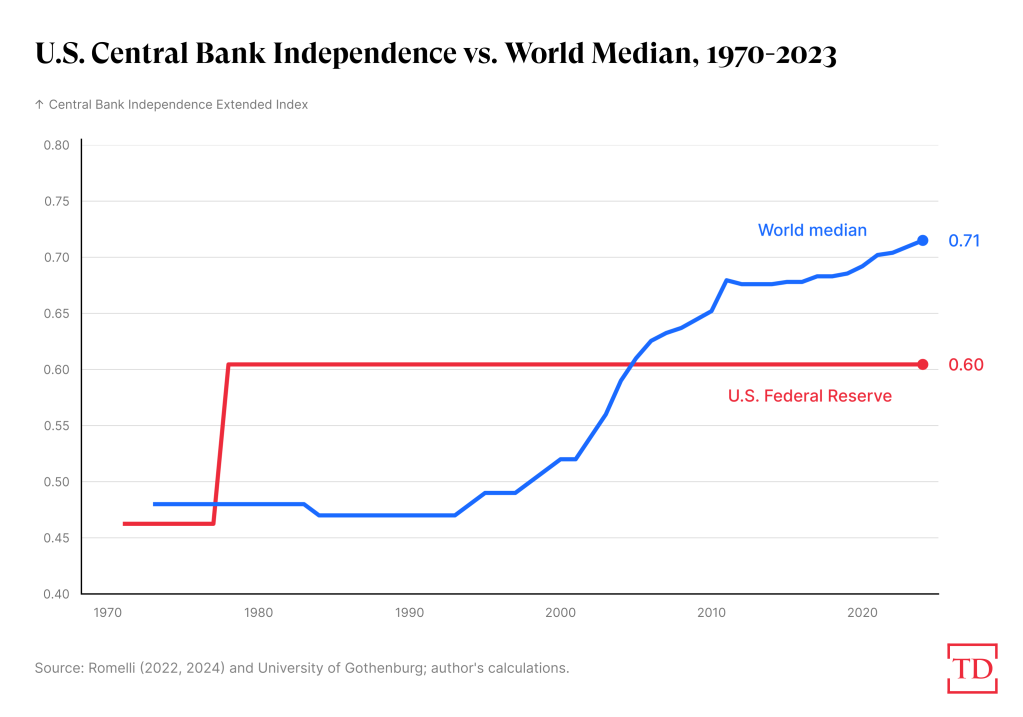

But the Fed’s independence is not absolute. Over the last several decades, country after country has passed new laws to strengthen the independence of their central banks. The Fed was, de jure, among the more independent central banks in 1980 but today is in the bottom half according to one leading ranking (other academic rankings tell a similar story).

Two of the biggest demerits for the United States in the ratings: The chair has a renewable four-year term, while the European Central Bank—which is the world’s leader in de jure independence—is led by someone with an eight-year non-renewable term. Perhaps more serious is the legal ambiguity about whether the Fed chair can be removed without cause—or could challenge his or her removal.

Trump’s conditional support for Powell while implicitly continuing to claim the power to remove him is not completely reassuring: “I would let him serve it out especially if I thought he was doing the right thing.” He could decide to fire Powell as chair, though that decision would probably end up in the Supreme Court and there are conflicting opinions on how it would rule. Regardless, Powell’s term as chair ends in May 2026, and Trump would very likely try to replace him with a loyalist, perhaps even with someone who committed to reflecting Trump’s voice in the FOMC. Historically the chair guides the direction of monetary policy, but hopefully a more extreme choice would be unable to get the support of the rest of the committee. (The only governor terms that expire during the next presidential term are Adriana Kugler and Jerome Powell.)

But “hopefully” may not be enough, and even the attempts to meddle with the Fed would increase uncertainty and risk raising risk premiums, lowering the stock market, and ultimately reducing economic growth. If the system holds, however, none of those effects would be huge.

Would it be the beginning of the end of the Fed?

But what if Trump’s changes were the beginning of something more sustained? If Trump had a successor who shared his views, they would be able to replace at least two more governors in the following four years—and more if others followed general historical practice and did not finish out their full terms.*

Moreover, the erosion of norms can turn into an arms race. Biden’s Fed appointments have been mainstream, including his reappointment of Powell—a Republican—as chair. But what if Trump were reelected and put highly partisan hacks on the Fed? My hope would be that a future Democratic president would go back to the norm of nonpartisan experts, but it could also lead the president to appoint his or her own partisan hacks in order to not be the sucker who followed a broken tradition. The result would be a Fed that looked more like so many of the other “independent” agencies in Washington, D.C.—staffed by partisans without deep expertise, prone to wild swings in policy between administrations, and lacking broad-based legitimacy.

Independent central banks are the closest thing to a free lunch macroeconomists have to offer. Decades of research has documented how independent central banks can achieve lower and more stable inflation and less severe business cycles without any worsening in unemployment or growth on average. People may not agree with every decision the Fed makes—I know I do not—but the alternative of having presidents or the Congress set rates with their high levels of present bias and low levels of expertise would be much, much worse.

Correction, September 26, 2024: This piece originally misstated the number of governors the president would be able to appoint.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.