DUBOIS, Pennsylvania—Terry Noble raised more than a few eyebrows in this conservative community when he and two other local Democratic activists pooled personal money, rented a vacant store-front along bustling Brady Street, and opened a field office to boost support for Kamala Harris and her running mate, Tim Walz.

“DuBois For Harris/Walz,” blares the large sign over the makeshift Democratic headquarters— affiliated neither with the vice president’s campaign nor the state party. Dubois is a town of roughly 7,400 in Clearfield County, a rural, central Pennsylvania enclave that backed Donald Trump over Joe Biden in 2020 73.9 percent to 24.5 percent. So it’s not surprising at least some voters might wince at the unexpected sight of grassroots support for the Democratic ticket, or that they might take issue with the framing of the signage.

“We created a bit of a firestorm in the community. People didn’t like the term ‘DuBois For Harris/Walz,’” Noble told The Dispatch this month, during an interview at the Harris outpost that sits across the street from the DuBois Public Library. “I would guesstimate about 30 percent of the people that, when they’re stopped [in traffic] and look here, I get some kind of a negative reaction, including, ‘Let’s go Brandon,’ or whatever the conspiracy du jour is.”

Noble, a former Pennsylvania Democratic Party official and founder of its Rural Caucus, has had a front-row seat to the political realignment that has transformed counties like his from blue, or at least competitive, to ruby red. In Clearfield, the shift happened with the 2010 midterms that saw Republicans win a historic majority in the House of Representatives. Prior to that, Clearfield County leaned Republican, but Democrats were competitive—approximately 52 percent to 48 percent on average, is how Noble describes it. In any event, he is hardly naive about the politics of his county.

But Noble is hopeful his DuBois field office, and the work of volunteers there, might shave just enough of Trump’s 50 percentage point margin in Clearfield County four years ago to help push Harris to a narrow win in the toss-up Keystone State.

Noble’s “DuBois For Harris” sign has gotten some positive response from locals as they’re driving by or idling at the stoplight. “I would say, I get about 15 percent of the people—thumbs up, honking the horn—2-1, right? Right in our margin,” he said. To bolster his case for the vice president with any undecided or inquisitive voters that might pass by the office on Brady Street, Noble and his cohorts have taped on the windows statements from prominent Republicans who are either sharply critical of Trump, such as former Vice President Mike Pence, those or endorsing Harris, such as former Vice President Dick Cheney.

Throughout Pennsylvania, The Dispatch heard hopeful stories like this from Democratic activists, door-to-door canvassers, and party officials during a week of reporting in what could be the most pivotal of the seven battleground states on the 2024 map. Enthusiasm spiked almost immediately after Harris replaced Biden as the Democratic nominee in late July and has not abated. Grassroots volunteers continue to flood county party headquarters and Harris campaign field offices, attendance at Democratic events delivers near Trump-size crowds, and rank-and-file Democratic voters have coalesced behind their nominee in a way they had not before Biden withdrew.

But the Republican insiders The Dispatch spoke with across Pennsylvania last week offered similarly rosy anecdotes, projecting almost unwavering confidence that victory was at hand. Spend some time in the heart of the less populated, “T” of Pennsylvania—the regions other than greater Philadelphia and Pittsburgh—and it’s easier to understand why Republicans there sound convinced Trump is going to outperform the polling.

Yard signs can be misleading, but the farther one travels into Pennsylvania’s interior, rural counties, the more common the public support of Trump in small towns, along highways, on front lawns, and on acres of farmland appears. Bob Gleason, chairman of the Pennsylvania Republican Party during 2016, said this year’s support for Trump reminds him of that election, when he squeaked out a 48.2 percent to 47.5 percent victory over Democrat Hillary Clinton. Results reversed in 2020, when Biden topped the former president 50 percent to 48.8 percent (a fact Gleason doesn’t argue with).

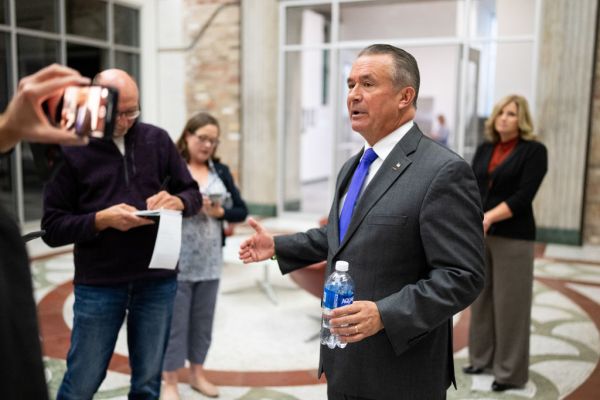

“You never know about elections, but I’m feeling much better than I did in ‘20 about this,” Gleason said over lunch in Johnstown. It’s the largest city in Cambria County, a former Democratic stronghold that recently saw the GOP take the lead among registered voters. “I think turnout will be better this time for Trump.”

“If you registered to be a Republican now, you’re going to vote. We don’t have to worry about you going to vote,” added Gleason, who is still a member of the state GOP. According to state figures, Democrats lead Republicans among registered voters in Pennsylvania by 312,725, down from an advantage of 516,794 four years ago. Gleason acknowledged the race is close but predicted Trump would outpace Harris by as many as 3 to 4 percentage points. “It’s trending towards [Trump,] it really is,” he said.

Sam DeMarco, the GOP chairman in solidly Democratic Allegheny County, displayed the same sort of bravado a couple of days earlier in Pittsburgh. “Trump has the edge. You go back to 2016 and 2020, the polls both underestimated his support both times,” said DeMarco, an at-large member of the Allegheny County Council. “Kamala Harris is an empty suit, and that’s to be charitable.”

“Trump’s been running for eight years, there’s nothing new that’s going to come out about him, that’s baked,” DeMarco added. “But a lot of people don’t know who Kamala Harris is.”

The race for the White House, dependent on the outcome in battlegrounds like Pennsylvania, has been close from the outset, with polling available to offer solace to partisans on both sides of the Harris-Trump divide.

Still, the surveys showing the former president closing in on the vice president, or taking the lead, seem more numerous with less than one month before Election Day. That dynamic of a surging Trump and nervous Democrats—who felt more confident about the contest after the September 20 presidential debate—was dominating the political discussion three weeks before November 5. Yet Harris is still drawing big crowds, has more money to spend, and has fielded a superior voter turnout operation.

Indeed, Democrats from one end of Pennsylvania described themselves in interviews as “cautiously optimistic.” They concede Trump could win. But when asked to explain the reasoning behind that blunt concession, the Democratic insiders we spoke with blamed the memory of Trump’s surprise win in 2016—a sort of political post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Biden would have lost Pennsylvania,” said Mike Veon, a grizzled Democratic operative in Pittsburgh and former party leader in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, explaining that Harris’ entry into the race made the race competitive. But Veon added: “She’s 2, 3 points on average up, and I think even in the internal stuff, that is true. But my sense is, understanding all that, looking at the history of the state and I guess being scarred by 2016 in a very significant way, I still think there is a Trump turnout factor that we have to account for.”

“I still would rather be us than them, I really would, even though I say it’s a coin flip,” Veon said.

Democratic door knockers emphasize that 2024 appears much different to them than 2016—chiefly the positive responses they’re getting from their own voters about Harris, compared to the tepid support for, if not outright opposition to, Clinton they heard in 2016. Eight years ago, Democrats canvassing for Clinton here encountered another problem that turned out to be fatal: strategic arrogance from the Clinton campaign that hampered their voter turnout efforts. It’s been the opposite from Team Harris this time around.

The vice president may lose, but it won’t be for lack of excitement or grassroots participation from her own party—or from self-sabotage.

“The reality when we got out there—when people were out—is that there were a lot of people who were Democrats who had heard [a] quarter-century of attacks on Hillary Clinton and we needed to be there reassuring them much earlier than I think the campaign had prepared for,” Matt Munsey, the Democratic chairman in Northampton County, said during an interview at an expansive field office in Easton. “That was a sign.” Trump carried Northampton County by nearly 4 points in 2016; Biden won it by just under 1 point.

“There has been a lot of excitement since the day after [Biden] dropped out and said, ‘It’s her,’” Munsey added. “There’s just been huge enthusiasm and I feel like it’s been building.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.