Hey,

Every career involves learning some lessons the hard way. I actually think you could do a fun symposium or essay series called “Lessons Learned the Hard Way.” I’m sure every experienced person has a story to back up their advice, from the lion tamer (“make sure you start when they’re young”) to the Hezbollah communications equipment procurement guy (“check your supply chain closely”).

I bring this up for a bunch of reasons (this “news”letter promises to be a bit of a ride). One lesson I learned the hard way: There are a lot of different kinds of libertarians.

I don’t want to go too far down memory lane, or too deep down rabbit holes, but the gist is that a long time ago I got into fights with some small but often very loud and cranky libertarian sects, and I made the mistake of accepting that they spoke for libertarians generally. This was very unfair to a lot of libertarians who have very different views. For years after, a lot of normal, sane, decent, libertarians were still pissed at me for things I said about “libertarians” that really only applied to, say, the Ron Paul or Lew Rockwell crowd.

It was a good reminder that many who claim to speak authoritatively for an idea or group are, in fact, simply trying to steal the intellectual or moral authority of a label. Not everyone who insists they are speaking for a group is telling you the truth, even if they think they are. Not all self-described feminist leaders speak authoritatively for women. There are lots of people who claim to be spokespersons for Christianity, Judaism, conservatism, progressivism, etc. who are in fact just pushing a narrow agenda.

But the relevant lesson I learned: There are many different kinds of libertarians, a point I promise to return to.

I should note that all broad ideological and religious groups have really weird internal sectarian battle lines that are largely invisible to people outside the fishbowl. I don’t know much about the schism between the Missouri Synod Lutherans and the Evangelical Lutheran Church, but I know it’s a thing. I can tell you a lot about the fault lines within intellectual conservatism. Some tribes get along just fine with each other. Some do not. But what we all know, to one extent or another, are the shibboleths and ideological lodestars that separate us. But these dividing lines are often invisible to outsiders.

The left used to have the best schisms. Most non-communists couldn’t tell you the difference between Mikhail Bakunin and Karl Marx, but boy oh boy, their acolytes hated each other. Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, Trotskyites and Stalinists, Eurocommunists versus Soviet Communists, the Lovestoneites versus the Ruthenbergians, it goes on and on. That’s why the “People’s Front of Judea versus the Judean Peoples’ Front” thing is so funny.

My favorite schism is probably the Hatfield-McCoy-esque battle between The Amalgamated Order of Real Bearded Santas and the Red Suit Society chronicled by This American Life.

You’re probably asking yourself about now, “Did I leave the stove on?” You also might be asking why I’m saying all this. Well, first, because I love this stuff.

Also, I think the narcissism of small differences is among the most important, and definitely one the most interesting, drivers of political and cultural conflict. Also, I think the most interesting arguments are between groups that generally agree on first principles but differ wildly on where they go with their disagreements. These arguments are interesting because they revolve around the hard cases, where principles are in conflict and difficult choices are necessary. Arguments between capitalists and communists can be entertaining, but they rarely get far past the starting line. Debates between, say, foreign policy neoconservatives and conservative realists, Social Democrats and socialists, Russian Orthodox Christians and Catholics, Sunni and Shiites, AORB Santas and RSS Santas go way down the racetrack before they fight for the checkered flag.

But the main reason I point all this out is that I need to ease into the argument I’m going to make. So, let’s get back to libertarians.

As I said, there are many, many, rooms in the mansion of libertarianism. This intellectual diversity is uniquely interesting because many libertarians deny this, claiming that libertarianism is a clear and perfectly consistent philosophy. In 2001 I got into a spat with Harry Browne, the 2000 Libertarian Party presidential candidate, on this very point. Browne argued that libertarians are “consistently on one side on every issue,” which is a weird thing to say for someone who spent so much time with libertarians.

There are left-libertarians and right-libertarians. There are libertarians who call themselves conservatives and there are conservatives who call themselves libertarians. The gang at Reason is not the same kind of libertarian crowd as the one at the Mises Institute. Even among the subgroups there are divisions. I guarantee that the good folks at Cato have arguments in the lunchroom from time to time. Many people think Randians are libertarians, but Ayn Rand emphatically didn’t—and even if many Randians identify as libertarian, their leaders often take after their founding mother and score poorly on “Plays well with others.” And Friedrich Hayek, often considered the patron saint of libertarianism, did not call himself one (he was a lovable “Old Whig”). Meanwhile, the Libertarian Party of New Hampshire is a dumpster fire that, from what I can tell, no decent libertarian wants to be associated with. Its Twitter account recently posted, “Anyone who murders Kamala Harris would be an American hero.” Hell, there’s been a decades-long simmering libertarian civil war over … the Civil War.

So let’s put aside the ideological definitions for a moment and talk about personality types.

I am a longtime critic of using psychology to explain ideological positions. Jonathan Haidt has moved me off some of my more strident views in this regard, but I still think a lot of psychological explanations for political disagreements are invidious borderline phrenology-level garbage.

Yet, I think it’s true that some people do come to their ideological commitments via their personality or psychology. Some radicals really are simply the kind of people who want to see the world burn. Some conservatives are just natural curmudgeons. Some progressives (and conservatives!) just think the world should be “good” and they don’t really care about the arguments or the trade-offs that come with pursuing their goals.

But there is a kind of libertarian whom we used to call “left-brained” (though the whole left-brain right-brain thing is basically a myth). Today we might say some of them are “high-functioning” but “on the spectrum” (I don’t mean this as pejorative—some of the most brilliant and decent people I’ve ever met fit this description). We all know the type, and if you don’t it’s very possible that you are the type. They’re extremely logical and categorical in their thinking. They are impatient with the messiness of emotions and interpersonal dynamics. They are often blunt in a way that is indistinguishable from arrogance. I think it’s fair to say that these people, mostly men, are overrepresented in fields like engineering. By no means are they all socially awkward or “spectrum-y,” but they all love to follow “the data” and “maximize efficiency.”

I have no idea if there’s any data on how they are distributed ideologically, but in my experience a lot of them are really into economics, particularly free market economics, for the same reason some people are naturally in love with mathematics. Complete and rational metaphysical systems external to ourselves have a kind of religious pull for some people. In their youth they often have a heavy Ayn Rand phase because Randianism extols individual achievement and efficiency without regard to the feelings of the masses.

Let me tell you a quick true story. Twenty years ago, I used to debate libertarians a lot. One of my most popular debate partners (I’ll leave his name out of it), was a great guy (and I’m he sure still is). We’d have fun debating privatizing lighthouses and all the rest. It became an annual affair with beers and laughs from the audience. Then the last time we did it, the debate fell flat. My opponent had switched careers from journalism to finance. And in the process, his outlook changed. He went from touting the brilliance of the invisible hand to believing that the hand of the state needed simply to impose efficiencies the political process was too dumb, lazy, or corrupt to impose. He wanted a libertarian monarch or national CEO of sorts to cut through the red tape and the political dysfunction.

Indeed, a more mainstream version of this thinking can be found in the unkillable idea that the government should be “run like a business.” I don’t have time to explain (again) why, but the simple fact is you can’t run government like a business because it isn’t one. (And it really shouldn’t be!) Anyway, the point of the story is that my libertarian sparring partner was, in many of the ways that matter most, no longer a libertarian. He was better described as a technocrat who understood that libertarians are right in theory but not up to the job in practice.

This sub-group of libertarians tends to reduce man to homo economicus, a purely rational economic actor. Now, the history of the term homo economicus is more complicated than you might think. John Stuart Mill, who coined the phrase, did not believe that man was simply “economic man.” He said that the field of political economy treated men as purely rational maximizers of economic advantage. But he emphatically did not believe that political economy was the sole or even best lens to look through. Adam Smith and Friedrich Hayek definitely did not subscribe to the idea that man is just homo economicus. But critics of Smith, Hayek, and their ideological followers liked to pretend otherwise. The truth is that Marxism, not capitalism, comes much closer to the cult of homo economicus.

Indeed, it would not surprise me in the slightest if, in the 19th century, the personality types I’m talking about were attracted to socialism or Marxism for similar reasons they are attracted to libertarianism today. After all, there was a time when “scientific socialism” had the frisson of gnostic heresy and metaphysical truth these guys find so seductive. I know enough about the Progressive Era and the New Deal to be highly confident many of those championing technocratic rule by “disinterested experts” found the concept of “disinterestedness” conveniently congenial with their personality types: “People like me should be in charge.”

For instance, Stuart Chase, the intellectual often credited with coining the phrase “the New Deal,” once said, “I speak in dispraise of dusty learning, and in disparagement of the historical technique.” Chase wanted an “economic dictatorship” run by people like him. “Are our plans wrong? Who knows? Can we tell from reading history? Hardly.” In his book, The New Deal, he asked, “Why should Russians have all the fun of remaking [the] world?”

Today, there are a bunch of so-called libertarians who are equally ebullient about remaking the world. They see things like Artificial Intelligence as a kind of Philosopher’s Stone capable of transmogrifying the world. And they might be right!

The problem is that they are not what you might call “natural libertarians” so much as “natural John Galts.” Their attraction to free markets and economic efficiency comes from a different place than a love for liberty qua liberty. For most, you’d never know it because they’ve become acculturated into libertarianism and they work in institutions where there’s no material temptation or incentive to move off of their ideological, cultural, and political commitments. Even if they might be tempted, a free market economist at a university or think tank doesn’t get a lot of offers to be part of an authoritarian intellectual junta. They don’t get invitations or see opportunities to become oligarchs.

But some see exactly that opportunity. Right now.

I don’t entirely trust all of the reporting on the tech billionaires flocking to Trump. I’m not questioning any journalist’s integrity, I just know enough about some of the players—and enough about how ideological outsiders miss important nuances and context when reporting from outside the fishbowl—that I am open to the idea things are more complex than the reporting suggests. (I have never read a story about any institution I’ve been part of that adequately captured the internal dynamics of that institution.)

Still, it seems obvious that a bunch of very rich people, who once described themselves as libertarians, have concluded that libertarianism won’t get the job done. Peter Thiel, a youthful fan of Ayn Rand, was once a libertarian hero. He championed the idea of man-made floating city-states in the middle of the ocean that would be a kind of maritime Galt’s Gulch. The idea was “to establish permanent, autonomous ocean communities to enable experimentation and innovation with diverse social, political, and legal systems.” During Covid, one such project in the Caribbean was launched and Thiel proclaimed, “The nature of government is about to change at a very fundamental level.”

Whatever you make of that stuff—I think it has some appeal despite its Bond villain vibe—it appears that the super-investor has hedged his bets. Rather than put all of his eggs on some Randian Casablanca in international waters, he’s also investing in domestic American politics, and perhaps changing American government at a very fundamental level. A while back, Thiel struck up a friendship with Curtis Yarvin, the dashboard saint of the “neo-reactionary” or “Dark Enlightenment” movement, which considers liberal democracy a failure. (If you’ve read Suicide of the West, you know that I am completely and passionately on the opposite side of that project.)

This is exactly one of those places where I think a little skepticism and humility is in order. I have no idea if Thiel fully subscribes to Yarvin’s lust for “techno-monarchy.” I know other intellectuals in Thiel’s orbit who definitely don’t. Rich intellectuals—and Thiel is certainly rich and an intellectual—often collect weird people they find amusing or interesting. (I was once invited to have dinner with Thiel myself, though I don’t think I made much of an impression). But we know that Thiel and his circle have made investments in Donald Trump. I have a friend who’s followed Thiel closely for years. His theory is that Thiel doesn’t want to be an American oligarch, but Thiel has reluctantly concluded that oligarchy is inevitable and it’s better to be an oligarch in an oligarchy than not. Again, I don’t know if that’s true. But I don’t know that it’s not, either.

And Thiel is hardly alone. Elon Musk, another spectrum-y, hyper-intelligent, libertarianish John Galt type, has clearly made a huge bet on Trump.

This is already very long. So I’ll stop offering examples of other Silicon Valley techno-libertarians and crypto bros who have decided that Trump is their best option. From everything I’ve heard and read, it seems clear that none of these people think Trump is one of them. They think they can use him, bribe him, herd him. It’s not an unreasonable bet. Trump has already reversed himself completely on TikTok and crypto-currencies—even idiotically talking about paying off the national debt with crypto currency.

What I want to close with is the intellectual fallacy at the heart of this stuff. I keep hearing about people in this crowd talking about how liberal democracy is an impediment to their cornucopian vision of technological revolution, that AI is too important to leave to voters, Congress, and the courts. I get it. If Thanos’ gauntlet or the genie’s lamp is just over the horizon, why put up with committees and politicians who might get in the way?

Contrary to the Dark Enlightenment bong-session fantasies about moving beyond liberal democracy—which includes the rule of law, natural rights, etc.—there is nothing beyond liberal democracy. It’s the summit. Its precepts, as Calvin Coolidge and Francis Fukuyama argued, are final and cannot be improved upon. It’s the edge of the map, and like those old medieval maps said: Beyond, there be monsters. This isn’t some goody-goody, patriotic, Enlightenment chauvinism. It’s certainly true that it’s better to be an oligarch in an oligarchy. But oligarchy is bad. Moreover, oligarchy is not a new idea. It’s a very old one. It’s one of the oldest ideas humans have. And the problems with it—which are way too numerous to detail here—stem from the very thing the “efficiency maximizers” and would-be John Galts don’t like about politics in the first place. Human nature cannot be repealed; it can only be channeled and harnessed to productive and moral ends.

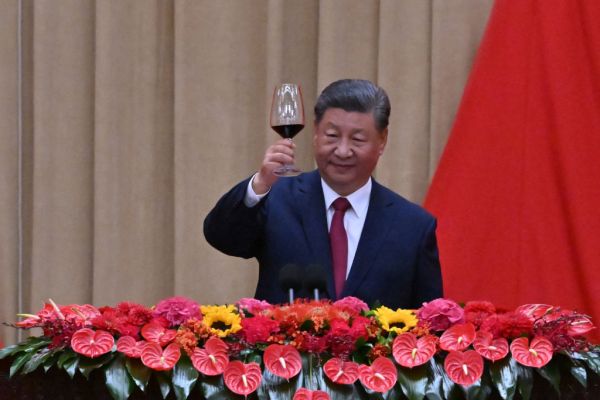

To use language this crowd likes, liberal democracy is antifragile and scalable. It provides avenues and mechanisms for self-correction and adaptation. Yes, it can become sclerotic and dysfunctional, but the solutions—literally the solvents—that clear the arteries is liberal democracy itself. The hubris of the techno-monarchists or techno-oligarchs is that with the right technology, which was made possible by liberal democracy in the first place, you won’t need the system that made it possible. They point to China as proof I’m wrong. But I look to China as proof I’m right. Whatever problems we have, I’d rather have our problems than China’s.

The new technocrats, like the old technocrats, think the solution to political problems is more data. But the kind of data they have in mind is merely the epiphenomenon, the dye marker of homo economicus’ maneuvering. The phenomenon of the human spirit is something more. Just as man does not live by bread alone (even at affordable prices), experts cannot rule by data alone. The kind of system they hint at, or perhaps lust for, is a machine that is seductively beautiful on the drawing board. Engineers love machines and they can make them do amazing things. But the machine of human society has a ghost in it, the human spirit. And it is folly to think that engineers can master that sustainably at scale, to use their terms.

Monarchy is a kind of monopoly on political power. It “worked” when humanity was largely illiterate and unliberated. When enough of humanity was liberated from ignorance, monarchy’s monopoly was unsustainable because it was inadequate to the task of stifling innovation and human agency. That’s not going to change with more data and better computing power.

Actual libertarians understand this. Lovers of systems of pure logic who call themselves libertarians don’t.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.