Now that we’ve had a couple weeks to digest the 2024 presidential election, it’s as good a time as any to examine how U.S. trade policy might change during a second Trump term—and what’d happen to the U.S. and global economies as a result. What follows is not simply me screaming “ABANDON ALL HOPE YE WHO ENTER HERE” 500 times but is instead my best, most sober guess—the usual caveats about staffing and events notwithstanding—for how a future Trump administration and global market players will try to balance the once-and-future U.S. president’s, ahem, unique affection for tariffs with their own economic and geopolitical realities. In general, yes, things will get worse and more costly—but they probably won’t be as bad as the worst-case scenarios lay out because markets will adapt and in some ways are much better prepared to adjust to however the DJT wrecking ball smacks into the global economy. The bigger and scarier question, however, is what happens after they do.

(This is gonna be pretty long, so if you already read Capitolism a lot, great job and please feel free to skip the first section.)

A Quick Recap of Trump 1.0

The best way to understand Trump 2.0 is to start with Trump 1.0. To keep things moving (and to avoid my PTSD flaring up), I’ll briefly summarize the biggest moves, but you can dig through past Capitolisms for much (much) more.

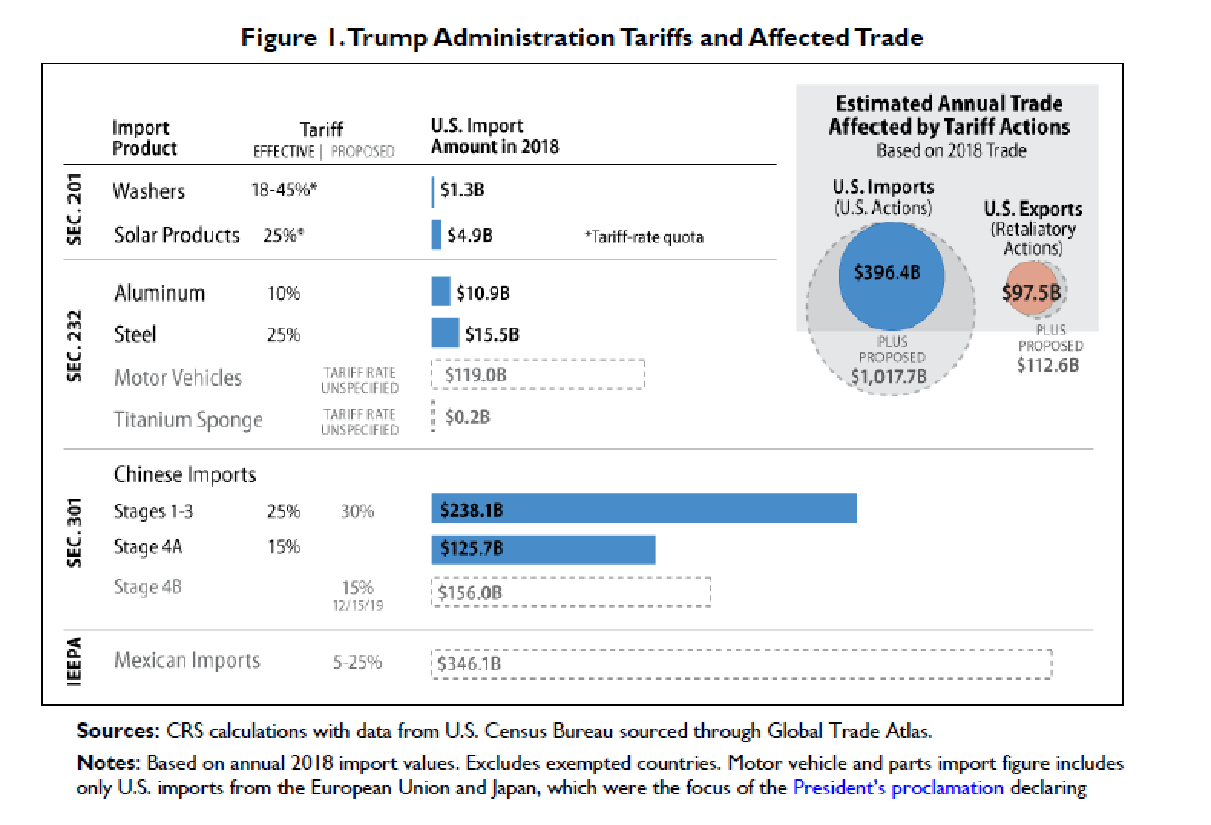

First came the tariffs. Beginning in 2018, Donald Trump unilaterally launched three types of tariff measures: 1) global “safeguards” on washing machines and solar products; 2) global “national security” tariffs on steel and aluminum; and 3) “Section 301” tariffs on an escalating amount of Chinese goods. By 2019, approximately 15 percent of all stuff imported to the U.S. were subject to these measures. Trump also threatened other tariffs—on cars, all Mexican imports, and a few other things—that were never implemented. This handy CRS chart summarizes the situation as of mid-2019:

The new tariffs prompted a flurry of activity by governments and companies trying to avoid the tariffs, either by securing an up-front exemption so that the country/product wouldn’t be covered or by applying for a temporary exclusion after the tariffs were imposed. On the latter, companies filed tens of thousands of exclusion requests, some of which were successful (at least for a while). A few companies also managed to get their products out of the tariffs entirely, and a few governments agreed to swap tariffs for equally restrictive quotas. Many other governments (China, the EU, Canada, Mexico, India, Russia, Turkey), however, retaliated against U.S. exports—especially U.S. farm goods, which led the administration to give U.S. farmers about $20 billion in “emergency” subsidies to offset their losses.

On trade agreements, the Trump administration’s moves ranged from very bad to mundane to comically weird. The most notable agreements were the terribly named U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which basically added some liberalizing (e.g., digital trade) and some protectionist (automotive “rules of origin,” labor/environmental policing, etc.) terms to a copy-and-pasted NAFTA; Trump’s Phase One deal with China, which has since (predictably) fallen apart; and a narrow deal with Japan that gave U.S. farmers essentially the same market access they would’ve had if Trump hadn’t foolishly abandoned the completed Trans-Pacific Partnership. The administration also initiated more traditional trade agreement talks with the U.K. and Kenya, but these never went far and were basically shelved by the Biden team. There also were a flurry of insignificant mini-deals (or, in the case of Europe, pretend mini deals) that—as trade expert Samuel Marc Lowe detailed in a recent piece—governments used to get out of Trump’s crosshairs. (One particularly silly deal, Lowe later reminded me, was this groundbreaking Lobster-for-Lighters deal, also with the EU.) At the World Trade Organization, Trump was mostly disinterested in negotiations and shut down the organization’s appellate body—both bad moves but ones that don’t have major or direct economic effects.

Beyond these things, Trump also leaned into Buy American restrictions, frequently jawboned companies that had the audacity to consider investing abroad, and dabbled in industrial policy, particularly near the end of his term.

Overall, the Trump 1.0 approach was not only a big break from freer-market Republican trade policy, but also a significant departure from a decades-long, bipartisan White House approach to trade—one that avoided major trade wars and coupled relatively narrow protectionism with reciprocal trade agreements that generally opened markets here and abroad. Trump 1.0 also was messy, piecemeal, incoherent, and often reverse-engineered by frantic bureaucrats trying to make U.S. policy match whatever thing Trump happened to tweet out that day. And it was all intensely political: With deals and exceptions affecting billions of dollars in trade and numerous companies’ financial futures, lobbying on trade issues skyrocketed—as did the repeated appearance of impropriety:

Thanks to several years of perspective, moreover, we also know—as numerous Capitolisms have documented—that Trump’s novel approach to trade policy wasn’t particularly effective: The tariffs and related chaos imposed relatively high costs with relatively little to show for it. On the other hand, the policy also wasn’t as devastating as some folks (not me, for the record) predicted. As bad as the policies and uncertainty were, goods trade is a small part of our giant, services-oriented U.S. economy, which was at that time being bolstered by a business cycle on the upswing and good Trump-era economic policy (tax reform, regulatory prudence, etc.). Companies and governments also diligently worked to avoid tariffs, retaliation, and spiraling trade wars, using every legal mechanism they had at their disposal.

This time around, however, things could be different—for better and worse.

How It Could Be Worse—Much Worse

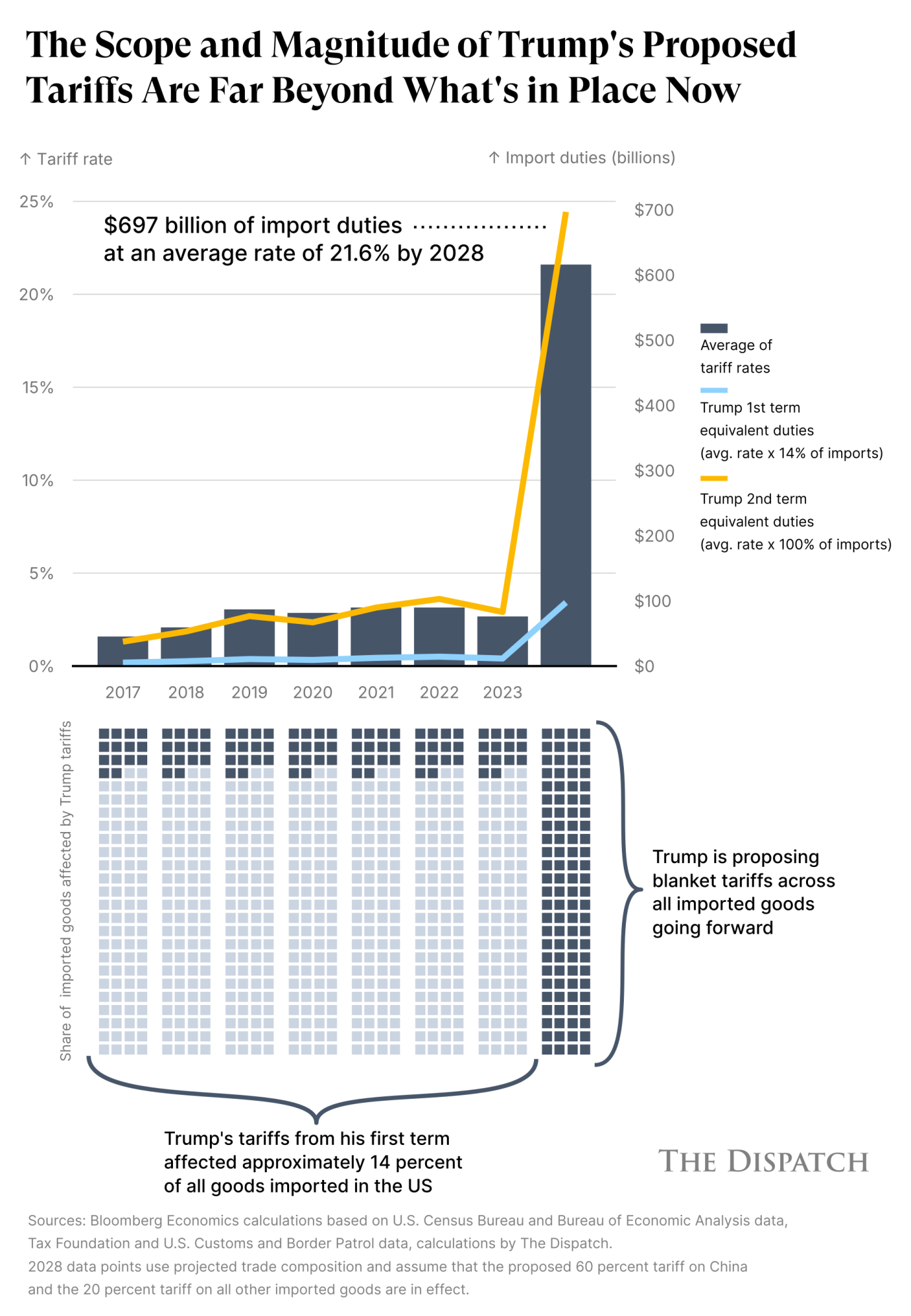

Donald Trump has repeatedly promised much higher and broader tariffs than he implemented last time around. Most notably, he wants 60 percent tariffs on all Chinese imports, instead of the current 15 percent to 25 percent on around half of them, plus a new 10 percent to 20 percent tariff “ring” on all imports from all other countries. Leaving aside other assorted tariff threats (on Mexican EVs, for example), the “Full Trump” would thus move U.S. tariff coverage from about 15 percent to 100 percent of U.S. goods imports, and it would send the average U.S. tariff rate from around 3 percent to more than 21 percent—a level higher than the “Smoot-Hawley” tariffs that deepened the Great Depression.

The economic cost of such taxes would be unsurprisingly significant—far greater than the net costs of Trump 1.0 tariffs and far more disruptive. Respectable economists have uniformly found that the Full Trump would substantially raise prices for U.S. companies and consumers (up to $3,900 per household) and act as a significant drag on the economy overall. Particularly painful for consumers would be necessities—like certain fruits or shoes—that, even with tariffs, still won’t be made here in significant volumes. Similar costs would be borne by U.S. companies—e.g., foreign-owned manufacturers that import proprietary inputs from affiliates abroad—that can’t quickly and easily (if at all) move their entire supply chains to the United States. Retailers and wholesalers would, of course, suffer too.

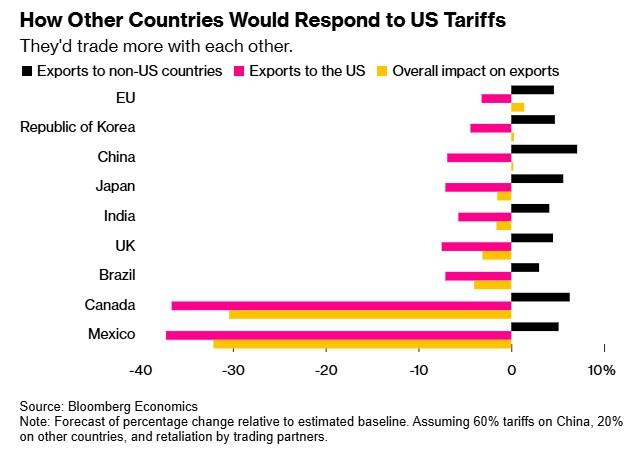

As shown in the table above, retaliation from foreign governments against U.S. exports or investments would add to the economic pain, and—based on experience during Trump 1.0 and recent statements from officials in China, Europe, Canada, and Mexico—we should expect many (but not all) governments to pull the trigger in response to new U.S. tariffs. From there, it’s really anyone’s guess as to how the tit-for-tat game ends, although the short answer for the U.S. economy and global trading system would be “not great, Bob.”

I do not, however, expect this worst-case scenario to unfold—at least not right away and according to plan—for several reasons. For starters, a massive tariff action early in Trump’s presidency would rattle the stock market, which Trump has long seen as a symbol of his economic stewardship and is apparently why Trump is reluctant to pick tariff-loving Bob Lighthizer—the U.S. trade rep from 2017 to 2021—for treasury secretary (insert smallest violin here). It also wouldn’t make political or economic sense for the Trump administration, propelled into the White House by inflation-weary voters, to turn around and start taxing coffee, bananas, energy, and other not-made-here necessities on Day 1. (Tariffs on petroleum products would not just increase gas prices but also hurt some of Trump’s friends in the oil industry, given the global nature of fossil fuels trade.)

I expect other products would also be exempted from any blanket tariffs, no doubt thanks in part to heavy lobbying from foreign governments and affected companies (both foreign and domestic). For example, high tariffs on Chinese-assembled smartphones would not only upset millions of American consumers but also hurt American national champion Apple (which, despite years of supply chain diversification, still makes many iPhones in China) and help its main foreign rival Samsung, which makes most of its phones in Vietnam. Global tariffs on things like semiconductor manufacturing equipment would hobble the federal government’s tech ambitions (and help China). And tariffing all imports from FTA partner countries, which have effectively zeroed out their tariffs on U.S. goods, would be similarly odd for a president who (supposedly) cares so much about “reciprocity.”

Finally, there may be a desire in both the White House and Congress for at least some of the tariffs to be implemented legislatively—a move that would make the new taxes more durable and would partially offset revenue losses that accompany an extension of the Trump tax cuts, thus helping the tax bill meet “reconciliation” requirements that ease would its passage. At the very least, you’d think Trump would want to see how congressional tax talks are progressing before he got bored and just tariffed everything himself.

It thus seems more likely that, instead of the Full Trump, we get something less—but still much bigger than what we have now. Higher tariffs on most Chinese goods, for example, seem all but certain to arrive quickly. Given how much Trump campaigned on global and reciprocal tariffs, moreover, we should probably expect some form of a broader U.S. tariff regime, whether unilateral (more likely) or legislative (less), but with significant to-be-determined carveouts for FTA partners and essential goods. And both measures will likely be accompanied by another process for securing tariff exclusions, at least temporarily.

Even this watered-down system, however, would come with significant economic costs—and many more implementation problems than a blanket tariff would produce. Prices of certain goods would rise, as many companies are already warning; U.S. manufacturers would suffer from higher input costs and lower exports; import-reliant retailers and wholesalers would take a big hit to their bottom lines; and domestic investment would be stunted. Foreign governments will retaliate against not just American goods but maybe services, investment, or intellectual property too; and some that held off on retaliating last time might do so now because, given Biden’s failure (or refusal) to get U.S. tariff policy back on its pre-Trump course, they see no point in trying to wait the U.S. out this time around.

Broader tariffs would also mean fewer opportunities for supply chain workarounds like those that boomed in response to Trump’s first round of China tariffs, and presumably far more requests for tariff exclusions—music to Beltway lobbyists’ ears. And bigger tariffs would make it harder for U.S. companies to simply absorb the costs (like many did last time), or for the U.S. dollar to appreciate enough—and for foreign currencies to weaken enough—to offset the tariff hit (though the dollar would get stronger).

Still, these harms don’t guarantee a recession for reasons already stated (and because the economy’s in pretty good shape today). On the other hand, we should expect a bigger aggregate shock than Trump 1.0, especially because government budgets are more stressed, prices are much higher, and no major tax-cut rocket fuel is on the horizon. And, as trade economist Kim Clausing just explained, corporate tariff avoidance, compliance, and lobbying has its own costs, too.

Finally, investment-sapping uncertainty and chaos would once again reign (in fact, it already is), especially after markets and governments respond to Trump’s opening salvo and then Trump responds to that. It’s in this second stage of Trump 2.0 where things are potentially much scarier and certainly less clear. For example, would another post-tariff explosion in duty-free, direct-to-consumer shipments or other lawful (and unlawful) attempts to avoid tariffs cause Trump or Congress to boost tariff enforcement and related bureaucracy? Would a dramatic appreciation of the U.S. dollar amplify current Trumpworld calls to weaken the greenback? Would a strong market selloff in response to bigger-than-expected tariffs have the same calming effect on a second-term Donald Trump who’s no longer burdened with reelection concerns? What happens if Trump imposes tariffs and his mortal enemy, the U.S. trade deficit, refuses to budge (as economics teaches us)? Super tariffs? Currency controls?

It’s going to be a long four years for trade wonks. At least all the lobbyists (and D.C. steakhouses) will be happy.

On the Bright Side …

On the other hand, there are a few reasons to expect things to be better this time around, at least in certain ways.

For starters, Trump might actually improve on some of the worst, non-tariff aspects of the very bad (and, it turns out, very futile) Biden trade policy. For example, the U.S. might end Biden’s total moratorium on comprehensive trade agreements (though with libs in charge in the U.K., the most obvious target may be off the table). The Trump administration will probably also be better on the booming area of digital trade, which the Biden team ignored for progressive, anti-Big Tech reasons and despite a massive U.S. advantage internationally. Trump might also wisely put the final nail in the coffin for global “tax harmonization” efforts and might even be better on some non-tariff barriers like dumb FDA regulations on baby formula and other items or even maybe the Jones Act (no, really).

The second silver lining is that both businesses and governments are far more prepared to handle whatever Trump throws at them this time around. As Bloomberg reported a couple weeks ago, Trump probably isn’t bluffing when it comes to costly new tariffs, but “senior bankers say privately that companies and policymakers around the world are confident they learned how to deal with Trump and his trade wars during his first term.” For governments, this includes both retaliatory sticks and some easy-to-swallow carrots, such as mini-deals of the type we saw last time—minor concessions or stuff they were going to do anyway, but enough to give Trump the victorious headlines he craves and to allow him to move on to other targets. Energy-starved South Korea, for example, is reportedly planning to commit to buying more U.S. petroleum products (which it needs anyway) and to trumpet new investments in the U.S. manufacturing sector (which were already happening). Smart moves!

Companies, meanwhile, say they’ve also have been planning for future trade disruptions in several ways. First, they’ll front-run any new tariffs and stockpile needed imports:

“Ryan Petersen, CEO of freight forwarder Flexport, said customers in the past have prepared for increased tariffs by stockpiling goods.” “That’s happened every time there have been new tariffs announced. You see this bubble of goods moving in ahead of time,” Petersen said.

Recent spikes in U.S. import data, in fact, indicate that some of this activity has already begun. And because even Trump tariffs take weeks or even months to implement, you can bet U.S. importers will be ready to ship even more into the country when new tariffs are first announced but before they take effect.

Second, Trump 1.0 and the pandemic have pushed companies to develop a more diverse supplier base to adapt in response to tariffs targeting a single country like China or Mexico:

Steven Conine, co-chairman of Wayfair, said on an earnings conference call Nov. 1 that the online furniture retailer views the potential tariff hikes as “very navigable.” Conine said its marketplace model enables it to source from a range of suppliers and make swaps when necessary. He said Wayfair also has been working with suppliers so it doesn’t depend as much on single sources of materials and parts. “We certainly have some practice now navigating tariffs,” Conine said.

Wayfair certainly isn’t alone in this regard, and overall there’s a lot more flexibility in the system today. As Stanley Black & Decker CEO Donald Allan Jr. told analysts recently, the company has been planning since the spring for “a Trump victory and a new tariff regime” and has a “playbook on the shelf ready to go.” That playbook, he added, includes diversified sourcing and some highly telegraphed price increases. But Allan also made clear that the plan doesn’t include bringing onshoring production here because, even with tariffs, “it’s just not cost effective to do.” Many other company officials have said much the same thing, while others have indicated they might onshore production at “significantly higher” costs “if customers are willing to pay a premium” (or, more accurately, are forced to).

In the end, none of these workarounds will be costless for companies and American consumers. Having more sourcing options, carrying more inventory, changing shipping strategies, lobbying for exclusions, and other tariff mitigation efforts are surely more expensive than a world without the measures. And Americans will bear these and uncertainty costs somehow, whether via higher prices, less hiring or investment, lower stock values, or lower economic growth. But that pain is still better than an alternative world in which the full costs of tariffs are simply endured and passed on.

The third and final “bright side” is one for the global economy but not necessarily the United States (at least not directly): Regardless of what Donald Trump does over the next few years, everyone else appears unwilling to embrace costly economic isolationism and will instead just move on without us. Much like the supply chain moves, in fact, these shifts have been going on for a while. As I explain in the introduction to our new Cato book on globalization, the United States has abandoned trade agreements, but most other governments continue to negotiate and abide by them: There are about 370 deals in force as of mid-2024 with no sign of a forthcoming reversal. Washington’s inaction, along with an increasingly risky U.S. market, have also pushed smaller governments in Asia and Latin America toward an eager China seeking economic friends for the coming trade wars (here’s a brand new example). China is, in fact, preparing for Trump 2.0 by unilaterally liberalizing trade and investment with other countries that might also soon face higher U.S. tariffs. (They did this last time too.)

These and other moves reflect an economic reality that many in the United States seem unwilling to acknowledge: The U.S. economy is big, but the global economy is much bigger. Companies and governments want to do business here, but they have alternatives and will look elsewhere if it’s in their economic and geopolitical interests to do so. The Financial Times recently noted, in fact, that global shipping stocks didn’t sink on the Trump election news because “[t]he US is a sizeable, rather than giant, tassel in the global trade tapestry,” accounting for just 5 percent of global seaborne imports by tonnage. (Bilateral U.S.-China trade accounts for just 1.4 percent.) “Trump’s last experiment with tariffs,” meanwhile, “ended up clipping global seaborne trade — measured in tonnes/km — by only 0.5 percent.” Economists Sherman Robinson and Karen Thiefelder, meanwhile, have projected that foreign exporters won’t respond to future U.S. tariffs by lowering their prices (to maintain U.S. market share) because, “In a world economy where the US accounts for only 10% of global trade and potentially rival trade bloc[s] have emerged in Europe and E&SE Asia, the US is no longer hegemonic in global markets.”

In this modern world, U.S. isolationism will likely be matched not by global isolationism but by simply everyone else moving on. Thus, Robinson and Thiefelder project that a U.S.-China trade war would cause “a dramatic fall in bilateral trade,” but also that other countries would expand their trade with these and other nations. Overall, they “find that the world economy can adjust to US trade wars, diverting trade around the US.” Bloomberg’s economics team just projected much the same thing: “Other countries will offset most of their lost trade with the US simply by trading more with each other. That points to the possibility that globalization could keep on humming — just without the US at its center.”

Again, this doesn’t mean that Trump 2.0 will be costless for the global economy—Bloomberg sees a 7.5 percent drop in world trade if the full tariffs are implemented—but it does mean that, even with big U.S. tariffs, the world won’t abandon trade and fall into another Great Depression. Nobody wants that, maybe not even Donald Trump.

Summing It All Up

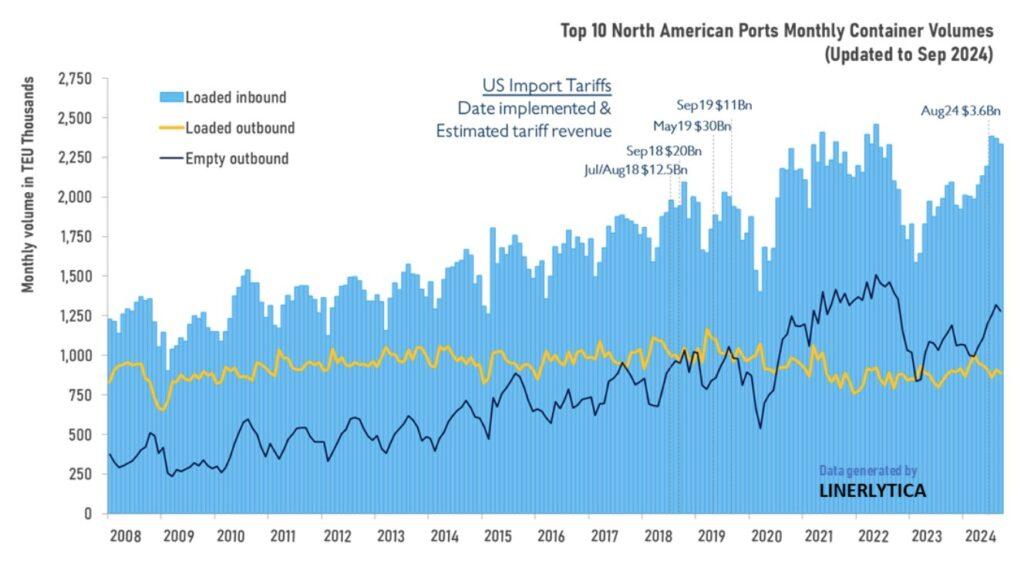

In lectures to students, I often try to explain that the global economy today is like a river and trade is like water: You can throw lots of stuff—natural or man-made—into the river and make a big mess, but the water will quickly adjust to flow around it. This analogy isn’t perfect because rivers flow only one way, but I think it still makes the general point well. Over the last few years, we’ve seen various trade and investment restrictions imposed all around the world, yet trade, supply chains, and globalization keep finding ways around these rocks. As I noted in my book intro, for example, inflation-adjusted goods imports are up substantially since the Trump 1.0 trade wars began. Container volumes have increased too:

And despite all the talk of “deglobalization,” the latest DHL Global Connectedness index, which aggregates global flows of trade, capital, information, and people flows, remained this year right around the record high it set in 2022 (even though, at just 25 percent, the world is far from fully integrated).

The risk, of course, is that Trump 2.0 is so cataclysmic that globalization—and the seismic demands of billions of people who want to engage in long-distance commerce—finally is dammed up and derailed. As that FT piece on container ships is right to note, the trouble with trade wars is that they “have a habit of escalating as recipients slap on tariffs of their own,” and that’s why we have a global trading system to begin with—to restrain the worst, most self-destructive impulses of governments of the type we last saw during the Smoot-Hawley era. My bet is that we avoid the worst-case scenarios here and abroad, but it’ll probably be a costly, messy, annoying ride nonetheless. And, of course, it’s a risk we should’ve never had to deal with in the first place.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.